Declaration of Independence

Can Yoeli Landau’s recipe for success reset the troubled relationship between Israel’s chareidi population and the state?

Photos: Abe Kugielsky

EXCLUSIVE!

Satmar patron and nursing home magnate Yoeli Landau retraces his journey from struggling student to poverty-stricken yungerman to steward of a vast financial empire and visionary giver. Can his recipe for success reset the troubled relationship between Israel’s chareidi population and the state?

“Yoeli Landau, who asked for your opinion?”

“Yoeli, why do you fly around in a private jet?”

“Yoeli, why do you think you can send the Gerrer Rebbe a letter preaching your ideological views?”

These are just three of many questions that hummed in my mind as I reached out to the philanthropist who’s captured headlines and conversations in recent months.

Yoeli Landau, a Satmar chassid in his mid-forties, represents a young generation of chareidi moguls who aren’t looking to hide — not their affluence, and not their religious identity. After a rocky start in life, he built a fortune in the nursing home business, and promptly began to dispense vast sums of money toward a multitude of projects and tzedakah causes.

Yoeli’s grand deals, appetite for risk, and lavish generosity tend to keep him in the news: be it the mainstream media, business sites, or the less official but often more passionate heimish news circuit. He sees the blessing of money as the fruit of a mentality and ideology, which, he says, enables him to dedicate more than 50 percent of his immense income to tzedakah.

In the last year, his financial success has also granted him a rare role: advising some of the chareidi world’s leading rabbanim and admorim on perhaps the thorniest issue they face. Some justify this new advisory role as a privilege that comes along with the territory of mega-wealth. Others are harshly critical — “Your job is to give, not to guide.” Some appreciate what he is doing and others feel a decided discomfort with his very public persona. The common denominator: When it comes to Yoeli Landau, everyone has an opinion.

As for Yoeli himself — the rising chassidic baron from Williamsburg, with his long curled peyos, woolen tallis katan, and slightly bashful smile — he hardly seems affected by all this talk. While the dust is settling around yesterday’s headlines, he’s already on to the next big thing.

From my experience over 18 years of writing, I can describe three types of people who tend to give interviews. The first type seeks influence. The second wants exposure. The third wants prestige.

Yoeli Landau doesn’t need any of these. So I wasn’t surprised when he refused every one of my interview requests over the last few years. “Ess felt nisht ois, I’m not lacking publicity,” was his response.

But this year, I had a rejoinder. “You can’t rile up the entire chareidi public with provocative letters and public demonstrations of influence and then disappear into your offices on Third Avenue in Manhattan. You owe the public answers,” I told him. “If you dared to send a letter to the Gerrer Rebbe advising an ideological shift — then the tzibbur has some serious questions to ask you. If you stand up at an event distributing seven million dollars to institutions that do not benefit from Israel’s government funding, and you take advantage of that event to preach to all of chareidi Jewry to join the Satmar ethos — as if they don’t have their own ideology and they need a Williamsburg magnate to come and give them mussar — you owe the public some answers. It’s not enough to declare your distaste for the Zionist state. People have real questions, and this is your chance to answer them.”

At this point, he softened. He liked the argument.

And so I boarded a plane and spent a few days getting to know the fascinating chareidi phenomenon known as Yoeli Landau. My tough questions yielded surprising answers. The man behind the headlines was different from what I expected.

There was bashfulness. Seriousness. Idealism and an earnestness almost akin to naiveté. It’s hard to believe that someone who handles so many millions could be suspected of naiveté, but apparently Yoeli Landau maintains a strict demarcation between his business persona and his spiritual self. You can see it in the way his eyes sparkle when he shares a moving quote he unearthed in an early chassidic sefer — it seems to excite him more than closing a multimillion-dollar deal.

Turns out, the story of Yoeli Landau is the story of a child from Kiryas Joel with severe ADD, a child who was written off by every rebbi in the cheder and rejected by his peers. He didn’t believe he would ever amount to anything — until one dedicated rebbi turned things around.

It’s also the story of a poverty-stricken yungerman without a dollar in his pocket who slept on a shul bench like a homeless vagrant, just to qualify for governmental housing assistance. Until he decided to escape a life on the dole — and became one of the most generous chareidi billionaires of our times.

Threaded through the story is a strand of firm, unflinching bitachon — the type of trust that fortified him to forego a 900-million dollar deal so as not to perform melachah after chatzos of Erev Pesach, and another 2.3 billion-dollar deal on Chol Hamoed.

After spending a few days with him, watching him in action in settings as varied as his Williamsburg vasikin minyan and his business offices in a Manhattan skyscraper, these are the impressions of my journey.

Yoeli Landau — the full story.

The Night It All Changed

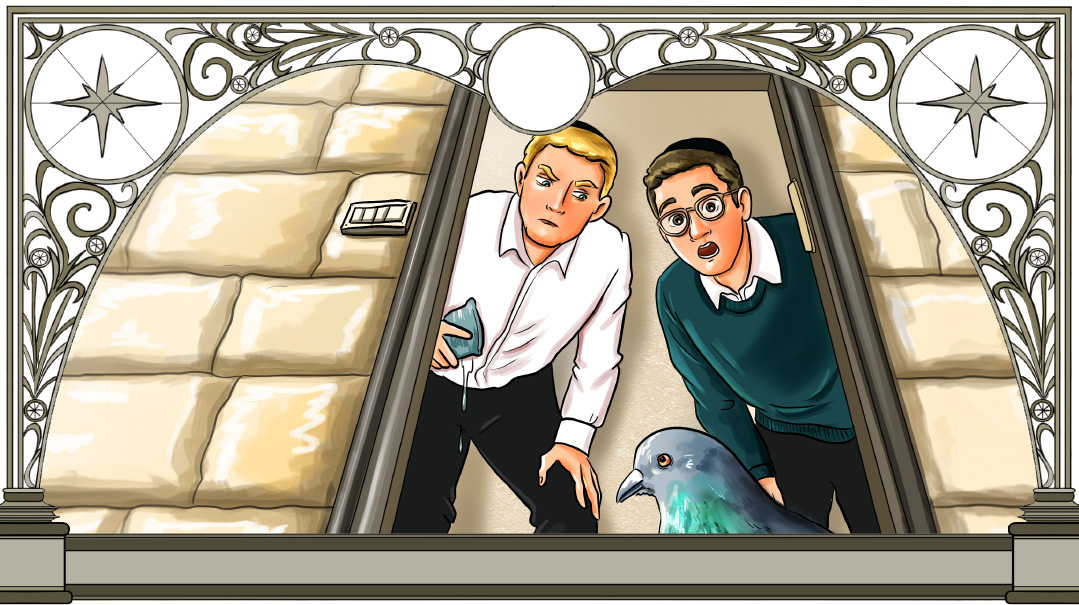

On Motzaei Shabbos Parshas Bamidbar 5785/2025 — just one night before Shavuos — rumors began swirling through Jerusalem’s Gerrer court. A regal black Cadillac outfitted with flashing lights had slipped into the parking lot outside the Rebbe’s home. Who could it be?

“Yoeli Landau is going in to see the Rebbe,” whispered those in the know. The young Satmar philanthropist from Williamsburg had been invited to take a seat in the elderly Rebbe’s inner chamber, at a table where crucial decisions are made for Israel’s largest chassidic court. It was an encounter that, in other times, would seem utterly fantastical.

But these were not regular times. The chareidi public had been put on the defensive, with the threat of a forced draft hovering over the heads of tens of thousands of bnei yeshivah, and suffered significant funding cuts as per the directives of the hostile attorney general, an oppressive legal system and a hamstrung Knesset.

Despite his advanced age and precarious health, the Gerrer Rebbe resolved to travel to America in an effort to open the hearts and pockets of generous donors there. Surely when these philanthropists would see the Rebbe straining to make his way from home to home, they would understand just how dire the situation was, and contribute accordingly.

The Gerrer askanim were stunned by the decision. It had been some years since the Rebbe had traveled overseas, and in order to ease his journey, they were determined to find a private plane.

So how does one obtain a private jet in 48 hours? All fingers pointed to one chareidi philanthropist who’s a passionate defender of Yiddishkeit. And what began as a technical request for a private jet became, within a few hours, an unusual meeting with potentially historic reverberations.

A meeting between Gur and Satmar is in itself noteworthy. How did it come about?

“When the Gerrer askanim reached out to me, at first I declined,” Yoeli admits. “‘What do I have to do with Gur?’ I asked them. ‘You have your shitah, I have the one I was raised with — I’m not sure this shidduch is going to work.’

“But then,” he reveals, “I received a call from the Rebbe’s son, who said this was not about help with funding and for the plane, but rather an interest in hearing the advice of an experienced businessman in the face of the serious crisis being faced by Torah and chassidishe mosdos. ‘Come and see the Rebbe and you will be zocheh to hear things, and to say things, bakodesh penimah,’ was the suggestion.

“Hashem had arranged it that I was in Eretz Yisrael at the time,” he says. “And so, on Motzaei Shabbos, I went to Rechov Yirmiyahu and sat — for the first time in my life — in the presence of the Gerrer Rebbe shlita.”

There followed a rare conversation in the Rebbe’s house lasting almost 22 minutes, which is most unusual in Gur. The people of the Rebbe’s household and the askanim were not present.

“As we spoke,” Yoeli remembers, “the Rebbe said: ‘They [the government] keep promising there’s going to be an agreement to safeguard the status of the bnei yeshivah, but there has been no progress. They are ligeners, liars. What do you think we can do to resolve the crisis?’

“In response, I asked the Rebbe, with submission and awe: ‘Men ken ales redden? Can I speak openly?’ The Rebbe said: ‘Aderaba, lomir heren, let’s hear.’”

Landau spoke very directly: “In my humble opinion, the battle over the draft is a spiritual one — a milchemes kodesh that has nothing to do with politics. That’s why the chareidi politicians keep failing to sort it out. I have humbly come to say, in the name of Klal Yisrael: Klal Yisrael needs the Rebbe’s direct hashpa’ah. Perhaps the matter should be taken out of the hands of the chareidi politicians.”

Yoeli then referenced the time, 20 years earlier, when the Rebbe himself had taken on the cause of kosher cellphones. Now as well, he said, the tzibbur needed the direct leadership of the Rebbe, without politicians serving as intermediaries.

The Gerrer Rebbe looked at him. “Nu,” he said, meaning, “tell me more.”

Yoeli accepted the invitation and began to speak, with great passion, about a worldview shaped by both his Satmar upbringing and his business experience — a perspective that welcomes Divine abundance even as it eschews dependence on others. And by others, he means not only welfare programs and handouts, but the official budget allocations of the State of Israel.

A few days later, Yitzchak Goldknopf, the Gerrer representative on the Agudas Yisrael slate, resigned from his position. And on that day, Yoeli received a telephone call from the Rebbe’s son Rav Nechemiah. “The Rebbe asked me to let you know that he enjoyed your explanation of how American commerce works and what one can learn from this about our own situation, and we are progressing with the plan. People are pressuring us not to leave the government, but the Rebbe is determined that this is the correct course of action.”

Yoeli Landau — maverick nursing home entrepreneur, generous baal tzedakah, ambitious implementer of projects and campaign — had found a new role.

Public Persona

Yoeli Landau is a 45-year-old chassidic billionaire famed for his flamboyant initiatives — be they business acquisitions, construction projects, or tzedakah campaigns. But while his actions often make headlines, in person he’s shy and uncomfortable in the limelight. In fact, he’s only given a public address twice in his adult life.

The first time he spoke in public — after extensive preparation and lots of urging from many people, including the Satmar Rebbe himself — was less than a year ago, at the huge event that Satmar holds each year on 21 Kislev at the Brooklyn Armory. Landau stood there on the dais behind the Satmar Rebbe and all the rabbanim of the chassidus, and delivered the speech of his lifetime to thousands of chassidim.

With his speech, Landau burst out not only onto the public stage, but also into Satmar’s high-ranking echelons of askanus and commerce.

The second time he appeared in public was on 26 Av of this year, the yahrtzeit of his namesake the Satmar Rebbe ztz”l. Landau was sent to Eretz Yisrael by the Rebbe Rav Yekusiel Yehudah (Rav Zalman Leib) of Satmar in support of the mosdos that do not take funding from the State. He came with his wife’s grandfather, Reb Chaim Yechezkel Stein, one of the meshamshim of the Divrei Yoel, to inaugurate a multistory building of the mosdos on Rechov Yechezkel in Jerusalem, of which Yoeli is a primary donor.

As is Landau’s wont, the event was celebrated with elaborate pomp and ceremony — including a hachnassas sefer Torah featuring horses and elegant carriages. During that visit there was also a distribution of the “shekel hatahor” — envelopes with funds for the heads of the mosdos who do not take government funding. There, Landau delivered the second speech of his life — affirming Satmar’s approach of “lo midvushech ve’lo m’uktzech” — a refusal to accept both the honey and the accompanying sting of the Israeli government’s handouts.

“Here we are, Rabbeinu!” Landau announced, referring to Rav Yoel of Satmar’s shitah. “To the Zionist State, we say — no thank you! We invite all the kehillos of chareidi Jewry to join our shitah.”

The previous generation of Satmar philanthropists may have been gratified by big placards with lots of curlicues and honorifics, but Yoeli Landau is uber-practical, and poetic signs and brachos don’t talk to him. “Those things really embarrass me, and you won’t see my name on buildings,” he says.

But even though he works behind the scenes, he dominates conversations from Williamsburg to Bnei Brak. There are those who admire what he does, while others see him as an egocentric gvir who doesn’t quite understand the limits of his role and place.

But even those less enamored of his style — and there are many — admit that he’s the type of gvir that does not keep his wealth to himself, and uses his abilities and influence to benefit the public.

When it comes to his public projects, Yoeli aims for klal-level impact. He’s involved in an array of projects — from yearly multimillion-dollar pre-Yom Tov distributions to needy families in Williamsburg, managed by his brother, Reb Motty; to the establishment of heichalei Torah in New York and Jerusalem, supporting yeshivos for older bochurim in Israel and abroad, serving as a patron of the Mesivta edition of Shulchan Aruch published by Oz Vehadar (to date, 100 volumes have been released, and the expectation is that the edition will reach 250 volumes), and many more sensitive initiatives that assist couples struggling to have children, along with a campaign encouraging people to refrain from speaking during davening.

This last campaign is named Keren Tosfos Yom Tov, in the name of the commentator of the Mishnah, Rav Yom Tov Lipman Heller, who composed the famous Mi Shebeirach for someone who guards his mouth from speaking during davening and Krias HaTorah. Recently, Landau even launched a children’s Yiddish newspaper entitled Shtender’l, which explains the importance of being quiet in shul. There are 50,000 Yiddish-speaking children in America who have joined the initiative.

In recent years, Landau also built four wedding halls for families who agree to adhere to the wedding takanos instituted in the larger chassidic courts to help reduce costs. The cost is $5,000 per side, including all the expenses of the wedding night — music, photographer, flowers, and badchan. Two of the halls are in Williamsburg and two are in Kiryas Joel, the Satmar enclave headed by Rav Aharon of Satmar. It’s an artful move by someone who’s mastered maneuvering between the two Satmar courts — the one he belongs to, headed by Rav Zalman Leib, and the one that he also admires, headed by Rav Aharon.

One of the guiding principles in Yoeli’s life is his pride in being visibly chareidi and chassidish. “I meet with leading businesspeople in the world, modern Jews, and l’havdil non-Jews — and I come with the azus d’kedushah, pride in my spiritual standards. They see me with my curled peyos, with my wool tzitzis, my insistence on davening with a minyan, and with my shemiras einayim. And I can tell you: Not one of the boundaries I have placed on myself ever led to a loss of money — in fact, the opposite is true. When people see that you’re an Orthodox Jew, with principles, you make an impression of being reliable and trustworthy and everyone wants to do business with you.”

In recent years, as he’s become more well-known, young people began to approach him and ask for business tips. The first tip he shares: “Don’t relax a single one of your spiritual principles. That is the real key to success.”

Landau Gimmel

But Yoeli started out life in a far less privileged position. To fully understand the phenomenon of Yoeli Landau, you’d have to go back in time to Kiryas Joel of 35 years ago, to the miserable existence of a social outcast and academic failure rejected by his rebbeim and peers.

Yoeli was born in Monroe on 10 Elul 5740/1980. His father is Reb Yosef Dov Landau, a Yid who worked hard for his parnassah all his life. Yoeli was the type of child who drew headshaking and clucks from the adults who wrote him off as a failure.

“I was the weakest boy in the class,” he admits, his voice low, the pain still evident. “Thirty boys. and I was at the bottom. I didn’t understand anything in the Gemara — the melamed would start to explain, and within seconds, I was lost. Today, we call this ADD. Then they just called me ‘the boy who couldn’t learn.’ I didn’t have much interest in the games we played at recess either, so school was just full-time misery.

“It didn’t help that I come from a family of high achievers. My brothers were bright students who also did well socially. I felt like I was always left behind. Today, my melamdim from my childhood tell me, ‘Reb Yoel, I never would have believed that I’d see you this way.’”

Yoeli’s worst trauma occurred just before his bar mitzvah. “There were lots of boys in the class named Yoeli — we were all born the same year, right after the passing of our Rebbe, Rav Yoel of Satmar zy”a. Not only that, there were four kids in the class named Landau, so we had three Yoeli Landaus, and I was the weakest of them all. They called us Landau Alef, Landau Beis and Landau Gimmel — I was Landau Gimmel.

“One day, the pay phone rang in cheder. On the line was the mechutan of our rebbi, who apparently wanted to finalize some things ahead of the wedding. At the time, you will recall, there were no cell phones. One of the boys in my class picked up and when he heard that they were looking for the melamed, he decided to pull a terrible prank: He spoke horribly about the melamed, this caller’s mechutan. He said the most terrible things in an extremely disrespectful way. When the mechutan asked who he was, he said Landau Gimmel.

“A few minutes later, the melamed stormed into the classroom. It was obvious he was furious. He called me over, took off his belt, and whipped me viciously. It was two weeks before my bar mitzvah.”

Yoeli pauses. “Even today, when I remember this, I feel the physical pain. Worst of all: My mother, who heard the story from the rebbi, initially believed him. The rebbi was sure it was true, so my mother had no reason to think otherwise. I was thrown out of cheder, and I had to switch to a cheder in a different city.”

Yoeli’s stained reputation accompanied him to his new cheder, where he was the target of every suspicion. “When a boy realized his money had been stolen, everyone suspected me — the strange boy who had come from a different cheder with a problematic history. I couldn’t handle this darkness. I broke down,” Yoeli says. “I literally couldn’t stand myself.”

Then came the rebbi who saved his life. “That rebbi was amazingly sensitive, and he called me over and told me he wanted to learn with me. ‘But I don’t understand anything!’ I told him. But he said, ‘That’s fine, we’ll start line by line, slowly and calmly, without any pressure.’

“This was during Shovavim. The rebbi took me to his house and learned with me with infinite patience. Suddenly the gates of Torah were opened to me! I began to understand the Gemara and to taste the sweetness of learning. All I wanted to do was learn more and more. For the first time in my life, I felt fulfillment, achievement, simchas hachayim.”

Yoeli continued learning seriously and fruitfully for the next few years. And he maintained his connection with that lifesaving rebbi. “These days, his son actually teaches my children,” Yoeli says, “and I bought that son an apartment in the building where I live. It’s just a drop in the bucket of what I owe him. I truly admire him and his father as Yidden who are filled with Torah, yiras Shamayim, and most importantly — sensitivity.”

The admiration and gratitude led Yoeli to initiate an unprecedented step: at a speech he made at the annual Satmar celebration of the Rebbe’s rescue from the Nazis, he announced that all educators in the dozens of Satmar educational institutions would receive a permanent 30 percent raise in their salaries, which he committed to shoulder.

The move was met with tremendous admiration. “But I didn’t do it for the applause,” Yoeli says. “I did it because I know that if not for the melamed who believed in me, I wouldn’t be here today. I wanted every mechanech to know that they hold up our world.

“And honestly, a thirty percent raise isn’t enough. You can’t set a price for saving a child’s neshamah.” Now, Laundau addresses mechanchim who are reading his words: “Yes, yes, you, the melamed in the classroom. Each one of you have your special Yoelis. You don’t know what they are going through. They’re going through life without friends, without any sense of achievement, with terrible self-esteem. Remember, the rebbi who took me on as a project — he had no idea what would become of me. He couldn’t have known I’d succeed in life. He definitely didn’t dream I’d one day have the means to be on the giving end. He saw a rejected, nebachdige child and decided to lift him up. The rest, HaKadosh Baruch Hu took care of.

“So I’m pleading with you: Invest in the rejected children who are on the margins of the class. Take that child on as a personal project. It’s tempting to pay attention to the successful, obedient children, but that’s no big deal. Make an effort to invest in the hyperactive child, the struggling one. You will build him for life.

The Yungerman Who Slept in Beis Medrash

Though Yoeli had reached a better place when it came to his learning, his married life started out with more challenges. His wedding, to a daughter of Reb Yisrael Moshe Stein, the son of Rabbi Chaim Yechezkel Stein (known in Satmar as one of the meshamshim of the Vayoel Moshe) was held in an old chesed hall. The parents of the new couple hosted sheva brachos in their homes, as they could not afford to rent a hall.

“That was our lifestyle. We were used to it and didn’t expect anything different,” Yoeli says. “I started married life with $1,050 to my name — a thousand dollars from a modern cousin who brought a nice check to the wedding, and fifty dollars from someone else. That was it. The first week after the wedding, we had to deal with an unexpected expense of $6,000, and I had to take a loan from a friend.

“A few weeks passed and I saw that I wasn’t going to be able to pay him back. I realized I had to do something, find some way to make money, so I went to a photocopy store, and I printed and laminated a bunch of Birchas Hamazon cards. Then I put them at the entrances of a few Williamsburg shuls along with a collection box. Every night I came to collect the money that had accumulated, to pay back my debt.”

As a kollel yungerman with no income, Yoeli registered for all kinds of government programs in order to subsist. “At the time, there was a special support stipend for the homeless,” he remembers. “In order to get approved for this assistance, municipal officials came down to confirm that you had no home to sleep in. So I slept in a local shul for a few nights. When they saw me sleeping on a bench in the beis medrash, they approved me for rental assistance. I was thrilled.”

Yoeli says he’ll never forget those nights — he still remembers which beis medrash he slept in: Spinka, on Bedford Avenue.

Yoeli realizes that I’m skeptical about this story. “You don’t believe me? Here’s the phone number of a yungerman in Williamsburg who remembers it. Ask him.”

I dial, introduce myself, and ask the yungerman, a Spinka chassid named Reb Yoel Spitzer, if it’s true that Yoeli Landau used to sleep in his beis medrash on Bedford Avenue.”

He confirms that it is in fact true.

“I hope you believe me now,” Yoeli says.

Knowing where Yoeli Landau is today, financially, the story sounds delusional: A young man wrapped in a tallis falls asleep on a cold hard bench between piles of seforim, just to get a few hundred-dollar stipend from the city.

“I got every type of benefit there was,” he affirms, and it’s unclear if there’s a spark of mischief, pride, or shame there — but the authenticity is clear.

Turnabout in the Doctor’s Office

The breakthrough in Landau’s life that led him from abject poverty to fabulous wealth began in a doctor’s office.

“When my oldest son, Yidel, was a baby, we once took him to the doctor and waited an unreasonably long time until he saw us. It was a very irritating situation. When the doctor finally called us in, I grumbled — in my broken English — about the long wait. ‘What’s going on? How can you treat your patients this way? Why do we have to wait so long?’

“The doctor apologized and told me there was a reason for the wait, but it wasn’t something I would understand.

“I was curious, and I also felt that there was some injustice at play. So I pressed the doctor to tell me what the problem was. Finally, he gave in and explained that while he had plenty of patients, more often than not they had government-issued Medicaid health insurance, and the payments either weren’t approved, took months to arrive, or were very low. ‘The only way I can make any money here is to take patients who pay privately, or with better insurance,’ the doctor said. ‘So I fill up my daily schedule with as many of those as I can.’”

That was the minute when Landau’s entrepreneurial sense was sparked. He realized that there was a problem that could be solved here — and maybe also a bit of parnassah to be made. “I told the doctor, bring me all those rejected claims.’ He looked at me like I’d fallen from the moon. ‘Why do you need them?’ he asked, and I told him that I wanted to approach the relevant government offices and collect all those payments they had denied.

“The doctor literally yelled at me, ‘You don’t even know English! How are you going to figure out something that no one else has managed to do? Go home and take care of your baby.’

“But I insisted, ‘What do you care? Give me a chance!’ and he gave in. He asked the secretary to give me a whole pile of files with outstanding claims.”

Landau, who could barely produce a sentence in proper English, took the files and set out on this mission impossible. The work was very technical and complicated. He studied the ins and outs of the medical billing system and asked friends to help him decipher the forms. Then he contacted a friend who knew a high-ranking clerk and arranged a meeting. “I was determined to prove myself,” he explains. “I wouldn’t give up until I reached the person who could actually approve the payments. I tracked down a cousin, even involved a congressman… a whole story, all from Shamayim.”

One month later, he returned to the doctor with a check for 90,000 dollars. The doctor could scarcely believe his eyes.

“I was twenty at the time, a yungerman who didn’t speak English. I lived in an apartment that was half-underground, which I paid for with rental assistance, and suddenly I was bringing the doctor a fat check for all this money he’d given up on ever receiving.”

The next day, the doctor called Yoeli and said, “You have to help my friends, doctors also. They have the same problem.”

Yoeli used his new connections and learned the business. He fought for the doctors, and took a small percentage of the payments he won them. Slowly he began to creep out of poverty.

Things looked promising enough that he eventually decided to take a courageous step — to stop taking all the welfare benefits that New York offered the needy. “I decided that from that point on, I was no longer needy,” he says with a determination that still resounds a quarter of a century later. “I told my wife: ‘We’re going to stop taking government handouts and we’re starting to earn our own living.’”

Mrs. Landau tried to dissuade him: “It’s not a good idea to do it all at once. Start small. You’ll earn here and there, and slowly, you’ll cut off the support, gradually. Don’t cut off all our financial oxygen, it’s too risky.”

But Yoeli was determined: “I told her, no! As long as I’m a schnorrer relying on government support, I won’t succeed in life. I’ll be stuck in a rut, a needy person who lives on handouts. As long as I remain enslaved to that self-image of a needy taker, we’ll never succeed in breaking free.”

She agreed and the Landau family set out on a new path.

Yoeli pauses here a moment. “You’ve had a chance to get to know me enough to know that I’m not telling you this for no reason. It’s a real story, and there’s a message here. It’s a philosophy that has guided me from that point on, and for the rest of my life: Dependence generates weakness; independence generates strength.”

Yungerman, Learn English!

Yoeli’s medical insurance gig began to grow. One client brought another, doctors spread the word to their colleagues, and soon it became a routine: Yoeli Landau, aged 20, spent his days running around from clinic to clinic, collecting insurance claims and then visiting the city offices.

“One day,” he smiles at the memory, “my wife looked at me working hard in the little living room and said, ‘Yoeli, you have to believe in yourself and think bigger. Don’t keep your dreams locked up inside our dining room. Go rent an office, and start building a real business.’ I wondered if she just wanted a clean table! But I followed her suggestion and rented an office. Since then, I’ve never worked from home.”

Then he gets emotional, and tells me, “I must tell you that without the confidence she gave me, without her inspiration, without her faith in me — I would not have taken even one step forward. All the credit is hers. She’s not just a rebbetzin, she is my partner, my compass, and my courage. She keeps pushing me to believe that what looks impossible is actually possible, as long as you have emunah and bitachon.”

And he needed all the encouragement he could get. He remembers one Jewish doctor who told him in his face: “You’re making a big chilul Hashem! Not every young man with a beeber hit [a flat velvet hat worn by Satmar chassidim in America] and a long coat can be a businessman. Go take some English lessons and stop making a chilul Hashem.” The criticism stung, but Landau didn’t give in.

“Ten years later, the same doctor approached me because he wanted some services through the insurance company I’d established. He wanted to speak to the CEO. When I took the call, I said to the doctor, ‘It’s me, the yungerman with the beeber hit and the long coat. Remember me? You should know that I still haven’t taken any English lessons.’”

Doctors from the modern Orthodox community were not the only ones to laugh at the young and ambitious Landau. He remembers a chassidishe gvir from the older generation who he encountered when he was just starting out in business.

“It was the first private home I had ever been in,” Landau relates. “Until then I was only familiar with apartments or multifamily homes, the type that I grew up in and in which most of the community in Williamsburg and Monroe lives in. I had come to ask him for some business assistance. And he said to me, ‘Yungerman, learn English and then come back to me.’”

Yoeli’s English never became perfect, but he managed to segue into the lucrative nursing home industry anyway. His transition to this field was marked by clear Hashgachah pratis: His mother was originally Israeli. Her father, Reb Nosson Fried, was very close to the Chazon Ish, and was a well-known talmid chacham in Bnei Brak who was an expert in rare halachos, such as eiruvin and terumos and ma’asros. When he got older and needed full-time care, he moved into the Vizhnitz nursing home in Bnei Brak.

“One day, my mother called and said she’d be very happy if I could travel to Eretz Yisrael each month for a few days to visit Zeide Fried and cheer him up. I agreed. I didn’t have anything much better to do. I came to Eretz Yisrael once a month after that.”

It is doubtful if anyone in the nursing home on Damesek Eliezer Street in Shikun Vizhnitz knew that the American yungerman who was nudging the geriatric care staff would, in a few years’ time, become a titan in this very industry. But there is always a Divine plan: “During the period that my grandfather spent in the nursing home, I began to take an interest in geriatric medicine. I noticed all kinds of things that needed to be improved, and I’d come to the management with my suggestions. The field piqued my interest, and that’s how I got my training in the nursing home business.”

He believes that his dedication to his Zeide Fried was a tremendous zechus for him. In 2011, Landau and some partners established The Allure Group, of which he serves as CEO. The company purchases nursing homes that are in danger of closure due to poor maintenance, renovates them, and brings them up to medical and governmental standards.

In 2018, Landau gave $1,300 in bonuses to more than 250 employees in one of his nursing homes, the Harlem Center, for their work in transforming a facility rife with violations and problems to a five-star nursing home. Later, he became a partner in an investment firm that merged with Genesis Healthcare, one of the largest nursing home operators in America, with 250 active homes around the country.

At the same time, Landau converted some of the dysfunctional nursing homes into residential apartments, which gained him entry to the real estate world. In 2015, he purchased a four-story nursing facility for $15.6 million. Then he demolished it and built a luxury high-rise on the site. Then he purchased Rivington House, a troubled nursing home on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, for $28 million. Rezoning it at a cost of $16 million, so that he could build residential towers there, he sold the property at a profit of $72 million.

Today, Landau owns hundreds of nursing homes all over the US. Each one is managed locally, and all profits are then channeled into the national headquarters of the company in Manhattan. He is currently expanding his business to Europe, and as a result, he’s been traveling the New York-London route very frequently.

Where Sanz Meets Jerusalem

If you’d like to get an idea of what ahavas Torah and ahavas beis Hashem looks like, visit 89 Throop Avenue in Williamsburg. There, on the corner of Bartlett Street, is a building that lends prestige to the term Beis Hashem. Gracing the top of the building are illuminated gold letters declaring “Beis Mikdash Me’at.” That’s it. Not the name of the beis medrash, and certainly not the name of the donor.

The grandeur is evident even before you step into the brightly illuminated structure. The architecture is visible from a distance, with balconies running along the front, soaring pillars at neat intervals, and a unique façade: There’s not a typical New York red brick in sight. The entire building is covered in artfully laid Jerusalem stone.

The stone was actually brought over on a very expensive shipment of a fleet of ships at a cost of four million dollars. The factory that produced this stone is the same one that manufactured the stones for the large Gerrer Beis Medrash in Jerusalem. The cement, incidentally, was brought from Israel as well. Later, special builders were brought from Israel, because American construction workers don’t typically have training in laying Jerusalem stone.

The building is five stories high, with four entrances and a spacious lobby graced by a magnificent light fixture in the style of Jerusalem’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, and an impressive wall of Jerusalem stone, etched with the words of Chazal that are the basis for the concept of this shul: “Asidin batei knessios, the shuls and batei medrash are destined to all be established in Eretz Yisrael.”

The expansive beis medrash is a truly elevated place to learn, with marble walls, a breathtakingly beautiful aron kodesh, and galleries overhead with benches and tables. The bookcases are stocked with hundreds of siddurim and Tehillim and Chumashim — all with expensive leather bindings, each worth about 200 dollars.

“Here you’ve gone too far,” I tell Yoeli. “Who needs this expense?”

In response, he quotes from Sefer Chassidim (275): “Someone who honors Hashem will also honor the cheftzei Shamayim. If you have silver and gold and you put them in an elegant box, then how much more so you should do the same to the sifrei kodesh and put them in an elegant box or cabinet…. Because in every place, we find the aron plated with gold, to teach us that everything that revolves around a mitzvah needs to be with kavod and beauty.”

In this beis medrash the hum of learning resounds around the clock: It starts with a kollel chatzos, and then a predawn kollel, followed by a kollel for balabatim who learn for three hours before going to work, and then a kollel for dayanus, where eminent talmidei chachamim sit until the evening — at which time the yungeleit from the kollel erev will come, followed by the kollel chatzos. And then it all starts again. So the lights never go off here in the Beis Medrash Ohr Chaim Ribnitz.

I will later learn that 24 members of the dayanus kollel live directly above the beis medrash, in fully appointed, rent-free apartments that allow them to avoid financial worries and invest in Torah learning day and night.

Behind the beis medrash is the otzar haseforim, one of the largest Torah libraries open to the public in the world, with more than 22,000 titles. In the middle of the otzar is a huge table, with large deerskin chairs, for the comfort of the lomdim.

Of course, there’s a free supply of coffee and chocolate milk, and that’s even before we go downstairs to where the shtiblach and mikveh are housed. There are four beautiful shtiblach, each named after a different tzaddik: the Berditchev Shtibel, the Lizhensk Shtibel, the Sanzer Shtibel, and the Radomsker Shtibel.

While in all the shtiblach in the world, the gabbaim announce “Minchah in Shtibel Alef” or “in Shtibel Beis” — here the announcement is different: “Minchah in Sanz,” “Minchah in Lizhensk,” and so forth. The aron kodesh in each shtibel is designed in the style of the matzeivos of the four tzaddikim: Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, Rav Elimelech of Lizhensk, Rav Chaim of Sanz, and Rav Shlomo HaKohein of Radomsk, and quotes from each regarding the importance of tefillah are incorporated into the design.

I meet Yoeli at five in the morning in the Lizhensk Shtibel. America is still sleeping, but Yoeli is already here, after his first chavrusa of the day, a Belzer chassid from Eretz Yisrael who uses the late morning hours in Eretz Yisrael to learn with him over the phone.

Yoeli comes here without his phones, completely disconnected from the world of commerce, and davens with a geshmak that should arouse everyone’s envy. His money, he surmises, is probably a result of his tefillah — he’s been davening vasikin for 20 years, and he sees it as one of the secrets of his success.

The neitz minyan in the Lizhensk Shtibel is slow and deliberate. New York and its wealth of opportunity will have to wait patiently; the people here are focused on the true Treasurer. Even after they finish, they don’t take off their tefillin right away. Instead, they recite Tehillim together, then they say the yehi ratzon and the Yud Gimmel Middos. Only then does davening come to an end.

Nu, now we can finally eat something and set out for Manhattan, I assume. Turns out, I assumed wrongly. Yoeli goes up to the grand beis medrash and sits down with his morning chavrusa, Rabbi Lipa Friedman (the son of Reb Moshe Menahel, as he is known, the legendary director of Satmar Institutions), and they learn for the next two hours. They learn sugyos: They start with Shas, then Rambam, and then Tur and Shulchan Aruch, and Shulchan Aruch Harav and Mishnah Berurah.

Only after this learning session concludes — close to noon — do we set out for the Big Apple.

Beeber Hit in the Big Apple

Yoeli Landau runs his business empire in a gleaming skyscraper known as the Lipstick Building on Third Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, between 53rd and 54th Streets. The company is housed on the 28th and 29th floors of the building, with a parent company called Pinta Capital Partners and numerous subsidiaries that own about 1,000 nursing homes, hundreds of pharmacies, and an array of other holdings in the health industry across the United States. The company privately invests in health initiatives and signs new contracts on almost a weekly basis.

Walking into the office makes me a bit dizzy. There are dozens of workers here: a small number of chassidim, a larger number of Litvish and Modern Orthodox Jews, and yet others who are not observant, or even Jewish. To my surprise, Yoeli Landau walks around here like just another worker — no conceit, no air of authority. He speaks to people casually, offering jokes between business talk.

A meeting of the board is convening. Several lawyers and accountants, Jewish and not, gather around the table as they get ready to listen to the boss — the yungerman with the curly peyos, the woolen tallis katan, the long chassidic suit and the big yarmulke, who never even stepped into a college or business school.

But if there’s something that Yoeli is proud of it’s this fact: “I never learned English — I got married with a poorer English than an Israeli yungerman,” he says. “And I certainly didn’t study any financial profession, no business administration, nothing. I attended cheder and yeshivah, and then I went out into life, and Hashem took care of everything I needed.

“But even more important than that,” Landau says, “is the fact that it never entered my mind to ‘gentrify’ my appearance. In the previous generation, I saw all kinds of frum businessmen who, when they came to Manhattan, tried to hide their chassidish appearance. They tucked away their peyos, switched to modern suits — all to look the part of the successful businessman. But I never changed my long coat or put my peyos behind my ears. I go with my peyos arup gelozt (down loose). I come to work with my hat and suit and my chassidishe tallis katan, and I try at every minute not to forget where I belong and Who I am serving.

“This is the vision of our Rebbe, Rav Yoel of Satmar. When he arrived in America, he refused to compromise on a single detail of the chassidish mesorah. His detractors told him, ‘In the end America will defeat you.’ And he replied, ‘When you’ll see yungeleit going out to 47th Street in Manhattan with woolen tzitzis, you’ll know that I defeated America.’ I am happy to be the smallest of these people announcing his victory.”

I’m still walking with Yoeli through the offices as he interacts with his employees — here a pat on the back, here some sincere interest, a warm conversation — when I smell something strong. Yoeli notices my surprise and leads me to one of the rooms in the office complex: the kitchen. An expert chef is standing there, cooking portions of meat for the employees who will soon be taking their lunch break. Behind the chef stands a mashgiach, a Belzer chassid who comes every day from Boro Park and brings along Satmar-certified meat.

The aromatic dishes cooking now are just the tip of the iceberg. There are seven kitchenettes spread over the two floors. Each has a refrigerator stocked with ready food — from sushi to sandwiches, all kinds of snacks, chocolates, and a huge variety of beverages. There’s even a station for alcoholic beverages, alongside a special machine designed to pour wine without the need for a human hand, to prevent problems of yayin nesech.

Yoeli explains that this is part of his vision. “When people work in comfort, their productivity is much better.”

In recent years, Landau has avoided commercial flights, even in business class. He travels in a private jet. Crazy? Wasteful? According to Landau, it’s a matter of principle. Three principles, in fact.

“First of all,” he explains, “I really think that Hashem created shefa so that Yidden should enjoy abundance. If Hashem blessed someone with wealth, and his personal conduct does not come on account of his generosity to tzedakah, then why should he refrain from having a private jet?

“But there’s something deeper here. I think that when someone is generous toward himself, he can then be generous to others. I know enough gvirim who live frugally. They think and rethink every expense, pinching and scrimping wherever possible. You can imagine what their tzedakah is like.

“And I have a third consideration — the spiritual component. With the private jet, I’m not dependent on airline schedules, and this way I can plan my trips in a way that I will never miss out on davening with a minyan. For me, that’s a very firm principle. It’s one of the secrets without which it’s not possible to have birchas Shamayim. Plus, it spares me from walking around in airports, which present serious challenges in shemiras einayim.”

He then adds, “I believe in the approach of mochin d’gadlus, a kabbalistic idea that there are two types of mind-frames — narrow and expansive. I believe that Hashem sends brachah according to the keilim, the vessels that the person prepares — a big, generous vessel will hold a lot more brachah. Since the day I cut myself free from those welfare payments, I aim for the expansive mindset, the mochin d’gadlus, in everything I do.”

Give and Get

Suddenly there’s a surprise guest. The mayor of New York, Eric Adams, appears at the entrance of the office. Yoeli is hardly moved by the visit — he doesn’t even stand up. He politely welcomes the highly guarded mayor. It’s clear that Yoeli is used to these visits. Adams has a few important things he wants to discuss — chief among them, soliciting support for his run for reelection this November. Landau is a key figure in the map of Jewish support, and Adams has come to ask for his active — and financial — support.

I use the opportunity for a quick chat with the mayor, and I compliment him for his strong support for Israel after the October 7 attacks. Adams seems pleased, and uses the opportunity to relay his own message: “Everyone needs to be afraid of a Mamdani victory,” he tells Mishpacha. “I’m the best one for the Jews, and I will continue to be. I get a lot of inspiration from the leaders of the Jewish people.”

At exactly 2:00, the activity in the office stops. The Jewish workers come out of their rooms and desks and gather in the middle for Minchah. After Minchah, there’s a short practical shiur on the halachos of ribbis given by a talmid chacham who visits the office each day for this purpose. The Jewish employees discuss a deal that’s on the table, and they examine the various halachic aspects of it.

After the shiur we sit down in the office of Eli (Elliot) Schwab, president of subsidiary Apex Healthcare Properties. A grandson of Rav Shimon Schwab ztz”l, he sees eye to eye with Yoeli about the spiritual principles that are the basis for success. Our conversation is joined by Yechiel Lerfield, an alumnus of Lakewood, and Yoeli uses the chance to conduct a conversation in English about the obligation to distribute as much money as possible to tzedakah.

“How much do you think a wealthy person must give to tzedakah?” I ask.

“More than fifty percent,” he says simply.

“More than fifty percent? What about takanas Usha? There’s a clear Gemara saying one should not give away more than a fifth of his holdings,” I challenge him.

Yoeli’s response stuns. “I’ll tell you the truth. For every statement of Chazal in Shas, I can open seforim and try to find an explanation. But this one has no explanation. I just can’t understand it! I see clearly how every million dollars that I give for tzedakah, is immediately returned to me, many times over. So why not give more than a fifth?! In my experience, the more you give, the wealthier Hashem will make you.”

“And you don’t feel any angst when you give away millions of dollars?” I wonder.

“Angst? I feel angst when I don’t give the money!”

That said, Yoeli is still careful to adhere to the recommendation of Chazal, and he utilizes various maneuvers so as not to explicitly transgress the takanah of Usha: First, he takes off a fifth of his general income before the tax is taken off, and then more ma’aser, and then again, until he reaches 50 percent of the company’s gross earnings.

Yechiel Lerfield, an accountant, opens his computer and shows me how the company records each deduction for charity. And yes, the total amounts to more than 50 percent.

Stop Being Schnorrers

Now our interview moves onto one of the burning issues of the day, a subject that Landau is passionate about: His suggestion to extricate Eretz Yisrael’s chareidi population from the pit it finds itself in vis-à-vis the State, which has earned him both accolades and criticism.

“I want you to know,” I tell him, “that the chareidi public in Eretz Yisrael has a simple question: Who asked you? We follow an approach set by gedolim. Why should an America gvir — as big of a Torah supporter as he might be — come and give us advice?”

“You’re asking a good question,” he says warmly, “and it’s good that you asked. So first of all, I’ll tell you the whole truth: I didn’t get into this of my own accord. Last winter, a group of roshei yeshivah from Eretz Yisrael met with me, and asked me to get involved, because the conflict with the State was growing more acute.

“At first, I refused. I said that I didn’t want to get involved at all. We have such different worldviews, it would just be a waste of time. But there were more appeals from other directions. They wanted not just financial support, but also advice. And I began to think that maybe Hashem was guiding me to this position, and I could avoid getting involved for only so long.”

Landau had long thought that the chareidi community should relate to the State with a cold, hard financial approach. No more pleading, no more pressures and political machinations. And no emotional, “nebach-inducing” mentality either. No angry or accusing headlines in the newspapers. Just a businesslike attitude.

To put it succinctly: “Stop being schnorrers.”

This summer, he had a chance to share that approach with the most politically influential chassidic court in Eretz Yisrael. Gur is the central chassidic group in the historical Agudas Yisrael movement. In Gur’s view, Agudas Yisrael is not only practical, it’s ideology. The Imrei Emes zy”a established the movement. His sons and successors, the Rebbes that followed, strengthened it. His grandson, ybl”c, the Rebbe, is the Nasi of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudas Yisrael, which is an integral element in Gur.

The Agudah shitah promotes participating in the Israeli elections. It supports sending chareidi representatives to the Knesset, and seeks to cooperate on a practical level with the government establishment. The most recent representative, Yitzchak Goldknopf, is just the latest in a line that traces back to the very first representative, Rav Itche Meir Levin ztz”l.

Satmar is situated on the other extreme of the ideological spectrum, opposed to the Zionist State and any form of cooperation with it. In light of the deep ideological gaps, a meeting between the worlds of Gur and Satmar — to address practical matters, not for a ceremonial l’chayim — would seem like wishful thinking, at best.

But the chareidi community was pressed to a wall. That is how Yoeli Landau found himself inside the Rebbe’s inner chamber, sharing his Satmar and business-shaped views on the burning issue of the day.

“I’m suggesting something simple: Stop being k’chagavim b’eineinu, like grasshoppers in our own eyes. Stop seeing yourself as weak and needy. Remember Yoeli the poor yungerman from Williamsburg, who signed up for every government handout possible and lived in poverty — until one fine day, he decided to cut himself free and stand on his own two feet. I wanted to utilize the siyata d’Shmaya that HaKadosh Baruch Hu sent me after this decision, to share it with the public, and even with individuals who will read this over Yom Tov.

“People think the ideology of the Satmar Rebbe is only against taking ‘impure money.’ Of course that is true. The Rebbe explains this principle in his seforim. But I am not a rav or mashpia. My role as a balabos who is a Satmar chassid is to translate the Rebbe’s shitah into the language of success in a practical way.”

He presents what he views as the crucial metaphor: “The Satmar Rebbe said something simple: As long as you depend on others, you leave yourself no room to grow. As long as you maintain that glass ceiling, you have no space in which to flourish. You’re limited to those handouts, and you have to constantly say thank you no matter how meager they are, and worst of all — you are always dependent on what others think. They will decide when to give you money and when to shut the spigot, they will also dictate what you will learn and how you will conduct yourself. Is it any wonder that we got to this major draft crisis?”

By Your Bootstraps

Landau’s philosophy relies on what he calls “koach la’asos chayil” — a Jewish version of the American “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” approach to business success. “You have to realize that it all depends on you, on your shoulders, on your courage. There is nothing outside you that can block you from reaching your goals. Every person has every opportunity to reach his aspirations and realize them.”

This is a worldview where success is measured not by academic degrees or formal years of education, but by initiative, smart thinking, and a willingness to take calculated risks.

“In contrast to the complex bureaucratic systems in Israel, in the American business world no one asks me which university I attended or which academic degree I have. Academic credentials don’t interest anyone. In the commercial sector, some even disdain them.

“The questions I get are different: What do you know how to do, how do you think, and what are your results. That’s an approach that provides an equal opportunity for each person — whether he comes from a rich family or he’s a penniless yungerman who slept in batei medrash and decided one day to join the business world. This system gives each person the opportunity to succeed.”

Landau himself actualizes this philosophy: At his weekly board meetings, educated lawyers and professionals with years of study and training under their belts find seats around the mahogany table. And they all lean forward to hear the chassid with the long coat and curly peyos giving instructions in basic English.

“I see it as a kiddush Hashem,” he says. “Sometimes, business partners, most of them not Jewish, ask me: ‘How did you get to where you are?’ And I point upward to the Heavens and I say: I have a method of three words in Lashon Kodesh: Koach la’asos chayil, or in English, the power to prosper. This power is a Divine property that is bestowed from Above to anyone who believes in the power of Hashem, and then has the courage to make his own human effort.

“Tefillos are the gate to success — along with emunah in the kochos the Creator gave you to succeed is the success itself,” he says. “I believe that as long as you wait for someone to help you, you remain stuck in one place. It works in business and it works in life. The question is if you believe in your abilities.”

Negotiating Tactics

Yoeli brought that business mindset into the Gerrer Rebbe’s room. “I think he appreciated what I was saying. I said, ‘In the business world, it all depends on the opening offer — if your opening bid is good then you have a chance, and if it’s not, the deal is off the table.’

“The way I see it, the chareidim presented such a weak opening bid on the draft issue that they had no chance of emerging with anything remotely acceptable. If we’d declared right at the outset that we’re sticking to our principles and refusing to play the game, then things would look very different.

“I told the Gerrer Rebbe that I was once present for negotiations on a huge deal of $3.5 billion. At a certain point in the negotiations, the other side began to discuss terms very different from what we’d discussed at the earlier-stage talks. I didn’t even bother discussing their new terms — I just stood up and left. Everyone was in shock, but of course in the end, they backed down. I told the Rebbe — of course, after getting his permission to state my view — that the concept of negotiations in itself projects weakness. Only when they realize that they will not accept any compromises will we succeed.”

It’s one thing to share views privately, but that’s not where it ended. After the Gerrer Rebbe completed his emergency fundraising trip, Yoeli Landau availed him of his private jet for the return flight. During the flight, he handed the Rebbe a long and detailed letter exhorting the Rebbe to take the lead in steering Israel’s chareidi population in this new direction.

The letter went public, and sparked heated conversation and debate. Many accused Yoeli of brazen chutzpah for implying that he had read the map more accurately than the esteemed Rebbe of Israel’s largest and most powerful chassidus.

But it wasn’t like that at all, he explains. “After the meeting in the Rebbe’s house, where I was explicitly asked for my opinion, I felt like I had not made myself clear enough. Every moment in his presence was very measured — you know the Kotzker mehalech of extreme conciseness and brevity. I was in such awe when I was there that I wasn’t sure I had expressed myself well enough, or fully enough. So I thought, in light of the Rebbe’s request to hear my opinion, I had the responsibility to express it in more detail. That’s why I wrote the letter.”

But why did he publicize it in all the chareidi news outlets? What was he hoping to achieve?

“Chas v’shalom I should publicize such a letter!” Yoeli exclaims. “I have tremendous reverence for and deference to the Gerrer Rebbe, especially as a chassid of Satmar, which over the years has had warm ties with the Rebbes of Gur. Whenever our previous Rebbe, the Beirach Moshe ztz”l, visited Eretz Yisrael, he visited the Gerrer Rebbes, including the current Rebbe shlita. It didn’t enter my mind to publicize such a private letter, and I’m very upset that it was leaked.

“I can tell you,” he adds, “that I still have a good relationship with the Rebbe’s household, and I’m hoping to work on other initiatives in the future for the benefit of chareidi Jewry, if there is a desire on their part for me to contribute. I’m not telling anyone what to do and how to act. The letter was my personal plea, based on my background and experience. But I’m not one to impose my views on others, certainly not on the leaders of Klal Yisrael.”

Going It Alone

But Yoeli finds it hard to keep his equilibrium as he describes just how badly the situation has deteriorated. “I’ll show you how it plays out,” he says with passion. “The media and politicians in Israel have managed to label the chareidi public as parasites who don’t contribute to the country, and we somehow go along with that. That in itself is a success for them. Now, when you get to negotiations with a humble air — as a ‘non-contributor’ — you’re mentally prepared to accept any compromise.”

“As a businessman who knows something about numbers,” I ask him, “how would you counter the claim that chareidim don’t contribute?”

“I say it is absolute nonsense. The people who make this claim probably visualize some stereotypical kollel yungerman from Bnei Brak, but let’s look at the macro. The chareidi sector in Israel is one of the country’s biggest growth engines. Let’s break it down for a minute: Do you know how many hundreds of millions of dollars the chareidi Torah institutions contribute to the State’s coffers each year?

“I’m familiar with the numbers. They are astronomical sums that help turn the wheels of the Israeli economy. Anyone who doesn’t recognize this huge contribution is a rasha and a kafui tov. They have managed to persuade you — the chareidim in Eretz Yisrael — that you ‘don’t contribute’ and somehow you just go along with it.

“There are lots of areas where the chareidi public as a collective makes exceptional contributions to the economy — from Jewish tourism for the Yamim Tovim and through the entire year, and the many chesed organizations — Ezer Mizion, Yad Sarah, and all the rest, who help all citizens and remove a huge financial burden from the State.

“Who decided that the only way to contribute to a country is through direct tax payments? And by the way, there’s plenty of tax money coming out of the chareidi public, too. There’s a wealthy sector there, and many businesses and industries, too. It’s high time we stopped subscribing to this distorted narrative of a public that ‘doesn’t contribute.’

“In short, I think you get the gist. You have to reset the negotiations. Start talking about who contributes and how much — but don’t negotiate under fire.”

“It sounds very nice in theory,” I say. “But practically speaking, do you know how much money chareidim receive from the government? The Gerrer institutions, for example, receive half a billion shekels. Do you really think they’ll be able to keep functioning without government funding?”

Yoeli replies with a big smile: “It’s a good thing you weren’t present when the Satmar Rebbe decided not to take money from the State. And who knows, with your thinking you might have dissuaded America’s roshei yeshivah from building their entire empire — which subsists on its own funding. It’s also a miracle that my wife didn’t hear you when I decided to wean myself off welfare, because then you would be meeting today with the schnorrer Yoeli Landau — and honestly, you wouldn’t have even wanted to meet me.”

Then he turns serious. “I think that yes, Gerrer chassidus can definitely support itself, and the same is true for every community in Eretz Yisrael. Even if not right away, the potential certainly exists. If the gvirim in Gur push themselves beyond what they think is possible, and the balabatim decide that they’re becoming gvirim in order to support the mosdos, and there forms this internal competition among the affluent to be the most generous giver — then the whole culture will change, and not only in Gur. I have full faith that the more independent the Torah institutions in Eretz Yisrael will become, the more they will grow and achieve.

“The Satmar Rebbe told his people: ‘If you start giving lots of money to tzedakah, then you’ll need more money. And then you’ll work harder, you’ll invest more, and you’ll have more money, and then you’ll give more. And then you’ll need more, and you’ll earn more and you’ll give more.’

“I see how true that is in my own life. As far as I’m concerned, every deal I make is so that I should have the ability to give tzedakah. It’s the recipe for financial success.”

“Okay, let’s move on from Gur and talk about the other Torah institutions in Eretz Yisrael,” I suggest. “There are hundreds of mosdos — Litvish, Sephardic, and chassidic. The state budget for Torah institutions is about NIS 8 billion a year. Do you think they can all manage without state funding? You saw how the leading roshei yeshivah of Eretz Yisrael struggled to raise money on their recent fundraising trips.”

“I’ll ask you the opposite,” Yoeli counters. “In the last seventy-eight years, has a gadol ever completed a fundraising trip with one thousandth of such a sum? On the first trip after the government held back funding, the Keren Olam HaTorah raised one hundred million dollars. It’s a fantastical sum compared to the past. Do you realize what happened? They just established the infrastructure. Now that it exists, it can be expanded, from outside and from within. It shows that there is a genuine desire and emunah, that things are happening. The problem is not the ability — the problem is the mentality.

“As long as we see ourselves as needy, we will never thrive,” Landau repeats. “Remember my story. Remember the yungerman from the bench in the beis medrash in Williamsburg who realized one day, ‘As long as I rely on government handouts, I won’t succeed in life.’”

The man who began his life with 1,000 dollars in a damp basement in Williamsburg and reached the pinnacle of his industry is offering a simple and revolutionary message: Stop waiting for someone to help you. The first step to success is to stop relying on others and begin to trust the One who gives you the power to succeed. It all begins with taking that leap of faith, Yoeli says, and the siyata d’Shmaya will follow.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1081)

Oops! We could not locate your form.