Divine Wisdom, Human Heart

| July 25, 2023Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin (1881–1973) was one of America’s greatest poskim

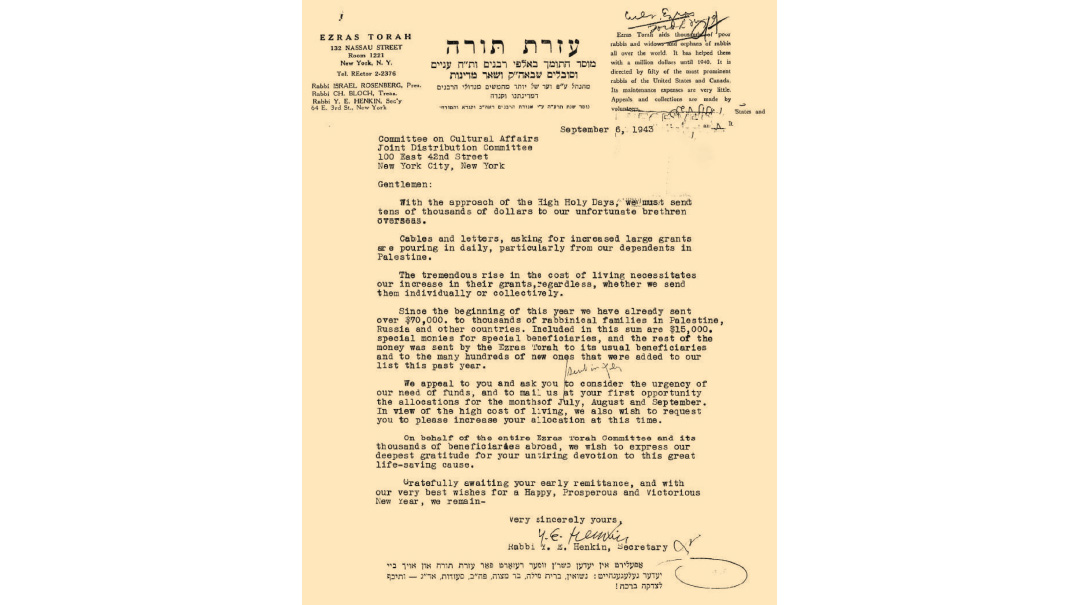

Even as America’s leading halachic decisor and the force behind Ezras Torah, Rav Henkin referred to himself only with the title of “secretary”

Title: Divine Wisdom, Human Heart

Location: New York City

Document: Letter from Rav Henkin on behalf of Ezras Torah

Time: 1943

His weekly salary as the director of Ezras Torah was $50 — a paltry sum, by any standard. At one of our meetings, a resolution was raised to increase Rabbi Henkin’s salary.

He immediately rose from his chair and declared: “Must I leave Ezras Torah?”

The less his personal benefit from Ezras Torah, the greater the aid for talmidei chachamim in distress. He was a baki b’Shas, as well as the four tracts of the Shulchan Aruch. Once, in my presence, he received an urgent phone call from Eretz Yisrael and he resolved the problem, which apparently defied easy solution to those who called him, relating to marriage laws, without reference to single sefer.

On several occasions I noticed Rabbi Henkin refer to a mysterious small notebook. He once revealed to me that in this notebook he kept a log of those minutes during the day that he did not utilize for Ezras Torah. He was not involved with his own personal business during those minutes, but when someone came to his office at Ezras Torah to discuss divrei Torah or if he received a telephone call, as he often would, from anywhere in the world requesting his opinion on a particular problem or sh’eilah, he immediately looked at the time and noted in his record how many minutes he had borrowed from Ezras Torah. He would then know how many minutes to “make up” on behalf of Ezras Torah-related work.

—From a hesped delivered by Rav Naftali Riff upon the passing of Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin

Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin (1881–1973) was one of America’s greatest poskim and one of the world’s greatest supporters of Torah in the 20th century. Born in Klimavichy in today’s Belarus, he arrived in Slutzk in 1897 shortly after the establishment of the yeshivah there, with Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer at its helm.

Upon testing the 16-year-old’s proficiency in masechtos Shabbos and Eiruvin, Rav Isser Zalman exclaimed, “This child knows these two masechtos better than I do!”

Young Yosef Eliyahu remained in Slutzk for six years, but his close association with Rav Isser Zalman — who gave him semichah — would be lifelong. He would also receive rabbinical ordination from Rav Yechiel Michel Epstein, the author of Aruch Hashulchan; Rav Yaakov Dovid Wilovsky, the Ridvaz, who was the rabbi of Slutzk; and Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, then rabbi of Halusk.

Following his marriage to Freida Rivka, daughter of prominent Chabad chassid Rav Yehuda Leib Kreindal, Rav Yosef Eliyahu was appointed to his first rabbinical position in Georgia, at the far reaches of the Czarist Russian Empire. The subsequent decade saw Rav Henkin serving in several Sephardi-style communities around Georgia, where he strengthened traditional Jewish life and initiated an active correspondence with some of the era’s prominent poskim, from which we can infer something about the many challenges he faced there.

Georgia is situated between the Black Sea and the Caucasus Mountains, at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. The Jews of Georgia trace their history back more than 2,600 years to the time of the destruction of the first Beis Hamikdash. The ancient Jewish community of Georgia had many unique traditions. It was believed that removing an item from a sick person’s home could provoke demons. Their nickname for Purim was “Rosh Hashanah,” and they believed drawing water in the middle of that night would ensure blessings for the new year. In their funerary rites, the deceased were adorned, and money and food were placed in their graves, and family even recited shehecheyanu. Rav Henkin took it upon himself to wean the community from these practices. He also invested considerable effort in building adherence to previously neglected areas of halachah, such as marriage and divorce law.

Rav Henkin did not do away with all the local customs. Over ensuing decades, he would elaborate on several practices pertaining to prayer that he admired, such as the community’s preservation of ancient Hebrew pronunciation. He deemed it more accurate, as it had been untouched by European influence. He specifically singled out Georgian Jews’ correct pronunciation of the letter ayin.

IN 1913 Rav Henkin returned to White Russia, where Rav Isser Zalman secured him a position as rosh yeshivah in Stoibtz. The rabbi of the town then, Rav Yoel Sorotzkin, had to take a short leave of absence, and was spelled for a time by a young unknown talmid chacham named Rav Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz. Rav Henkin was very taken by the young scholar, who would later be known to the world as the Chazon Ish. They developed a close relationship, studying together on a daily basis for several hours.

After a short stint in Shklov, Rav Henkin was appointed the rabbi of Smolyan, where he remained for the next eight years, leading his community through the tumultuous times of World War I, the Russian Revolution, the subsequent civil war, and the establishment of the Soviet Union.

With the Bolshevik repression of religion, his position became untenable, and he and his family emigrated to the United States in early 1923. Settling on the Lower East Side, he initially served as rabbi of one of the shuls in the area, and also affiliated himself with the two local yeshivos — RJJ and RIETS. He quickly became an active member of the Agudath Harabonim, trying to bring order to the chaotic kashrus scene as well as galvanizing American support for their Russian brethren. Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, whom Rav Henkin stayed in close contact with, appointed him the official representative of the Slutzk-Kletzk yeshivah in the United States, and he began fundraising for them as well.

The Agudath Harabonim appointed him in 1925 to head the Ezras Torah organization, which had been established during World War I by Rabbi Yisroel Rosenberg to assist rabbis and yeshivah students who were refugees or otherwise in need of financial aid. Rav Henkin’s name would soon become synonymous with Ezras Torah, and for the next half century until his passing he stood faithfully at its helm, assisting thousands of Torah scholars and institutions.

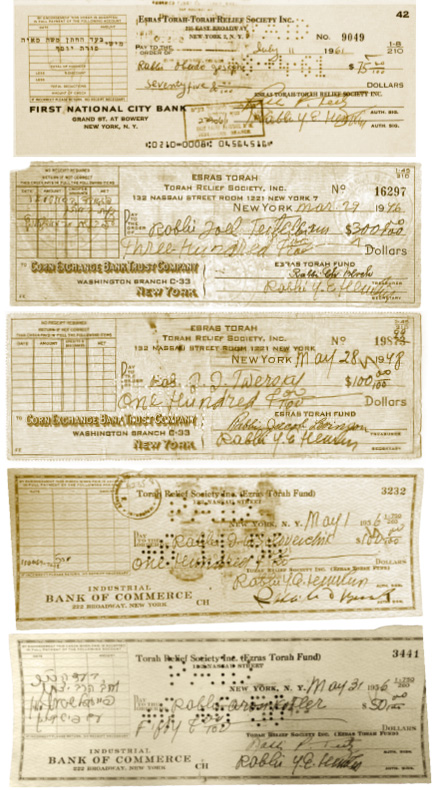

Ezras Torah under Rav Henkin’s long tenure distributed millions of dollars around the globe. Under his auspices, the organization kept the Torah world afloat during the dire interwar period, was a lifeline during the war years, and rebuilt the Torah world in the United States and Israel during the decades following the great devastation of the Holocaust. Throughout this time, Rav Henkin’s personal oversight of the raising and distribution of funds made him one of the greatest baalei chesed and builders of Torah in the 20th century.

Under the guidelines Rav Henkin laid down for the staff, Ezras Torah’s chesed would not be limited to writing checks. He assisted refugees with finding employment, immigration, and marriage. Even help arranging a beis din for divorce was provided as a chesed, should the need arise. Never taking a vacation, he showed up daily at the office into his late eighties, even coming in on fast days and Chol Hamoed. Shabbos was also devoted to Ezras Torah; he spoke at various shuls and traveled to communities across the country for weekend fundraisers.

During this same time, he emerged as a universally acknowledged posek, fielding thorny halachic questions from across the country and beyond. This was especially true regarding marriage and divorce law, due to the expertise he had garnered as a young rabbi back in Georgia.

He also built a close relationship with his illustrious neighbor on the Lower East Side, Rav Moshe Feinstein. Rav Henkin, 14 years his senior, was already the country’s leading posek when Rav Moshe arrived in 1936. Rav Henkin is mentioned dozens of times throughout Rav Moshe’s multivolume Igros Moshe, many more citations than any other contemporary posek.

Though they sometimes disagreed on fundamental halachic applications — such as their famous dispute regarding a get for a Reform divorce, which Rav Henkin held was required — the world’s greatest poskim lived side by side in harmony for decades. Another of Rav Henkin’s many landmark halachic decisions was his insistence that it is forbidden to eat on Rosh Hashanah prior to hearing the tekiyos.

Rabbi Emmanuel Gettinger, son-in-law of Rabbi Riff and his successor as president of Ezras Torah, recalled that while he was in Tzfas during a visit to Eretz Yisrael, a wizened old man approached him.

“Are you from America?” the man asked.

“Yes,” replied Rav Gettinger.

“Oh, I have a father there. His name is Rabbi Yosef Eliyahu Henkin.”

Fifty years ago on 13 Av, Rav Henkin was niftar. In his will, Rav Henkin requested that he be buried in a simple grave (at Beth David Cemetery in Elmont, New York), with the following inscription:

Rav Yosef Eliyahu son of Rav Eliezer Henkin, author of Perushei Ivra and Lev Ivra, formerly rabbi of various communities in Russia, and in this country in the Synagogue of Anshei Shechuchin and Greive, and director of the holy organization Ezras Torah.

He stipulated that “they shouldn’t embellish with additional titles.” It is quite rare in Jewish history to have a personality who embodies a life of total support for Torah and its institutions and scholars, while at the same time rising to prominence as the universally renowned posek of his generation. Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv once referred to him as “the mara d’asra of America.” And in many ways, he indeed was.

Photos: Genazim Auctions, Legacy Auctions and Rabbbi Yosef Shaul Hoizman

Ezras Torah provided badly needed support for thousands of rabbanim around the world, including great leaders like the Satmar Rav, Brisker Rav, Rav Ovadiah Yosef, Rav Aharon Kotler and the previous Skeverer Rebbe

Around the Year with Ezras Torah

The Ezras Torah Luach (calendar) expressed the synthesis of Rav Henkin’s twin roles as head of Ezras Torah and premier posek. Ostensibly a promotion for Ezras Torah, Rav Henkin utilized the luach to publish the basic halachos for Jewish communities across the country. As the American equivalent of Rav Yechiel Mechel Tukachinsky’s Luach Eretz Yisrael, the calendar was filled with halachos of davening, zmanim, shul, Shabbos, holidays, life cycle events, and customs. For many far-flung communities across the country, this was a mainstay of Jewish communal life for decades.

An Encounter with Evil

Around 1913, toward the end of his time as rabbi of the town of Kulashi in Georgia, Rav Henkin had a frightening encounter while traveling on a “troika” (shared wagon), with someone the writer understood to be Iosef Vissarionovich Jugashvili, a native Georgian later known to the world as Josef Stalin, tyrannical ruler of the USSR. Rav Henkin conveyed the details of this strange incident to the journalist Aharon Ben Tzion Shurin, who shared the story in a Forvertz profile:

[Stalin] engaged R. Henkin in conversation. First he praised the Jews, even expressing sympathy for the persecutions they suffered under the Czar and elsewhere. He spoke this way until he began to drink. When they stopped at an inn along the way, he descended from the wagon and drank several shots of vodka, whereupon his mood changed. Then he opened his mouth and spoke in a different vein: He cursed the Jews and heaped scorn and derision upon them. He blamed them for everything: being bourgeoisie, exploiting people, and responsible for all the world’s ills. During one of these rants, Stalin invited R. Henkin to join him in a shot of vodka. Looking at the murderous face, R. Henkin feared for his life. Even today, when R. Henkin remembers that strange encounter, he feels compelled to recite birches hagomel again.

It’s likely that there was some sort of misunderstanding in recording this story. The encounter most probably wasn’t with Stalin, rather with another brutish personality whose identity has been lost to time. Aside from the fact that Stalin wasn’t much of a drinker, in 1913 he was living in St. Petersburg and spent some time in Vienna. Upon returning to Russia in February, he was arrested by the Czarist police for revolutionary activity and exiled to Siberia, so it’s doubtful that Rav Henkin met him in Georgia during this time.

The research and writings of Rav Eitam Henkin Hy”d were utilized in the preparation of this article.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 971)

Oops! We could not locate your form.