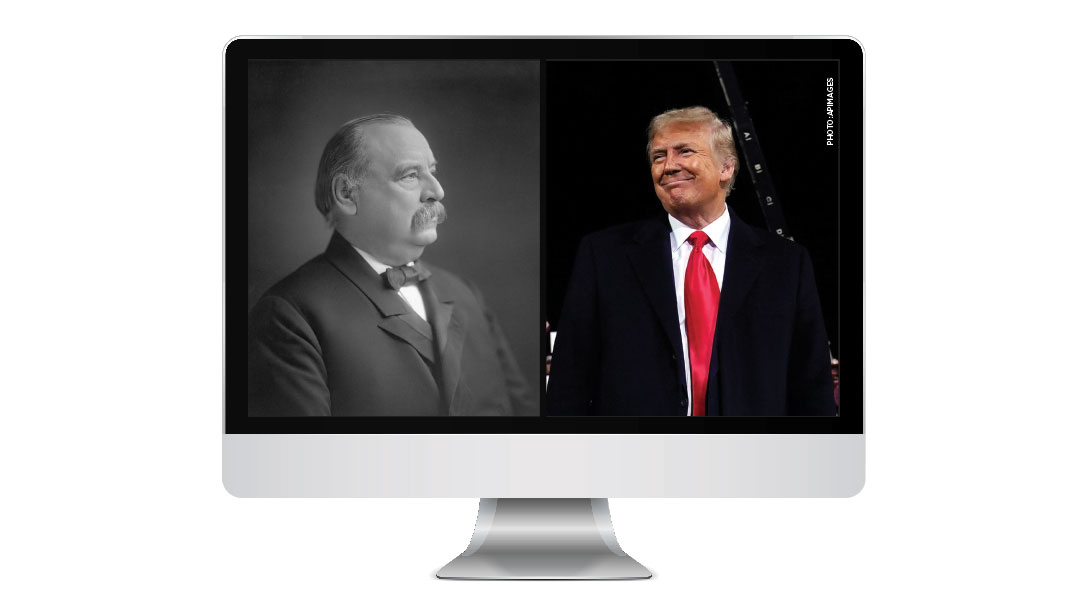

Does History Favor a Trump Comeback?

Trump does have some history in his corner in a bid for a second, nonconsecutive term

To paraphrase Richard Nixon, President Trump is making it “perfectly clear” he expects to serve a second White House term. Trump might just have to wait until 2024.

The Electoral College is scheduled Monday to formalize Joe Biden’s victory unless Trump’s legal team can quickly muster the incontrovertible proof of the massive voter fraud they allege but have so far failed to produce to the satisfaction of any court.

Some news reports suggest Trump, ever the showman, will rain on Biden’s Inauguration Day parade, announcing his 2024 presidential candidacy that same day.

Trump does have some history in his corner in a bid for a second, nonconsecutive term.

Grover Cleveland, who served as America’s 22nd president from 1885 to 1889, lost his reelection bid but returned four years later in 1893 as America’s 24th president.

Certain parallels between Trump and Cleveland are striking.

Cleveland, like Trump, overcame the stain of personal scandal to capture the presidency. Cleveland also believed he fell victim to voter fraud. And like Trump, Cleveland stood tall for the interests of the Jewish People at a critical junction in history when Jewish immigrants were pouring into the United States and rebuilding the Jewish yishuv in Eretz Yisrael.

Early in his first term, Cleveland fired the US consul to Jerusalem, Selah Merrill, an anti-Semitic cleric hostile to the growing Jewish yishuv, ultimately replacing him with Henry Gillman, a Jew from Michigan, who spoke Hebrew and Arabic.

Gillman was a staunch supporter of the yishuv, battling efforts by the Ottoman rulers in Istanbul to expel Jews from Jerusalem. Gillman persuaded Cleveland to appoint Oscar Straus to head the US mission in Istanbul. Oscar’s brothers, Isidore and Nathan, eventually bought out Macy’s. The city of Netanya is named after Nathan Straus, as is Rechov Straus near Jerusalem’s city center.

Cleveland’s presidency coincided with a wave of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe, following some 200 pogroms against Jewish communities in the Russian Empire after the assassination of Tzar Alexander II. Jewish immigration to America quadrupled during the 1880s compared to the 1870s, joining a massive wave of more than 5 million immigrants seeking a new and safer home in the US.

Facing growing calls to crack down on immigration, Cleveland vetoed a bill in his second term that called for new immigrants to pass a literacy test, saying US immigration policy, while “guarding US interests,” should be based on immigrants’ “physical and moral soundness and a willingness and ability to work,” a position resembling the merit-based immigration policy Trump hoped to introduce.

Votes for Sale

But perhaps the most striking parallel between Cleveland and Trump is the issue of voter fraud.

The 2020 election is not the first contentious race in US history. It’s the fifth, according to Dr. Robert Speel, associate professor of political science at Penn State, citing the elections of 1876, 1888, 1960, and 2000. In each case, the losing candidate and party dealt with the disputed results differently.

The 1888 election pitted Cleveland, a Democrat, running for reelection against Republican Benjamin Harrison.

If you think there are question marks swirling around automated voting machines and mail-in ballots, let’s go back in time and check out how Americans voted in the Gilded Age.

Political parties printed their own ballots to give to their voters to hand in at polling stations. Each state produced different ballots. Names could be changed, crossed off, and written in. Secret ballots were almost nonexistent. Voters known then as “floaters” would sell their votes to the highest bidder. Republicans were caught red-handed doing this in Indiana, a state Harrison won by merely 2,000 votes. While Cleveland did beat Harrison in the popular vote by almost 100,000 votes, he lost in the Electoral College when Harrison defeated him in Cleveland’s home state of New York by about 1 percent.

Dr. Speel suggested in a recent article in The Conversation, an online magazine for the academic and research community, that Cleveland’s loss in New York may have also been related to vote-buying schemes.

Remaining a Frontrunner

After reading a few of his articles, I reached out to Dr. Speel by email, asking what lessons Trump could learn from the Grover Cleveland model and apply to rerun in 2024.

Dr. Speel noted historical research is scant on how Cleveland managed his comeback. We do know that Cleveland returned to New York to practice law and avoided the spotlight for the next two years, before throwing his hat back into the ring for 1892.

“I don’t think Trump could do that, or that it would work in modern times,” Dr. Speel said. One tactic that could boost Trump’s chances is to shine the spotlight on election reform, as Cleveland did, rather than focus on his own personal wounds.

Writing for the Smithsonian magazine in November 1988, S. J. Ackerman noted that in defeat, Cleveland pursued a “nagging sense of duty about balloting,” calling upon “good citizens everywhere to rise above ‘lethargy and indifference,’ to ‘restore the purity of their suffrage.’ ”

Such elegant language is hardly Trump’s style, but by taking the high ground, Cleveland motivated a ballot-reform landslide that swamped the nation’s legislatures. In 1888, only Louisville, Kentucky, and Massachusetts were using a secret ballot system made popular in New South Wales, Australia. A year later, nine more states, including the infamous Indiana, adopted the Australian method. By the time Cleveland ran again in 1892, 38 states were voting by secret ballot. This time, Cleveland won by 3 percent, trouncing Harrison in the Electoral College 277 to 145.

Americans have every right to demand ballot reform after the highly contested 2020 election. However, if Trump is to be the political gilgul of Grover Cleveland, he must use his clout to advance the best interests of the American people, not just to further his own ambitions. He must also convince Republicans that he is their best and only chance to win in 2024.

“If most Republican voters and many Republican leaders continue to see Trump as the front-runner in four years, that may prevent strong opposition from forming against him in Republican primaries when he tries again,” Dr. Speel said. “But I expect Trump will gain some significant opposition within his party, especially with his unwillingness to accept his loss in this year’s election.”

The upcoming Georgia Senate runoffs on January 5, 2021, pose the biggest post-election test for Trump. If the Democrats win both seats and wrest control of the Senate from the Republicans, especially if large numbers of Republicans boycott the election to protest voter fraud, the recriminations against Trump might bubble to the surface. If Republicans win at least one of the two Georgia seats and retain control of the Senate, it will strengthen Trump’s hand in 2024.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 839)

Oops! We could not locate your form.