Field Doctor

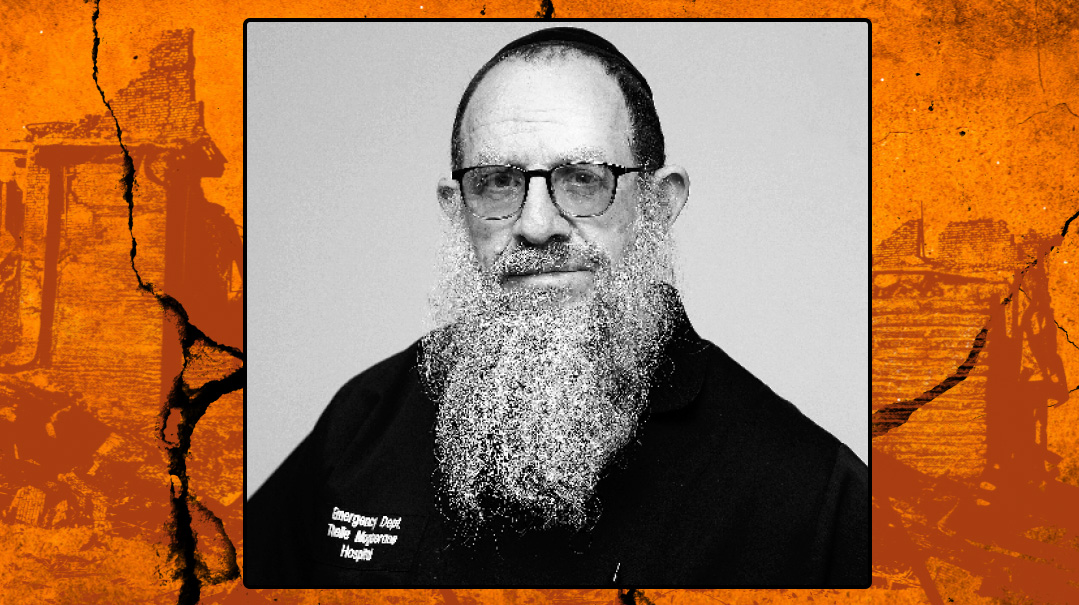

When FIFA hired disaster doc Professor Efraim Kramer

Photos: Ilan Ossendryver, Personal archives

People who were curious about the fellow with the black yarmulke, mingling with the VIPs on the soccer field during the summer that Russia hosted the World Cup, would be excused if they thought he was a Chabad rabbi from Moscow or a baal teshuvah Russian oligarch.

In fact, the mysterious kippah-clad fellow conferring with the heads of FIFA was none other than a frum South African doctor, considered the world’s expert on both disaster and sports medicine.

Professor Efraim Kramer is the retired head of Emergency Medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and professor of Sport Medicine at Pretoria University. In 2018, he was appointed Chief Medical Officer of the FIFA World Cup — but that was really just the culmination of 35 years in the trenches as a mass casualty/disaster medicine authority, having directed international rescue teams in earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, floods, and volcanic eruptions. And while he’s traveled to 78 different countries and has served on the medical team at seven World Cups, the place he’s truly at home is the Johannesburg Kollel, where he spends his mornings learning Torah.

In a way, it’s coming back to his roots.

In the early part of the 20th century, Lithuanian Jewry began to emigrate by the thousands to more hospitable environs (and not just politically, but a place that was warmer and sunnier than the freezing, dark north). Among those hordes were the Kramers. Efraim’s grandfather was a talmid of the Slabodka yeshivah and his father of the yeshivah in Shavel. Like the great waves of immigrants to America at the turn of the century, for these newcomers faced with adjustment and the rigors of finding a livelihood, religion fell to the wayside.

The Kramers ended up in Welkom in the Orange Free State in central South Africa. To portray how removed Welkom is from the South Africa people identify primarily as Johannesburg and Cape Town, the closest towns are Odendaalsrus, Kroonstad, Phuthaditjhaba, Bultfontein, Bloemfontein (the provincial capital), and Potchefstroom. There were about 100 Jewish families in Welkom, all of them secular Litvaks.

“My upbringing in Welkom,” says Professor Kramer, “was completely secular, to the extent that I learned my bar mitzvah parshah on a tape recorder and then regurgitated it at the said time on a Shabbos.”

Once Efraim finished high school, his father asked him about his future plans. He answered with nothing more loquacious than shrugged shoulders, for he hadn’t really given it too much thought. In Welkom, where the dominant language was Sotho and the major employment was mining, gainful employment was not a subject that merited a lot of attention.

Efraim’s father, though, had a bigger agenda for his son, proposing the possibility of a medical career. And so, without much thought concerning his own future, Efraim applied to University of the Witwatersrand, which had a few open spots for English-speaking medical students from the Orange Free State.

Surprising even himself, Efraim finished all of his medical training, but soon after was conscripted into the South African Army and placed at the Military Aeromedical Institute. He was assigned to helicopter aeromedical evacuations and a spark suddenly ignited. Efraim Kramer was now engaged in high-octane exploits that made emergency room work seem as mild as milk.

Treating a stationary patient on a bed on the ground can be stressful even at a fully staffed hospital. Compare that to the belly of a helicopter, with insufficient light, limited space, and vibrating from turbulence, altitude fluctuations, and maybe even enemy gunfire.

“This kind of work,” says Professor Kramer, looking back, “made me an emergency medical adrenaline junkie for good.”

“One cannot even fathom the challenge of treating badly injured patients in the absence of a hospital.” Dr. Kramer started out in overcrowded emergency rooms, but he was soon on the site of natural disasters and medical catastrophes

From aeromedical evacuations, it was a natural progression to emergency medicine, eventually leading to specialization in medical oversight of disasters and mass gatherings. Professor Kramer’s résumé reads like a list of “Head of Emergency This” or “Former Head of Emergency That,” along with being cofounder and medical director of Rescue South Africa, which brings medical teams to natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes, hurricanes, and floods. When a natural disaster strikes (think Hurricane Katrina), the lives of thousands will be dependent upon the implementation of an efficient triage system. When tens of thousands of people gather, if something goes awry, the chance of it metastasizing with everyone pressed together spikes. Preventing catastrophes, and coping with them if they occur, is Professor Kramer’s expertise. His studying disaster management was never meant to be academic though, and in short order he was out in the field saving lives and stemming catastrophes.

He’s been doing this for so many years that, when speaking with Professor Kramer about his line of work, he comes across with a calmness that might sound callous or indifferent. But that’s because he learned early on that he must maintain his calm and coolheadedness in order to execute the most efficient relief. If witnessing disasters and observing carnage bothers Efraim Kramer, he hides it well.

“The first major international disaster I was involved in,” he relates, “was the Mamara earthquake in Turkey in 1999. Thousands died in their sleep and buildings collapsed everywhere. I co-lead a team of rescue and medical colleagues to assist in victim evacuations. We returned home and formed an NGO, Rescue South Africa (RSA), a disaster response team that has since rushed to assist disasters worldwide.”

If you’re speaking with Professor Kramer, he’s likely to be interrupted by a phone call from the Thelle Mogoerane Regional Hospital where he is an emergency department specialist. This is a government hospital where there aren’t enough facilities or medical apparatuses to deal with the onslaught of patients. Decisions have to be made every hour concerning newly-admitted patients riddled with bullets, deep knife wounds, fire victims (all common in South Africa), and Professor Kramer will unspool instructions to “amputate,” “unplug,” “intubate,” with the unflinching factual intimacy of a coroner’s report. (Color me astounded, for if I catch a fleeting glimpse of minor surgery at a bris I am ready to faint. Professor Kramer cannot allow himself these puerile responses or it will throw him off his game.)

When you’re in Haiti winding your way through rubble of a collapsed nursery, hunting for trapped children, you must be single-minded. There are thousands of corpses piled on the streets, with not an inch of room in the overwhelmed morgues. In the heat and humidity, the bodies are decomposing and their acrid odor could put a gorilla out of business. “We were treating injured babies,” and here his voice darkened an octave, “without a clue where their parents were, or if they were even still alive.

“One cannot even fathom,” Professor Kramer added in a tone devoid of self-pity, “the challenge of treating badly injured patients in the Philippines in the absence of a hospital that was ravaged in 350 kilometer-an-hour winds.”

In 2000, Professor Kramer led his team to Mozambique, which was inundated with flooding, resulting in sharp increases in malaria and diarrhea. The water supply was also disrupted, ravaging nearly half a million displaced or homeless, including 46,000 children under age five. But there was other fallout as well: Mozambique was riddled with landmines — close to 200,000 of them — left after a fight for independence and an ensuing civil war in the 1990s. Due to the flooding, Professor Kramer saw, to his horror, landmines everywhere, having risen from the water-saturated ground. They were precariously balancing on tree branches, on windowsills and on top of cars, haphazardly deposited by the rising flood waters.

No one said rescue work would be easy — or safe — but the mantra that guides Professor Kramer and his colleagues on these humanitarian operations is, “You do what you have to do.” That means that when on such a mission, your own personal safety and security is not paramount. A less committed individual probably wouldn’t have rushed to provide medical relief following the Japanese earthquake and tsunami in 2011, which brought in its wake the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear power plant. There was leaking radiation, but that didn’t stop Professor Kramer and his team from being there.

Professor Efraim Kramer, the bearded, black yarmulke-clad fellow on the World Cup soccer field. He prefers to spend his days studying in Johannesburg’s kollel, but after 35 years as a mass casualty/disaster medicine authority, FIFA drafted him as its Chief Medical Officer

But what happens when disaster strikes in the middle of a war zone? “War-torn” is a permanent adjective for the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), but when Mount Nyiragongo erupted, it didn’t seem to take into consideration that there was a civil war going on. Lava poured out — avalanches of searing ash and rock releasing carbon dioxide, methane,, and other toxic gases resulting in explosions, earthquakes, and asphyxiation — its hot stream traveling all the way to Goma, the capital of Congo’s North Kivu province.

Whoever coined the expression “getting there is half the fun” never traveled to Goma in the middle of a civil war. The relief crew could not land in Goma (whose runway was one third under lava) nor in the capital of Kinshasa, as the area was under siege by the rebels. The only way in was to land in neighboring Rwanda and then form a truck convoy to transport the medical and humanitarian supplies. The drive from Kigali, Rwanda to Goma, DRC was a 250-kilometer excursion through mountain ranges in the midst of rebel-controlled territory.

There were no communication channels with the rebels and their reaction to anything that they were not familiar with was to shoot. This presented a rather challenging dilemma to Team Kramer. They could either travel by day, where their convoy would be an easy target for the rebel gunners, or negotiate the narrow mountain passes at night without headlights. The lethal odds were about the same.

The doctors opted for the latter, turning on the headlights for a split second and then driving for 100 meters in opaque black, hoping that the truck in front and behind them estimated 100 meters the same way.

Miraculously they made it. But that didn’t mean that they had averted the scrutiny of the insurgents. The rebels did not take kindly to uninvited guests. In their thin list of assets, hospitality was not one of them.

In the morning, Professor Kramer and a colleague were separated from the group and brought to the rebel leader, who would decide if the intruders should live or die. The posse was composed of a bunch of thugs with rows of bullets wrapped around their chests.

The two doctors were thrown into a room in rebel headquarters after traversing a row of never-ending doors. There they waited for the pronouncement of their verdict. They waited and waited as a rag-tag army of hooligans, some dressed, some barely, some with shoes, some without, some with hats, some with towering helmets of black kinky hair, peered down upon them.

And then the door flung open and a powerful man, shaped like a tall fire hydrant wearing only teal-green shorts, strutted in. Everyone froze in fear. Kramer rose, and without any inhibition went over to the leader and punched him in the chest.

A roar of astonished silence gripped the room as every soldier cocked his gun and placed Professor Kramer directly in their cross hairs. The rebel leader erupted into an industrial smile revealing crooked and overlapping teeth, while the motley group of fighters looked at each other gape-jawed, as Kramer delivered yet a second punch with his other fist.

“You creep,” he admonished, “next time you decide to leave my hospital and start a revolution, you had better tell me first!” The two of them locked in a bear hug, as Kramer’s hyperventilating, chalky colleague resumed normal breathing.

It turns out that the rebel leader was a doctor who had come as a refugee to South Africa and worked in the trauma unit that Professor Kramer directed. One day he just disappeared. Needless to say, Professor Kramer’s execution was stayed, and his team of volunteers were allowed to do their lifesaving work.

Teaching football emergency medicine in Kigali, Rwanda. Disaster medicine is his specialty, but emergency sports medicine is his passion

Meanwhile, Professor Kramer was going through a bit of a revolution of his own.

“When I came to Johannesburg to attend the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), I was completely secular and illiterate in Hebrew,” he admits. “But one Yom Kippur day while I was relaxing at home — a free work Jewish holiday — my wife came back from the Chabad shul she attended and said that the rabbi asked that I come to shul for just five minutes. Well, being slightly bored doing nothing at home, I acquiesced and went to the Chabad shul where I met Rabbi Alex Carlebach. Well, I never did stay for five minutes — I remained until the end of Ne’ilah and had a fire ignited within me that day that has been burning ever since.”

Professor Kramer and his family — he has three daughters — remained at Chabad for a number of years until they moved to be closer to the religious schools the girls were attending. At that time, Professor Kramer was active in prehospital emergency medicine, emergency medical ambulance services care, and paramedic education and training.

“It was therefore vital that when we moved, the shul would be close by so that if I was summoned for a medical emergency, I could run home on Shabbos to my emergency response vehicle,” he says, “and that’s how I became a member of the Yeshiva Maharsha campus, comprising a nursery school, primary and secondary girls’ and boys’ schools, shul complex, mikveh, and other amenities, with the Rabbi Menachem Raff as mara d’asra, who over the last 30 years has become my teacher, my mentor, and my life guide and Torah role model.”

With the religious fire ignited within, Professor Kramer — self-admitted nonconformist that he is — is grateful that he was given the opportunity on the one hand to be at the forefront of the development of emergency medicine both inside the hospital emergency department and in responding internationally to the world’s disasters, while on the other hand, to be under Rabbi Raff’s tutorage, and, as he says, “to grow day by day in Torah, book by book, page by page.”

Inspecting ambulances in Moscow. The high-profile Orthodox doctor soon became a source of pride for a people rarely given an opportunity to acknowledge their religion in public

Because of Professor Kramer’s extensive background in emergency medicine, sports medicine, and oversight of disasters and mass gatherings, he was a natural candidate to assist with the preparations for the World Cup — the largest sporting showpiece on the planet — held in South Africa in 2010. The event would become a defining moment for South Africa, for neither the Olympics nor the World Cup had ever come to the forgotten continent, always conjured as the venue of war, disease and famine.

Finally, there was a chance to show the world a different face. And yet, there were a host of issues that could go wrong, from infrastructure to transportation to the construction of Soccer City (that would hold 100,000) and 11 stadiums, the largest one holding 85,000 fans, and the thorniest of all — medical care.

Professor Kramer’s previous medical management of major events such as pop concerts or the Cape Town Marathon, with 18,000 runners and tens of thousands of spectators, would pale next to the World Cup, which entails supervising millions of people for over five weeks. Still, because of Professor Kramer’s résumé and experience, he was the ideal choice for FIFA (“Fédération Internationale de Football Association,” the international governing body of the World Football Association) to oversee the tournament. Yet, would the modest, kippah-clad, bearded, half-day learner wish to be FIFA’s World Cup medical manager? Many of the matches occur on Friday night and Shabbos, so the first thing he needed to do was to ask his rabbi. The FIFA administrator responded incredulously, “We want you, not your rabbi.”

Professor Kramer, always attuned to the call of duty, was nevertheless confident that his rabbi would nix the proposal. But sagacious and perceptive Rabbi Menachem Raff did not live up to the expectation. He asked if there would be Jews in the stadium, and when Professor Kramer answered in the affirmative, Rabbi Raff ruled that he should accept the offer (conditional upon working with a Shabbos goy and undergoing intensive halachic instruction for the specific issues that would come up).

Professor Kramer rose in the ranks from being the regional director of the 2010 World Cup to FIFA’s chief medical officer in 2014, when the World Cup was held in Brazil.

Months before the actual kickoff, Professor Kramer and his team would be preparing. He would personally inspect the hospitals in every city where there was a stadium (32 teams participate in the tournament, entailing the use of numerous stadiums), review the ambulance services, and verify that the necessary medical equipment was present. Professor Kramer even wrote a first-ever innovative manual regarding how to prepare for and conduct medical procedures at soccer matches (there’s no way to estimate how many injuries and deaths have been prevented through this manual). Professor Kramer’s word was law; the manual was the bible and the slightest nonconformance meant that FIFA would not authorize the soccer match — which would mean goodbye prestige and local economy surge.

A stadium holding upward of 45,000 people (jumping up and down) is the population of an entire town, and as such, someone there is likely going to trip and fall, have chest pains, have an asthmatic attack… and maybe have a baby. Furthermore, fans attending such an event — even if they feel sick or faint — are not going to want to leave. Regarding the players themselves, FIFA instituted anti-doping guidelines, in which all players are required to undergo doping controls through urine and blood samples to ensure there is no cheating by means of prohibited substances and performance-enhancing drugs.

The soccer teams are equipped with their own sport physicians, and the presidents, prime ministers, sheikhs, and other VIPs who attend are often accompanied by cardiologists or a range of other specialists who escort these notables. Responsible for all of them is FIFA’s Chief Medical Officer.

With advancing age, Professor Kramer has decided to wind down some of his medical adventures. While he’s still an emergency medicine consultant and teacher and mentor to both students and doctors, he’s found extra hours to increase his commitment to Torah learning

The third match of the Brazilian World Cup was in Manaus on the Amazon River, in the center of the world’s largest rainforest. From a medical vantage point, Professor Kramer’s team was on high alert to prevent or treat heat stroke. From a personal one, staying in a hotel over Shabbos was not an option because of the distance to the stadium.

Professor Kramer resolved that he would spend Shabbos in the medical room in the stadium. When he apprised his local colleague of his decision the man fretted, “How in the world will you manage? The place will be dark and there will be no air conditioning — and remember, this is a malaria region!”

Professor Kramer calmly replied, “I’m from Africa, I can manage.” Oddly, the solitude was actually invigorating, and he savored shouting Kabbalas Shabbos from the depths of the Amazon. Kramer didn’t leave the room all Shabbos, and mysteriously, the light and the air conditioning never went off.

After Shabbos, Professor Kramer found out that the local medical representative was so concerned about the poor Jewish doctor that he appealed to the stadium’s engineer to jerry-rig a solution. The engineer came up with a work around, but it is doubtful if Accounting would have approved. He left the lights and air conditioning on for the entire stadium.

The obvious problem with travel all over the world — and he’s been to 78 countries in total — was kosher food. But no matter what the challenge, FIFA had the connections and the clout to coordinate. There are 250 million high-level soccer players in the world, 40 million are women, and 40 million are between the ages of five and 15. All of them are connected to clubs and leagues, and ultimately to FIFA. There are more countries in FIFA than there are in the UN.

In 2015, Professor Kramer was in charge of the Under-20s Women’s World Cup in Papua New Guinea, in the southwestern Pacific. Professor Kramer wrote the organizers in advance requesting kosher food, which didn’t exist in Papua or its environs. For an organization that knows how to host 3.4 million people, arranging kosher meals was a really minor challenge. FIFA flew in meals from Adelaide, Australia, 2,000 miles away.

FIFA hosted an African conference match in Casablanca, Morrocco, in 2019. Although the game was Saturday night, the doping checks and other pregame preparations had to be performed before the conclusion of Shabbos. Once again this ruled out the option of staying in a hotel, so the medical room it was. But there was one catch: The king of Morocco was going to attend the match and therefore security would be at a maximum, with the premises sanitized before the game.

Professor Kramer was not anticipating such an uneventful Shabbos, and was curious as to why the security dogs had not sniffed him out. How should he have known that a security guard had been stationed outside the room?

IN 2017, after experiencing bouts of abdominal discomfort, Professor Kramer became a patient in his own emergency department. After the medical team discovered two tumors intra-abdominally, which were suspected of being malignant, he underwent a complex surgical procedure for removal of the main, grapefruit-sized mass, with the second tumor inside the liver left for another time (it was later discovered to be benign). The excised mass turned out to be a rare malignant tumor, which invaded locally but did not spread, and so having had it completely removed meant he was essentially cured of the malignancy.

“Today, six years later, I remain thankfully, baruch Hashem, alive and well, so although I’m not getting younger, I see this stage of my life as my second chance,” he says, giving himself an additional challenge. “That means I’ve been taking my Torah learning and commitment to ever increasing levels of understanding and determination as the increments of ‘clean’ time continue to pass, day by day, month by month, and year by year.”

And so, with a clean bill of health after a dreadful scare, it was on to the World Cup of 2018, which was held in Russia. Selecting this particular host country was controversial because of the preponderance of concerns regarding issues that were not FIFA-friendly. Russian football, for example, was rife with racism, and the country at large was plagued with human rights abuses and discrimination. The annexation of Crimea was a sore spot, as was the charge that North Korean forced labor (in lieu of that country’s payback to Russia) was made to work in dangerously cold conditions building stadiums without pay, and at least 17 workers had reportedly died on World Cup construction sites.

Before and during the World Cup, FIFA practically takes over the host country. A full year before the World Cup, Professor Kramer began his preparatory tour to inspect Russian stadiums and hospitals, and probe how equipped they were to deal with medical disasters. He toured 12 stadiums located in different Russian states, each of which had its own minister of health who met with Professor Kramer amid gala and pomp featured daily in every media outlet. Overnight this Orthodox Jewish doctor became an icon throughout the country, and a source of pride for a people rarely given the opportunity to acknowledge their religion in such a public venue.

In Russia, FIFA didn’t need to concern itself with kosher food. Even the far-flung Jewish communities graciously volunteered their help for the famous religious doctor.

When Professor Kramer traveled to Rostov-on-Don (in southern Russia, adjacent to the Sea of Azov), waiting at the train station in freezing weather was Rostov’s medical delegation. As they were shaking hands and smiling for the photo ops, off on the side was the gabbai of Rostov’s shul, armed with plentiful food provisions.

This happened wherever he traveled, and each community outdid the next to accommodate and make him feel welcome. In Volgograd (former Stalingrad), the Chabad rebbetzin had prepared a meal for him with four desserts. Professor Kramer called her up to thank her and inquired as to why she had made four? She answered innocently, “I didn’t know which one you would prefer.”

Professor Kramer received an email from the rabbi in faraway Sochi, along the Black Sea, asking if he could pay him a visit when he came to town. Professor Kramer, who was working on FIFA’s clock, arrived in the morning, toured the local medical facilities, and was out by the evening. Nonetheless, never wanting to turn a fellow Jew away, when everyone else was having lunch in Sochi Hospital Number Two (the Russians aren’t especially known for imaginative names), Professor Kramer absconded to pay a visit to the town’s Chabad rabbi.

Awaiting him was an elaborate banquet, but this was not why he was summoned. “There are half a million Jews in Russia,” the rabbi began with an urgency in his voice, “but in this town, my access to them is primarily when they’re about to die, or if a relative has passed away. All their lives they were content to live as non-Jews, but at the end, they want to be buried in a Jewish cemetery. Most of them, especially the older ones, are afraid to do anything Jewish because they still fear the old regime, and as soon as I bury their loved one, they vanish as if the KGB were still on their tail.

“And now, all of a sudden, FIFA elected to stage the World Cup in Russia, and everywhere we turn we see a bearded man with a yarmulke meeting all of the important people. These people have never seen such an openly visible Jew in Russia before. I needed to bring you here to show you what you’ve done and how, without even realizing it, you’ve changed the religious climate here. We’ve decided that in every shul in Russia this week the derashah will be about your example, that one need not be scared to show he’s a Jew.”

While the World Cup officially began in June 2018, the preceding February Professor Kramer scheduled a conference for all of the medical teams in each of the stadiums so that he could brief them on doping checks and all other medical matters.

For Efraim Kramer, it was coming full circle. His parents had fled Russia decades before, and now he returned business class and was driven by a chauffeur to a luxurious hotel overlooking the Moscow River. As Professor Kramer approached the conference welcome desk, one woman asked excitedly, “Is that a kippah on your head?” When he answered in the affirmative, she practically shouted that she was also Jewish. Another woman at the conference asked if he knew where she could hear the Megillah, as Purim was approaching. Professor Kramer finally understood Rabbi Raff’s advice: “Put your tzitzis on your head and accept the job.” (What he meant was do not disguise your Judaism in anyway, and a kiddush Hashem will emerge. Wherever he went, Professor Kramer saw the fulfillment of Rabbi Raff’s instruction.)

Verifying the functionality of the defibrillators in a Russian hospital, a doctor found a solitary moment when Professor Kramer was alone to clandestinely whisper “shanah tovah” (even though the Jewish new year was long past). Every Jew who crossed Professor Kramer’s path somehow figured out a way to “bagel,” to give an explicit hint that he, too, was part of the Tribe.

With advancing age, Professor Kramer decided to start winding down his adrenaline adventures and increase his commitment to Torah learning. “With the guidance and assistance of Shamayim, I now work in the Wits University Medical School academic Emergency Department as a specialist consultant, teacher and mentor to undergraduate and postgraduate students and doctors,” he says, “with the rest of my day — between 10-12 hours — devoted to Torah study at the Maharsha Kollel.”

It seems like his pride in his heritage has been rubbing off on others. During Professor Kramer’s last week in Russia, he received a message that one of Moscow’s deputy mayors, Dr. Mikhalelevich, wished to see him. Professor Kramer was picked up and brought to the extravagant vice-mayor’s office. After some light conversation about the doctor’s family background, which Dr. Mikhalelevich hunched had stemmed from Russia, the vice-mayor announced that he wished to bestow a gift. The first were two CDs of a singer known as “the Russian Frank Sinatra,” who was Jewish. The second was a stunningly beautiful menorah made out of delft pottery that was worths tens of thousands of dollars. Professor Kramer was embarrassed to accept so much largesse, but in Russia, when dealing with government officials, refusal was not an option. Clearly, Mikhalelevich, like every other Russian Jew, felt the need to identify himself to this visibly Jewish visitor.

This was a moment that had to be captured for posterity, and Professor Kramer requested that a photograph be taken. Dr. Mikhalelevich agreed, but then excused himself for a few moments to a side room, saying he had to take care of something. Professor Kramer heard drawers opening and closing, until finally the vice-mayor emerged with a yarmulke on his head, too.

“Now,” Dr. Mikhalelevich pronounced triumphantly, “we can take a picture together.”

The two of them shook hands and embraced warmly, as a senior translator was left slack-jawed. How, he wondered, in a country were climate and suspicion enforced an air of coldness, could two men embrace in a warm bear hug after such a brief meeting?

Jews, even if they have never met, know the answer.

There is one other snapshot worth mentioning. After four weeks of fierce competition, the 2018 World Cup would be decided in a contest between Croatia and France, to be viewed by nearly half the world’s population. It was a pulsating match that France eventually dominated. After the final whistle, victory celebrations commenced with jumping, hugging, gold glitter, and champagne showers on the pitch. Suddenly four billion viewers uttered a collective “huh?” as a bearded man with a yarmulke congratulated the French coach, Didier Deschamps.

Professor Kramer still had some doping work to do after the game which brought him out on to the field, but to pass by the coach without extending his congratulations would not have been mentschlich. One always does what one has to do, but sometimes when you do the right thing, it’s even noticed.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.