Every Heart Was Broken That Yom Kippur

| October 8, 2024During the holiest day of the year, the devastating news made its rounds through the shuls of Jerusalem

Title: Every Heart Was Broken That Yom Kippur

Location: Jerusalem, Israel

Document: Detroit Jewish News

Time: October 1959

On the eve of Rosh Hashanah 5720 (1959), a distinguished Jerusalemite Jew disembarked from a plane at Lod Airport, carefully carrying a bundle of packages. As he presented his belongings to the customs officer, he gestured toward one package and said, “Please handle with care — these are two esrogim. They’re susceptible to damage and could become invalidated.”

The customs officer examined the two exquisite esrogim, leafed through the regulations manual, consulted with his superiors, and finally declared, “These esrogim were brought in contravention of the Ministry of Agriculture’s regulations from the Plant Protection Department.”

Despite impassioned pleas and arguments, the verdict remained firm. The officer proceeded to slice the precious esrogim into pieces, rendering them useless.

The Jerusalemite, Rabbi Naftali Halberstam, a man of patience and grace, accepted the fate of the treasured esrogim. He had brought them specifically for the Brisker Rav, Rabbi Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik, known to his talmidim as Rav Velvel, who was renowned for his meticulous observance of halachah.

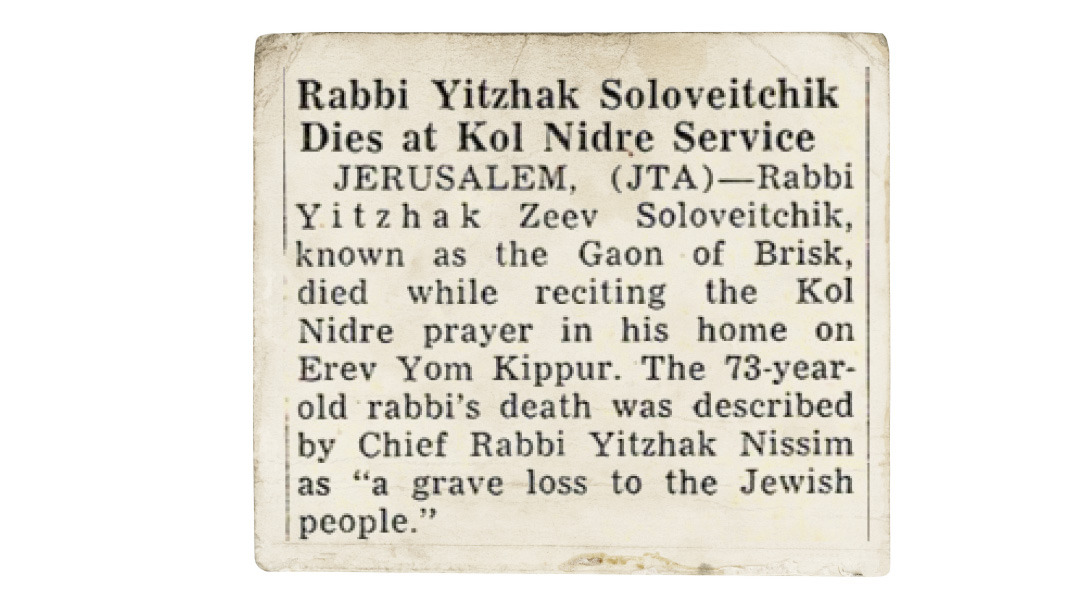

Only ten days later, it became evident that those esrogim, brought with such care and devotion to serve a specific halachic purpose — ensuring there would be esrogim not grown in a Shemittah year — would no longer be needed by the Brisker Rav. As the holy ark was opened for Kol Nidrei that Yom Kippur eve, Rav Velvel ascended to the Heavens–and the revered Brisker Rav returned his pure soul to its Maker.

His talmidim later recalled how, just before Rosh Hashanah, when they implored him to be with them during the Yamim Noraim, Rav Velvel responded with characteristic candor, “We will be together on Rosh Hashanah, but being here for Yom Kippur is a luxury.”

And so, as the world stood in judgment, the esteemed Raavad of Brisk was summoned to the Heavenly Court. Thousands gathered from across Jerusalem and beyond, mourning the passing of the Torah giant of the generation. As they escorted him to his final resting place, they parted from a gadol who had not only taught Torah but served as a meilitz yosher for all of Klal Yisrael, ascending to his eternal place on the eve of Yom Hakippurim.

ON February 19, 1941, Rav Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik, known as Rav Velveleh — or more widely by his moniker the Brisker Rav — arrived in Jerusalem. This was the consummation of a year-and-a-half-long journey of escape from war-torn Europe that began in September 1939. Seven of his children were able to escape with him. But due to an unfortunate set of circumstances, his wife, Rebbetzin Hindel, and three of their children — two sons, ages four and five, and his 15-year-old daughter Gittel —remained behind in Brisk, where they were murdered by the Nazis in the Holocaust.

The war years, his harrowing escape, the loss of his wife and children, and raising his surviving family under demanding financial circumstances all took a steep toll on his health, already weakened. Despite all of his travails, he continued to teach Torah to his sons and a select group of elite students, and took a surprisingly active role in leadership of the Torah community in its many campaigns during the early years of the State of Israel.

The Brisker Rav had always suffered from ill health and severe asthma, and in his last years, his debilitated physical condition forced him to curtail his activities. But he still managed to muster energy to advocate for the issues he deemed critically important.

During the last weeks of his life, he waged his final campaign. Elections for the fourth Knesset were to be held on November 3, 1959, and many in the Agudas Yisrael and Mizrachi political parties wanted to run as a joint religious bloc. They had already done this in 1949 with great success, and many party activists, along with several members of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudas Yisrael, wanted to replicate this victory and enhance their power in the upcoming Knesset. They were especially hoping to gain leverage on the vexing issue of drafting yeshivah students.

The Brisker Rav was firmly opposed to any union between Agudas Yisrael and Mizrachi. He waged a sophisticated crusade to persuade the Agudah leadership to his position, despite the fact that he was not formally associated with that party, had never supported it in previous elections, and held no position within it or on its rabbinical board. In return for Agudas Yisrael following his position, he promised to publicly support the party in the upcoming elections.

When he ultimately prevailed, the Brisker Rav felt obligated to express public support for the Agudah, as per his commitment, despite his general aversion to doing so. To solve this quandary, he dug up an old election poster that he had authored, signed, and publicly distributed in 1928 during a contentious election for kahal membership while he was rabbi of Brisk. In that proclamation, he had called upon the Brisk community to vote for chareidi representatives on the Vaad Hakehillah. He commissioned Moshe Schonfeld to translate the original from Yiddish to Hebrew, then reviewed the translation to approve, and finally signed it and authorized its publication. In this fashion, he supported voting for Agudas Yisrael in the Knesset elections without ever writing a special letter or proclamation on their behalf, or even mentioning them by name.

The elections were to be held in the immediate aftermath of the Yom Tov season that year, and Agudas Yisrael planned on publicizing the translated letter from 1928 in close proximity to election day in order to maximize its impact. On Erev Yom Kippur, the Brisker Rav passed away, and his letter was therefore only published after his passing. As a result, and because of the ambiguous nature of the proclamation, both the Mizrachi party as well as the extremist Neturei Karta (who were opposed to any participation in elections whatsoever), claimed that it was a forgery. However, many great people and close associates of the Brisker Rav, including Rav Aharon Kotler, attested to its authenticity.

On Erev Yom Kippur 1959, the Brisker Rav’s illness peaked and he lost consciousness, his face contorted in pain. Though he was mumbling much of the time, his words were incomprehensible, aside from an occasional prayer for rachamim merubim (an abundance of mercy). Ever since he had settled in Jerusalem, there had been a minyan in his home. It was a few minutes before shkiah, and the minyan in the next room was just commencing the recital of Kol Nidrei with the onset of Yom Kippur, when the Brisker Rav breathed his last.

During the holiest day of the year, the devastating news made its rounds through the shuls of Jerusalem. The levayah was held on Motzaei Yom Kippur. The large funeral entourage exited his home on Rechov Press and walked all the way to Har Hamenuchos, where he was buried in the center of the newly consecrated chelkas harabbanim near the entrance of the cemetery.

The End of Brisk, the Beginning of Brisk

In his hesped, Rav Elazar Menachem Shach, a close talmid, cried out, “We have now lost the entire house of Brisk — the Beis HaLevi, Rav Chaim Brisker, and the Brisker Rav!”

Following the Brisker Rav’s passing, the landlord of his apartment on Rechov Press insisted that the property be vacated, as the contract was now void. His son Rav Raphael contested this on the grounds that the original contract stipulated that the apartment would not be used exclusively for residential purposes and would host a steady minyan as well. Since the minyan continued even in the absence of the Brisker Rav, the landlord couldn’t void the contract. The case dragged on for years until the exasperated landlord put the property up for sale. It was ultimately purchased by Yeshivas Brisk of Rav Berel Soloveitchik, and the sound of Torah continues to emanate from the original home of the Brisker Rav until this very day.

Brisk for Life

The Brisker Rav’s son-in-law, Rav Michel Feinstein, related to Rabbi Shlomo Lorincz: “On the last Shabbos of his life, he turned to his son Rav Meir and said, ‘It’s not good for a Jew like me, who is used to conducting himself exclusively according to the dictates of the Shulchan Aruch, to be sick, because the illness makes doing so very difficult.’ The illness and the suffering didn’t bother him. His only pain was that he was unable to conduct himself according to the Shulchan Aruch.

“Even as he lay on his deathbed, he didn’t stop thinking about his public responsibilities. He knew very well how concerned the Torah community was for his health, and for that reason, he kept his illness a secret as long as he could. He forbade me to disclose either the name of the illness or any details regarding it. If the community knew the nature of his illness, it would become a subject of discussion among bnei Torah and talmidei chachamim. Since there would be no benefit to be gained from such discussions, he would be the indirect cause of idle talk. The Brisker Rav succeeded. The details of his illness were never publicized, and he didn’t become the cause of what would have constituted in his view devarim beteilim, idle talk that distracts one from Torah learning.”

The research and writings of Rav Shlomo Lorincz, B. Glaberson, Naftali Rotenberg and Yair Halevi were utilized in the preparation of this column.

The 65th yahrtzeit of Rav Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik, the Brisker Rav, is 9 Tishrei.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1032)

Oops! We could not locate your form.