Finders Keepers

| June 3, 2025Nathan Raab scours the world for lost pieces of history — and sells to the highest bidder

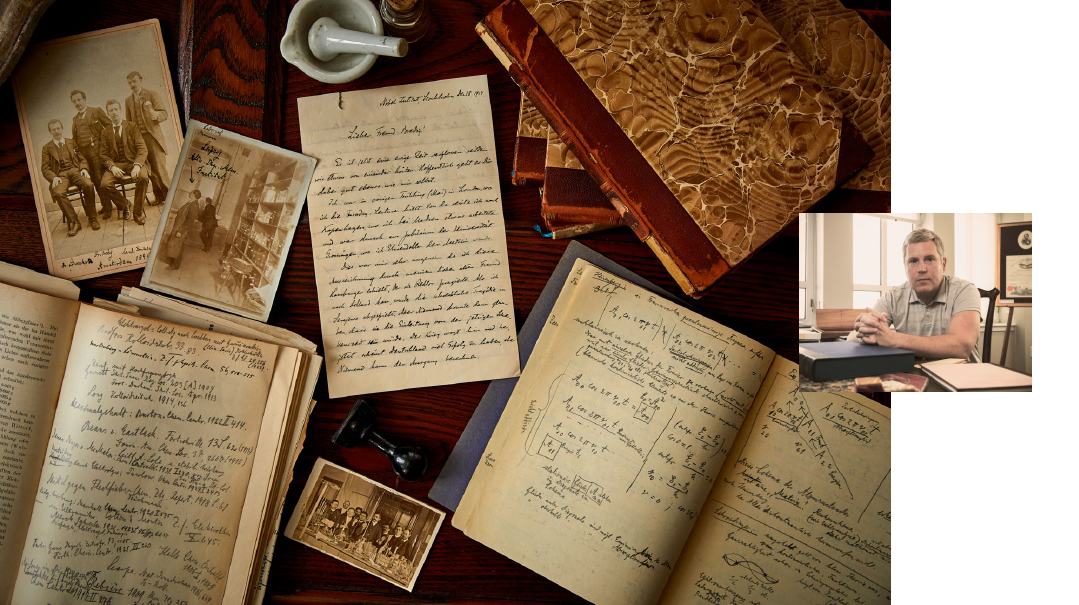

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian, Raab Collection

The Raab Collection, one of the world’s leading sellers of historic documents, is really a hidden treasure trove, built upon the scavenging of auction catalogues and private home closeouts in search of gems long neglected, undervalued, or overlooked. “You go to this guy’s house and find hundreds of documents that no one’s seen for two centuries,” says president Nathan Raab. “We scour the world looking for these lost pieces of history”

One day, Nathan Raab, a prominent dealer in rare historical documents, got a call about two letters up for sale written by Albert Einstein.

The letters, in which the famed scientist discussed his signature theory of relativity while it was yet in its early stages, were written to a German-Jewish scientist named Georg Bredig, who was considered one of the leading experts in the field of physical chemistry. Bredig worked with leading scientists of the day including Max Planck, Einstein, and some other early Nobel Prize recipients.

It was Bredig’s grandson and namesake who made the call to Nathan Raab, president of the Raab Collection, a firm that specializes in the acquisition and sale of significant historical manuscripts. After checking the letters’ authenticity, Raab made a tentative offer, inviting grandson George Bredig to his home in suburban Philadelphia. Only one letter was sold at that meeting, but before he left, George told Mr. Raab, “There’s a lot more at our house. You should come see it.”

A few months later, George called to negotiate sale of the second Einstein letter and repeated his invitation. Since the transaction yielded two very valuable finds, Mr. Raab and his father Steven — founder of the Raab Collection — decided to take him up on the offer, so they traveled to Bredig’s home in rural Tennessee, thinking that there might be a few more documents worth purchasing.

When the Raabs descended to the basement to check what else there was to see, they realized that George Bredig was right. The basement was lined wall to wall with books, letters, photos, and notes that had once been in the elder Bredig’s library.

Both Nathan and Steven Raab began to make their way through the copious shelves and boxes, feeling as if they were diving into a time warp to a golden age of knowledge and advancement. There were endless notes, letters, and books detailing the evolution of physical chemistry through the early 20th century, organized by decades.

Then, as the Raabs’ investigation took them into the 1930s, the skies over Georg Bredig quickly dimmed.

Opening boxes labeled “immigration” and “visa” took the Raabs down a path that told the agonizing story of Bredig’s suffering during the Nazi years and his eventual escape.

“There was a lot of triumph and tragedy that had never been told,” Nathan Raab told Mishpacha. “Going through these original documents was like reading a book.”

A few weeks after that encounter, George Bredig drove 25 banker’s boxes to Raabs’ offices. Reading, translating, and organizing the collection took the Raabs close to a month, during which Bredig’s saga continued to unfold.

“We started out looking at two Einstein letters, but the depth of this entire archive was just monumental,” Nathan Raab says.

Oops! We could not locate your form.