Diplomatic Immunity

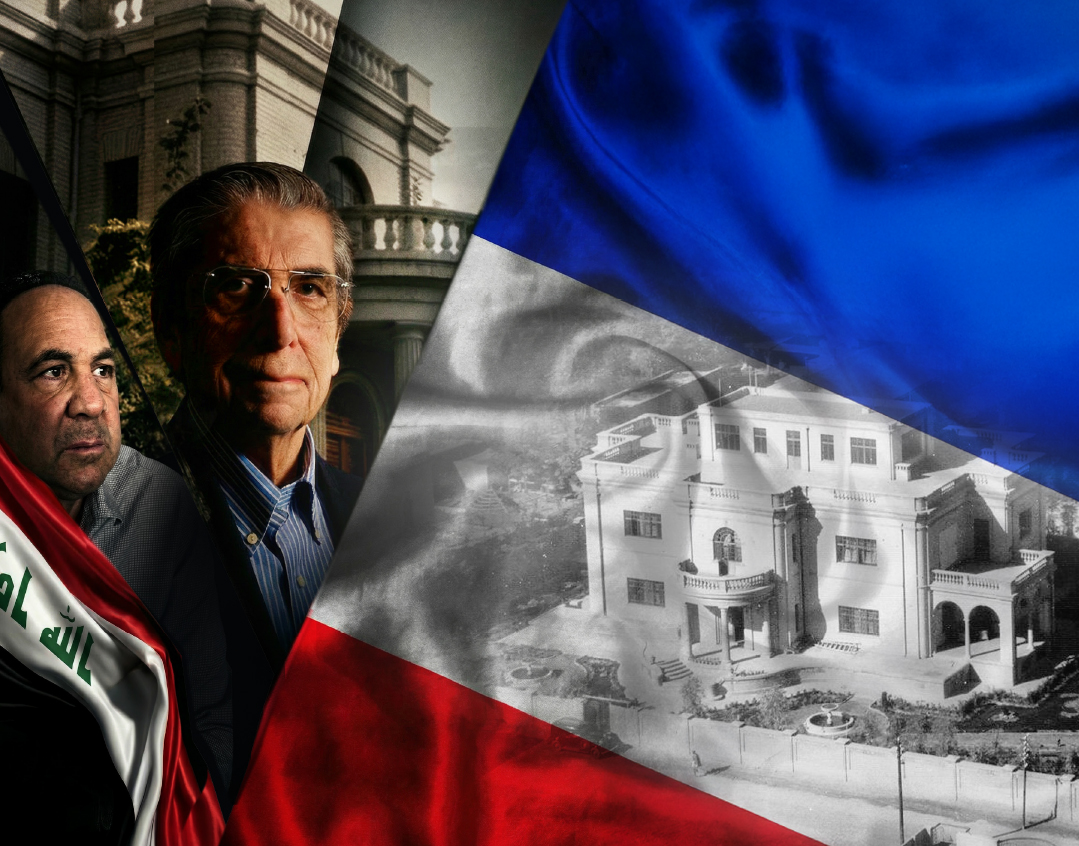

He's an Arab, a Christian, and an Israeli Ambassador. George Deek makes the unlikely case for his country.

Photos Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Shortly after taking up his new position as Israel’s ambassador to Azerbaijan in 2018, young, personable, and articulate George Deek sat down for an introductory talk with a local government minister that left the Azeri official confused.

After the initial pleasantries, the conversation turned to the deep-rooted Azeri tradition of tolerance that has allowed a Jewish community to flourish in the country for centuries.

“Our two communities go back a long way,” ventured the minister, referring to Muslims and Jews, who have long coexisted peacefully in the South Caucasus.

“That’s very special,” replied the ambassador, “but did you know that I’m actually an Arab?”

Nonplussed, the Azeri minister attempted to reorient himself and began again. “Ah, yes, so then you and I are Muslims…” he clarified.

But the Israeli diplomat still hadn’t finished. “No, I’m actually not a Muslim,” he told the bewildered dignitary. “I’m a Christian.”

“It was just too much for him,” George Deek shares with me in a recent interview. “An Arab-Christian turning up as the Israeli ambassador to Azerbaijan — he didn’t know how to process it.”

“Who are you?” is really the story of Deek’s life. If Israeli diplomacy is all about telling Israel’s complex story to a world that thinks in black and white, the ambassador’s own hyphenated existence is the technicolor version.

A Yafo native whose family has been in the country for centuries, he’s named after a grandfather who fled during the War of Independence, then returned to Israel once the reality of Arab propaganda became clear.

Even though he’s the son of an Arab nationalist, the 37-year-old is convinced that Israel is one of the best things to have happened to the Middle East. A practicing Christian, he developed an unusual connection with the late Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks.

George Deek’s path to evangelizing for the Jewish state was anything but straightforward. His radical ideas about the need to leave Arab grievances behind were seeded by a Holocaust survivor who taught him music — and crucially, how to look ahead despite a bitter past.

“Like the smallest figure in a set of Russian nesting dolls,” he says with a characteristically neat turn-of-phrase, “we’re a minority within a minority in a country that is itself a minority.”

But Deek’s story is one often-overlooked as part of a complex, larger narrative about Israel. It’s not just external actors like Iran — across the border from his new host country, which the Mossad reportedly uses as a forward base — that threaten Israel. As the Arab-Israeli riots of this past summer show, Palestinian violence is a cauldron that can quickly boil over.

Yet that’s what makes Deek’s story so compelling. He’s part of a young Arab-Israeli generation that, on the other hand, is also fumbling its way to a new accommodation with the Jewish majority, more interested in improving the quality of their lives than fighting for a Palestinian state that they’d prefer not to live in in any case — and, as Israeli Arabs, isn’t even their personal fight.

“As Arab national identity crumbles, there’s a shift underway,” he says. “Some, like ISIS, react with fear. I see different responses happening in parallel.”

But, as the summer riots indicate, it’s not so simple. Is George Deek a test case that can actually work?

Beyond his bio — he grew up in the mixed Jewish-Christian-Muslim city of Yafo, was the only Arab in a Jewish high school, is a graduate of Radzyner Law School in Herzliya and also studied at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. on a Fulbright Fellowship — George Deek’s optimism after serving as deputy ambassador to Norway during the 2014 Gaza war is worth hearing. Posted to a progressive anti-Israel hotspot, his own success story growing up in a country his hosts will casually refer to as an “apartheid state” gave Israel the hearing it’s often denied among its detractors.

“I’m going to shock you,” he told audiences in Oslo, the city that gave its name to the failed peace process, in a speech hailed as one of the best ever delivered by an Israeli diplomat. “The existence of a Jewish state is at least as important to me — an Arab Christian — as it is to any Jewish Israeli. The simple truth is that a Middle East that has no room for a Jewish state is a Middle East that has no room for anyone who is different.”

This polished, unapologetic defender of Israel — in both personal encounters and active social media — has been making Israel’s case to hostile audiences for close to a decade in a language that resonates with them, unfazed by jeering crowds (in 2016, he calmly faced a heckling audience at the University of California by writing an appeal for dialogue on the whiteboard behind him).

No Victims Here

As patriotic as he is as a representative of Israel’s foreign ministry, Deek is still part of a distrusted minority — an outsider among Israeli Jews, yet viewed with suspicion by some Israeli Arabs who want to know whose side he’s really on. But Deek is no follower of the playbook that says every Arab who’s succeeded in the political realm has to become a defender of the Palestinian cause and a thorn in the side of the government.

It was his grandfather, George Deek senior, who first parted ways with Arab propaganda. An electrician living in 1940s Palestine, he worked for the then-Palestine Electric Corporation, now familiar to Israelis as the national utility, Chevrat Hachashmal.

The Deek family had a tradition in the Holy Land that went back 400 years, and while Jewish-Arab tensions mounted steadily from the 1920s, George himself got on well with his Jewish neighbors. Many of the company’s other employees hailed from Eastern Europe, so he even learned to speak a smattering of Yiddish.

But as the British prepared to end their Palestine mandate in 1948, that era of coexistence came to an end.

“The family heard about the Deir Yassin massacre,” says his grandson, referring to a botched Irgun-led attack on a Palestinian village located in what’s now the commercial area between Givat Shaul and Har Nof. “The Arab leadership warned that Arabs would be slaughtered by the Jews if they didn’t leave and promised to destroy the newborn Israel. So, my grandfather hurriedly married his fiancé, and they fled north to Lebanon.”

The fleeing Arabs were told that if they left temporarily, they could return after the Arab victory and take back their homes. The flight of some quarter-million Arabs at Israel’s birth was part of the narrative of the Nakba, the “disaster” of Israel’s birth, on which generations of Palestinians have been raised, feeding the seven-decades-long storyline of refugee status and persecution.

But George Deed senior realized he’d been deceived. The Arabs didn’t win the war, but neither were they slaughtered. And he didn’t have any desire to spend his future as a refugee. “My grandfather saw that there was no future in Lebanon,” says Deek. “Members of his family moved everywhere — to Jordan, Canada, Australia — but he wanted to return to Yafo.”

And so, he did something few others did — he contacted his old colleagues in the power company, those his community saw as enemies. George and his wife smuggled themselves back over the border into the new Jewish state, and when George was arrested and thrown in jail, his former Jewish coworkers came to his aid and enabled his return to Yafo and helped him get back his old job.Deek says his grandparents’ move was a powerful impetus for his own life. They could have been angry, resentful, and full of revenge. But instead, they rebuilt their life, educated their children, and provided them with opportunities. And that, he says, is why today he’s an Israeli diplomat and not a Palestinian refugee or a frustrated Israeli Arab, mired in the destructive mindset of victimhood.

“You don’t have to be anti-Israel to see that this was a humanitarian tragedy,” Deek told his Oslo audience in 2014. “But why is this the only conflict that’s remembered? The Kurds lost their homes in Iraq; the Yazidis and Christians were recently expelled and will never reclaim their homes. On the other side, in 1948, 800,000 Jews were intimidated into leaving Arab countries.

“The way that the Nakba has been transformed from a human disaster into a political weapon,” he continued, “can be seen in the date chosen to mark it. It’s not the date when Arabs fled, but May 15th, after Israel’s independence. In other words, the day doesn’t mourn the fact that my cousins are Jordanian — it mourns the fact that I’m Israeli.”

Who Will Be Left?

While the Deeks never forgot that lesson of openness, the home that George was raised in was, in fact, permeated by Arab nationalism — hardly a natural stepping stone to the Israeli foreign service.

His father, who worked as a tax advisor, was one of the leaders of the Christian community, and in 2015, a square in Yafo was even inaugurated in his memory. But he was also an Arab nationalist political activist.

“My father was the head of the Yafo branch of the nationalist Balad party,” says Deek. “Arab Christians were actually the founders of the Arab nationalist movement that at one time held sway across large areas of the Middle East, including in Iraq and Syria’s Ba’ath parties. Christians were always considered by Islam, like Jews, to be dhimmis, or second class. So naturally, when nationalism arrived in the Middle East from Europe in the 18th century, proclaiming that religion didn’t matter and that Arab identity was core, Arab Christians embraced the idea.”

But as much as Arab nationalism was the culture of his home, a formative influence on George Deek’s outlook wasn’t a member of Yafo’s Arab community, but a Holocaust survivor who’d made the mixed Jewish-Arab town his home.

“When I was seven years old,” Deek relates, “I went to study music under a man called Avraham Nov. Avraham was his family’s only survivor, and the Nazis had kept him alive because of his musical gifts. He could have spent his life in bitterness, yet instead, he decided to look forward and deal with the tension he saw in our town by teaching hundreds of Arab children like me.”

That living example helped Deek see that harking back to the past — as Palestinian rejectionism does — was no way to live. “Palestinians are slaves to the past in chains of resentment,” he says.

As part of the anti-Semitic narrative prevalent across the Arab world, Holocaust denial is widespread across the Middle East. But the interactions with his music teacher actually made the Holocaust central to young George Deek’s views of identity in a positive way.

“You know the famous poem by Pastor Niemöller, ‘First they came for the Jews, and no one spoke up…’ That’s how I came to think of the Middle East. Jews are a minority in the Middle East, and no one in history has ever paid a heavier price for being a minority than the Jewish people. If we don’t deal with radicalism when it comes to Jews, then no one will be left to speak up when they come for the Yazidis and the Christian minorities.”

That understanding, says Deek, is what’s behind the openness of the young generation that led to the Abraham Accords peace breakthrough last year.

“The Emiratis realized how true it was for them as well. Their neighbors, Iran, spread a culture of hate, as do groups like ISIS. There’s now a convergence of countries from Egypt to the UAE who oppose what politically-extreme Islam is doing to the Middle East.”

High Flier

Visible via Zoom on the dark-blue walls of George Deek’s office in the embassy are portraits of the new political guard, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and President Yitzchak Herzog.

“Yes, I was used to the old ones,” Deek says of Netanyahu and Rivlin, whose likenesses adorned embassy walls for years.

Bibi may be out of office, but when George Deek speaks about his own community’s contribution to the country, he sounds almost like Bibi giving a boosterish AIPAC speech about Israel’s contribution to humanity.

The success of Arabs in Israel, those who’ve transcended small-mindedness and motifs of victimhood, is a passionate subject for Deek, who notes with no little irony that it’s thanks to the establishment of the State of Israel that so many in the Arab sector have become successes in the fields of medicine and high-tech.

“Did you know that 40% of Israel’s doctors and 60% of pharmacists are Arabs?” Deek says, a fact that anyone who’s been to an Israeli pharmacy is probably aware of. “George Kara, a Supreme Court judge, is from Yafo; some of the leading scientists are Arabs. Just like the Jewish people has done as a minority in the Diaspora, preserving its faith while contributing to the general good, we also contribute to the general welfare.”

Yet many Israeli Arabs don’t move forward because of their own ideological obstinacy, a fact that’s made Deek a target of hostility among the very people he wants to see advanced.

But even for those who’ve broken through the ideological barriers, few, Deek admits, have gone so far as to actually become symbols of the Jewish state.

“I actually became a diplomat because I was bored as a lawyer,” he admits. “In 2009, I saw an advert for a foreign service cadet course. I actually didn’t know much about what the service was, but after I was accepted, I went to see my father.”

“ ‘Dad, in your position as Balad head this might cause you some problems,’ I told him. ‘You just tell me if I should do it or not.’ Then he smiled and said, ‘George, if I were you, I wouldn’t do it. But my job was to teach you how to think, not what to think.’

“When I graduated the Foreign Ministry training, he came to the ceremony and watched with tears in his eyes. Sadly, he passed away just a few months later.”

While George Deek’s father wasn’t around to get the Arab-Christian version of nachas from his high-flying son, the diplomat has definitely made waves in his various postings.

After a 2009-2012 stint as deputy-ambassador in Nigeria — effectively an apprenticeship to round out the training — Deek was thrown in at the deep end as envoy to Norway.

In one of the most progressive places on earth, he came face-to-face with an anti-Israel bias that often crossed the line to overt Jew-hatred. “In Oslo, I once went out for a drink and was talking to a local, when her friend came over and said in English, ‘He’s from Israel, he’s a dirty Jew.’ ”

Shocked by the blatant anti-Semitism, Deek’s minority philosophy kicked in. “I had a choice: I could have said I wasn’t Jewish, but I thought to myself that if this is how they treat a Jew just because he’s a Jew, then tomorrow it could be me. So, I didn’t say anything, which I guess makes me the victim of an anti-Semitic attack.”

The roots of progressive disenchantment with Israel are deep, and the path by which the pro-Israel left of the 50s became the BDS of today is widely-debated. But having seen the anti-Israel movement close up, Deek has his own explanation, one that strikes at the heart of Western bigotry against Israel.

“My take is that Norwegians don’t see Israel as a normal country, with a natural right to self-determination. No one claims that because of the Holocaust, Germany has no right to exist. But people believe that Israel is a Western guilt project, compensation to the Jewish people for the Holocaust. And as far as they see it, that comes with strings attached: You can keep sovereignty only as long as you behave like we Norwegians would.

“The obsession with Israel,” Deek reflects, “is because they feel a certain sense of ownership.”

Given that dark analysis of liberal bias, should Israel’s defenders give up on the left as a lost cause?

“Our success in Norway shows that no, we can have an impact,” says Deek emphatically. “I made Israel’s case in 58 interviews in 51 days in a hostile media environment during the 2014 Gaza war. And we succeeded. In the three years that I was there, we turned one of the most critical anti-Israel countries in Europe into a friend, especially on the political level.”

Neighbors and Friends

Looming over our conversation is the country that literally looms over the horizon for Deek’s Azerbaijani hosts.

Iran is at once Israel’s greatest strategic threat and the catalysts for closer relations with Arab countries based on the principle of mutual enemies.

A slow drip of reports about Mossad activities points to Azerbaijan as a forward base for covert action against the Islamic Republic’s atomic and missile programs.

Word has it, for example, that the nuclear archives snatched by Israeli spies in 2019 were exfiltrated via Azerbaijan. Israel also supplies advanced weaponry such as drones to the Azeris, which helped them to victory in their recent conflict with Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh, a separatist region. In addition to the country’s historic philo-Semitism, it’s one of the reasons why Israeli flags can be seen across Azerbaijan.

George Deek is naturally tight-lipped about the covert aspects of the relationship. Instead, he points to Azerbaijan as another example of Islamic extremism’s failure.

“Azerbaijan is Iran’s greatest failure. Here you have a small, Muslim-Shiite neighboring country, which should be the perfect place to export the Islamic revolution,” he explains. “Instead, Azerbaijan is a secular country where Jews live in peace side by side with their Muslim neighbors, women are emancipated and alcohol is allowed.

“And now, as Iran tried to bully Azerbaijan to cut its ties with Israel, the Azerbaijanis responded with a resolute position: No. Because they know that Iran wants to turn Azerbaijan into a failed satellite state, as it did with so many of our neighbors — Lebanon, Syria, and many more.”

Now well into his third posting abroad, the Israeli diplomat retains a sense of wonder for his job that’s infectious. “I’ll have some good stories to tell my kids,” says Deek, who got married two years ago. “I’ll tell them how I traveled with former Prime Minister Netanyahu to meetings with world leaders, including to the general debate speech at the UN in New York, and the little stories that happened behind the scenes. How one day we had breakfast with the President of Argentina in Buenos Aires, lunch in Colombia with its president, and then dinner in Mexico with the prime minister there.

“Definitely one of the more colorful memories is from 2011, when I was posted in Nigeria, and the king of Enugwu-Ukwu, one of Nigeria’s largest tribes of the Igbo ethnicity, approached me,” he continues. “We’d become friends, and he told me that the Niger River, the tribe’s water source without which life cannot be sustained, had become extremely polluted. This is the water they drink, the water they bathe in, where they wash their clothes. He asked if there was anything I could do to help.

“So, I reached out to a few Israeli water and irrigation companies and encouraged them to help us in a humanitarian project, in return for good PR. Within a few weeks, we had boreholes to provide them enough water to drink, and irrigation systems with seeds to grow tomatoes and peppers that they eat and sell on the local market. As a gesture of gratitude, the Igwe, the king, invited me to visit the tribe on my birthday, and there came many other tribal chiefs, and they decided to make me a chief among them.

“They named me Nwanne di Namba, which means ‘our brother abroad.’ It was definitely one of the most gratifying days I’ve ever had.”

But if George Deek has come a long way from his childhood home in Yafo, he’s still very conscious that his bold choice is controversial.

“Not everyone likes what I’m doing, but that’s okay,” he says. “I’m comfortable with the path that I’ve chosen. I don’t have easy answers. In fact, I often have more questions than answers.”

That last reference is George Deek’s admission that despite the strides that he’s personally made and as far as he’s come, not all is smooth sailing in a minority-majority relationship fraught with nationalist tensions on both sides. For example, Jews desecrated Arab gravestones in Yafo — including that of Deek’s father — as part of a “price tag” incident in revenge for Arab violence. “I accept that as part of who I am,” says Deek of the complexity, “and the quest for answers, or better questions, as part of why I am here.”

But shadows aside, George Deek’s outlook is sunny as he considers where the last years have taken him — an Arab boy whose grandfather decided to come back to Israel instead of stewing in hate and victimhood.

Success, in Deek’s case, is about the messenger as much as the message, but he’s adamant that Israel has a story to tell.

“I think the Israeli story is a remarkable one, also to progressives, if we just tell it right,” he says, hammering the same point home in a language even the anti-Israel left can embrace. “If we are unable to accept a Jewish state, then how will we be able to accept other minorities in our midst? Jews were not the only ones to suffer under the inquisitions, the pogroms, or the Nazis,” he avers. “Today, when we see the ethnic strife and the religious bloodshed in our region, the persecution of Christians, Yazidis, and other minorities, it becomes clear — once again — that the hate that begins with Jews never ends with Jews.”

“He Needs A Wife”

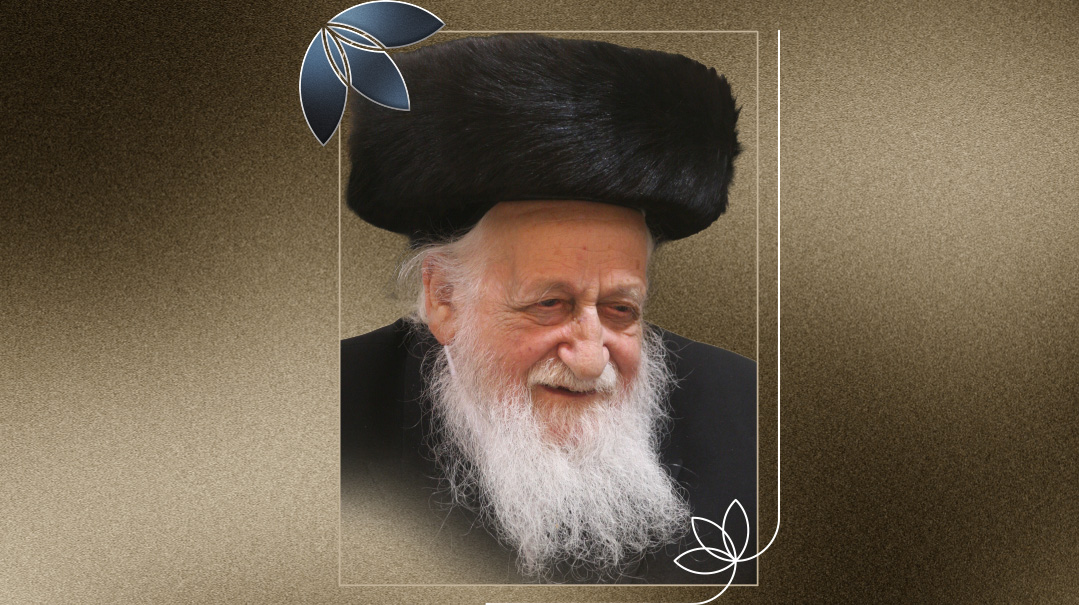

It’s almost exactly a year after the petirah of Britain’s chief rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks that George Deek sends me what must be one of the most unusual video clips Rabbi Sacks ever recorded.

It was a personal — and quite emotional — mazal tov video on Deek’s forthcoming wedding. And it was all the result of a reference to the chief rabbi’s books that Deek had made in a speech in Oslo.

“Israel is constantly attacked in Norwegian media, and when I was exploring different material about Israel, someone recommended that I listen to what this British rabbi had to say,” Deek relates. “I searched online and found an AIPAC speech that he’d given a year or two before. It began familiarly, and I thought that it was going to the standard take on the Holocaust, etcetera. But then it took a different direction, and I found it mind-blowing. He talked about the importance of preserving difference, and the way that he connected it to Israel was stunning. Rabbi Sacks became one of my primary sources of inspiration in the way I see morality and the relationship between Israel and other countries.”

The video of Deek’s resulting Oslo speech was posted online where it can be seen today, and word of the young ambassador’s talk made its way to Rabbi Sacks’s office.

“About three years ago, Rabbi Sacks was in Israel and his staff reached out to me with a note from the rabbi in appreciation for my words. We stayed in touch and eventually met in Jerusalem. We had a marvelous conversation about Jewish-Arab relations and the role of minorities.”

The admiration was mutual. “I was so impressed when I met you a while back and understood what a remarkable diplomat and human being you are — a force for generosity of spirit and tolerance, a force for peace in such a dark and dangerous world,” Rabbi Sacks announced on the clip he sent the ambassador. “And I thought to myself, this young man is totally brilliant, he has a wonderful personality, there’s only one thing he doesn’t have — a wife! So we thank the Almighty for providing you with that… May G-d bless you both, and may you continue to be a blessing for one another and to all whose lives you touch…”

“I was so touched by his video message, and extremely saddened by his passing last year,” says Deek. “He gave me a deeper understanding of things in his humorous way… Besides which, I learned from him to have the courage to wear yellow ties.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 886)

Oops! We could not locate your form.