Fight to the Finish

“My world changed entirely during that war. Nothing was ever the same again and the memories never fade”

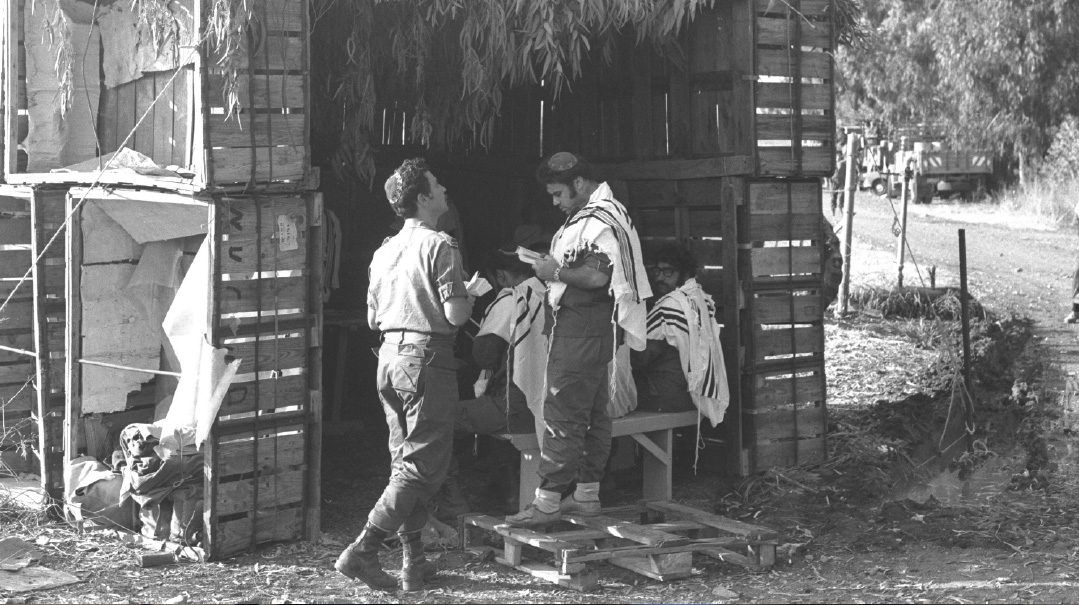

Photos: Yossi Schwab

Fifty years ago, Rabbi Chaim Sabato was a 22-year-old yeshivah bochur dragged out of shul to help fend off the enemy. Today, as a prolific author and a rosh yeshivah of the hesder yeshivah in Maaleh Adumim, he reflects back on that unforgettable Yom Kippur, on his best friend who was assigned a different tank and then killed, but mostly on the outpouring of chesed with so much love and sacrifice for one another. “When I saw all that unconditional giving even under fire,” he says, “I knew we’d win”

He’s known as a prolific writer of inspirational books, and a voice of insight, courage and emunah when it comes to the battle annals of the Yom Kippur War. His book, Ti’um Kavanot (Adjusting Sights, in English), the moving account of a soldier in the Yom Kippur War, is based on his own experiences as a yeshivah bochur-soldier navigating an impossible battlefield.

But Rabbi Chaim Sabato is more than a highly acclaimed author (his titles include Aleppo Tales, The Dawning of the Day: A Jerusalem Tale, From the Four Winds, and Rest for the Dove). He’s also the founder of Yeshivat Birkat Moshe, the hesder yeshivah in Maaleh Adumim, where he’s served as a rosh yeshivah for over 40 years.

Fifty years after he came back from the battlefield on the Golan Heights, the war that molded the rest of his life still reverberates.

“My world changed entirely during that war,” he says. “Nothing was ever the same again and the memories never fade.

“It wasn’t only a war of mortars and tanks,” he says. “We religious soldiers had our tefillin bags at our sides, and we recited Tehillim whenever there was a lull. But there was also another spirit, not just the tefillos of the religious soldiers, but the noble actions of the soldiers I saw around me, who risked their lives for Am Yisrael, carrying out unbelievable heroic acts out of love and friendship for their comrades, and all under impossible conditions, amid the hail of artillery fire and constant shooting.”

Y

om Kippur afternoon 5734/1973. Chaim Sabato, a 22-year-old student at Yeshivat Hakotel, was davening Minchah at his family’s shul in Jerusalem’s Kiryat Hayovel neighborhood. While most of his friends remained in yeshivah, Chaim’s father was the longtime gabbai and chazzan in the Kiryat Hayovel shul, and Chaim and his three brothers didn’t want to miss a tefillah with their father.

“Just then,” Rabbi Sabato remembers, “we heard sirens outside. The rav of the shul banged on the bimah and announced, ‘They say there’s a war, we must pray.’ Because I was serving at the time on the Yiftach Base near Rosh Pina, not far from the Golan Heights, I knew we would be among the first brigades that would have to go into combat against Syria, so I didn’t even wait for them to call me up — I just ran home.”

Chaim Sabato received his official call-up notice a short time later. It was already nighttime by the time he reached the pickup point, and on the way, he and his friend Dov Indig ran into a group of Amshinover chassidim who were gathered for Kiddush Levanah outside their shtibel, which was up the street. They still hadn’t broken their fast.

“Someone pushed Indige and me into the circle of chassidim surrounding the Amshinover Rebbe ztz”l, and the Rebbe [Rav Yerachmiel Yehudah Meir Kalish, who passed away in 1976 and was succeeded by his grandson, the current Rebbe] gave us the brachah ‘Tipol aleihem eimasah va’fachad,’ that ‘Fear should be cast upon them, not you.’ For three days, that sentence echoed in my ears, until I heard that Dov — my closest friend — had fallen in battle.”

D

uring those initial days, the Rebbe’s brachah infused young Chaim with hope and confidence in what would be a clearly precarious situation.

“As soon as we got off the bus at our assembly point at a base near a kibbutz in the Jordan Valley, the atmosphere changed drastically,” he relates. “It was pitch-black and we couldn’t see a thing. Someone turned on the communications device to the frequency of our brigade, 188, and suddenly we heard screaming all around us: ‘I’m being shot at!’ ‘The tank is burned!’ ‘We’re finished! We have to retreat!’ and other blood-curdling cries.

“After our unit got a bit more accustomed to the darkness, we saw the tanks that were waiting for us. We grabbed whatever ammunition we could from the storage room — a pistol, binoculars, a machine gun —and loaded it into the tank. Amid the chaos, the senior commanders walked among the tanks and ordered, ‘Any tank that’s ready should move out. If not, we’re going to lose the Golan.’

“My tank’s commander was a fellow named Dov Pasternak, who’d come from the US to join the IDF. In the next tank were other members of the yeshivah, including Rabbi Shmuel Holland and Shaya Holtz, both of whom were killed the next day. Natan Graz was also with them, and he was seriously injured.

“A few minutes before we set out, Shaya Holtz climbed up onto our tank and informed us, ‘Chevreh, there’s a serious war going on here, we need to pray.’ We all stopped and recited some Tehillim — except for Pasternak, our commander, who claimed that he was an atheist. Later, though, we saw what exemplary morals he lived by.

“The unique composition of our unit, which included so many bnei yeshivah and talmidei chachamim, influenced our deliberations. For example, before we departed, we had to eat something — we hadn’t even broken our fast. The kibbutz members threw apples into the tanks for us. We were all very hungry, but Rabbi Shmuel Holland, who would be killed just a few hours later, noted that as we’d just come out of the shemittah year and these fruits were likely cultivated in a forbidden manner, it was possible that, according to certain halachic opinions, we weren’t allowed to eat them. A major discussion ensued between our tanks over the communication radios, just as our tanks headed out to a war closer than we could have ever imagined.”

T

he tanks reached an area near the Jordan River that had already been captured by the Syrians.

“As soon as we arrived, we saw an Israeli fighter plane shot out of the sky right in front of our eyes,” Rabbi Sabato remembers. “We were shocked, because we were still under the shadow of the heady victory of the Six Day War and were very confident that it would happen once again now.

“I remember that as we advanced, we kept coming across injured soldiers who were waiting to be rescued, and I remember someone from our unit finding his own brother in very serious condition.

“We got moving the next day at four in the morning, but it turned out that the Syrians had preceded us, and were bombarding on all sides,” Rabbi Sabato recalls. “We split up into two groups, one went down into the wadi, while we stayed on the slopes of Har Shifon, as we needed to provide cover and strike at enemy tanks. At this point, the force in the wadi began to sustain fire. We were right across from them, but the sun blinded us and we could hardly see anything. We just heard the screaming on our radios, which reported which tanks had been struck. We knew who was in each tank — these were all our friends.”

Rabbi Sabato says that at in those minutes, he focused solely on aiming the shells and trying to be as precise as possible. “I didn’t feel any fear, I didn’t think about anything, only about how to strike the tank that was riding opposite me,” he recalls. “It was an endless assault, the Syrians were firing and hitting us, and we were striking back. We didn’t give up, but the situation was dire, and of dozens of tanks, only a few made it through.

“Then it was our turn to be hit. Suddenly we noticed a Syrian tank bypassing us from behind and pulling up alongside us. Dov Pasternak shouted at me, ‘Sabato, fire!’ and I looked and saw that the tank was just 300 meters from us. We didn’t even need to look through the periscope. We saw it all from the window. Dov continued shouting, ‘Fire, pray!’ and I answered him, ‘Fire, you pray!’ and he shouted, ‘I don’t know how to pray!’ and I answered him, ‘So we’ll pray together!’

“We both screamed, ‘Ana Hashem hoshia na,’ and the shell made a direct hit. The Syrian tank was damaged, but we heard a huge noise and we realized that a shell had hit our line as well. We hurriedly clambered out of the tank, but then Dov signaled to us to his ears and motioned that he didn’t hear a thing. A piece of shrapnel had hit his helmet and penetrated his ear, which made him lose his hearing.

“We tried to get out of there, because the greatest danger is to stay in a damaged tank — it’s like a sitting duck, the easiest target to strike. But then I noticed that Ronny had not come out of the driver’s compartment.

“I ran back to the tank, and under fire, I climbed up to rescue him, and shouted, ‘Ronny, get out!’ And he answered, ‘I can’t get out, it’s all blocked!’ I tried to move the twisted metal and debris aside, but it was useless. I tried harder, but couldn’t do it. And all this was under enemy fire. Then I remembered the hammer I’d grabbed from the storage room before we’d left. I began to strike with all my might, but the blockage was not budging.

“After a few minutes and more hammering, it finally broke loose. Ronny was able to get out and we were all outside with Dov, our tank commander, who motioned to us again that he couldn’t hear. We half ran, half crawled along a few hundred meters, until we came to a trench. We considered taking cover inside it but a passing soldier motioned to us not to take cover, but to keep running. It turned out that he saved our lives, because soldiers who took cover in that trench were killed.

“We kept advancing. It was very hard for Dov to walk because of his injury, so we supported him. At one point we reached an open road and realized we couldn’t go forward from there, so we sat and waited. We were in Syrian territory and completely exposed to the enemy, waiting for a rescue that may or may not come.

“Suddenly, we noticed an Israeli car approaching, and hoped that this could be our salvation. We waved, but the driver didn’t notice us and kept driving. And then, a horrific scene unfolded before our eyes: There was Syrian fire in the distance, and a soldier suddenly leaped out of a burning tank, all aflame himself. He fell onto the ground and rolled over a few times, then spilled a whole jerrycan of water on himself to douse the flames. The driver of the private vehicle turned out to be a civilian who came to help as a volunteer. He evacuated the injured soldier and saved his life. We stayed there and continued waiting. We davened Minchah and said Tehillim.”

D

uring those hours, the lives of Rabbi Sabato and his friends hung by a thread.

“Some fighters transferred to different tanks after their own tanks burned up. But we had nowhere to go,” he says, “because we were the last in the convoy. We were completely exposed to the enemy.”

Plus, their commander was injured and had fallen asleep. But at around five in the afternoon, he roused himself and took command: “We’re going back to the tank and try to fix it.” And so, the troops turned around and began making their way back, four soldiers with one Uzi, without even a strap.

Suddenly, Rabbi Sabato remembered: It was almost shkiah and he hadn’t put on tefillin yet.

“From the day of my bar mitzvah, not only had I never missed a day of laying tefillin, I’d also gotten a special brachah from Rav Salman Chugi Aboudi ztz”l, the last rav of Baghdad who lived near us in Kiryat Hayovel. He blessed me on the day of my bar mitzvah that I should merit to put on tefillin every day of my life.

“I ran to the tank, rummaged around inside and took my tefillin, putting them on as fast as I could while Eisenthal screamed to me, ‘The sun set already, you can’t make the brachah!’ And I answered, ‘The sun didn’t set yet!’ With siyata d’Shmaya I merited to put on tefillin every day of the war, and to this day, I have a running argument with Rav Eisenthal if the sun had already set or not.

“After a few days of war, Shabbos came,” Rabbi Sabato recalls. “It could have been like a regular weekday, because we were still fighting and eating the same battle rations. Nothing was really different. But I wanted to feel Shabbos a bit more, and when I checked my kit, I found my military belt. So I decided I would wear this belt in honor of Shabbos, and that would be my oneg Shabbos. And unbelievably, 30 years later, I was giving a lecture in one of the towns in the Golan, when the council head came to me he said, ‘You should just know that I’m shomer Shabbos because of your belt.’”

Rabbi Sabato holds on to an unforgettable memory from that Succos: Adir Zik a”h, who served in the artillery corps and later became a journalist, found a dugout that was ten tefachim high, brought branches and put on sechach, and that’s how they had a kosher succah.

“There was not a soldier in the area who didn’t visit our succah,” Rabbi Sabato says. “We were even able to have arba minim, because one of the soldiers had a minhag from his father that he didn’t leave the house from Rosh Hashanah and on without a lulav and esrog. He had gone out to war with the daled minim and that’s how we were able to do the mitzvah..”

Throughout those fraught days, Rabbi Sabbato says, there was so much dedication and bravery, with so much love and sacrifice for one another. “If a tank got stuck, everyone around joined in to help free it, even if they were under fire. I remember an officer who was wounded in the shoulder, yet he continued shooting at an advancing Syrian, in order to save his friend.

“Today,” he continues, “we’re being told that our society is fractured, but I want to tell you what it was like in the trenches: There were secular officers who fought like lions to save the lives of the frum fighters in our brigade, because there was a tremendous sense of unity, even if many of us didn’t know why we were in this war, why we got off to such a bad, bloody start, or what kind of decisions the upper military echelons were making with our lives.

“On Shabbat, when we made Kiddush in the tank, they all came to listen, and later, when we built a mehudar succah, they all wanted to come in. There was this atmosphere of camaraderie, unity and emunah, and I believe that that was our greatest advantage.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.