Enduring Gifts

The pride I feel in being part of a very special people has only grown and grown since October 7

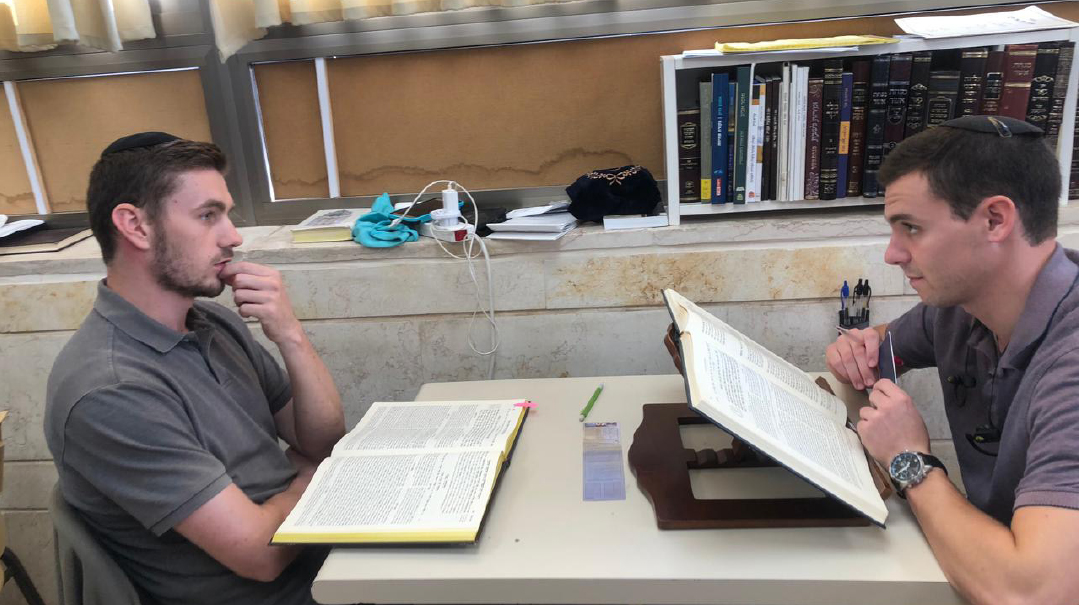

Two longtime chavrusas, Yakir Hexter and David Schwartz Hashem yinkom damam, learned together and died together

T

he loss of any Jewish life is a loss for all of us. That is not just a platitude to which we give lip service, but a feeling that we should live with. Indeed, part of the impetus for my recently published collection, Ordinary Greatness, was to bring that point home.

But if that is true for every Jewish life lost, how much more so when that life was lost defending us from threat. As the late Mirrer rosh yeshivah Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz famously said in a shmuess during wartime, “Anyone who does not feel hakaras hatov to Israeli soldiers has no place in this beis medrash.”

That is why for the last three months I have forced myself to begin the morning by looking at the photos of the IDF soldiers whose deaths were announced since the previous day. I think that every Jew in the world should be doing the same, not just those of us who live in Israel.

Admittedly, I have a strong bias for Jewish faces, and those killed in combat strike me as uniformly handsome. But what stands out more than the physical beauty is the seriousness and depth one sees in their faces — reminiscent of photos on the walls of Acco Prison of the young Irgun members executed by the British.

Nearly 50 percent of the casualties to date are religious soldiers, many of them reservists with wives and children. On a recent segment of the Halacha Headlines radio show, Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Rimon, rav of Gush Etzion, rosh yeshivah of Machon Lev, and the author of numerous halachic seforim, used the sh’eilos asked of him by soldiers in combat to convey his own awe at the quality of those serving in the IDF. One soldier asked whether he could charge his cell phone in a Palestinian home — i.e., whether the home’s electricity is permitted shalal (booty). Another group of soldiers wondered about lighting Chanukah candles when doing so might alert Hamas forces to their location.

Not all the halachic queries came from the soldiers themselves. The wife of one of the fighters, who was still childless after a number of years of marriage, asked Rabbi Rimon whether she could inform her husband of a positive pregnancy test. Her question was based upon a Rambam (Hilchos Melachim 7:15) stating that a soldier in a commanded war should not distract himself with thoughts of his wife or children.

These soldiers were not just religious, but serious lomdei Torah. Rabbi Ari Wasserman, the host of the aforementioned Halacha Headlines show, read an email from one soldier in which he described how his unit was about to make a siyum on Megillah. Another asked whether he could be maavir sedra with Targum a week early, in case he was in combat the entire following week and had no opportunity.

Reb Ari, who is a close friend and once-a-week chavrusa, dedicated one week’s show to two longtime chavrusas from Yeshivat Har Tzion, Reb Yakir Hexter and Reb David Schwartz, who were killed together earlier in the week. They were friends from high school, through yeshivah, army, and officer training.

My friend Rabbi Moshe Taragin, a ram at the yeshivah, eulogized them in the Jerusalem Post last Friday. Yakir Hexter, he wrote, was at once immensely driven, holding himself to the extremely high standards of Mesillas Yesharim, and tolerant of those who couldn’t or wouldn’t meet his exacting standards. David Schwartz, despite being raised in the national-religious world and institutions, was drawn to chassidus, to rebbes and tishen, and prevailed upon Rabbi Taragin to give a weekly shiur in chassidus.

Yakir was the son of Reb Ari’s very-early-morning chavrusa of more than a decade. Just a few days earlier, Reb Ari had met Yakir at a chasunah and asked him whether he was nervous. He replied that he was not, as they were doing what had to be done.

At the Hexter family shivah house, which I went to together with Rabbi Wasserman, I listened as Yakir’s father describe his son’s eagerness to help others and his unusual sensitivity. Yakir always wore a suit and tie for Shabbos, a notable departure from the normal Shabbos attire at his yeshivah. The only exception was when his father — himself an alumnus of Yeshivat Har Tzion — came for a parents’ shabbaton. Yakir knew that his father (and chavrusa for learning Mesillas Yesharim) would not be wearing a tie, so he did not either.

THE PRIDE I FEEL in being part of a very special people has only grown and grown since October 7, and I would guess that feeling is almost universal among identified Jews. Though I have focused until now primarily on religious Jews, that pride is not confined to them. Historian Michael Oren’s description of Israeli society as the strongest and most resilient in the world, upon the hundredth day of the war, strikes me as true.

What other country could continue to function with hundreds of thousands of citizens uprooted from their homes on the northern and southern borders indefinitely, and hundreds of thousands more reservists away from their families and jobs for that entire time? One hundred percent of reservists answered their call-up notices, including tens of thousands who returned immediately from abroad. And in many units, 50 percent more than the number of those called up reported for duty, which they knew in advance would be dangerous and arduous.

The amount of private philanthropy and volunteerism needed to maintain some modicum of normalcy has been remarkable. One of my daughters-in-law shared with me yesterday the inspiration she had from preparing meals together with Mrs. Devorah Ebbing and Mrs. Laiky Lehrfeld, her neighbors from Ramat Beit Shemesh. Since just after Simchas Torah, their Mazon Campaign has been sending approximately 300 gourmet meals a week, made from whatever ingredients are on sale, to soldiers stationed on the northern and southern borders. Recently, their meals added to the joy of a siyum held by a unit in Gaza itself.

For the numerous volunteers who do the shopping and make the meals (including special vegan ones upon request), for the neighborhood children who pack the special containers that ensure the meals arrive still piping hot, and for the senior citizen who drives to the furthest borders to deliver them three times a week, “doing something good is their means of retaining some equilibrium.” Their reward is the excitement of the soldiers who feel the love and support in each meal that replaces their usual army rations.

And I am describing only one of thousands such private initiatives around Israel.

I keep coming back to the nearly unfathomable emunah of the fallen and their families. David Schwartz had three handwritten messages, based on the words of Chazal or pesukim, above his bed so they would be the last things he saw at night before going to sleep: 1) Hakol bidei Shamayim; 2) Haboteiach b’Hashem chesed yisovevenu — One who trusts in Hashem, kindness surrounds him (Tehillim 32:10); and 3) Ani b’chasdecha batachti — But as for me, I trust in Your kindness (Tehillim 13:6).

That is typical of the way emunah and bitachon are constant subjects in the Hesder yeshivot. On an overnight stay in Mitzpeh Rimon last winter, I davened Shacharis in the local Hesder yeshivah. One thing that struck me was that the private bookshelves on each desk were uniformly filled with sifrei hashkafah, both contemporary and the classics.

By now, I presume most readers have viewed at least once the six-minute clip of Hadas Lowenstern speaking of her late husband, Rabbi Elisha Lowenstern, who was killed when his tank was hit while trying to rescue wounded soldiers. Not once in the video does a smile leave her face, as she talks about her 13 years together with “the love of my life” and their six children, ranging in age from ten months to 12. She chooses to speak more about her husband’s learning sedorim, Rambam yomis, translating Gemara into English, Mishnayos, his morning run before the haneitz minyan, than about the circumstances of his death.

“To me, his death is beside the point,” she says. “He only died once, but I can speak about his life. I’m alive. Our six kids are alive. And this is our plan. We plan on living such a wonderful life that our enemies could never imagine. We will live here in Eretz Yisrael; we will study Torah; we will perform mitzvos. We will be a happy Jewish family. And this is true victory, in my eyes at least.”

She is filled with her consciousness of herself as part of the Jewish People, and relates how she is strengthened by her awareness “of all those davening for us, not speaking lashon hara for us,” and how all Jews will rejoice together in Jerusalem with the coming of Mashiach.

Professor Joshua Berman describes, in a blog post at Times of Israel, a new Israeli ritual of reading at the shivah for fallen soldiers the letters they left behind only to be opened in case they did not return from combat. I first became aware of this phenomenon during the 2014 Operation Pillar of Fire. At the time, I was astounded how even seemingly secular soldiers wrote of their joy in having fallen while protecting the Jewish People, with the Jewish People preceding even loved ones and the homeland.

What takes away the breath from the letters quoted by Professor Berman is the calm, even happiness, with which the soldiers contemplate their own deaths, which are no abstraction as they head into battle. Some are only on the cusp of adulthood, not yet having been zocheh to marriage and children, and others already in their mid-forties and fathers of large families, like Rabbi Yossi Hershkovitz, a prominent national-religious educator in Jerusalem.

The best-known such letter for English-speakers is likely that of Binyamin Sussman, as there is a clip of his parents and grandmother reading the letter aloud. On the eve of his death, he wrote, “No one is more content right now than I am. I am about to fulfill my life dream... to defend our beautiful land and the people of Israel.” On multiple occasions, he adjured his parents that if he were to be captured, they should not permit him to be exchanged for a single terrorist.

“I don’t regret for a second that I chose to serve in a combat unit,” Itai Yehudah wrote his parents . “This is the best thing I ever did.”

Captain Liron Snir’s last words to his loved ones were, “I’m happy about the life I lived, what I did, what I was, on behalf of my people.”

Shai Aroussi assured his parents that his life was “not a waste” and his death “entirely worth it,” because he was doing what he had always wanted to do since he was a little boy: “saving people and protecting the country.”

High school principal Rabbi Yossi Hershkovitz thanked his parents for “show[ing] me a path through life where the question is not ‘what do I have coming to me,’ but how at every moment I can give more for the people and for the country.”

THE MORE THE JEWS of Israel have learned about themselves and each other over the past three months, the closer and more united they have become. I’m haunted by the clip of a soldier in a wheelchair, with his leg amputated, and after three months lying in hospital, nevertheless saying, “We sacrificed for one thing — to see Am Yisrael united and going on kiddush Hashem.” If there is one lesson from the time of Moshe Rabbeinu, “it is that if we are not united, there is no hope.” And if this war was the means of bringing about unity, he says, “it was worth losing my leg.”

Eldad Yaniv, one of the leaders of the demonstrations against judicial reform, spoke for many: “I was in Tel Aviv, in my milieu, and I didn’t know these people [the national-religious]. You listen to an interview with this amazing woman [perhaps Hadas Lowenstern]; you speak to the families of the fallen; you read the letters of the soldiers, and you think, ‘Such a great part of our nation I didn’t know.’

“And I’m happy to know them now. I’m moved by knowing them. And I’m klopping Al Cheit on the fact that I did not know them until now.”

May none of us ever have to klop Al Cheit again over the fact that we did not know or appreciate the greatness or our fellow Jews. —

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 996. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.