Death by WhatsApp

Can we stem our urge to spread tragic news?

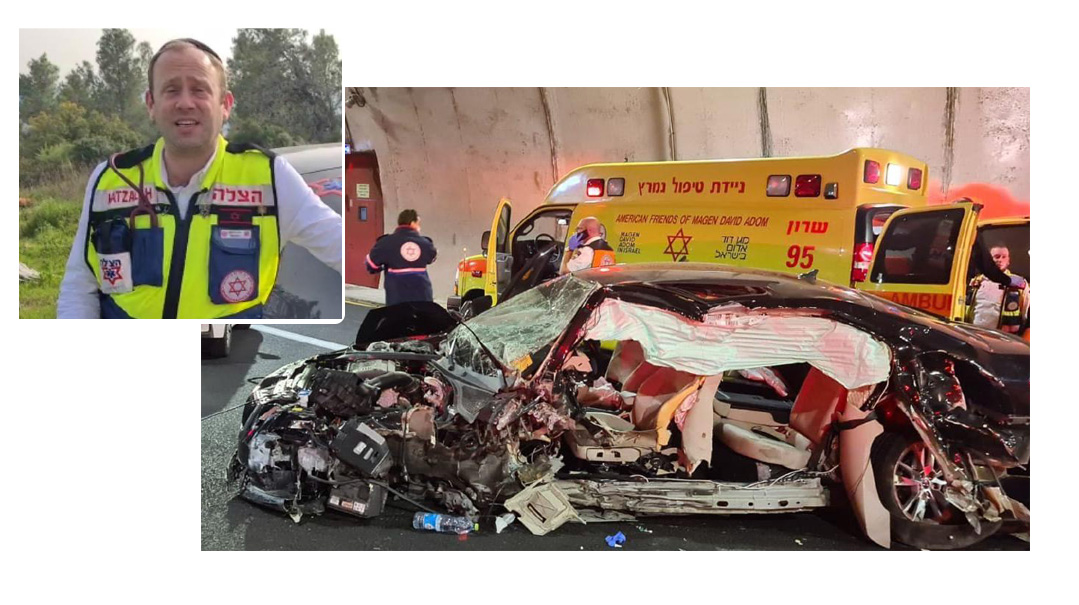

Photos: MDA, Family archives

“Why are you publicizing this? I’m his wife and no one told me yet!”

These words were typed this Chol Hamoed Pesach, moments after a horrific car accident in which Reb Chaim Har-Kessef of Bnei Brak was killed. They were typed by a woman during the most desperate moments of her life. They were typed in blood, and time will tell whether they can effect any change in a communal trend of instantly posting, sharing, and spreading news that can wreak terrible damage.

“I was there when the accident happened,” Mrs. Revital Har-Kessef tells Mishpacha. The family had taken two cars, and Revital, her son and daughter-in-law were in the other car, when she saw her husband — a beloved Hatzolah volunteer and baal chesed — lose control of the wheel and slam into a stone wall in a tunnel near Yokneam. Everything stopped. Her older son jumped out and began CPR on his father, while they waited for rescue forces to arrive. The professionals took over, and she recited Tehillim in icy fear. Then her phone pinged. Someone had apparently deemed it very important to report that Chaim Har-Kessef had been killed in the accident.

“I saw what was going on and I heard the terms the EMTs were using. Because Chaim himself was a volunteer in rescue organizations for many years, I understood what it meant. Still, I continued saying Tehillim — I’m a believing Jews and I know that there is always hope. But then someone posted a message clearly stating that he was dead. I have no idea how a person is capable of posting such information during such a fragile, sensitive time.”

She pauses and clarifies: “I know that this trend exists. I’ve heard of cases where people discovered the loss of their loved ones through such posts. I found it horrific. But then it happened to me and I felt the pain firsthand. And it wasn’t just me — my oldest son, who hadn’t come along on the trip, was heading for the hospital. I told him the situation was critical, but I was so afraid he’d learn the truth the same way — which is what ended up happening.

“That’s why I decided — maybe if I speak out openly and honestly, people will take it to heart.”

Revital doesn’t think anyone leaked the news maliciously. “I don’t think it comes from a bad place — people are curious and have this hunger for fresh news. You know, when someone speaks lashon hara, they’re usually not acting out of malice either — but that doesn’t mean it’s not a terrible thing to do.”

For Revital, that update was just the first chapter in a continuing saga.

The fresh widow spent the next night right near the hospital. She couldn’t fall asleep as she fearfully awaited the surgery soon to be performed on her daughter Naama, who’d been seriously injured in the accident. And then she saw another WhatsApp message. “Someone posted that my daughter’s condition was deteriorating and that she was fighting for her life.”

She takes a deep breath, and suppresses a sigh. “From that moment on, the phone didn’t stop ringing. Everyone was desperate for an update. If they couldn’t get through to me, they tried my son. I needed those few hours of quiet after the most draining day of my life — I’d even taken a sleeping pill — but I couldn’t fall asleep. I kept thinking about people sitting over their keyboards and simply committing murder. I have no other words to describe it.

“It’s not easy for me to talk about this but I’m doing it because people have to realize how destructive they’re being. You have to stop spreading these messages, stop posting your ‘scoops’ and putting pressure on people going through the most terrible circumstances.”

United Hatzolah founder Eli Beer was one of the first responders to the Har-Kessef accident. “I happened to be on a Chol Hamoed trip in the area, so I was able to be on the scene within seconds. My wife administered CPR to 17-year-old Naama, who was badly injured, and my son-in-law and I tried to save Chaim.

“The accident took place far away from any residential areas, so it took the ambulances 25 minutes to arrive. The awful thing was that as I was working on Chaim, his wife standing nearby got a text saying ‘Baruch Dayan Ha’emes.’ It was terrible. As far as we were concerned, he was still alive and breathing — I was right there and I knew the situation. How can someone sitting in his living room in some faraway city decide matters of life and death with a swipe and a click?”

Eli has garnered enough unfortunate experience over the years to know that there’s a certain personality type usually involved.

“There are people who, regretfully, have this terrible urge to be ‘in the know.’ With today’s technology, it manifests in this need to be the first to post anything, before anyone else,” he says.

“But we have to fight this urge.” Do the people who post such messages ever think what would happen if he or someone close to him were the subject of the message? No one is immune to tragedy. Before someone presses ‘send’ on a ‘Baruch Dayan Ha’emes’ message, he should think twice.

“Think of the family and imagine them learning the news through that message you sent. A family that experiences such a tragedy deserves to be informed in a controlled way — sometimes by professionals, sometimes even with medical support. There are people who might be harmed for life if they receive tragic news in a shocking way.

“In the case of the Har-Kessef family, after we finished treating Chaim a”h, we still didn’t know exactly what his condition was, because he’d been taken to the hospital. But Chaim’s brother came to the scene to take the children. I asked him to turn off his phone until the end of the ride so that they shouldn’t get a message in a way that might harm them.”

But these messages tend to spread like wildfire. “I encounter this situation all the time,” Beer adds. “And each time, my heart breaks. Too many people consider themselves ‘amateur journalists’ or ‘news sources’ — and by the way, I’ve found that the official journalists are usually more responsible and do not publicize things without explicit permission and verification. It is the amateur and unappointed news peddlers, on the other hand, who seem to get some sort of high by posting messages that make waves.”

Eli shares a painful personal memory.

“Last year, I was critically ill with COVID. I had to be intubated and sedated. While I was hovering between heaven and earth and battling for my life, my married daughter got a message from a friend: ‘I was so sorry to hear about your father.’ When my astonished daughter asked where she had heard that from, the friend showed her a ‘Baruch Dayan Ha’Emes’ message that she’d gotten.

“I didn’t hear the story until I was recovering, but it was still a terrible feeling. I couldn’t fathom how someone had the chutzpah to decide that I was dead, while the doctors were fighting for my life. It was a good thing that my 91-year-old mother hadn’t gotten wind of the message, because who knows if she would have been able to withstand such terrible news shared in such a casual way.”

Military historian Dr. Yagel Henkin, the brother of Rabbi Eitam Henkin Hy”d, who was murdered with his wife in a terror attack on Succos in 2015, relates that to this day he hasn’t received official notice of the murder of his brother and sister-in-law. “In my case, I was at an event and I heard that there had been an attack. It didn’t enter my mind that it was connected to me. Toward the end of the event, my mother called me and said she couldn’t reach my brother. I began to look into it, and then received a message from a close friend: ‘Dear Yagel, I was so sorry to hear. With you in your grief.’ Only then did I realize what had happened.

“Later, it became clear to me that he had sent me the message because the names of my brother and sister-in-law — and even their pictures — had already been publicized. That was before we, the close family, were updated. To this day, I don’t know who was the first to release the names.”

As a public figure, Dr. Henkin has been approached by many others who’ve experienced the same jarring phenomenon. “Lots of people who went through similar stories reached out to me and told me about the pain and trauma that they carry to this day because of the way they learned of the death of a loved one. I have no reason to think any of this will stop, because in the State of Israel, there is no law relating to the way we update families. The only law that exists relates to soldiers, where there is a gag order on media exposure of victim’s personal details until the families are informed through official channels.”

Even if a similar law were enacted regarding private citizens, Dr. Henkin is doubtful how much of a dent it will make. “I imagine that such a law would help with regard to the official media, but it won’t help with private messages, because there will always be people who will hear about it and will spread these details. Ultimately, no official regulation will be able to replace common sense and fairness.”

“When my parents were killed in a car accident, it was excruciating,” says Yehuda Nezri of Migdal Ha’emek. “But the way I found out — with no prior warning, through a social media post — made it even harder.”

His memories of that day keep flashing back: “It was last Chanukah. I work as a security officer in a school in the Gilboa region, so I was on vacation and my children were at home. Suddenly I got a message about an accident on Highway 90, near the Dead Sea. For some reason I decided to open the message, and then I saw a photo of my parents’ car at the scene of the accident.

“I immediately identified the car. I also knew my parents were supposed to be on that road then. Still, I kept telling myself they were okay somehow…. An hour and a half later, I heard knocking at the door, and when I saw a police officer and a member of the welfare department, I told them, ‘I know what happened already, you don’t have to tell me.’ ”

He still wonders about the people who felt the urge to post a photo of the car at the scene of the crash. What motivates people to document and spread graphic images of tragedy? “They didn’t even try to blur the license plate, which is a minimal effort,” he says. “Later, I found out something even worse: After the accident, another video was posted, showing a doctor trying to resuscitate my mother, and another clip in which my father’s body was visible. I thank Hashem for sparing me from viewing these horrific clips, but I don’t understand how people have the audacity to post them. It’s a total bizui hameis, a disgrace of the dead.”

Nezri doesn’t think too highly of those with itchy fingers: “Before you share information, try to think what would happen if you were in that family’s place. How you would feel if you would get such news in such a casual way? I don’t wish for anyone to be in this place, but when it’s such a horrific tragedy, professionals need to be involved in sharing the information with family.“People are looking for their five minutes of fame, for likes, for attention and acknowledgment. There’s no greater thrill than documenting something strange, scary, or unusual. What they don’t realize is that in their drive for that feedback, they’re hurting people in the most vulnerable moments of their lives. Is any attention worth that price?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 858)

Oops! We could not locate your form.