Distilling Memories: The Grandfather I Thought I Knew

How could he take responsibility for them when he had failed with Beirish?

My father remembers it vividly. It was 1955. Uncle Beirish, Bobba’s brother, was visiting from Galveston, an island city on the Gulf Coast of Texas. Uncle Beirish was in the furniture business and had come to New York for a trade show. My father was 16 at the time. His family lived in Crown Heights, on the second floor of a two-family home on Montgomery Street. His grandparents, Zeida and Bobba Rosenblatt — my great-grandparents — lived downstairs.

Uncle Beirish rang the doorbell. Bobba opened the door and welcomed him. Zeida, who had suffered a massive stroke years earlier and was paralyzed on his left side, was in the living room, resting on the large chair he favored. When Zeida heard Beirish’s voice, he pulled himself up and, with his cane, dragged himself out of the living room to the kitchen. Zeida would neither look at nor speak to Beirish.

Anger had stewed between them for decades. Back in 1910, Zeida had been invited by landsleit to be a shochet and rav in their small heimish kehillah in Galveston. Two years later, Zeida brought Beirish over to join the family and help in his meat business.

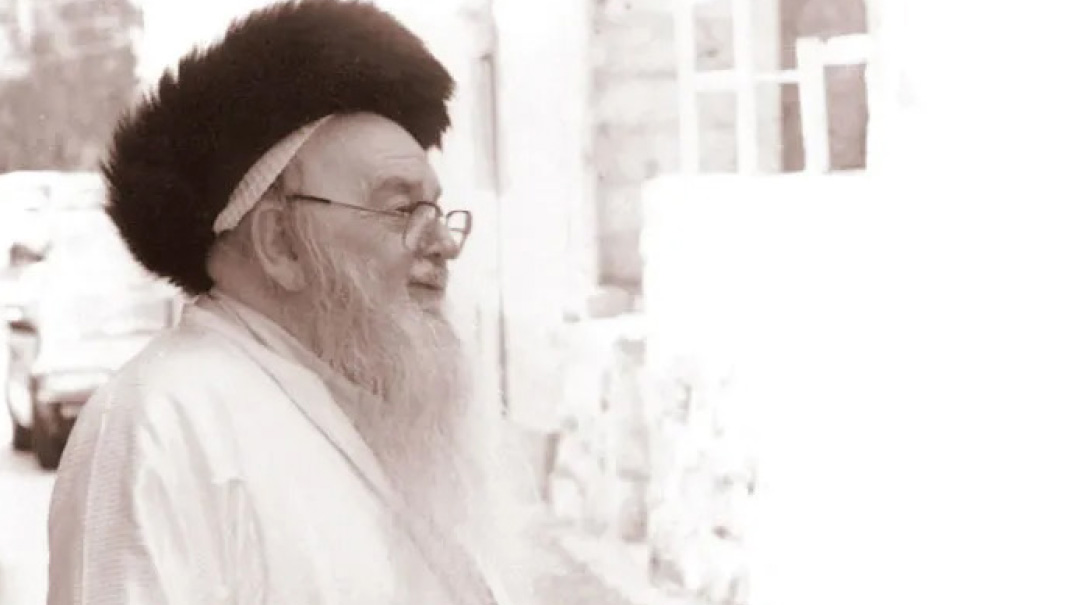

The family was from chassidish stock. Bobba’s father, Velvel Shochet, was a chassidishe Yid. We have one photo of him wearing a shtreimel on Erev Shabbos. Zeida had promised to take achrayus for Beirish. Unfortunately, while he was able to keep his own seven children frum in Galveston, he was unable to keep Beirish in the fold.

Had Beirish remained frum, Zeida would have brought over the rest of his siblings from Burshtyn, Galicia. They would have joined the small, growing kehillah in Galveston.

But when Beirish became frei, Zeida refused to bring over anyone else. How could he take responsibility for them when he had failed with Beirish? Better they should remain in Europe. The years 1910 to 1914 were when Zeida could have brought over the family. The world was at peace, his siblings were young, and America welcomed immigrants. And his successful business put him in a position to help them.

But then the world went mad. In the summer of 1914, World War I broke out. Europe was engulfed in flames. Travel to the US was impossible. And when the war ended in 1918, the opportunity had passed. Beirish’s siblings were older, married, and traumatized. Moving was not easy. Also, the US had changed its immigration policy and it was difficult to get a visa.

In 1925, after 15 years in Galveston, Zeida realized there was no frum future for his family on the Island. He moved to New York, where he opened a butcher store. Beirish, who had married a local Jewish girl, remained in Texas. Over time he became a leading member of the Galveston Jewish community, part of the synagogue led by Zeida for so many years, which left Orthodoxy and joined the Conservative movement. Bobba and most of the children maintained a relationship with Beirish, the young uncle they knew and loved growing up in Galveston.

The 1930s were difficult years for all. Then World War II began and the Nazi beast destroyed Jewish Europe. Tragically, most of Zeida’s siblings and their children were slaughtered. Only a few survived. A brother settled in France. A nephew moved to Israel, another to Brazil. Zeida was devastated. In 1948 he suffered a massive stroke that left him unable to work. My grandfather, his oldest son, took over the butcher store and, in time, moved into the upstairs apartment in Zeida and Bobba’s Crown Heights home.

That was the backdrop of Beirish’s 1955 visit. It was a full 30 years after the family left Galveston, seemingly the first time they were seeing Beirish. And Zeida would not look at him.

The ways of the mind are not always explicable. It’s hard to imagine that we can be held accountable for decisions others make as a result of our choices; it is enough to be responsible for the choices we make. To me, the story my father recounts says less about Beirish than about Zeida.

It speaks about the powerful, patriarchal personality that kept a family frum and overcame the draw of the melting pot that was America at the time. Most remarkable, in hindsight, was that Zeida left the shul and business he built over 15 years to move his family to New York and start again at the age of 42. Surely, he could have hired a new Galicianer melamed and paid him well to teach his children. Surely, he could have reasoned that his children would follow his moral guide because he was the rabbi. But he had no such illusions. He and Bobba packed their possessions, left it all behind, and moved to New York.

In 1995, I visited Beirish’s three elderly children, still living in Galveston. Jack, Joy, and Myrtle were warm and welcoming. A picture of Velvel Shochet sat on a table, just like the one that hung in my parents’ home. A large portrait of Beirish hung on the wall. He looked dignified. He was not frum but proudly Jewish and the patriarch of their family. We saw the synagogue, built, they said, on the spot where the family had once lived. I tried to stay in touch, but over time the interactions faded away. Sadly, many of their grandchildren married out.

I have thought a lot about Zeida. The pictures we have show him smiling. But he must have been fierce and unforgiving when it came to issues of Yiddishkeit. He made the decision to not bring anyone else over from Europe. But was he still convinced even in the 1930s? Did Zeida do nothing for his siblings, even as the Nazi beast enveloped his family in Galicia? The question lingered in my brain.

In July 2018, I received a call from Rabbi Naftali Zvi Horowitz of Boro Park. He had found documents that related to his grandfather and he thought they might interest me. It was an application for a visa from Kobe, Japan, to the US, filed in 1941. His grandfather had traveled east from Europe and was stranded in Japan. His great-grandfather was already in the US and trying to prove that he was financially able to sponsor his son, so he would not become a public charge. Zeida had written a letter attesting that the grandfather, the Riglitzer Rav, was the machshir of his butcher store and made $500 a year.

According to Rabbi Horowitz, this was an extension of reality, and seemingly an attempt to help a Jew escape Japan and be allowed into the United States. The letter Zeida sent did not succeed, as in December 1941 Japan attacked the US at Pearl Harbor and travel across the Pacific was no longer possible. Instead, Rabbi Horowitz’s grandfather was sent to Shanghai where he remained for the war years, arriving in the US in 1946.

To Rabbi Horowitz, this letter was a way to connect to a descendant of someone who tried to help his grandfather. To me it did much more. It calmed my soul. It was important for me to know that Zeida did this for someone he did not know. If he did this for that man, surely I can believe he did all he could for his siblings.

Zeida was a chassidishe Yid who brought his family to America and succeeded in a test that most failed. He made the best decisions he could, using the information he had. He did all he could to try and save his family. And as the generations pass and new generations sprout, his family endures, living the values and the mission that he dedicated his life to uphold.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 796)

Oops! We could not locate your form.