“Dos Yiddishe Hartz”

| December 31, 2024My experiences with Mordechai Strigler carry a moral lesson from which one can learn something valuable

Title: “Dos Yiddishe Hartz”

Location: New York City

Time: May 1998

Writers’ Note

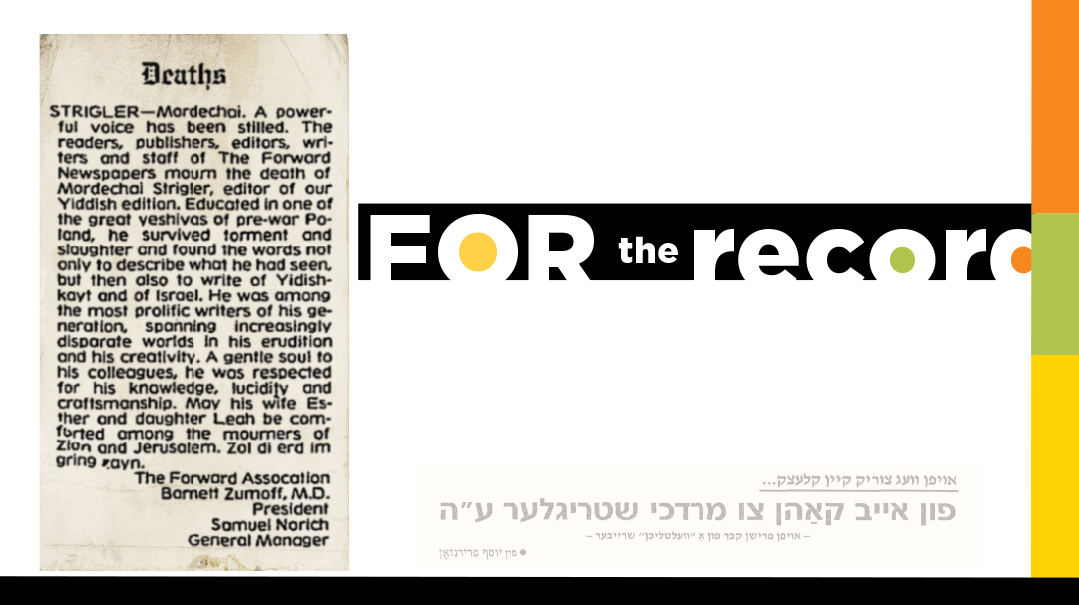

Last week’s For The Record, titled “The Finnish False Messiah,” included excerpts from an article written by the Yiddish journalist Mordechai Strigler. We received an email from a reader who asked if we had ever delved into Strigler’s background, because his story would surely be of interest. Additionally, we were pointed to an exceptional tribute to Strigler following his 1998 death, penned by Reb Yosef Friedenson, the noted editor of Agudath Israel of America’s Yiddish magazine, Dos Yiddishe Vort. We found it extremely moving and decided to share it with our readers this week in full.

(Our additions appear in a different font.)

At the Fresh Grave of a “Worldly” Writer

By Yosef Friedenson

I imagine that not a single one of our readers will, upon reading the title of this article, refrain from raising their eyebrows and wonder: Since when does Dos Yiddishe Vort write obituaries about prominent secular writers?

I have a response for this.

First and foremost, this relates to a personal feeling. We were friends, “companions in suffering,” or “brothers in adversity,” during our time in Buchenwald. There, he strengthened me, and I owe him a debt of gratitude — hakaras hatov, a core Jewish value. He earned my acknowledgment and, as is customary among Jews, a few words of praise.

But what relevance does this have to Dos Yiddishe Vort? After all, Dos Yiddishe Vort doesn’t belong to its editor, but to the Orthodox community. Did he merit recognition from this community?

My answer is that, despite all reservations about secular writers, Mordechai Strigler, of blessed memory, had many merits, some of which were public and worthy of acknowledgment. Moreover, I want to emphasize that when I use the term “secular” in relation to him, I do so with quotation marks, because his “secularism” never entirely overtook him. To some degree, a spark always remained from his younger years, when he studied in Novardok and Kletzk. While he unfortunately drifted far from Kletzk, Kletzk never entirely left him. This, too, is a merit in my eyes.

Moreover, my experiences with Mordechai Strigler carry a moral lesson from which one can learn something valuable.

I first met Mordechai Strigler in Buchenwald by chance. Next to my barrack, Block 67, was the so-called “Youth Block,” Block 66, where the Germans had crammed several hundred youths. I went there to visit my close friend, Reb Dov Kahan from Munich, who is now a prominent Gerrer philanthropist and a longtime friend of our journal. There, to my astonishment, I encountered a historical-literary lecture by Mordechai Strigler.

Mordechai Strigler was born in the Polish town of Stabrow, on the outskirts of Zamosc, where his father was a farmer. The historic community of Zamosc perfectly illustrated the diversity of Polish Jewry; it was home to Rav Yaakov Kranz, the Dubno Maggid, and the famed Yiddish writer Y.L. Peretz, among others.

Strigler grew up in a chassidic family and went to study in the great Lithuanian yeshivos, including Novardok and Kletzk. He later settled in Warsaw, serving as a teacher in the Great Synagogue on Tlomackie Street and as an assistant to Rav Tzvi Yechezkel Michelson.

When the Nazis invaded Poland, Strigler initially joined a partisan group. As the Germans closed in on them, he tried to escape to Russia, but was arrested by German soldiers at the border. The soldiers tortured him, carving swastikas into his cheeks and forehead. Somehow, he escaped death.

He would go on to endure various ghettos and concentration camps under inhumane conditions, among them the notorious Majdanek outside Lublin, from which there were few Jewish survivors, and Skarzysko-Kamienna, which had horrid working conditions.

At the latter camp, he was interned with Rav Yitzchak Shmuel Eliyahu Finkler, the Radoshytzer Rebbe, who didn’t survive the war. Strigler was finally liberated by the US military at Buchenwald in the last days of the war.

You might wonder: “A lecture in Buchenwald?” Yes, indeed. The internal administration of Buchenwald was, as is known, controlled by leftist intellectuals, later known as the Buchenwald “Underground.” Their leaders sought to morally uplift the youth and thus organized concerts, performances, and lectures every Sunday (when the Germans indulged themselves). One of these lectures was delivered by Mordechai Strigler.

(In Saving Children: Diary of a Buchenwald Survivor and Rescuer, author Jack Werber shares his memories.)

We were sometimes able to arrange for the roll call in the “Small Camp” to be held indoors, which meant that the youngsters were not exposed to the terrible cold and snow in the winter. The challenge for us was to keep them alive, mentally and spiritually. Because of the terrible things they had seen, the children were no longer childlike.

Our group, therefore, decided to set up a school for them, but we had to convince the Underground not to oppose our efforts. We identified people whom we felt we could approach to teach the children. We explained to them that this was dangerous work and they could lose their lives if they were caught.

Mordechai Strigler, later editor of the Yiddish Forward, gave the children hope by telling them stories of Jewish resistance and courage in the past, and promising them that one day, they would have revenge against their tormentors.

During the lecture, which Strigler delivered in Yiddish, it quickly became evident to me that he must have been a former ben Torah. He used phrases and expressions rooted in sacred language, not typical of worldly intellectuals.

When I approached and introduced myself, he immediately recognized who I was. The name “Friedenson” was very familiar to him. After all, before becoming a reader of Bialik and Leyvik, he had read Der Yiddisher Tagblatt and Agudah publications. And so, we became friends. Despite his worldly nature, his girsa d’yankusa (the Torah learning of his youth) always gave us more to talk about than with the secular intellectuals.

It so happened that, a few weeks after liberation, we were moved from the barracks to more spacious quarters in former SS officers’ buildings. He, I, and two others shared a room. Living together brought us closer, especially since I was ill, and he took it upon himself to help me. In return, I “repaid” him by becoming the “guardian” of his manuscripts, as he had begun writing shortly after liberation. Within weeks, he had amassed piles of writings.

His first publication came almost immediately after his liberation from Buchenwald by the US army on April 11, 1945. He edited and wrote for the first DP journal, Tchias Hamesim (Resurrection of the Dead), which was published for the first time on May 4, 1945, in Buchenwald, in a handwritten format.

The first issue begins with strong words of encouragement, a theme that he maintained in his writings: “Don’t think that you are only survivors. You are not broken gravestones on the unknown graves, but the young seeds in the field in which a new people will be resurrected.”

We were together for only a few weeks. I, still unwell, was sent to a hospital, while he left for Paris. We didn’t meet again until 1954, when he arrived in America. Here, he became the editor of Der Yiddisher Kemfer. [He would later serve in a dual role as the editor of the Forverts –Ed.]

We often met at the printing house of the Schulsinger Brothers, where both our journals were printed. We rekindled our friendship somewhat — but only somewhat. After all, he was the editor of a Poalei Zion publication and a “disciple” of David Ben-Gurion, while I was the editor of an Agudah newspaper.

Inevitably, whenever we met, debates would ensue, and at times, we even clashed. It was no longer Buchenwald, where a bitter fate had united us. It was New York, with opposing ideals and convictions, hardly conducive to close friendship.

Over time, however, we learned to tolerate each other. We came to terms with the fact that we would never convince one another and ceased our arguments. This mutual tolerance deepened as I came to respect his knowledge and scholarship. My admiration grew further when he discovered — and almost envied — that I was a frequent visitor to the home of Rav Aharon Kotler, of blessed memory.

Whenever we met at the printing house, he would ask how Rav Aharon was doing, and I could never understand why this interested him. He also inquired about the Rebbetzin, the daughter, and Rav Shneur. Eventually, he confided in me that not only had he studied in Kletzk, but he had been a ben bayis (resident guest) in Rav Aharon’s home for nearly a year. This occurred when he arrived in Kletzk mid-term, and Rav Aharon, after evaluating him, decided not to let him leave. After difficulties arose with finding accommodations, Rav Aharon took him into his home.

This made an indelible impression on Strigler. Merely mentioning Rav Aharon’s name would evoke in him a profound reverence.

When I urged him to visit Rav Aharon, he always demurred. Finally, he admitted: “Rav Aharon will surely ask me about my Yiddishkeit. I won’t dare lie to him, but I also can’t bear to disappoint him — or the Rebbetzin.”

So, I stopped pressing him. However, I later learned that he established a quiet connection with Rav Shneur, with whom he had been friendly in Kletzk.

It turns out that Mordechai Strigler did return to see his former rebbi. In 1956, Strigler described a visit to Beth Medrash Govoha, while attending a convention in Lakewood, in glowing terms:

It is remarkable: across from our hotel in Lakewood stands a yeshivah transplanted here from scholarly Lithuania. I visited there due to a certain sentimental connection (being myself a former student of such a place), but other colleagues also went and saw: On the podium stood the aged genius and rosh yeshivah, who had delivered shiurim 40 years ago in Slutsk.

He was still passionately discussing the same [Maseches] Yevamos and singing his chiddushim with the same Lithuanian melody as in years past, as if time had forever stood still in that place. Strikingly, his listeners consisted almost entirely of American-born young men. And let me add that to comprehend such a shiur, one must first spend many years on the yeshivah bench. The entire environment — the slanted shtenders, the bookshelves, the resonant melody — bears witness to the fact that no concessions were made on their end.

So how has he managed to attract American youth without the slightest compromise? Perhaps it is precisely because of this? It may be that the American-born Jew who seeks something requires a complete sense of greatness to follow. He needs something to fill himself with, to be proud of, and he knows that mountains do not bend.

Despite his secular leanings, his connection to Yiddishkeit was evident in his writings for Der Yiddisher Kemfer, especially on Jewish holidays. His essays, while sometimes influenced by modern thought, were infused with a profound respect for Chazal and Jewish tradition.

Strigler’s love for Jewish tradition also manifested in his personal life. When it came time for him to marry, he sought the counsel of the Bluzhever Rebbe, who discreetly became his advisor. I believe the Bluzhever Rebbe even officiated at his wedding. (He maintained a close relationship with the Bluzhever and other Rebbes.)

To conclude, Mordechai Strigler never fully abandoned his Jewish roots. His Kletzk upbringing left an indelible mark, as did the values instilled in him by his parents. Even in his later years, the spirit of Kletzk was alive within him.

May his memory be a blessing.

Yehuda Geberer is a historian and tour guide of Jewish historical sites in Europe and Israel, and is the host of the Jewish History Soundbites podcast.

Dovi Safier is a business professional who enjoys researching unexplored chapters of Jewish history, with a primary focus on the yeshivos of the interwar period.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1943)

Oops! We could not locate your form.