Diplomatic Channels

When Panama was looking for an ambassador to Israel, Ezra Cohen was the go-to choice

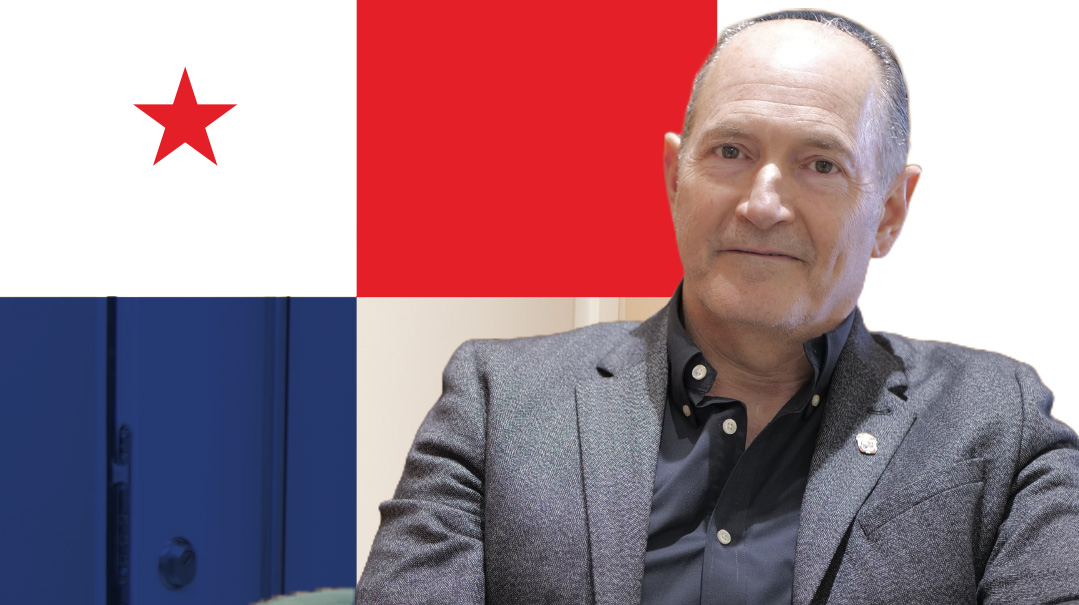

Photos: Ezra Trabelsi

When Panama was looking for an ambassador to strengthen ties with Israel, all paths led to a frum Jew named Ezra Cohen, a successful businessman and former head of Panama’s Jewish community who’s brought thousands of Jewish tourists to this Central American hotspot. Decades after his own father returned to Jerusalem from Jordanian captivity, Ezra Cohen arrived in the capital to a statesman’s welcome

IN Arizona in late December 2024, Donald Trump delivered his first speech after being reelected president. True to form, over the course of 75 minutes, he unleashed a stream of extravagant promises about America’s imminent return to greatness. Buried among his grand declarations — such as his official renaming of the Gulf of Mexico to the “Gulf of America” — was one grievance that had probably never figured high on the average American’s list of concerns.

“China has been running the Panama Canal,” Trump thundered. “We didn’t give it to China — we gave it to Panama. And we are taking it back!”

The crowd erupted.

Despite the applause, Panama remains, for many, lodged in a peculiar sort of limbo — a country whose name is familiar but whose other details are vague. There are places we know by name, yet we have little idea of where they are, or what happens there. For anyone from South America (this writer included), it is a common experience: Foreigners may know the name of your country but almost nothing else about it — its customs, its landscapes, its geography. Often, they can’t even find it on a map.

When religious Jew Ezra Cohen was offered the ambassadorship of his country to Israel, the mission was clear: To make Panama “locatable” on the map, at least in the Israeli consciousness. Cohen, who had spent much of his life in the business world, prefers to frame the challenge in his own terms.

“I used to sell electronics,” he says. “Now I sell Panama.”

For years, Cohen served as the executive director of the Jewish community of Panama, a role that brought him into contact with many of Israel’s social and political elite, long before he ever imagined himself in a diplomatic post. Business leaders, roshei yeshivos, politicians — they all knew the drill. Upon arrival in Panama, their first stop was Ezra’s office. That network of connections would ultimately propel him to his current post in Tel Aviv, where he seems to have found a role for which he was made.

But there’s a deeper story. In some ways, it closes a personal circle that spans eight decades. It is a story that begins during Israel’s War of Independence, when Cohen’s father was captured by Jordanian forces. He was later freed in a prisoner exchange, an ordeal that led him to leave the nascent Jewish state and begin a new life — far from conflict, in Panama. Now, some 80 years later, his son returns, not in retreat, but as Panama’s official representative to Israel — at a time many consider the most challenging since the country’s founding.

Oops! We could not locate your form.