Digital Witness

| October 12, 2021A savvy teen finds social media stardom for his Holocaust survivor savta

Photos: Mendel Photos

Mrs. Lily Ebert, a 97-year-old great-grandmother, has been sharing her Holocaust experiences for decades in all sorts of public forums. But it was still quite a surprise when, aided by her 17-year-old great grandson Dov Forman — she became one of the most unlikely stars on the TikTok social media platform.

TikTok, a short-form, video-sharing app that allows users to create and share 15-second videos on any topic, is a favorite of young people who post genres like comedy, dance, and pranks. So how did Lily and Dov’s “ask me anything” Holocaust history clips garner 1.3 million followers and 17 million likes by revealing the experience of one elderly Holocaust survivor?

The mostly young followers of Mrs. Lily Ebert have watched the petite near-centenarian (she’ll be 98 in December) light her Shabbos candles, listen to shofar blowing, share lighthearted moments in her garden, celebrate her miraculous recovery from COVID, and answer painful questions of her incarceration in Auschwitz, honoring her irrefutable testimony, as deep springs of pain bubble to the surface. It might have been 77 years ago, but the horror, and the lessons, can still be transmitted.

How 17-year-old Dov Forman has teamed up with his elderly great-grandmother to share her Holocaust testimony, Jewish values, and love of life with today’s generation via social media seems like the entwinement of strong yet time-worn fiber with spry, youthful strands. In person, however, I recalibrate. Lily Ebert is 97, but she has a youthful exuberance. Her bright eyes and generous smile make her seem almost young, as she holds her own at the center of a little gathering at her granddaughter's home in Golders Green, London.

Time to Tell

When Nina Forman — Dov’s mother — was just five, she innocently broke the silence by asking a question no one had asked her grandmother Lily before. “Savta,” she said, one evening, “What’s that? Why have you got blue numbers on your arm?” Mrs. Ebert brushed the question aside. “How could I possibly explain Auschwitz to a five-year-old?” She had raised her own children with no talk of her nightmare experiences in the death camp. The Holocaust, which had killed something within each survivor too, was an unspoken shadow in the family — questions off-limits.

But as a grandmother, in the framework of a Survivors of Shoah group in London, Lily learned to share her memories. In the late 1980s, with time on her hands after her husband’s passing, and with the realization that the past trauma would never go away, she eventually let the vivid scraps of memory which had been bottled up for so long emerge, and began to tell her story, finally fulfilling a promise that she had made to herself in the concentration camps. On two group trips to Auschwitz, to teachers, to school children, and to commuters in London’s Liverpool Street station, Mrs. Ebert unearthed the buried memories and shared them. She was not the only one; several friends who had survived the Holocaust wanted to create a group. Lily helped facilitate the Holocaust Survivors’ Centre in London, where the survivors could enjoy each other’s company. It’s a place where, in her words, “the soup is thick and nourishing, and we are served properly. There are no queues [lines]. There’s plenty of bread. Everything is clean and bright, nothing is painted yellow, and you won’t see any striped material anywhere.”

When COVID struck, Dov, Nina’s teenage son, noticed that Mrs. Ebert was restless. Visiting schools, meeting friends, playing bridge, and all social and speaking engagements were forbidden under the extended lockdown, although Dov did arrange one Zoom talk. And then, one Motzaei Shabbos, his Savta took out an old album. There were pictures of her family, some of herself immediately after the war, and a German banknote he’d never seen before. It was inscribed, “A start to a new life. Good Luck and happiness,” and signed with some Hebrew letters and the words “assistant to Chaplain Schachter.” Dov was curious: Who was this benefactor who had given her the note in the Displaced Persons camp set up in liberated Buchenwald in the spring of 1945? Mrs. Ebert, who could tell audiences the excruciating details of the hell of Auschwitz, couldn’t recall the name of the liberating GI who had given her the banknote with his best wishes. For Dov, it was a challenge. “Savta, give me 24 hours,” he said. “I’m going to find him for you.”

Tech-savvy Dov put out a Tweet that hit one million views, and it took just eight hours to find the family of Private Hyman Schulman in New Jersey. The social media storm the reunion created buzzed around the world. Rabbi Herschel Schachter, the first US Army chaplain to participate in the liberation of Buchenwald, announcing to the Jews that they were free, remained in the liberated concentration camp for months tending to survivors’ needs, and had arranged for Lily and her two surviving sisters to recuperate and begin new lives in Switzerland. Hyman Schulman’s good wishes were a touch of human kindness that Lily treasured for decades.

It was 8:30 on Sunday morning when Dov Forman, today a 12th grade student at London’s Modern Orthodox Immanuel College tweeted the picture of Lily holding the autographed banknote, tagging a few organizations such as the Auschwitz Memorial Museum. A few hours later, he had 8,000 notifications on Twitter. By 3 p.m. London time, as the East Coast of the USA woke up, there were one million likes, and a little over an hour later, someone made the connection to Private Hyman Schulman.

The reunion with Schulman’s children was a moving moment for the entire family. As the story snowballed, details of Lily’s ordeal came to light through historical documents and harrowing testimonies recorded and sent by other survivors.

Some of those documents and footage were invaluable. Like the video reel someone sent from the US Holocaust Museum about Rabbi Schacter’s travels, a section of which shows orphans of Buchenwald boarding a train for Switzerland. Working out the dates and comparing pictures the family had of a young Lily, the family spotted her on the reel, getting ready to board the train together with her sisters whom she protected during their time in the camps. Seeing the clip herself, Lily was shocked and amazed that footage actually exists of that surreal time in her life.

In the wake of the viral tweet, mainstream media came knocking to interview the survivor and hear the story of the banknote. Dov’s dream of harnessing the positive power of social media, using short clips to interest viewers, who would then follow through to the longer interviews, came true.

Somehow, in between his studies, he’s built up a 1.5 million TikTok following for videos about Lily’s Holocaust experiences and Jewish life. “Someone has to be out there, posting the good stuff,” he says, “and I’ve always been asking Savta questions.”

Followers of the duo send their questions to Lily, and Dov selects a handful every week for her to address on the next video clip. Most responses to Lily’s clear, candid messages are from grateful and inspired users, but with such a broad reach, there are also responses from the haters. Dov says that he gets hate messages daily from #Holohoax and other Holocaust-denier types, and as fast as he blocks the accounts, the troublemakers create new ones. But those are relatively few among millions of likes, and he tries to ignore them, definitely not reporting the worst of the comments to Lily.

She’s not unaware, though. “People say anti-Semitism is coming back, but that’s not true,” she comments. “It never really went away.”

We Didn’t Know What Was Coming

Dov is definitely a young master of 21st century communication, but I think their success hinges as much on Mrs. Ebert’s charisma and exuberance as her great-grandson’s savvy.

Lily was the oldest of six Engelman children, born in Bonyhád, a little market town in the Hungarian Oberland. Her father’s family had roots in the community stretching back a few hundred years, so that they were related to many of the Jewish townspeople. On Anyukah’s [Mother’s] side, Lily’s grandfather was Rabbi Breznitz, and her family tree shows their lineage all the way back to the Tosafos YomTov, Rav Yomtov Lipman Heller.

Like many Hungarian towns, Mrs. Ebert explains, Bonyhád had two communities, Orthodox and the more assimilated Neolog, with two separate shechitahs and cemeteries. Aharon Engelman was an Orthodox textile businessman, his four girls and two boys always beautifully dressed. Lily had a happy childhood, a loving family, strong faith, and sheltered middle-class upbringing. Even the chores were pleasant, she remembers — helping her mother prepare cakes and challah dough to be baked in the bakery oven — but her favorite memories are of Pesach.

“All our mother’s family, with lots of children, came to Bonyhád, and there was all this upheaval that we looked forward to the whole year. We had a separate tabletop for Pesach that was kept up in the attic, and two big boxes of Pesach meaty and milky dishes, so there was lots of fun, lots of going up and down. Every family had a day to bake matzah in the town’s matzah house, and we children stuffed our pockets with broken matzah pieces.”

Our chat about letcho, teyesh [milchig yeast dough], and the aroma of cholent that filled the streets of the little town on Shabbos morning when each family sent a child to the Jewish bakery to pick up their own steaming pot is so pleasant that it’s not easy to move our conversation forward to the dark days ahead. Yet Mrs. Ebert bravely delves into the dark memories, ready to share, no matter the heartache it re-awakens.

“The truth was,” she confirms, “that by the time the Hungarian Jews were taken to the camps, 75 percent of Europe’s Jews were already dead. Yet, we did not know what was coming. Back then, by the time you heard the news, it was history — and we didn’t have close family in Eastern Europe who would have reported to us.”

Lily heard about the outbreak of World War II as she stood baking round challahs in the kitchen with Anyuka on Erev Rosh Hashanah, 1939. Life in Hungary continued, though, and if there were vague rumors, nobody could believe them. The only disruption that Lily can recall is that a Jewish girl from Czechoslovakia was sent to live in Bonyhád for safety and joined her class.

In February 1942, Adar 5702, Lily’s father fell ill with pneumonia and died. As the eldest, Lily gave him her promise that she would help to take care of her younger siblings more than ever. Neither of them foresaw how this promise would be tested, and how it would haunt her from the day the two youngest were separated from her. We look in silence at a picture of the kever: Aharon Engelman was buried in the Orthodox cemetery of Bonyhád among his parents, uncles, and aunts. It’s clear that Lily feels this was his good fortune. “He was lucky he didn’t see what happened. He was one of the last to be laid to rest in Bonyhád. He could never have dreamed how life in Bonyhád would end.”

By the time the Germans invaded Hungary in March of 1944, they were already seeing defeat on several fronts. Still, exterminating all of Europe’s Jews remained a central objective of the Nazi regime. By then, they were experts at systematic extermination, and Hungary’s Jews were deported and murdered in an incredibly efficient process — between May and July 1944, over 434,000 Jews were deported, most of them to Auschwitz, where about 80 percent were gassed on arrival.

“Up to the last minute,” she remembers, “we could live relatively normally, and then suddenly it was over. Armed soldiers gave us one hour to pack and meet in the ghetto, the poorest area of town. They told us — and we believed them! — that we would be away for a few weeks or months, then go home.”

The Engelmans packed some practical items, like bedding and food, and, together with their relatives and Jewish neighbors, obediently took that short walk to the ghetto. Imi, Lily’s 19-year-old brother, a year her junior, ran to Anyuka’s room and grabbed her earrings and rings and Lily’s golden angel pendant. Lily fingers that tiny pendant now, on its gold chain around her neck.

“We think that’s the only gold that went into Auschwitz and left in the hands of its original Jewish owner,” Dov says.

Lily watched her brother as he secured their belongings. “Imi was training as a dentist. He brought his tools with, and as we gathered around in that small room in the ghetto, he asked Anyuka to take off her shoe. He removed the heel and packed the jewelry in, then closed it. I watched him. On the final day of our transport to Auschwitz, my mother suggested that we swap shoes. I put on her shoes and gave her mine. Normally, all shoes were confiscated, and prisoners wore wooden clogs, but for some reason, maybe because they had none left as the Hungarian Jews had been arriving by the thousands every day, maybe because we were one of the very last transports, they let us keep our shoes. I emerged from the showers to find my clothing taken, but Anyuka’s shoes were there waiting for me.”

Did Anyuka have a premonition that caused her to give the shoe with the family jewelry to Lily? Her daughter doesn’t know. What she does know is that her mother remained calm and composed, even on the horrific five-day journey that took her and her children to a destination so hellish it defies comprehension.

“I cannot describe it in words,” Lily says, pushing herself to express the horror of that journey. “Five days. Babies without food, mothers with nothing to give them. One bucket for water, one for human waste, the summer heat, the space so cramped that you could not move. My little brother Bela was 13, a very serious bar mitzvah boy. On the last day of that transport, which was Sunday, my mother felt a little food in her pocket, a crust of bread or a carrot maybe. She wanted the children to eat — we were all starving. But Bela had counted the days, and knew that Shabbos was Shivah Asar B’Tammuz, so Sunday was a fast. Bela said ‘No, Anyu, I will eat later, after nightfall. I have to fast.’ She couldn’t persuade him to put a little food into his mouth.”

This was July 9, 1944, the final day of the Hungarian transports. She remembers the blue sky and the seconds of relief as they could emerge from the stinking, fetid cattle car into the open. Then, stumbling out amid shouts of “Schnell, schnell,” barking dogs, and shaven stick people in striped clothing, they thought perhaps they were in a madhouse.

Still fasting for his first Shivah Asar B’Tammuz, Bela, together with the other children of Bonyhád, was separated from Lily. When Josef Mengele yemach shemo, with his polished boots and white gloves and a flick of the baton (“I see him still, but I see a blank instead of his evil face,”) pointed Anyuka, Bela, and 11-year-old Berta to the left, the three older girls — Lily and her sisters, Rene and Piri — had no idea that they would not see them again. It happened so quickly that they did not exchange even one word. The girls managed to stay together. “I didn’t walk anywhere without my sisters next to me,” Lily says of her months in Auschwitz and beyond.

Bewildered, the girls asked other Jewish prisoners what kind of factory this was. What was the horrendous smell and the strange smoke from the chimney? “They told us ‘those are your families.’ We said ‘You’re crazy. What are you saying?’ But very quickly we found out they were not crazy.” The Hungarians, who had been under illusion that they were being temporarily resettled for work, were the deluded ones.

We Were Worth Saving

A blue floral faded square of material lies near us on the table, neatly folded among the pictures and memorabilia. Mrs. Ebert’s granddaughters pass it over to her, and she opens it gently to a full square. “Flowers, in Auschwitz. They shaved our hair so we could barely even recognize familiar people. But one day an older cousin somehow recognized me and my sisters, and she gave us this as a present to cover our heads. She worked in the “Canada” section, where the clothing and possessions of the deported Jews were sorted and searched for valuables, and I also worked there for a week.”

Although she has told her story so many times and in so many forums, Mrs. Ebert considers each question carefully. Sometimes she looks pensive and thinks carefully, at other times, she volleys back an answer instantly. There are some details she no longer recalls, she admits, but most images are indelible.

She notes that since the Hungarian Jews were the most recent arrivals, the men could keep track of the Jewish calendar. On Rosh Hashanah, the Hungarian girls found some pages of a siddur, which they passed around so they could pray. And on Yom Kippur, they fasted — there was no question.

“The men were on the other side of the electric fence, but sometimes you could speak to them. The men worked out which day it was, and we fasted. I saw one Polish man, and he was eating, so I asked him, ‘What are you doing? Today is Yom Kippur!’ He said to me, ‘Magyarteh [Hungarian woman]! How long are you here? If you were here as long as me, you would eat too. Believe me, I have fasted enough.’” Lily is crying now. “He was right, I was wrong, I shouldn’t have said anything.” She remembers that the SS guards sadistically chose Yom Kippur as a date for horrifying selections.

Fear and hunger consumed all thoughts. The girls spoke about challah, and Yom Tov food, and compared how their mothers used to prepare chicken paprikash. Mostly, though, they longed for bread. Lily tried to protect her sisters, especially Piri, who was only 15 and very skinny. She remembers the dehumanization, the manic cruelty that denied the Jewish inmates any privacy, any choices, starving and terrorizing them with selections and harsh punishments. She tells us about some who did not want to eat the nonkosher food, and died of starvation, like Malkaleh, a girl she knew, or the father of a friend. “He made his son eat, but could not touch the soup himself. He died. The son survived.”

Once, Rene was selected for death. She automatically followed orders and started moving forward, but Lily pulled her back by the hand. Once the guard had given his orders, he assumed they would be obeyed, and didn’t look back to see if anyone stepped out of the line.

When the sisters were marched to the ‘A’ Lager and stood in rows of three to be tattooed, Lily recalls that it was actually a sign of hope. She shows us the number, A-10572, faded, but very much there. “It was good quality ink! And that is what gave us hope. We realized that they wouldn’t waste it on us if we were to be killed instantly. It meant we were worth saving for a bit of work.” Her sisters, on either side of her, received numbers A-10571 and A-10573, and they were among a group of 500 girls taken to work in a munitions factory in Altenburg, a sub-camp of Buchenwald in Germany.

“It seemed like a five star hotel when we first saw it. Toilets, in cubicles with doors! And showers (although no soap or towels)! But the 12-hour shifts of heavy work, day and night, the cold and the tiny rations of bread, weakened us still further, until many people could not survive any longer.”

Anyuka’s shoes had worn out in Auschwitz. “So where did you keep the jewelry?” I ask.

“Good question! I hid it in the bread. We got a daily piece of bread, which we never ate right away, but kept until we got the next slice. Each day I made a hole in mine and stuffed the gold and diamonds inside. In Altenburg, I sneaked some material and made a tiny pouch.”

It was on a death march from Altenburg that bombs exploded on the road near the column of starved women, and they suddenly saw tanks of the United States military.

“Did that take you by surprise?” I ask.

“They were more surprised to see us,” Lily retorts. “We were almost unrecognizable as people, never mind young women and girls. The SS guards knew how to disappear. We were free. The American soldiers did not know what to do with us. They were trained to fight, not to take care of people. But they were kind.”

Within a few weeks, the girls were in Buchenwald, this time as Displaced Persons under Rabbi Schachter’s charge. The rabbi offered Lily, Rene, and Piri the chance to go to Switzerland, and that’s when one of his assistants gave Lily a banknote with the now-famous message. Lily remembers, “It was the first spontaneous human kindness we’d experienced for a long, long time.”

We Need to Finish

There was a selection of organizations ready to take responsibility for the group of orphans who came to Switzerland. Lily chose to go with Agudas Yisrael to their girls’ hostel in Engelberg.

“Zionism was not a big thing in Bonyhád. I knew that my parents would want us to be in the care of the most religious organization there, and I knew that my sisters and the other girls I was with would come with me, so I chose the Agudah,” Lily says and then confides, “I made the right choice. Rene and Piri both married and settled in Bnei Brak.”

After a year of recuperation amid Alpine beauty and fresh air, which was also a year of waking up to the loss of her family, home, nationality, possessions, familiar language, and hometown, Lily decided to move to Eretz Yisrael. Lucky enough to get immigration certificates to Mandatory Palestine, the small group of Hungarian girls began new lives in Tel Aviv.

Her husband, Shmuel Ebert, had arrived in Israel from Budapest in 1938. After those years of taking care of her sisters, Lily had found someone who would take care of her. “To have someone who knew exactly what he was doing come along and take charge felt like a blessing,” she says.

In 1953, Lily and her sisters were reunited with her brother Imi, who had survived the Hungarian slave labor camps, then gotten stuck behind the Iron Curtain. The Eberts, with their three children, moved to London in 1967.

Today, Lily Ebert feels the need to complete her mission as one of the few remaining survivors who can still give a live testimony to one of the worst atrocities in the history of mankind. She encourages her young viewers to ask any questions they have, even though they might not want to cause pain and dredge up difficult memories. If they don’t ask now, she says, later there won’t be anyone left to ask. And so she bravely answers all the questions that come her way, even though until a year ago, social media was a foreign concept. Today, coached and accompanied by her enterprising great-grandson, she’s gotten the hang of making short clips in front of the camera.

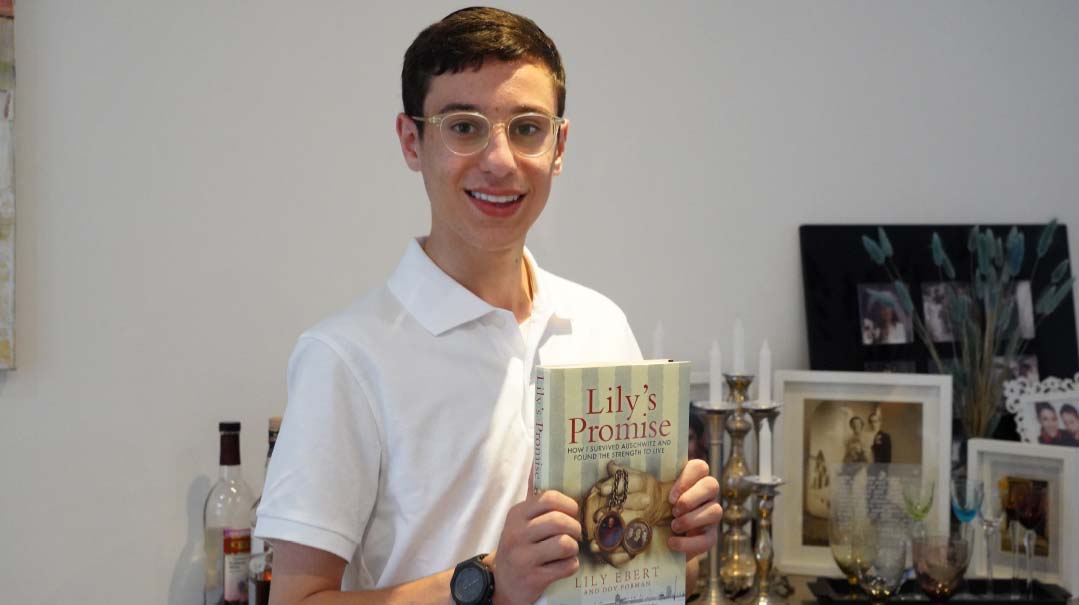

Following their social media success, Lily and Dov closed a deal to write a book together. The title would be Lily’s Promise. They immediately set to work, but a few months in, it looked as though the book would never happen: Lily had contracted Covid-19.

Lily was bedridden for almost a month, while Dov kept her million-plus social media fans updated on her condition. But she rallied, and as soon as she was up and speaking again, she told Dov, “We’ve got to finish the book.”

In the month since it’s hit the shelves, Lily’s Promise has become a best-seller. Dov even elbowed his way through to get a foreword written by H.R.H. Prince Charles, the next in line to the British throne. (In 2015, Lily was awarded the British Empire Medal (BEM) for services to Holocaust education and awareness.)

As we say our goodbyes (Lily and Dov have to get to their next engagement, a scheduled book-signing in the nearby mall), Lily graciously autographs a copy of the book for me. For her, the stories inside are a backdrop to the page she shows me — a collage of pictures with her multi-generation family of grandchildren and great-grandchildren, her real living legacy. When the photographer takes the opportunity to ask about how she kept her emunah alive, she basically shrugs off the query: For her, she says, it was never a question. And maybe that’s the eternal lesson this brave, petite survivor is passing on to her young audiences: among the myriad quickie entertainment clips, a message that resonates forever.

Straight To The Heart

Here is a tiny sampling of the thousands of responses Lily and Dov receive on a regular basis:

I hope she realizes how much she is teaching others with her words and her experiences.

Lily you make me smile when my days are bad.

Shanah Tovah! I haven’t heard the shofar in such a long time — thank you for sharing this precious moment!

The look of joy on your face as he blows it! It’s so beautiful to see how you kept your Jewish heritage after the Holocaust when so many couldn’t.

The joy you exude and wisdom of your life, despite such atrocities, makes me feel that we will celebrate all that is good, forever.

Their faith was as important as a chance at a rare piece of bread for survival. Your videos have taught me so much.

Imagine to be willing to give up your only food ration to lay tefillin. She’s talking about giants of Judaism. And humanity!

I have just put on tefillin because of your video.

Your video inspired me to light the Shabbat candles.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 881)

Oops! We could not locate your form.