Educate Your Child According to His Way

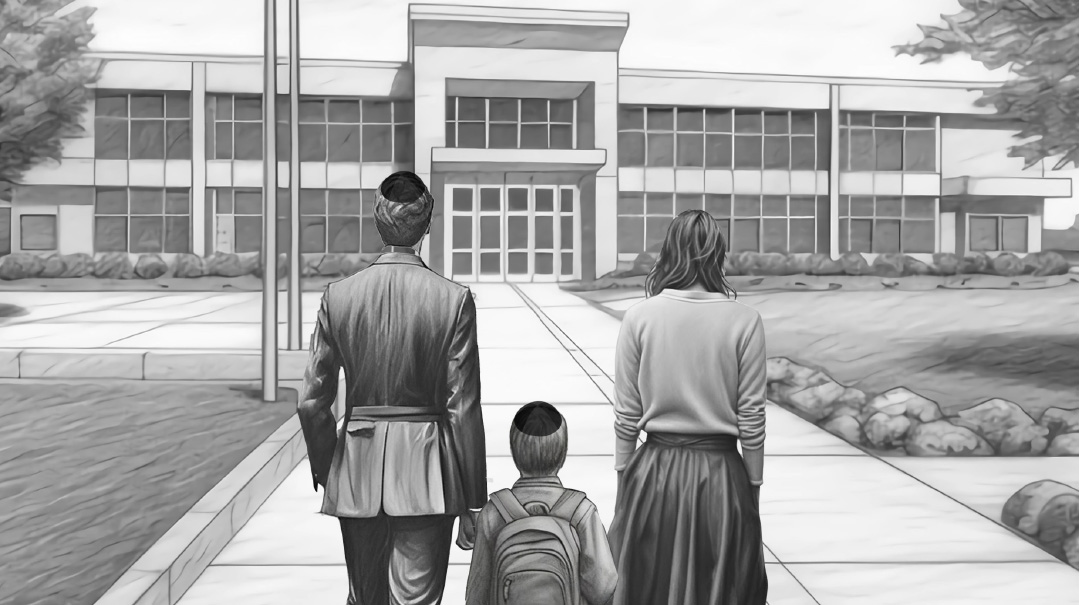

| June 13, 2023Four mothers speak about stepping outside of the frum bubble to meet their child’s unique educational needs

When a child has special educational needs that cannot be met within the framework of a frum school, parents are faced with what seems like an impossible choice:

Do they leave their child in a trusted environment but watch the daily struggle erode his self-esteem?

Or do they send him to a specialized school where he’ll get the tools he needs, but will be exposed to a secular worldview?

Even after parents have asked daas Torah and are assured that switching schools is the right choice, it’s still not an easy path. Four mothers speak about stepping outside of the frum bubble to meet their child’s unique educational needs.

ELISHEVA’S STORY

“My son Dovid attended frum schools in Chicago through part of high school, but had some behaviors that concerned us,” Elisheva remembers. Academics weren’t challenging for Dovid, but picking up on and following social cues was. He was overly rigid, yet clueless about scheduled school events even when they were announced frequently. He also had trouble planning ahead.

His transition to high school wasn’t smooth. “He was never in the right place at the right time. During assemblies, he’d be in the hallway, or he’d be outside when he was supposed to be inside,” recalls Elisheva. He wanted to keep every chumra, and he also tried to be everyone’s mashgiach.

They started sending Dovid to a therapist and tried all sorts of incentives, charts, checklists, and behavioral techniques to help him do the right things at the right times. They arranged for special time with grandparents, cousins, and friends. They took him for educational therapy to work with him on organization and executive functioning. It was incredibly intense, but at the same time, it wasn’t enough.

Finally, his rebbi told them, “He needs something that he can’t get here.” Dovid was a solid learner, and was doing fine academically, but it was clear that he needed more guidance in learning how to follow societal expectations.

“A big part of this challenge was the guilt,” shares Elisheva. “The feeling of not being a good parent. I would ask myself, ‘Why is my kid different from the others? What could we have done differently?’”

Their therapist told them about a nonpublic school that could help their son develop the skills he was missing. The state of Illinois has a number of these private, nonsectarian, state-certified schools that provide special education services to students based on their Individualized Education Plan (IEP).

Elisheva started doing research. Most of the students who attended the school were not frum or not Jewish, but Elisheva knew people in her community who had sent their children there. She spoke to the mothers, so it wasn’t a complete unknown. She and her husband were impressed when they visited the campus and spoke with the administration. By the time they went to ask a sh’eilah, they were comfortable with the idea of sending Dovid to the specialized school.

“We knew it was highly structured, that it could help our son become a more confident person and achieve success socially,” says Elisheva.

He attended the NPS until early afternoon, then went to second seder at his yeshivah, followed by dinner at home and night seder. It wasn’t a secret that he was attending a secular school, but Elisheva didn’t discuss it, except for with close friends. If it came up in conversation, she kept it vague, mentioning that he was temporarily going somewhere else, but not sharing more details than that.

For support, she turned to other students’ parents, as well as a therapist, who helped her talk through the experience. “I was figuring it out as I went along and taking advice from professionals. You have to try, and you must keep an open mind. I wasn’t sure what was going to work and what wasn’t, but I kept trying.”

Elisheva acknowledges that sending a child during their impressionable teenage years into a secular environment is a risk, and many children can pick up unrefined language or behaviors. Dovid was unique in that he didn’t feel pressured to fit in with the secular environment. He kept his yeshivish levush and didn’t socialize with his classmates at the NPS. “I think it was due to a combination of his personality and already established religious convictions, plus a lot of mazel, zechusim and tefillah,” she says.

While it’s normal for parents to be nervous about sending their child to a secular school, Elisheva and her husband felt strongly that self-esteem is the foundation for success. “As teenagers, it’s so hard in general. For him it was even tougher because he had these extra struggles. Sending him to that school helped him get himself together, find himself, and then he was able to move forward. For us, it was no choice. And baruch Hashem, we had daas Torah guiding us.”

After graduating high school, Dovid joined a small beis medrash and then attended a frum college, where he was very focused and did well. He is now married with a family of his own.

Looking back, Elisheva can see that Dovid was, and still is, his own person. “Everyone is different,” she says. “But if we learn how to follow the basic rules of society, we can go off and be who we want to be and create our own lives.”

SORI’S STORY

At the age of three, Sori’s daughter Zeesi had very delayed speech. She was so hard to understand that Sori made explanation cards for Zeesi’s morahs so they would know what her daughter was saying. This was one of the first signs that Zeesi might have some developmental challenges. But even as a baby, there were clues. “She just cried and cried,” remembers Sori. “If I had known what the future held, I would’ve cried along with her.”

Zeesi’s kindergarten year was the Covid year, and while the school offered to provide reading help, it wasn’t realistic to do that over Zoom. By first grade, she was behind, but so was everyone else. When Sori first brought up her concerns to the school, she was told to wait until after midterm testing, when her daughter qualified for Title 1 services.

Because of Sori’s experience as an interventionist, she knew that the school services wouldn’t be enough to fill in the gaps. Her daughter needed more support. “If I had ended up in nursing school instead of special education, I never would have known that she had this challenge. Hashem saved us.”

They took Zeesi for a neuropsych evaluation and started the process of figuring out how to help her.

Sori discovered that a number of frum families in her out-of-town community sent their children to a local private school that specializes in language-based learning disabilities. So she started making calls, speaking to parents who had students currently enrolled, as well as those who sent in the past. “Both the parents and the students themselves told me it was the best thing they’d ever done,” Sori remembers.

While they were contemplating this switch, Sori attended an event at a local high school and heard a beautiful speech from a girl who had attended the specialized school and later reintegrated back into the frum school. Sori was filled with hope. She thought, That could be my daughter, too.

They asked daas Torah if placing their daughter in this school was the right decision, and they were told yes, but that they should speak with the rav every summer and reassess for the coming year.

“My other children were nervous about their sister going to a non-Jewish school. How would they explain it to their friends? But everyone was so understanding.”

There are currently five frum children in Zeesi’s carpool, so there is peer support, even if the other frum students are not in Zeesi’s classroom. Teachers know to be careful about kashrus and will text parents pictures of candy to make sure it’s acceptable. The school has also put filters on the browsers, and will tell the parents when it’s “hot cocoa day” so parents can send in chalav Yisrael hot cocoa.

While the school environment is wonderfully supportive, it’s still hard that Zeesi isn’t in a school with frum peers, admits Sori. Situations come up that require guidance from their rav, like whether to wear a costume at the school Halloween party.

Zeesi is the only one wearing tzniyusdig clothes in her class of eight, so a good family friend gave her a book about tzniyus, Proud to Be a Princess, by Genendel Krohn. “I don’t know if I would have bought that book for my other children,” says Sori. “They didn’t need it. We try to think of the things she’s facing and help her. We must pump in the pride and excitement more than normal. Baruch Hashem, my daughter doesn’t really express a desire to fit in. She does play nicely with her peers at school, but she knows this school is for helping her read, but it’s not her ‘real’ school and friends.”

As far as navigating the tricky piece of how to be friendly but not friends with her classmates, Sori relates that it’s not such an issue. Some students travel up to two hours to get to school, and as the students are spread apart geographically, there is zero expectation that friendships will develop outside of school.

To maintain a social connection with her daughter’s frum peers, Sori makes sure that her home is a fun place to be. “For Zeesi’s sake, we have Sunday clubs. We put a water slide in the backyard so all the kids in the neighborhood want to be here. I go above and beyond to make sure she’s socializing with frum girls. Also, when the frum school does something special, whenever possible, we’ll take Zeesi out of private school so she can attend.”

It will be almost three years in the school, and Sori is hoping that this coming year will be the last one, and that she’ll be able to transition her daughter back to the day school her other children attend.

Sori has worked hard to maintain a connection to the day school for Zeesi. “The school sends home contests, charts, and siyum treats for her. And whenever the private school has days off, which is relatively frequently, Zeesi goes to the day school with her sisters. She has a uniform, a locker, and a classroom.

“The principals are amazing,” says Sori. “They are always telling us, ‘She’s our student, she’s our girl, we can’t wait to see her here!’”

BASHY’S STORY

Eighteen years ago, when Bashy’s daughter Dassy was born with Down syndrome, the options for special education in frum schools in the Tristate area were nonexistent. When her daughter was 18 months old and it was time to choose a program to send her to, Bashy chose to send Dassy to a public school program.

“I had very high expectations of what I wanted for her,” Bashy says. “I wanted her to be in a self-contained class in a regular school. I wasn’t looking to put her in a truly special ed school.”

Bashy wanted her daughter to have the experience of walking into a regular school, seeing regular behavior in the hallway, to see the dynamics of the teachers and principals. At that time, the public school was the only one that could provide Dassy with both the services she needed, and the school atmosphere and structure her mother wanted.

For Bashy, it wasn’t a question of non-Jewish or Jewish, but rather, where are the educational resources available for this population? “The psak I got from my rabbanim was that our first job is to make her into a functional person, and then take care of her Yiddishkeit.”

Dassy did occasionally have Jewish classmates, and sometimes there would be some kind of Jewish staff, but for the most part, she was the only Jew in her environment.

“It wasn’t my first choice to put my daughter in public school, but it wasn’t like, ‘Oh, no, this isn’t something I can do,’’’ says Bashy, who grew up in Europe and attended a Jewish school where there were many levels of observance. “I come from a family of rabbanim, and we were always taught to respect and tolerate everyone around us, even as we knew that we had to be different. My parents had very high expectations of us, and we knew we couldn’t do everything our friends were doing.

“Still, it’s hard when you know every morning that you’re sending your daughter to a school full of non-Jews. No one singing Modeh Ani with her, no one saying brachos with her.” To give her daughter a taste of Yiddishkeit, Bashy devoted time and resources, hiring private tutors to come every single day to her house to teach her the alef-beis and daven with her.

While Dassy went to public school to get the skills she needed, the rest of the time she was surrounded by a loving family. She had the balance of going to school for school’s sake, but she didn’t participate in any of the after-school programs. “Even in the summer, most of the years I declined the summer help, and I put her in a regular Yiddishe day camp,” says Bashy.

Because of the growing number of Jewish students with Down syndrome who needed services provided by public school, a bilingual classroom was opened within the school Dassy attended around six years ago. It is a Yiddish/English-speaking classroom, and the makeup of the class is only Jewish children and Jewish staff.

Dassy no longer attends that school. Bashy’s dream from so many years ago has come true, and Dassy is finishing school in a self-contained classroom in a regular frum school. Because of the services she got through public schools all those years, she has the skills to be a mensch, and because of the devotion of her family, plus siyata d’Shmaya, her connection to Yiddishkeit is still strong.

YAFFA’S STORY

When Yaffa’s son Yonah was in nursery, he was very quiet. By kindergarten, it was clear he wasn’t understanding things at school. At one point, his parents stopped asking him parshah questions at the Shabbos table. “He couldn’t even tell us the stories, couldn’t answer the questions,” Yaffa recalls. “It was confusing — he was a bright boy, so why wasn’t he able to give over these basic concepts?”

Yaffa was a preschool teacher, and she would make excuses for his baffling behavior. She said to herself, “Okay, so maybe he’s a late bloomer. He’s gonna get it sooner or later.” She thought it would just click, like she’d seen with some of her students.

The school suggested that Yonah repeat kindergarten, but Yaffa didn’t want to do it. “He’s so on the ball, he’s so self-aware, he’s gonna see that his friends are going ahead and he’s staying put.” So, they decided to advance him to pre-1A.

But a few months into the school year, Yaffa was getting calls from the rebbi. “I don’t know why, but when we ask questions, he doesn’t get the concepts,” he told her. Kriah was a problem, too. Yonah could read the letter and he could identify the nekudah, but he couldn’t put them together. The school told her they thought her son had a reading issue and suggested that he get evaluated.

Yaffa turned to Dr. Malky Zacharowicz, a frum psychologist known for doing thorough neuropsych evaluations. Dr. Zacharowicz identified some red flags for dyslexia and confirmed that Yonah had a language-based learning issue and some processing issues as well. She recommended taking him out of the yeshivah and putting him into a school that specializes in remediating students’ dyslexia or other language-based learning disabilities.

Yonah got wait-listed at the school of their choice, so Yaffa placed him in a transition school where he stayed for two years. It was a school that takes in kids with dyslexia, language-processing challenges, and some social issues as well. They have speech and occupational therapists on staff, and the teachers are all special ed teachers. “They give your child a lot of the skills they need to move forward,” says Yaffa.

But they still needed to find a school that could properly teach their son. After doing research, they narrowed down the choices to two schools — a nonreligious one and a non-Jewish one — and turned to a rav to figure out the best option.

For second grade, they switched Yonah to Shefa, a pluralistic Jewish school for children with language-based learning disabilities in Midtown Manhattan. Until two years ago, they couldn’t get busing, so Yaffa and her husband would drive Yonah to and from their home in Far Rockaway. Without traffic, it took about 45 minutes. With traffic, it could be two and a half hours.

Even though it was a long commute, Yaffa appreciated the amount of alone time she got with her son, and when he finally got busing, she was sad to lose that built-in quality time.

Because Shefa is a pluralistic school, that means there are all types of Jews who attend and work there, but the school is accommodating to the religious needs of the parents. “When we went to orientation for new parents, they told us that there’s a rule that students aren’t allowed to share snacks because of kashrus. And if someone makes a birthday party, they need to first ask all the parents in the class what level of kashrus they need,” says Yaffa.

The first day Yonah got home from school at Shefa, even after the long commute, he wanted to do his homework. “I was blown away,” says Yaffa. “Kids who struggle don’t want to do homework. Kids that feel successful have no problem doing their homework. He does his homework all the time. There are no questions asked.”

This doesn’t mean it’s easy. Because he doesn’t retain material very well, Yaffa works very hard to help him study, giving him hints, reminding him what he learned, and testing him again and again. “I have to work hard, and I’ll do it,” she says. “But sometimes I’m ready to explode, and I have to walk out of the room.”

They allow his friends from school to come to their house, but before they let him go to any of his school friends’ homes, they do shidduch-level research into what kind of home it is. They’ll speak to neighbors, even the rebbetzin of the shul. “We try to protect him as best as we can, but at the same time, I firmly believe that hashkafah comes from the home.”

Even though Yaffa never imagined sending her child to a school with such a diverse population, she is glad she did. “When your child is in yeshivah or Bais Yaakov and not thriving, they can resist Yiddishkeit because they associate the school with religion,” explains Yaffa. “I would rather my child attend a school with a different hashkafah from mine, davening three times a day and loving Hashem, than taking a different path or hating himself so much that he turns to self-medicating.

“He feels his confidence. Happiness breeds success. He has friends, he’s a somebody. That’s so very important for his Yiddishkeit.”

*Names have been changed

Dos & Don’ts

There’s a right — and wrong — way to respond when you find out someone switched their child to a non-frum school.

Do:

Remember this child at Purim, at class simchahs (bar/bas mitzvahs), and group events like birthday parties.

Include the child in the social scene, for Shabbos playdates or a local game of ball.

Greet the child warmly when you see him out during school hours — they may have very different days off.

Take the parents’ lead on how to describe the situation to your own children.

Be supportive. Give the parents chizuk if they are opening up to you about their feelings or a particularly challenging experience.

Talk to the child positively — “Wow, your new classroom sounds fun! Tell me about it!”

Don’t:

Be nosy. If someone is giving you vague responses, take the hint.

Drop the child as a friend just because they switched schools.

Assume this decision was made lightly.

Ask if they got eitzah from a rav.

Recommend other special schools. Understand that if they want your input, they will ask for it.

Ask the child when they’re coming back to school.

Advice and chizuk from parents who’ve been there:

“You really need to go with emunah. Your child is Hashem’s child also. You just do your best.”

“Try to make friends with at least one of the moms who is familiar with your child’s school. It will help you navigate your way through.”

“Remind yourself often: You don’t owe anyone an explanation for your decision.”

“Find activities within the frum community that work for your child. My public school daughter enjoyed Bnos and now she’s an assistant Bnos leader.”

“The most important advice is to be 100 percent on top of the food situation. Find out at the beginning of the year what type of food is given in the classroom and send a substitution.”

“Mark your calendar Erev everything to call absences into both the school and the bus!”

“Explain to the teacher right away that Saturday is a day that you’re never available. Public schools sometimes do family events on Saturday. It’s much better to tell them up-front that you can’t do it, rather than have them think you’re not interested.”

“My son didn’t have morahs, so one unexpected benefit was that I was the one to teach him Shema and brachos. I think that’s a huge positive. We take it for granted and leave it up to the morah and forget that we are the parent — al titosh Toras imecha — don’t abandon your mother’s Torah!”

“We have to remember that even though it’s hard, we are doing it so that our child can ultimately be a better person and hence a better Jew.”

Not so happy endings

Bracha, who lives in a small out-of-town community, switched her daughter to public school in ninth grade.

Her daughter, Ahuva, has dyslexia but also an IQ that is high enough to qualify her as gifted, and she reads way above her grade level. “As you can imagine,” says Bracha, “our school had no idea what to do with her. Aside from the learning disabilities, my daughter is quirky and spunky. She was constantly getting negative feedback.”

Bracha tried to work with the school — she even involved a world-renowned pediatric psychologist. But the school remained an unsupportive environment.

“I really think we could have made a go of it at the Bais Yaakov, since the principal here is fairly accommodating, but by the time we got to that stage, Ahuva wasn’t doing well. At that point, we just had to take her out.”

After the initial relief of being out of a damaging environment wore off, reality set in. “I think Ahuva thought public school was going to be a utopia,” says Bracha. “She thought everyone there would be so wonderful and accepting. Then she got there, and she realized that, no, there are mean kids everywhere.”

Now Ahuva is in 11th grade, and she told Bracha a few weeks ago that she thinks she acted a bit hastily. “But it’s hard to walk that back.

“I wish we had people in this community who understood learning differences, and that we had the resources as a community to deal with these kids. Pulling kids out for learning centers isn’t really fixing the problem. I wish we had teachers who knew how to meet kids where they are.”

A lifeline for parents

“We must not fail in our responsibility to teach all children,” says Dr. Malky Zacharowicz, a sought-after psychologist and assistant professor at Touro University. She is is known for her comprehensive evaluations and for providing support to parents who need to leave the frum velt to better educate their children. “Chanoch l’naar al pi darko is not just a slogan. It’s an imperative.”

When Dr. Zacharowicz opened her private practice in the Five Towns, after years of working with the general population, she didn’t know how much of a need there would be for her services. “But it was eye-opening,” she says. “There was such a need. Some kids were drowning in their schools.”

Children would come to her for evaluations because of behavioral and emotional issues, and then, through testing, she would uncover the layers, and at the bottom of the behavior was an undiagnosed and untreated learning disability. The children were dysregulated after years of anxiety from being in a situation where they couldn’t thrive.

“These kids are suffering,” says Dr. Zacharowicz. “And by extension, their parents are suffering, their family is suffering. And it’s not a negative reflection on the teacher. These are general ed teachers — they have mandates as to what they must cover in the curriculum and at what pace. But these children need to be taught in a different way, which extends beyond a few times a week or a day in a resource room. When these kids are sent back into the mainstream classroom, they still don’t know what to do. It’s not a matter of them just trying harder.”

When a student is diagnosed with a learning disability, his parents may choose to apply for an IEP (Individualized Education Plan), a document that outlines special education services a child must receive. If a child doesn’t qualify for an IEP, she might qualify for a 504 plan. These plans will outline modifications that may help the child in the classroom, such as working with fewer items per line, having instructions read aloud, answering test questions verbally, or having more time to complete a task.

While some children may be able to succeed in their schools with this support, Dr. Zacharowicz stresses that there is a tremendous difference between modification and remediation. With modification, a child is given a more manageable amount of work. Remediation, by contrast, teaches a child the skills to learn independently.

A child can have modifications for years, and then they’ll get to a point in their educational experience where they won’t have the skills that they need, which creates a bigger problem. Additionally, the unintended consequence or implied message that a child receives with modification is, “You can’t do it,” as opposed to, “Let’s learn the strategies.”

In some cases, struggling children may need to attend a specialized school for a few years to obtain the skills they need to return to a mainstream environment. Once these children are sent to a school that understands their unique needs, the relief is palpable. It’s both normalizing and destigmatizing.

“One mother told me that when her son was in yeshivah, they would give him a soda to make him feel good,” Dr. Zacharowicz recalls. “Her son’s response was, ‘I don’t need the soda.’ Once he switched to a different school, he was happy to wake up at the crack of dawn for the long commute because he felt safe. People understood how to teach him, and there were other children like him who had similar needs.”

Dr. Zacharowicz acknowledges that while many children are saved by going to specialized schools, there are no guarantees. “Can there be negative outcomes? Absolutely. But do we necessarily know that it would’ve been better if they had stayed in the Jewish frameworks?”

When asked how she helps parents weather the storm of being in a non-frum school, Dr. Zacharowicz points out that often the challenge of reintegration is harder. “Some kids don’t want to come back because they don’t want to feel anxious or misunderstood again.

“I tell parents, imagine if you went to work every day but you didn’t have the skills to accomplish the tasks. You’d feel miserable. The same applies to your child: Every day they face assignments they don’t have the skills to tackle. They’re sitting in a classroom and every day they’re told off, they’re kicked out, they’re not successful.”

How do you rebuild that? Slowly and with a lot of siyata d’Shmaya. “Now, more than ever, we must double down on our efforts to keep the kids feeling like there’s a community for them, and that they’re valued. They should feel valued. Because if they don’t get it from us and from their day-to-day experiences, they’ll look for it elsewhere.”

While most of the children she evaluates can stay in their schools, some require a short stint in a special education setting. Over the years, Dr. Zacharowicz has consulted with rabbanim and has recommended schools such as the Gesher School, Gesher Yehuda, Pathways, the Sinai School, PTACH, and CAHAL, along with highly specialized schools that focus exclusively on a cohort of neurotypical children with language-based learning disabilities like the Windward School or the Shefa School.

More recently, the frum community has taken up the mantle to create schools of excellence within our community to service children with language-based learning disabilities. This past year, Shalshelet, an Orthodox school for children with language-based learning disabilities, opened in New Jersey. A similar school is being considered for Baltimore.

This fall, in Belle Harbor, a new school called Torah Academy for Language will be opening. Equidistant from the Five Towns and Brooklyn, TAL aims to be a dual-curriculum yeshivah of excellence. It is designed to help build a foundation of strong language and literacy skills with reading and kriah specialists, language pathologists, special ed teachers, occupational therapists, and properly trained morahs and rebbis.

For children who require highly specialized remediation, these schools provide a lifeline.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 847)

Oops! We could not locate your form.