Enduring Edifice

If we offered rock-solid chinuch in emunah with frum foundations it would be harder for the young generation to stray from the path

In Sadigura the shocking news traveled like lightning — the old kloiz the majestic shul designed with the deep kavanos of the holy Ruzhiner Rebbe was still standing having somehow survived the Nazis and the Soviets. In a moving conversation with Mishpacha the Sadiger Rebbe discusses the heiliger Ruzhiner’s secret and the intertwined destinies of the shul and the chassidus both built on that same spiritual bedrock.

Reb Chaim Kaufman had just returned to his Antwerp home and there was one thing on his mind. He had to speak to the son of the Sadiger Rebbe. The sight he’d seen would mean worlds to the Rebbe and to the chassidus.

At the time in the 1980s the Rebbe’s son Rav Yisrael Moshe — who is the Rebbe today — was living in London and Kaufman wasted no time giving him the news.

“I’ve just returned from Sadigura” he said. “True it’s under Communist control but I traveled to Moscow and once I was inside Soviet territory I managed to get to the village. And you’ll never believe what I found!”

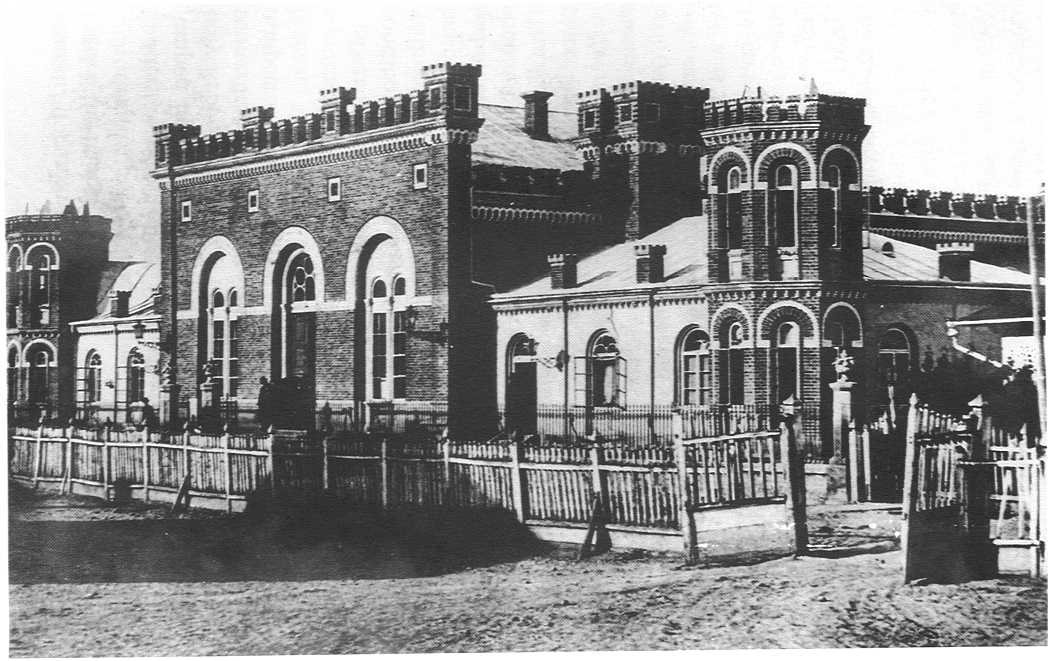

On his covert trip to the village Reb Chaim Kaufman — a loyal chassid — had managed to locate the final resting places of the court’s rebbes. But that wasn’t all he’d discovered. Contrary to popular belief the legendary Sadiger kloiz — for generations the spiritual locus of the Sadigura branch of the Ruzhiner dynasty — was still standing. In fact Kaufman managed to photograph the exterior of the kloiz and his photos attested that the building which was so much more than a physical structure had survived the most daunting of odds.

Today’s Rebbe still remembers those fraught moments. As soon as he saw the photographs he immediately phoned his father the previous Rebbe zy”a and told him that the kloiz was still standing. The Rebbe became extremely emotional; for years he had waited and wondered about the fate of the kloiz. Now that he knew it had survived World War II and the Soviet occupation he was more determined than ever to reclaim the building and restore it as a spiritual center.

It’s been three decades since the disclosure but the story is finally coming full circle. The current Rebbe of Sadigura has taken his father’s mantle — along with his quest to restore the kloiz. After decades of behind-the-scenes maneuvering intense prayer and hard labor the quest is finally nearing closure. At the beginning of the upcoming year he hopes to lead a delegation of chassidim back to the village where the story all began

.

Gold and Dust

Here at 10 Gutmacher Street in Bnei Brak of 2016, time seems to stand still. Inside the residence of the Sadiger Rebbe, there’s a long table covered with an embroidered tablecloth, a gold clock, a stack of seforim, and a pile of kvittlach. Nobility, wisdom, and heartfelt compassion all fuse here in the Bnei Brak hoif.

Rav Yisrael Moshe Friedman of Sadigura is a seventh-generation, direct descendent of the holy Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin zy”a (“the heiliger Ruzhiner”), founder of the multibranched dynasty. Even 165 years after his passing, the Ruzhiner Rebbe’s influence shapes the many chassidic courts that comprise his dynasty, and his unique approach to avodas Hashem still marks his successors.

The six holy forebears of the current Sadiger Rebbe include his father, Rav Avraham Yaakov, the Ikvei Abirim; his grandfather, Rav Mordechai Shalom Yosef, the Knesses Mordechai; Rav Aharon, the Kedushas Aharon; Rav Yisrael, the Ohr Yisrael; and the Alter Rebbe — the Admor Hazakein — Rav Avraham Yaakov. He was the second son of the Ruzhiner Rebbe and served as Rebbe in the town of Sadigura.

A moment after crossing the threshold, when the golden klamke (doorknob) clicks closed, I’m suddenly swept into another world. It’s a world of the 21st century, but which still draws its substance and secret from the hoif in the Sadigura of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 150 years ago.

I’m greeted by warm, penetrating eyes that seem to envelop me with genuine ahavas Yisrael. The Rebbe asks my name, how I am, about my family, and what I do. That is the Ruzhiner way — to take an interest in the welfare of every person who enters the hoif, and to then envelop him in a shower of positivity.

The Rebbe is composed and gentle, and yet I’m overcome with awe and even fear. Clearly, Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin bequeathed to his successors an eminence and a presence that is passed from father to son — characterized by a combination of love of Hashem, boundless ahavas Yisrael, and the nobility and clarity of mind that guides their every action.

Ruzhin is known for its link to majesty — not only the spiritual majesty of an elevated chassidic leader, but also the physical manifestation of royalty. The Rebbe reflects on the true nature of that majesty.

“Dovid Hamelech was, as we know, lowlier in his own eyes than any other person,” the Rebbe explains. “In Sefer Tehillim we find extreme descriptions of his humility — descriptions of his broken heart, his self-comparisons to a pauper. A typical king is boastful and haughty, but that was not the case with Dovid Melech Yisrael: His humility was both a contrast and a complement to his kingship. His royalty was an outgrowth of his modesty. This is the unique brand of majesty that comes with true yiras Shamayim.

“The same was true of my ancestor, der heiliger Ruzhiner, zechuso yagen aleinu. The Ruzhiner was known to walk in golden shoes, but few knew that those shoes had no soles. Despite the outer grandiose appearance, his feet were wounded and bruised with every step. Once when he went out for Kiddush Levanah, those who followed him saw blood in his footprints. That was a manifestation of Dovid Hamelech’s words ‘v’libi chalal b’kirbi’ — royalty on the outside, humility inside. In fact, he attested that he never enjoyed even a hairsbreadth of the materialism offered by This World.”

As if to illustrate the point, the Rebbe speaks quietly, almost monotonously, with great restraint and ultimate control over all his senses. Ruzhin is not characterized by great displays or exclamations of enthusiasm. Every move is calculated, and every time a voice is raised, it is done with a purpose. In this chassidus, the physical is an outgrowth of the spiritual; the mind controls the heart.

But there is yet another layer of meaning to the golden trappings often associated with Ruzhin, one that the Rebbe explains with a parable: “Chassidim once asked the heiliger Ruzhiner about the preferred way to serve Hashem, and he replied with the following parable. Two brothers were sentenced to death by the king, but the king offered them both a chance to escape their sentence. He brought them to a riverbank and declared that he’d pardon whichever brother could succeed in crossing the river on foot. One of the brothers threw a long rope from one riverbank to the other. The end of the robe caught onto a tree on the banks of the opposite side, and the first side was tied near where he was standing. The man began walking along the thin rope. Masses of people witnessed the scene in wonder: The man walked confidently and reached the other side, and thus, his life was saved. People asked him how he was able to do it and he said, ‘When I felt myself leaning to the left, I leaned over to the right, and when I veered rightward, I leaned to the left, and that’s how I crossed.’

“Concluded the Ruzhiner, ‘What is the right away for a person to choose to serve Hashem? It is the middle way.’ That was his approach: the middle way, which the Rambam calls the shvil hazahav. And zahav, gold, is emblematic of royalty.”

Fusing Heart and Mind

The Sadiger Rebbe shlita — Rav Yisrael Moshe Friedman — has mastered his own fusion of influences. As a child, the Rebbe lived with his family in Crown Heights, where during the 1960s his father, Rav Avraham Yaakov Friedman, had a shul at 400 Crown Street. (Rav Avraham Yaakov’s father, Rav Mordechai Shalom — the Knesses Mordechai — was the Rebbe of Sadigura at the time, based in Tel Aviv. Upon his passing in 1979, Rav Avraham Yaakov became Rebbe and ultimately moved the court to Bnei Brak.)

When the time came for him to attend yeshivah, he traveled to Eretz Yisrael, where he merited an especially close relationship with his grandfather, the Knesses Mordechai. At the same time, he made great strides in his learning at Yeshivas Ponevezh. The Rebbe’s personality and influences might be aptly described as a combination of mizrach and maarav, a string of pearls ranging the gamut of the yeshivish and chassidic worlds.

That range of influences is still apparent in the Rebbe’s approach. His sichos are delivered in a yeshivish style and include deep pilpulim, while the Ramban, Maharal, and other early sifrei machshavah are constantly present on his table.

When the time came for him to establish a home of his own, the Rebbe married the daughter of the eminent Vizhnitzer chassid and philanthropist, Rav Chaim Moshe Feldman of London. The ties between the families had been forged years earlier, as his own father was a son-in-law of Reb Chaim Moshe’s grandfather, Reb Yosef Aryeh Feldman.

After his marriage, the Rebbe continued to learn, acquiring breadth in Shas and poskim, and received semichah from gedolei hador Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Chanoch Henoch Padwa — with whom he maintained a daily chavrusa for 18 years — Rav Yitzchak Yaakov Weiss, and Rav Shmuel HaLevi Wosner. His ties with the Shevet HaLevi remained strong until Rav Wosner’s final days.

The Rebbe eventually settled in Stamford Hill, London, where he gained a following spanning both the chassidic and litvish communities. Twenty-two years ago, that informal following became an official community: On the 3rd of Cheshvan 5754/1993, the yahrtzeit of the Ruzhiner Rebbe, he established the Ohr Yisrael kehillah in Golders Green.

Skeptics raised their eyebrows: Why would this prince of Ruzhin — himself a resident of the chassidic stronghold of Stamford Hill — start a kehillah in a neighborhood so far removed from chassidus? The answer was not long in coming: Dozens of families who traced their roots back to Ruzhin found their way to the chassidic hoif erected in this litvish bastion. With time, and under the gentle and inspiring influence of the Rebbe, many began to make changes in their own lifestyle.

Over the course of time, the Rebbe became one of London’s eminent rabbinic figures, managing to avoid all dispute and disagreement while exerting a deep impact on the city. The chareidi community in London, and beyond, learned to recognize his attributes and sterling middos, as well as his brilliance in all areas of Torah, his diligence, compassionate heart and above all, his desire to help every Jew in need of assistance, in the tradition of his ancestors.

Even now, three years after he assumed his father’s mantle and moved to Bnei Brak, the members of his London community remain very close to him. Many will not make any major decisions, financial or otherwise, without consulting him. For his part, he returns their love with an outpouring of warmth and affection. The Rebbe is moser nefesh to accompany them at every stage of their own lives, in both tragedy and joy.

The Deepest Question

On the chassidic map, it’s hard to find a phenomenon that mirrors the Ruzhiner dynasty: There have been six rebbes in succession, all of whom have perpetuated the legacy of the founder. Yet the rebbes and chassidim are still so closely intertwined with their forebearer that his name is constantly invoked and his holy influence felt. They study his Torah, share stories about him, and can still touch an item that he held or a gartel that he wore.

Here, in the Bnei Brak court, we hear a story that took place when the Ruzhiner Rebbe was six years old and his mother took him to Berditchev. (The Ruzhiner lost his father, Rav Shalom Shachna of Prohobich zy”a, at a very young age). When the Ruzhiner entered the town, Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev ordered all the residents to don their Shabbos best and welcome the holy six-year-old. The Baal HaTanya, Rav Shneur Zalman, founder of Chabad, was there for the wedding of his granddaughter to the grandson of Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev. He called the child over, and told him to ask for whatever he wished. The Ruzhiner asked about a seeming contradiction between the first two pesukim of Krias Shema: “Shema Yisrael” involves annulling oneself before the greatness of the Creator. If so, how is it possible right after that to instruct us to “love Hashem your G-d?” If one’s entire being is annulled, then how can he be commanded to love?

The Baal HaTanya later related, “I resolved his question with an explanation so deep that all the pens and ink in the world could not fully express it — and yet this holy child fully understood what I relayed.”

“It is known that the heiliger Ruzhiner didn’t have an indentation over his lips where the angel taps a baby before he is born in order that all the Torah he has learned is forgotten. The Ruzhiner Rebbe knew the entire Torah from the moment he was born.”

It’s All about Emunah

When the current Rebbe took the helm of the chassidus after the passing of his father in 2013, he brought a unique brand of leadership to the court. The Rebbe is admired by many beyond the chassidic world because of his broad familiarity with the entire spectrum of the Torah world, and because of a deep chinuch doctrine that inspires masses of young chassidim with the fundamental approach of the Ruzhiner dynasty.

“It’s impossible to describe the great esteem that the Rebbe accords those who study Torah,” chassidim relate. Since he became Rebbe, he has established new learning sessions for the chassidim, often reiterating that “the main principle of Sadigura chassidus is learning Gemara with Rashi and Tosafos.” On Simchas Torah, the Rebbe dances with the bochurim who were tested on hundreds of pages of Gemara over the past year.

But there is an emphasis on the bedrock basics as well. Sadigura chassidim relate that the Rebbe also attributes great importance to studying Chumash with Rashi, and he emphasizes that in our generation there is no greater remedy to the tests of emunah. All the bochurim fill out cards each month with a list of what they have studied in Chumash, Rashi, and Sefer Hachinuch. The Rebbe receives these cards each month, and they rest on his desk. On Friday night, when the chassidim pass by to receive a “Gut Shabbos” from the Rebbe, he can stop a chassid and ask him, “What does Rashi say on this pasuk?”

When asked to encapsulate the great chinuch challenge faced by our generation, the Rebbe returns to the basics once again — albeit adding his own take, and mention of the holy Ruzhiner, to the discussion.

“I’ll read you a piece from the Ramban,” the Rebbe begins, opening the sefer at the ready on his table, and pointing to the piece that states, “It is a mitzvas aseh to find Elokuso Yisbarach, and to know Him, as it says, ‘V’yadata hayom va’hasheivosa el levavecha.’

“What does it mean ‘to know the greatness of the Creator’?” he asks. “Only someone who learns Ramban on parshas Bereishis, which speaks about the Creation of the world, or the end of parshas Bo, about Yetzias Mitzrayim, can know the greatness of Hashem. I have instituted the practice of studying Sefer Hachinuch and Chumash with Rashi each week, because the basic condition for emunah is for a Yid to know the reasons for the mitzvos.

“I think,” the Rebbe adds, “that the weakness that we see in this generation is, regretfully, a result of the technological churban, which is fueled by the fact that Jews don’t know to affirm the basic emunah. If we offered rock-solid chinuch in emunah, with firm foundations, it would be harder for the young generation to stray from the path.”

The Rebbe goes a step further, and offers practical guidance to chinuch: “Every parent must study the fundamentals of emunah with his children, and explain to them clearly Who runs the world. And he must teach them the taamei hamitzvos — the source and reason for the commandments. When a father learns with his children the basic sifrei emunah, and explains to them the pasuk, ‘L’maan tizkor es yom tzeisecha mei’eretz Mitzrayim kol yemei chayecha,’ then he’s doing his part to ensure that his children will grow up with firm foundations that cannot be swayed by any wind in the world. The whole concept of Yetzias Mitzrayim, which we mention every day, is to imbue us with the idea that there is a Creator. But we need to instill this deep in the hearts of the young generation, so it becomes unshakeable knowledge.

“Yesterday I spoke with a person who’s dealing with a bochur whose observance has slackened. It emerged that the bochur knows nothing about emunah. He had always been told: if you don’t do the mitzvos, you’ll be punished. Of course, without ahavas Hashem and an understanding of the mitzvos, he can easily stray from the path as a result of ignorance. I gave this bochur a list of seforim to learn: Chovos Halevavos Shaar Habitachon, Maharal, and most of all, select pesukim with Rashi.”

And of course, there is a vignette about the Ruzhiner to illustrate the point. “The legendary chassid Rav Eizik of Homel was once dispatched by his Rebbe, the Tzemach Tzedek of Lubavitch, to spend a Shabbos in Ruzhin. There, the Rebbe told him, he would acquire new understandings of avodas Hashem. On Friday night, Rav Eizik participated in the tish, and the heileger Ruzhiner did not say a devar Torah. He was very surprised. At Shalosh Seudos, again, the Rebbe did not say any Torah, and again the chassid was surprised, because he was used to hearing deep divrei Torah from his Rebbe.

“On Motzaei Shabbos, Reb Eizik waited outside the heiliger Ruzhiner’s chamber to take leave of him. There was another person waiting there with him; this fellow’s job was to recount stories of tzaddikim. To the surprise of Reb Eizek — who was a respected rosh yeshivah — the Rebbe instructed that the storyteller be admitted first. The man spoke to the Ruzhiner for a long time, and only afterward was Reb Eizik admitted.

“When Reb Eizik was finally allowed in, the heiliger Ruzhiner said to him, ‘You must be wondering why I admitted him first. Let me answer with a different question. You would think that the Torah would start with the first mitzvah — hachodesh hazeh lachem. Why does it start with the story of Bereishis? Rashi explains that koach maasav higid l’amo — the bedrock foundation of all Yiddishkeit is to internalize the power of HaKadosh Baruch Hu. First we have to learn emunah in Hashem and know Who created the world. Then, when the foundations are firm, we can reach mitzvah observance. That’s why I so value the work done by the storyteller, who uses stories of tzaddikim to cement our fellow Jews’ foundations of emunah. Only after that foundation is laid can we delve into the depths of mitzvos and kiyum haTorah.’ ”

Just Two Sugar Cubes

That appreciation of deep foundations — both spiritual and physical — lends an aura of extra excitement to the Sadiger court in recent months. They are drawing closer to the conclusion of a long-awaited project, the renewed cementing of one of the foundations of the chassidus: the historic kloiz of Sadigura, initiated by the Ruzhiner Rebbe himself, and completed by his son the Alter Rebbe of Sadigura. This spiritual center of four generations — once feared lost, then miraculously rediscovered — is soon to be completely restored.

To understand just why the newly refurbished Sadiger kloiz is so important to the chassidim, consider its background.

Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin was mercilessly persecuted by the Russian Czar Nicholas I. In the spring of 1838 he was arrested on trumped-up charges, and 22 months later, he managed to escape from prison after some devoted chassidim bribed the chief warden.

It was crucial that he leave Russia, but the ensuing journey was filled with challenges and difficulties. Finally in 1842 he managed to find a safe refuge — the village of Sadigura, in the Bukovina region, then under the sovereignty of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Rebbe’s chassidim purchased a plot of land for him, and he gained Austrian citizenship, which saved him from the murderous designs of the Russians.

When the Rebbe left Russia, he brought several precious items along. With every border crossing or other danger encountered along the way, he had to forgo yet another item. There was one thing he refused to forgo, however: a case containing the architectural plans for his future beis medrash. The Rebbe himself had sketched out these plans, in keeping with lofty intentions and exalted kavanos.

It’s said that Rav Moshe Tzvi of Savran once expressed his difficulty comprehending the show of majesty associated with the Ruzhiner court. In response, the Oheiv Yisrael of Apt told him to visit the court, after which he’d understand everything. When he arrived, the Rebbe took him to a private room, where he opened a drawer and showed him two cubes of sugar. “One is for me, one for my rebbetzin,” the Ruzhiner Rebbe told his visitor. “This is our entire Olam Hazeh.”

Then the Ruzhiner took his guest to another chamber. “Let me show you something,” he said, and led Rav Moshe Tzvi to a locked case, covered with carvings and engravings. The Rebbe opened the case and took out a sheaf of blueprints — the precious plans for his future kloiz. The Savraner Rebbe, who understood the spiritual significance of the blueprints, entreated the Rebbe to refrain from actualizing them; he recognized their source as lying in the blueprints of the Mishkan and feared that the world was not spiritually prepared for the erection of such a holy edifice.

But the Ruzhiner Rebbe persisted in his vision and in 1847, five years after he arrived, construction work commenced. But he passed away in 1850, before his plans were completed. The kloiz was ultimately completed by his son, the first Sadiger Rebbe.

The kloiz was the pride of the entire chassidus; in fact, the Sadiger archives hold a document signed by those original chassidim who took part in its construction. By any standard, it was considered a magnificent architectural work. The southwestern wall held the “davening shtiebel,” the private room where the rebbes would isolate themselves for prayer. The walls of the room were decorated with murals of various holy sites in Eretz Yisrael.

Four generations of Sadiger rebbes led their courts from this unique kloiz until the onset of World War I. At that point the larger Czernowitz region became the scene of many bloody battles, and the Knesses Mordechai, who was Rebbe at the time, was forced to escape from Sadigura just two years after assuming the mantle of leadership. He spent the interim period between the two world wars leading the chassidus from Vienna. In 1933, he moved to Poland, and then in 1939, he settled in Eretz Yisrael.

Despite the Odds

For many years, a heavy fog surrounded the fate of the kloiz, but the previous Rebbe harbored a constant dream to locate and restore the building. The Rebbe spent most of his tenure living on Pinkas Street in Tel Aviv, right near the embassies of several countries. The Rebbe would send trusted chassidim to those embassies that had some connection or relationship with the USSR and enlist their help. But the USSR denied the existence of Sadigura, claiming the entire village was a ruin. Later, chassidim located official NASA aerial images attesting that the village was still extant. Later still, the current Rebbe obtained photos of the kloiz from Chaim Kaufman, a chassid and Belgian resident who had managed to arrange a covert visit to the area.

Amazingly enough, the building had survived — enduring two world wars, aerial bombing, conquests and various sovereigns, the breakup of the Soviet Union and subsequent instability. (A year ago, a historian tracked down a photo of the kloiz dating back to the World War II era. This photo depicts the flags of the Red Cross affixed to the side of the building. Apparently, it was used as some sort of headquarters by the Red Cross, which spared it from bombing — unlike the hoif, the personal living quarters of the rebbes, which did not survive.)

The next stage would be to restore the kloiz to its former grandeur. But that vision would not be easily realized.

“This was during the Soviet era,” the Rebbe explains. “We weren’t even sure we could get permission to enter the country. But with the help of a few askanim, a trip was arranged. When the time came, my father arrived in London, where he spent Shabbos with us. On Sunday, we flew to Sweden, and from there to Moscow, and from there on a third flight to Lviv [Lemberg], from where we traveled to Sadigura.

“When we arrived in Sadigura,” the Rebbe recalls, “we first traveled to the holy resting place of the heiliger Ruzhiner and the following three generations of Sadiger rebbes. When we arrived at the tziyun, the look on my father’s face was of utter fear.

“Then we continued to the kloiz. When my father saw it standing intact, his tears flowed copiously. We entered the building and saw that the heichal was now a tank and tractor factory. However, perhaps it was because of this that the site survived — because had there been no factory, it was likely that the non-Jews would have destroyed it. Still, it was a scene of much heartbreak.”

The previous Rebbe was to travel to Sadigura six times in all. He didn’t merit to see the completion of the restoration of the kloiz, but he set the process in motion. Sadiger chassidim note that just like the first Rebbe completed the kloiz based upon the planning of his father, the Ruzhiner Rebbe, so too, the Rebbe shlita, is completing the building that his father initiated and planned. But it was far from a simple task.

First, the chassidim fell victim to the former mayor, when they asked him to arrange an official purchase of the kloiz. The fellow instead extorted a huge sum of money in exchange for a meaningless piece of paper. But the previous Rebbe would not give up. He urged the present Rebbe to utilize his contacts in London and other locations, and try once again to officially purchase the plot.

The real restoration work began on the 3rd of Cheshvan 5761 (November 2000), the yahrtzeit of the Ruzhiner Rebbe. The previous Sadiger Rebbe made a special trip to the burial site of his ancestor, and instructed his gabbaim to pack up all the kvittlach he’d received before Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur because, he said, “All the Yamim Noraim tefillos go through here.”

During that trip, an ohel was constructed over the graves of the Ruzhiner Rebbe and those of his descendants (chassidim dismantled the original ohel at the onset of World War II, fearing it would draw the attention and ire of the Nazis).

While restoring the kloiz was a long-term goal, the threat to the cemetery was immediate. A local school situated nearby was planning to build a sports complex. The chassidim knew they had to save the cemetery, and so they applied for administrative rights as an official Jewish community.

Then the ohel began to sink into the ground. The Rebbe instructed the chassidim to build a proper ohel, with full access and elevated walkways to avoid stepping over other graves. This would also allow Kohanim access, since the Ruzhiner Rebbe had requested to be buried at the side of the cemetery so Kohanim could also daven at his gravesite.

With the cemetery’s future more certain, the chassidim were able to turn their attention back to the kloiz.

“I’m Building This for You”

The current foreman of the restoration project is a local contractor named Moshe Kreiz. Kreiz was born in Czernowitz to a Jewish family and maintains a strong sense of Jewish identity, but knows little about his heritage — the sad result of decades of disconnect. When the previous Rebbe visited the village, Kreiz greeted him personally; he’d learned that it’s proper to ask the tzaddik for a blessing and since he planned to run in the mayoral elections in Czernowitz, he asked the Rebbe to bless him with a victory at the polls.

“You’d be better off abandoning the idea,” the Rebbe told him. “You won’t get elected in any case. Any time you need salvation, you can visit the gravesite of the tzaddik and you will be saved. If you help me, Hashem will help you.”

At the time, Kreiz wasn’t sure how he could possibly help the Rebbe. But the words made a deep impression.

“A few years ago,” the project supervisors report, “we announced a tender for the second phase of the restoration project. One of the people who applied for the job was Moshe Kreiz. His estimate was the best, and he had lots of experience, so we chose him for the job.

“One day he called us, obviously very moved, and told us in juicy Yiddish, ‘Don’t ask what happened. A few days ago we found a crack along the length of one of the towers on the building’s exterior. I immediately evacuated all the workers, as there was a real danger that the building would collapse. Then I brought down some expert architects for advice. They all agreed that the tower was about to collapse, maybe even taking down the entire left wing of the building with it. There was no way to reinforce it — it has to be removed entirely.

“ ‘Then I remembered what the Rebbe had told me — that if I need a yeshuah, I should daven at the tzaddik’s gravesite. So I went there and screamed, Heiliger tzaddik, I’m not building this house for myself — I’m building it for you. So please, take care of the problem. Tehillim I can’t say, but Yiddish I speak, and the tzaddik understands it too. I spoke to him in Yiddish — and he understood! When I returned to the building site, the architects told me that the tower had suddenly stabilized sufficiently for them to reinforce it.’ ”

That wasn’t the only surprise they encountered. One of the most heartening episodes was the discovery of the ancient Ruzhiner mikveh, excavated at the instruction of the previous Rebbe. This is an especially deep bor which had been filled with refuse over the years. It is currently being emptied so the original mikveh of groundwater can be restored. It is said that the Ruzhiner Rebbe himself would immerse in this mikveh.

Along with the mikveh, the workers also located a stamp more than a century old. When they stamped a paper with it, everyone recognized the result: the trademark insignia of the historic Sadigura kloiz — copies of which are preserved in several seforim that were smuggled out of the kloiz during World War I. The discovery was an exciting one, and the stamp is currently housed in the court’s archives.

Until Mashiach

Several prominent Sadiger chassidim are involved in the construction effort, under the direction of Rav Mordechai Shalom Yosef Friedman, the oldest son of the Rebbe, who is in charge of this project along with many other spiritual tasks in the Sadigura court. Rav Mordechai Shalom Yosef, who was extremely close to his grandfather, tells how his grandfather use to often ask him whether his passport was current — he wanted to be sure that he would be available at the soonest possible moment to travel to Sadigura.

In addition to the chassidim who plan to travel there, some ten thousand Jews currently live in the Sadigura area itself. The restored kloiz stands to provide many opportunities for kiruv once the site is functional.

But since the building is a registered historic site, there are tight restrictions surrounding the project. Renowned architect Aaron Ostreicher drew up the restoration plans in cooperation with the University of Lviv and interacted with the local antiquities authority to obtain the necessary permits.

The financial patron of the restoration project is the legendary Shmuel (Sami) Rohr z”l, himself a descendant of a family of Ruzhiner chassidim, who passed away in 2012. Rohr felt a deep connection to the Ruzhiner court, taking a strong interest in this development. He sang Sadiger melodies at his Shabbos table. While he was widely known for his largesse toward Chabad shluchim, he saw the restoration of the Sadiger kloiz as the closure of a family circle. His son, Yekusiel Yehuda (George) Rohr, has taken responsibility for perpetuating his father’s work and is still involved in the project.

As it grows closer to completion, hundreds of chassidim are making plans to join the Rebbe’s journey back to the restored kloiz, scheduled for Cheshvan.

“The kloiz is a remarkable structure,” the Rebbe says. “One of the unbelievable architectural innovations is the fact that there isn’t a single pillar or beam inside at all. It’s very spacious with a heavy ceiling — yet there isn’t a single support beam. Even with our advanced architecture it’s not easy to plan something like that.”

In fact, the engineer who drew the original plans for the building during the previous Rebbe’s time was brought especially from Italy. But in Ruzhin, the supernatural explanation will always supersede the natural explanation:

“The heiliger Ruzhiner planned this kloiz,” the Rebbe says. “He infused lofty kavanos in the planning, channeling the same spiritual forces used in the building of the Mishkan. But he was unable to build it himself, just as Dovid Hamelech did not merit to build the Beis Hamikdash, and it was completed by his son, Shlomo. So, too, here, the Ruzhiner planned it and the Sadiger Rebbe built it.

“The world says that the reason the Ruzhiner Rebbe was imprisoned was because he was slandered by the maskilim. But the truth is that it was a struggle between the forces of holiness and those of the netherworld. The same reason spurred the Ruzhiner to invest so much energy into purchasing the land in the Old City of Yerushalayim that would eventually house the Tiferes Yisrael shul. He was struggling against the emissaries of the Czar, who wanted to build a church there on that site. The Ruzhiner knew that this was not about physical, temporal buildings: it was a battle between the forces of holiness and the Sitra Achra.

”In the end, the Czar’s emissaries failed, and after the Rebbe’s chassidim bought the site, the Czar was forced to find someplace outside the Old City walls. Today you might know the site as the Russian Compound.”

Is the battle still ongoing? Is history replaying itself in the current construction effort that’s taking place in Sadigura? The Rebbe evades a direct response, but from his answer it it’s clear that the restoration of the Sadigura kloiz is not just about a physical building.

“This is a makom she’hispallelu bo avoisai, a place where my fathers davened, and the intense kedushah that was poured into its foundations sanctified it for generations,” he says. “B’ezras Hashem, we will soon merit the arrival of Mashiach and then the batei knessios of Bavel will be moved to Eretz Yisrael. I am sure that the Sadiger kloiz will be on the Eastern wall of batei knessios in Eretz Yisrael.” —

Timeless Majesty

5602 / 1842 – Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin reaches a safe haven in the Austrian Empire after years of Russian persecution, settling in Sadigura and receiving Austrian citizenship.

5607 / 1847 – Under his direction, chassidim of the Rebbe begin building the magnificent kloiz, following blueprints personally sketched by the Rebbe.

5611 / 1850 – Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin is niftar on 3 Cheshvan. His eldest son, Rav Shalom Yosef Friedman, is appointed in his stead, but is niftar 11 months later. Rav Avraham Yaakov Friedman, the second son, called the “Alter Rebbe,” begins serving in Sadigura as the first Sadiger Rebbe.

5643 / 1883 – The Alter Rebbe is niftar on 11 Elul. His son, Rav Yisrael, known as the Ohr Yisrael, takes his place.

5667 / 1906 – The Ohr Yisrael is niftar on 13 Tishrei. His son, Rav Aharon, known as the Kedushas Aharon, takes his place.

5673/ 1912 – on 19 Tishrei, after just six years at the helm of the chassidus, the Keduhas Aharon is niftar. Like his predecessors, he was laid to rest in the ohel of his ancestor, the Ruzhiner Rebbe. His son, Rav Mordechai Shalom Yosef, known as the Knesses Mordechai, takes his place.

5674 / 1914 – World War I breaks out. A few weeks later, the Knesses Mordechai flees to Vienna, where he joins the other rebbes of the Ruzhiner dynasty.

5678 / 1918 – Rav Avraham Yaakov Friedman of Sadigura, who would become known as the Ikvei Abirim, is born on 5 Elul in Vienna.

5693 / 1933 – The Knesses Mordechai makes his first visit to Eretz Yisrael.

5699 / 1939 – in Adar, the Knesses Mordechai makes his second visit to Eretz Yisrael, deciding to settle there permanently. Later, in Sivan, his wife and son will join him. The Rebbe establishes his court on 10 Betzalel Yaffe Street in Tel Aviv.

5732 / 1972 – the Knesses Mordechai moves his court to the beis medrash on 41 Pinkas Street in Tel Aviv.

5739 / 1979 – the Knesses Mordechai participates in the wedding of his grandson — the only son of the Ikvei Abirim, current Rebbe of Sadigura. The wedding takes place on 19 Teves. Three months later, on 29 Nissan, the Rebbe is niftar. He was laid to rest in the Nachlas Yitzchak cemetery in Givatayim. His son, Rav Avraham Yaakov, known as the Ikvei Abirim, takes his place.

5765 / 2005 — The Ikvei Abirim moves his beis medrash to Gutmacher Street in Bnei Brak.

5773 / 2013 — the morning of the 19th of Teves, at 7:30 a.m., Rav Avraham Yaakov is suddenly niftar, to the shock of chassidim across the globe. He is buried in the Nachlas Yitzchak cemetery alongside his father. His son, the current Rebbe, takes his place as the seventh rebbe in the dynasty, as well as his father’s role in the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudas Yisrael.

Under the leadership of the current Rebbe, the chassidus has continued to blossom. The Rebbe has emphasized Torah learning and instilling emunah in the next generation, through the study of Chumash and Rashi, Sefer Hachinuch, and other fundamental texts.

The court’s two major centers are located in Bnei Brak and Yerushalayim, and include chadarim, yeshivos, and kollelim, numbering more than 1,000 talmidim. Additional communities exist in Ashdod, Beitar, Modiin Illit, Beit Shemesh, and Tzfas, along with the original nucleus in Tel Aviv. Outside of Eretz Yisrael, Sadigura counts faithful adherents in New York and London, where the Rebbe lived until he took his father’s place. Another beis medrash is currently under construction in Lakewood, New Jersey.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 613)

Oops! We could not locate your form.