Drink L’Chayim to Life

| January 7, 2025Surviving six death camps, Yosef Lewkowicz touched the lives of thousands and kept reinventing his own

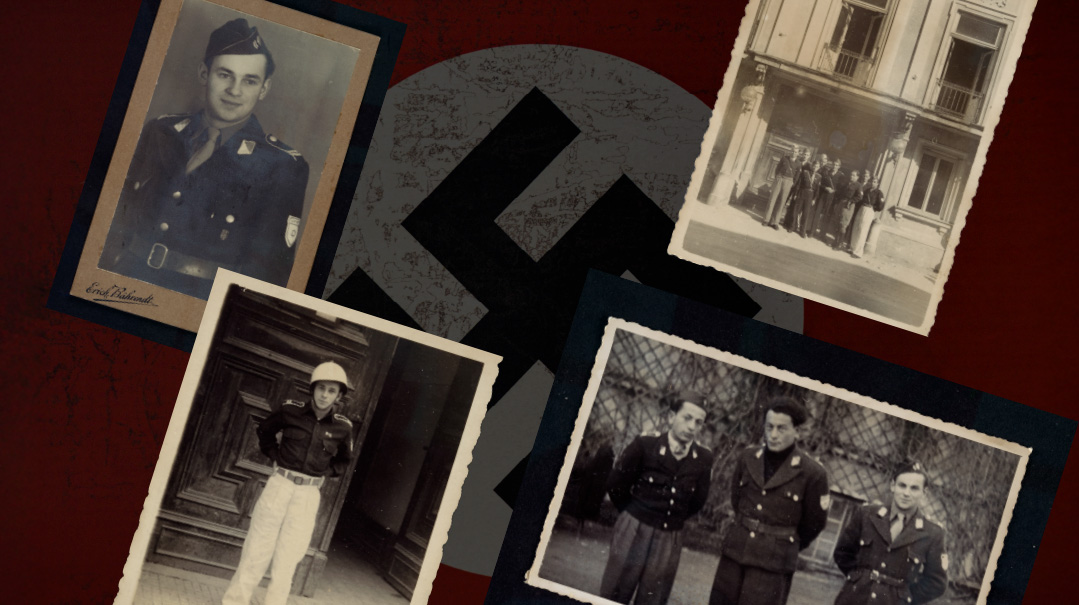

Photos: JRoots– Joseph Lewkowicz archives

Yosef Lewkowicz, who passed away on Chanukah at age 98 and was one of the last adult witnesses to the Holocaust, kept reinventing his life. After surviving six labor and death camps, he became a Nazi hunter, went on to build a family in South America and Canada, and then, at 88, restarted again in Jerusalem and touched the lives of thousands on trips back to Poland, as he urged an unabashed recommitment to authentic Yiddishkeit

When Reb Yosef Lewkowics was niftar on the second night of Chanukah at the age of 98, the Jewish People lost one of the last adult witnesses to the Holocaust. Lucid and articulate until his last days, Reb Yosef was a living testament to the unimaginable atrocities for a generation both distanced by time and plagued by doubts as to the very truth of the Holocaust narrative. And his mission wasn’t only to pass on a historic account, but to strengthen eternal Jewish values that are the only real guarantee of ongoing survival against the odds.

Reb Yosef, who moved from Montreal to Jerusalem’s Arzei Habirah neighborhood ten years ago after his wife passed away, was the only surviving member of his large family, most of whom were murdered in the Belzec death camp in 1942. He spent the last stage of his life testifying to all he went through and witnessed — something he sublimated for years until his adult children encouraged him to open those old wounds. And then, he was unstoppable.

Within the framework of my own 30-year-long project to capture the spiritual legacy of survivors, I’ve spent countless hours interviewing, filming, and redacting Reb Yosef’s experiences, values, and life lessons. I had the privilege of introducing him to our JRoots tours, thereby opening Reb Yosef’s persona to thousands of people — young and old, frum and secular — in addition to facilitating dozens of press interviews and TV appearances (with both Jewish and non-Jewish journalists). His story and persona were so compelling that we decided to bring it to international publication in book and documentary form. Both the book, The Survivor: How I Survived Six Concentration Camps and Became a Nazi Hunter (translated into 12 languages) and the documentary, The Survivor’s Revenge have met with huge interest and reader/viewer popularity.

Reb Yosef, who was still an excellent communicator with a remarkable memory and driven energy well into his late 90s, lived through six years of forced labor and concentration camps. Born in the village of Dzialoszyce, Galicia, and then moving with his family to the epicenter of Jewish Krakow at the age of eight, he was bar-mitzvah age when the full force of the Holocaust changed his life forever. His ordeal included the brutality of Plaszow, Auschwitz, Mielec, Amstetten, Mauthausen, and Ebensee.

Reb Yosef’s father, Simcha Lewkowicz Hy”d owned a mill in Dzialoszyce, while his mother, Sheindel Hy”d, ran the family store. When we traveled back there to visit his home, he pointed out exactly where he raced down the hill on his new tricycle and where he fell in the stream by his father’s mill. While we stood outside the desolate ruins of the shul, he showed us where he sat with his father and brothers and recalled the fragrant challah rolls his mother would bake each week for their family and for needy people who came by.

While we were standing outside his childhood home, he suddenly recalled the song Reb Koppel, his cheder rebbe, taught them, sharing with us a Yiddish niggun he learned over 90 years ago: “Eretz Yisrael mein teyere land/ Oif di gantze velt bis du doch bakant (“Eretz Yisrael my precious land, throughout the whole world you are renowned)…” Since then, whenever we returned from leading a group of students to Poland, as soon as Eretz Yisrael came into view from the plane window, he would sing this niggun.

In 1935, the family moved to the Kazimierz district of Krakow so that young Yosef could learn in the Talmud Torah. The next few years he lived on the corner of Lewkowa Street, just two doors away from the famous Rema shul. Today, that building houses the local police station.

Many JRoots groups to Poland have stood there with Reb Yosef as he’d point to the street sign that is indeed his family name, then listening to his description of Lag B’Omer, the yahrtzeit of the Rema, whose shul and kever are just a stone’s throw away. He would describe the throngs of Yidden who would fill the town square right in front of his home.

Around this time, Reb Yosef became attracted to Bobover chassidus, drawn in by the derech avodah of simchah and tefillah. He vividly described the enchantment of Bobov and of the thrill of traveling to the Rebbe, the Kedushas Tzion. Reb Yosef was himself an accomplished baal tefillah, and until just a few months ago, every Shabbos Mevarchim he would lead Bircas Hachodesh in his Arzei Habirah shtibel.

At the beginning of the war, Reb Yosef found himself part of a labor detail assigned by the invading Nazis to plough over the old Jeruzolimska Jewish cemetery in order to build the infamous Plaszow forced labor and concentration camp. He described the massive earth movers he was forced to walk behind with a wheelbarrow, collecting remains of the dead ploughed up by those monster machines. At that point, he didn’t realize it, but he and his father were already the only survivors of his family (his father was later murdered in Plaszow).

In Plaszow, Yosef managed to gain favor with the head kapo, Wilek Chilowicz, who would sometimes give Yosef a little extra food in exchange for shining his boots. Chilowicz would actually save his life from the hands of the infamous “Butcher of Plaszow,” Amon Goeth.

Goeth was the camp’s commandant, infamous for his brutality and random murder sprees. Reb Yosef said that Goeth would kill people for looking him in the eye, or for walking too slowly. On one occasion, Reb Yosef remembered, Goeth pulled a prisoner named Shlomo Spielman out of a lineup, said in German, “I cannot take it that that Jew looks so handsome,” and put a few bullets into him on the spot.

Reb Yosef himself came close to being killed by Goeth in Plaszow. On a work detail one day, he was perched at the top of a column whose bricks and ironware were to be dismantled and shipped back to fuel the German war effort. Goeth came by with his two huge killer dogs and watched as Yosef dropped a dislodged brick down to his friend, to be placed in a wheelbarrow. Seeing Goeth and the dogs there, his friend got so nervous that he dropped the brick. Goeth immediately drew his gun and shot the fellow, then ordered Yosef down from the column. Reciting Shema as he followed orders, Yosef saw Goeth brandish his revolver to finish him off.

Reb Yosef had no memory of what happened next, but what he did remember is that he woke up a few days later covered in cuts and bruises. Chilowicz, it turned out, saved the teenager by beating him unconscious and then having his limp body dragged away, telling Goeth, “Save your bullet, he’s already dead.”

While we were filming for the documentary together in the lush country park that was once Plaszow, we actually stumbled upon the foundations of those columns. I cleared away the leaves and lifted up a brick from deep in the grass. I asked Reb Yosef if he wanted a souvenir. He said, “Naftuli, one day perhaps you’ll make a museum and tell our story — and then tell them about the power of a Shema!”

ITwas a sweltering hot summer day when we were filming, and I was worried that Reb Yosef would get sunstroke so I suggested we take a break. But he would have none of it. “Naftuli,” he admonished me, “we’re here to work. We have a job to do. Let’s keep going!”

And so, we crisscrossed Poland and Austria at a speed that would exhaust a much younger person. As we traveled from place to place, he would often recall niggunim from the heim, or begin to hum Bobover nusach that he’d be reminded of.

We stood together at the foot of the infamous “186 Stairs of Death” by the Wiener Graben quarry at Mauthausen concentration camp. He gazed in disbelief at the cruelty and torture he both experienced and witnessed at that very spot. He described how the starved, emaciated, and bedraggled inmates were forced to carry huge rocks on their backs up the steps. Steps that he had witnessed being awash with the blood of the innocent who would inevitably topple over in exhaustion, causing a cascade of human skeletons to tumble down behind them, crushing more and more as they fell.

I don’t think I ever saw Yosef Lewkowicz get annoyed or frustrated — he was the calmest of men, despite everything he went through — but as we stood there, Reb Yosef bent down, picked up a rock, and threw it full force at those accursed steps.

An hour later, we stood inside the camp of Mauthausen, peering out over the quarry. I asked him if there was anything his parents taught him that kept him going through six years of sheer brutality and depravation. He said that his mother taught him a phrase in Polish: “Na grzecznowski nikt nie traci — be nice, be fine, be polite, be a mensch, and you’ll never lose.” (Even today, his children Ziggy and Sheila can rattle it off in Polish.)

Reb Yosef was 19 when he was liberated at the Ebensee concentration camp in Northern Austria in May 1945. While we were filming together in 2019, Reb Yosef made the brachah, “She’asah li neis bamakom hazeh” next to the gate of the camp.

After having ascertained that there were no survivors of his large family, and having been threatened by neighbors on return to his home in Krakow, Reb Yosef resolved never to return and instead devoted the year following the war focusing on two incredible and heroic missions while based at the DP camp in Bad Ischl in Austria.

His first mission was to act on a piece of information his father had told him six years before — that many Jewish toddlers were being handed over for safe keeping to non-Jewish families in the hope that their chances of survival would be greater, and with an agreement that the parents would return and retrieve them after the war if they survived. Most never returned. Reb Yosef, multilingual with honed negotiating skills, was determined to find as many of these lost Jewish children as possible.

Working via the Jewish Agency in Paris together with Dr. Yitzchak Refael and Eliezer Unger, and with the blessing of Chief Rabbi Yitzchak Herzog, he painstakingly identified and repatriated 600 Jewish children, bringing them to a central rehabilitation center from where they traveled to Italy and then on to Palestine. This is an untold story of heroism, for which Yosef Lewkowicz was never truly recognized. At some point, his children suggested he look up those war orphans and remeet them, but he said he wasn’t interested. He was truly humble, never felt like he deserved the credit, and it was a very difficult period for him. He told his family at the time that he preferred to put it behind him.

His second project when the war ended was to work with the US military police in order to track down some of the major SS officers, who were hoping to disappear among the mass of regular Wehrmacht soldiers. He was a good candidate for the mission, as over the last six years, he’d had firsthand encounters with some of the Nazis the Allies were trying to find.

Working out of the DP camp in Bad Ischl, he painstakingly searched for months. There were six primary people on his list, including Mielec commandants Julius Ludolf and Otto Streigel, Mauthausen’s Johannes Grimm, Ebensee “hospital” director Hans Kreindl… and Amon Goeth.

He knew that Goeth had been arrested, so he set about combing the prison camps in search of him. At a prison camp at Dachau, only months after the war ended, a soldier directed him to the man he was looking for. And then, for the second time, he came face-to-face with Amon Goeth.

“When I saw him,” Reb Yosef related in several media interviews we’d arranged, “he was lying on the ground, on the dirt, dressed like a beggar, half of his former size. I recognized him right away. I would know that murderer’s face anywhere.”

Reb Yosef said that when people heard the story of how he found Goeth in that prison camp, they asked him why he didn’t just shoot him there and then. “Shooting him would have given him a gold medal,” Reb Yosef said. “He deserved to suffer more.”

In fact, Reb Yosef actually visited Goeth in his cell and tried to engage him in conversation.

“I sat next to him and said, ‘Amon, tell me, why did you do this? Who asked you to do it? Tell me. It’s just the two of us here…’ Truthfully, it was very humiliating for me to do that, but I wanted to know if Goeth felt any remorse. But he didn’t respond, didn’t even acknowledge my presence. It was clear to me that he would have done it again,” Reb Yosef said.

Goeth was tried for war crimes in Poland and sentenced to death. He was hanged in September 1946, not far from the site of the Płaszow camp.

Reb Yosef took particular satisfaction in noting a point of Hashgachah that only he would know. He related that when Goeth was finally sentenced to death by hanging, the noose broke and he had to be hanged again. It’s a very unusual occurrence, one actually limited by international law. But he told of an incident he personally witnessed in 1943 when a Jewish camp inmate named Kanner had been caught concealing a piece of chicken. As a punishment and lesson for all, the camp was ordered to the Appelplatz to view the hanging of this criminal. But the first attempt to hang him failed, as the noose broke. According to international law such an incident would require clemency, yet the Butcher of Plaszow himself lost no time in delivering two deadly shots himself to Kanner’s head. The irony of Goeth’s own demise was not lost upon Reb Yosef.

I was present on many occasions when reporters and journalists would ask him about revenge. And he’d tell them that his greatest revenge was not behaving as his oppressors did, but building an observant Jewish family and supporting the rebirth of Jewish education. That’s the main reason we called the documentary The Survivor’s Revenge. People hear of his heroic hunt for Nazis and are drawn to that story, but for Reb Yosef, his greatest revenge was not ever to stoop to the level of the sonei Yisrael and instead to remain devoted to Torah, to Klal Yisrael, and to Eretz Yisrael.

Despite his desire to go to Eretz Yisrael after the war, Yosef yearned to connect with any family member he could possibly locate in the world. He found a cousin in Argentina and decided to stay in South America, eventually marrying Perla Lederman, settling in Colombia, and building a successful diamond business that had him traveling all over the world. Two of their children, Ziggy and Sheindel, were born in Colombia, and their third, Tuvia, was born in Montreal.

For decades, Yosef Lewkowicz — although a pillar of his community wherever he lived — refused to speak about his Holocaust experiences.

“I wanted to forget. I didn’t want to look back. I just wanted to look at the future because the past was terrible, fearful, demoralizing,” he said. He even had a plastic surgeon remove the number on his arm, which he later regretted. Later in life, once he became a public face of the Holocaust, it would have been a symbol of resilience.

His adult children urged him to share his story, and he had occasionally spoken over the years, but JRoots really gave him an opportunity to become a living conduit for personal Holocaust history.

Reb Yosef finally realized his dream of living in Jerusalem in 2014, several years after his wife passed away when he made aliyah on his own at the age of 88. Years earlier he had been one of four investors having had the vision to erect the first four buildings that would eventually form the thriving neighborhood of Arzei Habirah today. But at the time, there was a devaluation of the shekel and the investors lost their money. Reb Yosef would often talk about the deals he missed in business, but would always say that, just as he weathered the raging tempest of the Holocaust, the nisyonos he endured throughout his lifetime — even those that were purely monetary — actually helped bolster his unwavering faith in the Ribbono shel Olam.

In his later years, he became very close with Rav Yosef Efrati, the rav of Arzei Habirah. Among his regular Shabbos and Yom Tov hosts were Rav Efrati, “Senters” Rosh Yeshivah Rav Chaim Zvi Senter and his family, his chavrusa Rav Shlomo Paley, and Machon Yaakov’s Rav Yosef Lynn, whose children adopted Reb Yosef as their “zeide.” Rav Efrati would say of Reb Yosef that he had two malachim who protected him throughout the Holocaust: One to save his physical life and one to ensure his emunah remained intact. He basked in the opportunity to daven three times a day at the minyan just downstairs, attend daily shiurim and somehow catch up in the learning and avodas Hashem that he’d missed out on for a chunk of years.

Just when life seemed to settle, tragedy struck again, when in October 2021 Reb Yosef’s son Tuvia was hit by a car on his way to Selichos in New Jersey. Once again Reb Yosef’s reservoirs of bitachon were tested to the limit, but somehow, he bounced back and continued sharing his incredible life story with the thousands of young Jews worldwide who gained so much from him.

At the levayah, my JRoots partner Zvi Sperber spoke of how, when Reb Yosef would accompany us on our trips to Poland, he would knock on Reb Yosef’s door to wake him up, only to find him fully dressed at 6 a.m. reciting Tehillim. Even when he became very sick in recent months, he would constantly inquire about the list of those in need of tefillos whose names he kept in his well-worn siddur. He remembered all the names of women davening for children, of those in need of shidduchim or a refuah. While most people his age are consumed with their own health issues and other worries. Reb Yosef stood out in his genuine care for others — it never changed since those early days after the war when he turned over every stone to rescue hundreds of Jewish children.

Over the years, I’ve had the privilege of interviewing hundreds of frum survivors, but Reb Yosef was truly remarkable among them. His zest for life was infectious, his emunah palpable, and his ability to both share his remarkable story and to communicate authentic Yiddiskeit produced a very tight bond with the groups who had the privilege to travel with him to Poland and to the camps.

He loved a shtikel herring and a l’chayim, and whenever I visited him, the ritual was the same. “Naftuli, before we talk, we must make a l’chayim!” I mention this because for me Reb Yosef Lewkowicz’s l’chayim was no regular “cheers!” His l’chayim resonated with the ultimate survivor’s revenge — of seeing doros yesharim living and learning Torah, especially in Jerusalem. He was pained by the scourge of assimilation, and was always happy to address student groups organized by Aish HaTorah, Machon Yaakov, Senters, and others, sharing with them a passionate, unabashed commitment to Torah and mitzvos and their relevance in the modern world.

Just a few short months ago, Reb Yosef became paralyzed from the chest down, diagnosed with a terminal illness. When the diagnosis came in, the first thing he said to me was, “Naftuli, we’ve done some good things together, but we’ve only just started. Promise me you’ll continue! So many young Jews just don’t know who they are. We must teach them. We must show them. You must keep going. L’chayim!”

Yehi zichro baruch.

Rabbi Naftali Schiff is the founder of Jewish Futures family of educational organizations. He is co-founder and director of JRoots, which specializes in facilitating educational journeys to places around the world that carry a Jewish story, and is the primary provider of frum trips to Poland for the English-speaking world.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1044)

Oops! We could not locate your form.