Everyone’s Shtiebel

| October 13, 2024The shul opened in their friend’s memory keeps elevating his soul

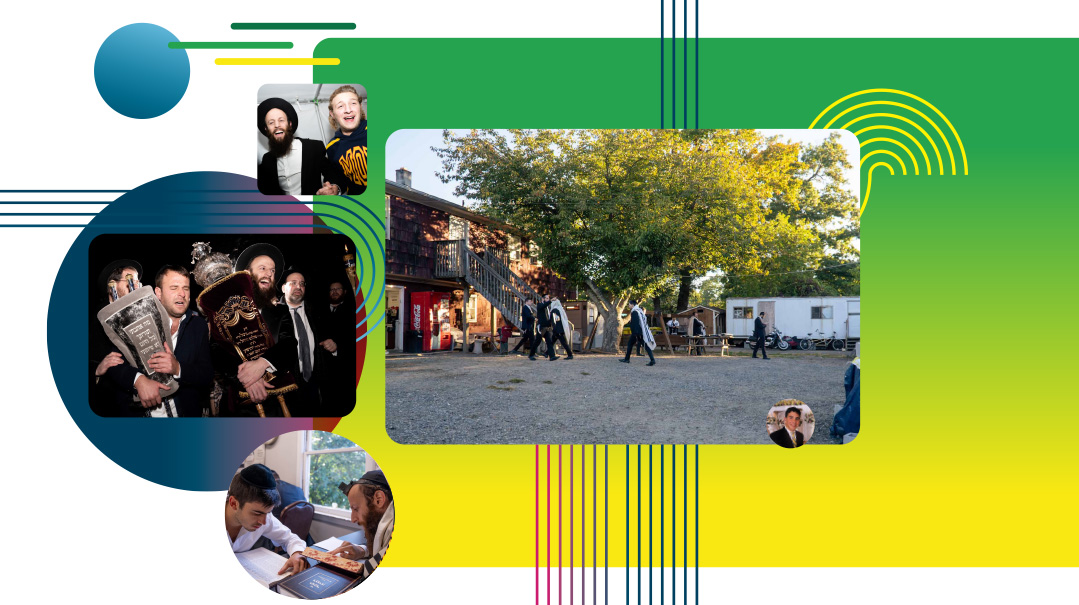

Photos: Chaim Bhatia and Yisroel Tesser

After Mordy Greenes’s sudden passing four years ago, a group of his friends opened a shtiebel in his honor — and the small shul mushroomed into a massive center for Torah, tefillah, chesed, and nonjudgmental ahavas Yisrael

It’s a Thursday night in the dead of winter.

The tire marks crisscrossing the dirt parking lot are filled with frozen puddles, and the frig id air penetrates the bones. But one of the large white all-weather tents at the end of the lot seems unaffected by the chill. Its canvas walls flutter gently in the breeze, and the entire structure is aglow from the bright light emanating from inside.

Plastered to the tent’s front door and all around the property are large signs reading, “Rosh Chodesh Seudah tonight at Mordy’s Shtiebel. Hot buffet, live music.” Car after car pulls into the lot, and a constant flow of people hurries from the cold air into the tent.

Once inside, it’s hard to believe it’s really winter out there. Large ducts inserted into holes in the canvas blast warm air. The tables lining the outer walls are covered with foil pans set in wire stands, blue flames flickering in the Sterno cans beneath them. The pans are filled with fan favorites: piping-hot sesame chicken, overnight potato kugel, and Yerushalmi kugel. Between the pans are trays of various flavors of Mike’s Chicken crunchers and bottles of cold seltzer and Coke, and people stand around, chatting and noshing.

Look up, and you’ll see the tent is illuminated by hundreds of tiny bulbs dangling from the top of the canopy, along with an impressive chandelier hanging from the center of the metal support beam. Look down, and you’ll take in assorted types of footwear — white sneakers, red flip-flops, classic black oxfords — on the deck’s simple plywood floorboards, which, despite its makeshift appearance, was designed to support the crowd at tonight’s event.

A small group sits around Moshe Groner, the talented musician leading tonight’s kumzitz. His thick beard and white shirt, coupled with his tan suspenders and mod glasses, set the tone for a relaxed atmosphere. To his right is the rav, Rabbi Binyomin Weinrib, whose piercing eyes are now closed tight in concentration, and to his left a percussionist. Guys in the crowd with bongos and guitars wait at the ready.

Moshe strums his guitar gently, and more people hurry to take their seats around him, some still holding cups of Coke and plates of kugel.

Dai-dai dai-dai dadai dai.

He starts humming the tune of the popular Berditchever Niggun, and the people assembled around him sing along. Once a sizable crowd is energetically singing the heartwarming niggun, Moshe suddenly slows the tempo. In a slight, almost inaudible undertone, he begins the words of a fresh track from the band Zusha.

It’s dark outside, but it’s light in here. It’s dark outside, but it’s light in here.

Many in the crowd seem unfamiliar with the lyrics, but the few who know it start intoning along with Moshe. In a few seconds, the guys pick up the catchy, stirring melody, and Moshe steadily speeds up the beat.

The sensation in the room is palpable; it will carry the crowd through the winter months ahead. The world is filled with confounding ideologies that cloud our vision, divisive viewpoints that make us take our eyes off the prize. But right here, in this warm tent on this icy night — we are one, jointly focused on the mission.

It’s dark outside, but it’s light in here.

Oops! We could not locate your form.