Everyone’s Nightmare

A year later, hostage families turn to Rav Dov Landau for support and solace

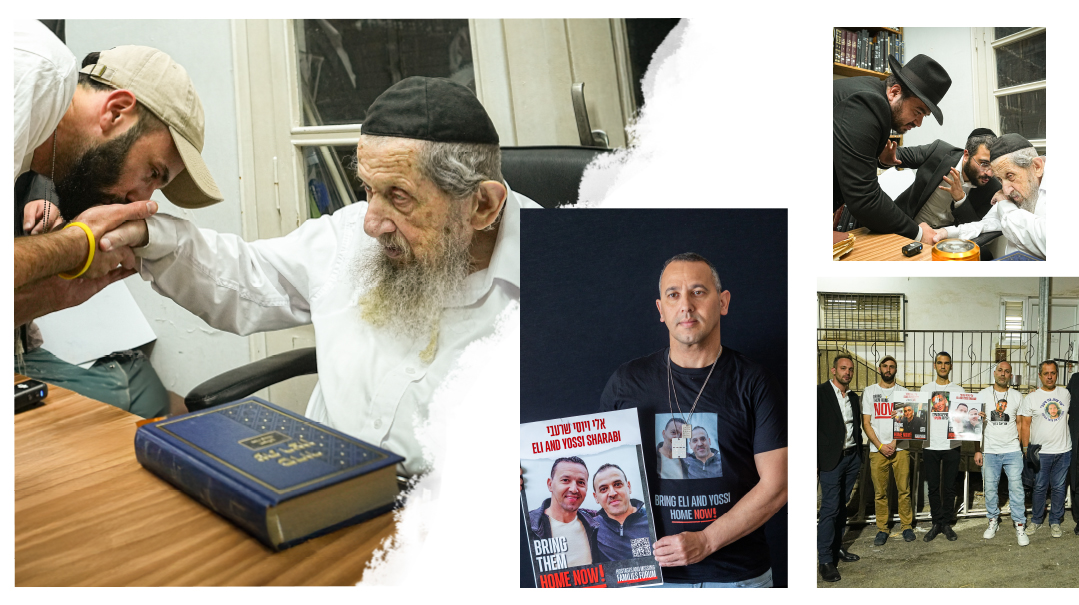

Photos: Yisrael Cohen and Elazar Feinstein

When family members of the hostages gathered together at the home of Rav Dov Landau for words of support and blessings, the feeling was surreal: They’d been in this room a year before, at the beginning of the war. How had an entire year passed with their loved ones still hanging on in their subterranean prisons, somehow clinging to life with guns to their heads?

AT the entrance to the modest house on Rav Sher Street in Bnei Brak, the five men wait anxiously — hunched, weary, but still with a faint spark of hope in their tired eyes. Over the past year, they’ve become unwilling ambassadors of an unimaginable reality as they hold pictures of their loved ones, those taken by force amid the mayhem and murder of their own families into the tunnels of darkness, the depths of the unknown.

Their fatigue is evident. Some of them are the captives’ only surviving close relatives. They’ve spent the past year shouting, meeting with ministers and Knesset members, addressing senators and parliamentarians, prime ministers and senior US officials, begging and protesting — always dragging along the pictures of their captive nieces or nephews, brothers or sisters, sons or daughters, mothers or fathers — sharing their relatives’ personal stories, describing the unfathomable torment they must be going through in their underground prisons, surrounded by madmen.

They never believed that, a year and a month after the devastating massacre, they would still be standing in public squares holding those pictures, fighting for their loved ones’ basic right to live.

But they’re not naive. They understand the complex reality in which they’re entangled, and they also know that people stopped listening to them long ago. Of course, everyone prays for the hostages, but the public attention that was focused on them during the first weeks and months of the war has faded. With a war of survival on multiple fronts, missiles falling, soldiers being killed daily, leaving young widows, orphans, and grieving parents, as well as a shifting international political landscape, their pain has been pushed off the top rung of the public agenda.

And yes, the leftist, oppositional political affiliation that identifies their group hasn’t done them any favors either. But at this point, they don’t care about right or left. They only want one thing: to see their family members come home alive in the best case, or to kever Yisrael in the worst.

And so they remain, clutching the photos of their loved ones, surrounded by their stories, memories, sleepless nights, and unending pain, upholding the responsibility to continue crying out on behalf of their relatives still trapped in the dank depths of Gaza.

And we’re with them as they wait their turn to enter, seeking once more the blessing of Slabodka Rosh Yeshivah Rav Dov Landau.

Our meeting takes place in the narrow slot called “between chavrusas,” for that’s how the 94-year-old sage’s day goes. One chavrusa follows another, many of them young bochurim who learn with a man considered to be one of the greatest living talmidei chachamim. His chavrusas and shiurim have been the only story for decades, and although he’s a rosh yeshivah, to him, “the Rosh Yeshivah” refers to his cousin and neighbor, Rav Moshe Hillel Hirsch, who also carries the yeshivah’s administrative burden.

It’s not the first time the hostage families are meeting with Rav Dov. At the war’s onset, they came here to ask for a blessing from the Rosh Yeshivah, who, absorbed as he is in the daily learning schedule that has defined him for the last 70 years, is a true empathizer with the pain of every Yid.

Perhaps Rav Landau’s background gives a clue to those connective abilities. He was raised in Rechovot of the 1930s, during an influx of Yemenite immigrants, and he grew up with the Yemenite kehillah. And while he’s considered today’s spiritual inheritor of the Chazon Ish, both his grandfather and his first cousin were Strikover Rebbes, and Rav Dov has always found his place there as well. Slabodka has many chassidishe talmidim, although Rav Dov, despite his lineage, is far from being a practicing chassid. Still, many contemporary chassidishe rebbes and mashpi’im are his talmidim, including Rav Tzvi Meir Zilberberg, a close talmid from his years in Slabodka, and rosh yeshivah Rav Shaul Alter of Gur/Pnei Menachem.

A year after Rav Dov’s first meeting with families of hostages, the situation hasn’t changed much for them — only the number of days they’ve been waiting for salvation has grown, while the hostages’ chances of survival dwindle from day to day.

Now they’ve returned, seeking once more the blessing and empathy of the Rosh Yeshivah, a meeting facilitated by Rabbi David Druk of the Kissufim organization and Yisrael Cohen, the marked chareidi presence hovering around the Hostage Family Forum since the beginning of the war.

“Some of the families, who under normal circumstances are on the opposite end of Israel’s religious spectrum, felt that the chareidim were not advocating for them and didn’t really care,” Cohen explains. “But these are not normal times, and we understood the importance of uniting the nation and sanctifying G-d’s name.

“And beyond mutual responsibility, many of the families are traditional, and a connection to Israel’s Torah leaders is very important to them,” he adds. “But even families less connected to the religious world have been interested in meeting with rabbanim for blessings and guidance, some of them taking on Shabbos, prayer, and Torah study.”

Just before this past Succos, Rabbi Druk organized a tour of Bnei Brak for the families of hostages, where he introduced them to Rebbetzin Leah Kolodetzky, Rav Chaim Kanievsky’s daughter, who is known for her own power of blessing. The Rebbetzin encouraged the families to add acts of kindness to their day, to take on an additional halachah, and not to speak ill of others as a zechus for their loved ones. She told the group that since the October 7 massacre, her own husband, Rav Yitzchak Kolodetzky, has forfeited his bed and has been sleeping on the floor in identification with the hostages. (Toward the end of the winter, Rav Kolodetsky, 70, contracted a bad cold from sleeping on the floor, and since then he swapped the mattress on his bed for a wooden plank on which he sleeps.)

Last November, in a heartbreaking encounter organized by Yisrael Cohen, orphaned children from Ofakim whose father was murdered by Hamas terrorists on the way to Simchas Torah davening, received brachos and chizuk from Rav Dov Landau, but not before the Rosh Yeshivah burst into tears.

And in a separate visit, Avichai Brodutch, whose wife Hagar and their three children were abducted from their home in Kfar Aza, joined with other hostage families in a meeting with Rav Landau, who wept openly for their plight, blessing Brodutch and the others with hope for the swift and safe return of their families and all the other abductees.

Brodutch went out to defend the kibbutz while his family, along with their three-year-old neighbor Avigail Idan, who fled to the Brodutch home after her parents were murdered, were hiding in their sealed room. When he returned, wounded, to check on his family, they were gone — and he initially thought they were dead. Hagar, her children, and Avigail were in fact released at the end of November.

Last year, the Rosh Yeshivah had received the group with tears, sharing in their unfathomable pain and offering guidance to slightly ease the emotional toll of waiting and worrying. Now they had come for another dose of strength, a few more uplifting words to give them the resilience to keep hoping, praying, and waiting for the miracle.

The Border of Despair

Now, standing outside waiting to go in are Malki Shem Tov, the father of Omer, who was kidnapped and is being held by Hamas; Sharon Sharabi, whose brother Eli is still being held by Hamas (Eli’s wife and two daughters were murdered) while his brother Yossi was murdered in captivity; Roi Baruch, whose brother Uriel was abducted and murdered in captivity; Levi Ben Baruch, uncle of Idan Alexander, an Israeli-American lone soldier from Tenafly, New Jersey, who was kidnapped and remains in captivity; and Yuval Bar-On, whose in-laws, Keith and Aviva Siegel, residents of Kibbutz Kfar Aza to where they made aliyah 40 years ago, were abducted into Gaza’s tunnels. Aviva Siegel was released in a hostage exchange while her husband remains captive. (“I can’t understand how you’re still in there,” she wrote in a recent open letter to her husband. “I can’t understand how the world is silent. I can’t understand how people hear the terrible stories I tell of what we went through and what you’re still going through, and the sun keeps rising and setting, while you’re stuck in this nightmare.”)

“We are exhausted, wrung out mentally and physically,” says Sharon Sharabi. “But we can’t stop, and can’t sink into despair. Our loved ones are there, and even though the public attention isn’t what it used to be, we’re obligated to continue fighting for them.”

Roi Baruch, whose brother Uriel was murdered in captivity, is visibly tense. “I’ve already lost my brother,” he says quietly, his voice heavy with pain. “I want the Rabbi to guide us on what we should do now. We hope they’ll return his body so we can bury him according to Jewish law and have a gravesite where we can recite Kaddish. We don’t even have that.

“And you know, even though my family’s personal story essentially ended when we were informed of Uriel’s murder, I still feel obligated to continue. It’s about bringing Uriel’s body back and ensuring those still alive return home.”

How Can I Help?

The door opens, and we step inside. The modest and extremely simple home is a surprise for hostage family members entering for the first time. They are struck by the physical austerity — this is a home whose walls are steeped in Torah, where critical issues are discussed and decisions affecting Klal Yisrael made.

The families hold pictures of their loved ones, people cruelly torn from their lives, while the Rosh Yeshivah’s son, Rav Yossi Landau, opens the conversation by introducing the guests:

“These are family members of the hostages still held by Hamas in Gaza,” he tells his father.

Before a word is spoken, the Rosh Yeshivah’s deep pain is unmistakable. He scans the room, his eyes moving from one person to another, reflecting a profound sense of shared grief and burden.

The tension in the room is palpable. The family members sit in respectful silence, waiting for the Rosh Yeshivah to speak. After a long moment of quiet, he closes his eyes in sorrow.

The Rosh Yeshivah then fixes his gaze on the pictures and posters the families are holding, inviting his visitors to share about their loved ones. Sharon Sharabi is the first to speak:

“I visited the Rav many months ago,” Sharabi tells the Rosh Yeshivah. “At the time, the Rav told me to recite Tehillim chapter thirteen every day. I want to tell the Rav that I’ve been doing so — not just me but in dozens of synagogues across the country, people are reciting this chapter daily for the return of our family members.”

The Rosh Yeshivah asks him to share more about his brothers, and Sharabi continues in a broken voice:

“Eli, my brother, lived in Kibbutz Be’eri. Terrorists murdered his wife and two daughters, ages sixteen and thirteen, before hauling him off to Gaza. Yossi, my other brother, was also kidnapped and later murdered in captivity. We pray every day for Eli’s return.”

Who can talk after that? But the Rosh Yeshivah turns his attention to Levi Ben Baruch, uncle of Idan Alexander.

“Idan made aliyah from the United States alone to fight for the people of Israel,” Ben Baruch tells the Rosh Yeshivah. “Most of his family remained in New Jersey, but he came here out of a sense of mission.”

The Rosh Yeshivah asks Ben Baruch what he knows about Idan’s current situation. “Those who were released in the early exchange deal reported seeing him alive and uninjured in the early days of captivity,” Ben Baruch says. “Idan even spoke with them, trying to reassure them.”

Malki Shem Tov, Omer’s father, tells the Rosh Yeshivah that Omer would be marking his 22nd birthday the next day — in captivity.

“This is Omer’s second birthday in captivity,” he tells the Rosh Yeshivah. “He was 21 when he was kidnapped, and now it’s been over four hundred days of unimaginable suffering.”

Suddenly the Rosh Yeshivah, practically in tears, asks the family members sitting around the table, “Tell me, how do you sleep at night?” His voice cracks, tears now rolling down unchecked. “How can one sleep at night while living in such a terrible reality?”

The room falls silent. There is no answer. One person quietly admits that even sleeping pills no longer work.

But the Rosh Yeshivah isn’t finished.

“I’ve thought of a way to strengthen you, to give you chizuk,” he says. “Establish a Torah study session, once a week or once every two weeks. Invite neighbors, friends, and those who know you and your loved ones in captivity. You don’t need a large group. Ten, fifteen people, gathering to study for the merit of your loved ones or in memory of those who, Rachmana litzlan, are no longer with us.

“You can ask a rabbi to give a Torah class on the weekly parshah. This will undoubtedly inspire the community and help your neighbors and friends remember your horrific tzaar. While you live this pain every moment, others need a connection to remind them to pray and act, and this will help others share in your struggle.”

We’re With You

“Rosh Yeshivah,” asks Malki Shem Tov, “as you know, much discussion surrounds a potential deal to exchange Hamas prisoners for our children. The Prime Minister refuses, fearing it will lead to more terror. What is the Rosh Yeshivah’s view on this matter?”

The Rosh Yeshivah responds thoughtfully, “This is both a public and political issue, a deep and complex matter. But I will say this: Decisions involving life and death require profound deliberation by those fully informed of the details. On the other hand, when considering such matters, one must also think as if it were one’s own child.”

The Rosh Yeshivah clasped his hands together in sorrow. “What more can be said? We are a nation of faith, believing that everything is from Hashem. It’s upon us to increase our prayers, to turn to Hashem, to ask and plead.”

Sifrei Tehillim are brought out from a cabinet and handed out to the family reps. At the Rosh Yeshivah’s instruction, everyone opens to chapter 13, where he will say a verse and those around the table will repeat.

Thus begins the communal recitation of Tehillim. The families, filled with tears and emotion, respond after him. “For the Conductor, a Psalm of David,” the Rosh Yeshivah begins, and the families echo his words. “How long, Hashem, will You forget me forever? How long will You hide Your face from me?”

Closing the sefer, the Rosh Yeshivah raises his eyes and looks at those gathered around him. “I’m praying with you that the Holy One, Blessed be He, will help ensure that all your prayers are heard — your prayers, our prayers, and the prayers of every Jew who cares. May these prayers ascend before the Master of the Universe, and may He guide us with mercy.”

One by one, the family members approach to shake the Rosh Yeshivah’s hand and he gives each one an individual blessing, even though there’s a line outside stretching all the way down the street. “May we have salvations speedily,” he tells each one as he closes his eyes and clasps their hand. “Be strong. The Jewish people are with you.”

Before we leave, Malki Shem Tov raises a painful point: “Kevod HaRav,” he says, “the public is no longer so engaged with our cause. We’re afraid people are forgetting our loved ones who remain in captivity. At the beginning of the war, all of Israel stood with us. Now, we feel forgotten. Often, we have to remind people that our children, our siblings, our parents are still in Hamas tunnels.”

“The public must continue to remember and continue to pray,” the Rosh Yeshivah says. “Our moral duty is to stay attuned to this suffering. I call on every Jew, wherever they may be, to increase their Torah study and good deeds, to dedicate their prayers to the safe return of your loved ones, and to strive for unity and sanctification of G-d’s name during these difficult times.”

The Rosh Yeshivah looks at Shem Tov, his face reflecting deep pain and empathy. “The fact that we gathered here is, in itself, an important statement,” the Rosh Yeshivah says. “To remember and to pray, all of us, no matter what our affiliation. We certainly have an obligation to share in this unbearable burden. This is not something that a Jew should bear alone. We are all with you in this nightmare, strengthening and praying together with you.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1037)

Oops! We could not locate your form.