Darkness in the City of Light

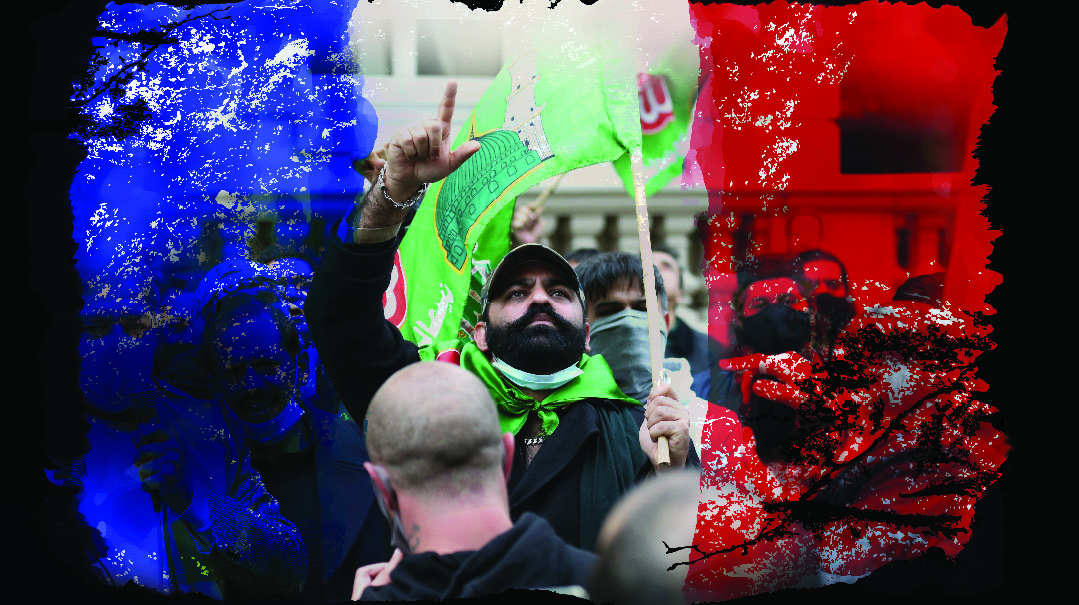

| June 8, 2021On-site report from the Paris neighborhood where Sarah Halimi was killed by an Islamist radical

Yisrael Yoskovitch, Paris

It’s Eid al-Fitr, the Muslim holiday marking the end of Ramadan, and young men dressed in gallabiyahs and flowing beards crowd the sidewalks as I’m driven along the Boulevard Périphérique, which divides Paris proper from the heavily immigrant suburban banlieues.

As an Israeli, I feel strange having to wear a mask again — back home, they’ve been out of fashion for a while now. A safety screen separates me from the dark-skinned taxi driver. Parisians don’t take chances when it comes to Covid. He whistles snatches of a wistful chanson, and periodically glances in the rearview mirror to check on his Middle Eastern tourist. There are no smiles.

As we enter the Belleville neighborhood, I’m getting reports about the latest outbreak of hostilities as Hamas and Israel trade blows. But forget distant Gaza — I’m here because of the violence on these very streets. It’s just four years since the horrific murder of Sarah Halimi, a religious Jewish doctor, put Islamic terror and this volatile neighborhood on the map. In Belleville to take up the story that Sarah Halimi’s son Yonatan told in these pages a few weeks ago, I’ve been warned to conceal my Jewish identity. I pull a baseball cap out of my suitcase, don a short windbreaker, and do my best to look inconspicuous.

The driver drops me off on a side street. After a three-minute walk, I reach the address, 30 Vaucouleurs Street. A fire truck is raising its rescue crane to one of the apartments, and a small crowd has gathered outside. I utilize the distraction to slip in unnoticed.

In the lobby, I bump into a resident who demands to know my business. I choose to tell the truth: I’m a Jewish reporter, from Israel, here to see the scene of the crime.

He considers this for a moment before saying, “The appartement is on the third floor. When you’re finished, I’ll be waiting below.”

At the end of the stairway is a worn, brown door draped with red ribbons. A Paris police department notice marks the apartment as a crime scene closed to the public. I retreat. The resident is waiting for me at the entrance of the building. He opens a side door to a small private backyard, and points upward: “That’s the flat.”

“The flat” is the residence of Sarah Halimi Hy”d. Several days before I set out to Paris, France’s top court upheld a ruling that Halimi’s Muslim murderer — her neighbor — could not stand trial because his judgment was “abolished” by drug abuse at the time of the crime. This decision sparked a furor in the French Jewish community and a nationwide series of mass protests.

Now as I stand in the small backyard, the resident points to the spot where Halimi was found. He looks embarrassed and asks not to be photographed.

I try to imagine those horrifying moments. Forty minutes of blood-curdling screams piercing the air. Police officers called to the scene, hearing the woman’s pleas but waiting outside due to regulations forbidding them from entering private homes without a court order between midnight and 6 a.m. When they hear the shouting in Arabic, they realize that’s irrelevant — but then a new problem emerges. In these circumstances, their orders are to await the arrival of elite anti-terror squads trained to handle such situations.

The murderer, Kobili Traoré, uses the interval to viciously beat his Jewish neighbor, all the while yelling “Allahu Akbar” and verses from the Quran. In the end he raises her to the window and throws her to her death in the backyard I’m standing in now.

If Sarah Halimi’s fate left France’s Jews outraged and afraid, four years later, the official response has taken those feelings to a different level. The message whispered at Belleville’s most infamous crime scene, and in conversations with Jewish leaders and activists, is that for France’s political and judicial elites, Jewish blood is cheap.

See No Evil

Standing in front of France’s parliament building is National Assembly Deputy Meyer Habib, one of the first public figures to raise a storm about the Halimi murder, and one of the best-known politicians in the country.

“Halimi’s brother called and asked to speak with me urgently,” Habib recalls. “I didn’t know him, but I took his call as a courtesy. I thought it would take five minutes, and the call lasted an hour and a half. I heard the whole shocking story of his sister’s murder by her neighbor, and the authorities’ refusal to take the investigation seriously.

“From the first moment it was clear to me that the incident was anti-Semitic in nature. Every time he saw her, the murderer would direct anti-Semitic slurs at her. On one occasion he pushed her daughter in the stairwell and used anti-Semitic slurs against her, too.”

The murder occurred at the height of the 2017 French presidential race. Habib hoped to use the momentum generated by the case to call attention to rising anti-Semitism in France. To his disappointment, not one of presidential candidates was willing to pick up the gauntlet. “I spoke with senior parliament members, I held countless meetings on the subject, but no one was willing to address it as an anti-Semitic incident. That should set our alarm bells ringing.”

When asked what the elected officials could have been afraid of, Habib has a ready answer.

“France’s Muslim community numbers 10 million, as opposed to just 600,000 Jews. Nobody here wants to mess with them. When a French policewoman was murdered by a Muslim two weeks ago, all the TV channels covered the story with live broadcasts. But when a Jewish woman was brutally murdered due to anti-Semitic bigotry, no one made a sound.

“Two months after the murder,” Habib continues, “when they saw I wasn’t letting go, a special parliamentary meeting was convened. I yelled to my colleagues: ‘Why do you remain silent? Why do you refuse to talk about the elephant in the room?’ I was sure that after my speech, something would happen. Maybe they hadn’t been aware of the severity of the incident and after I gave them the details, they would be awakened. Sadly, they remained in denial.”

It took the Parisian police three months to arrest the killer.

“It was a mix of anti-Semitism and Israel-hatred, along with reluctance to upset the Muslims,” Habib contends. “We’ve seen some serious incidents over the past few years, and I was sure that this would affect them. Unfortunately, the way of the world hasn’t changed.”

The rise in Muslim anti-Semitic attacks in France started in 2000, with the outbreak of the Second Intifada in Israel. In the two decades since, it has grown into a depressing litany.

In 2003, Sebastien Selam was murdered by a Muslim neighbor in Paris. In 2006, the young Jew Ilan Halimi Hy”d was kidnapped and tortured to death by a Muslim gang; in 2012 an ISIS terrorist attacked the Otzar HaTorah institutions in Toulouse, killing Rav Yonatan Sandler and his two sons Gavriel and Arié, along with Myriam Monsonego, an eight-year-old girl . In 2015, Elsa Cayat, a columnist for the weekly Charlie Hebdo, was murdered along with 11 of her colleagues. Two days later, a terrorist carried out an attack at the Hypercacher kosher supermarket in Paris, killing Yohan Cohen, Philippe Braham, François-Michel Saada, and Yoav Hattab. Then in 2017 Sarah Halimi was murdered in Paris; and in 2018 Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll Hy”d was murdered in her Paris home by a young Muslim.

In a not-insignificant share of the above cases, charges were dropped for various reasons, and in most, the anti-Semitic motive went unmentioned in the indictment. But the Halimi murder was the most blatant case.

“From day one, the investigation was riddled with blunders,” says Meyer Habib. “There was no reenactment of the murder at the crime scene, the killer’s phone wasn’t checked, the family’s lawyers wanted the customary meeting with the examining magistrate, but she refused to meet with them.

“And after all that, when the indictment was filed, the family was shocked to discover that although someone in the prosecution had initially admitted the anti-Semitic motive for the attack, the examining magistrate omitted all mention of it from the indictment.”

In the face of the legal system’s indifference, French president Emmanuel Macron stood at the side of the Jewish community, condemning the silence and calling for the investigation to be followed up. He expressed surprise at the way the police officers on the scene acted as spectators throughout the attack, instead of showing initiative and moving in to prevent a murder. “I fail to understand why the Paris police chief refuses to allow an investigation by the national police force.”

Habib believes that Macron’s words, although important, come too late. “The court’s ruling was dangerous and unethical, and will leave a stain on the French justice system. The law is set to be changed, but it won’t apply retroactively, and sooner or later, Halimi’s killer will go free.”

Double Standards

My meeting with Habib occurred against the backdrop of the Gaza escalation and the civil unrest among Israeli Arabs. It’s clear to both of us that it’s only a matter of time until anti-Semitic elements in the French government — and outside it — exploit the situation to attack the State of Israel.

“My father emigrated to France from Tunisia after a grenade was lobbed into his house,” says Habib. “That’s a crucial element in my family history and identity. My father fled Tunisia because of terror against Jews. When my father arrived in France, there was nothing here. He was the first to produce kosher wine in France and start a mehudar Sephardic hechsher. I tell his story in every meeting with government officials and every media interview. I know very well how the Jews feel in Lod, Ramle, and Yafo, the terror that grips them every time they go to take the garbage out. Sadly, here in Paris we’ve grown used to that feeling. There are places too dangerous for a Jew to venture into.”

Not long after our conversation, French prime minister Jean Castex will deliver a speech in the National Assembly in which he lays the blame for the situation squarely on Israel. “France,” said Castex, “has never stopped emphasizing the dangers entailed by the continuation of the occupation policy.”

In protest at these words, Meyer Habib defiantly walked out. Later, in a phone conversation with Mishpacha, he explains, “It was a speech directed in its entirety against Israel. With great reluctance, he brought himself to utter one sentence of support for the country’s citizens. While he expressed great concern for the people of Gaza, he said nothing about Hamas’s aggression against Israel. Nothing about the hundreds of Israeli casualties, or the millions of citizens (including 120,000 French Israelis) living daily in the reality of sirens and explosions.

“He forgot to mention that the people of Gaza are being held hostage by Hamas. Israel withdrew from the Strip 15 years ago, so there’s no ‘territorial dispute.’ A terrorist group takes two million civilians hostage and robs them of any hope they may have for a peaceful existence, and the French prime minister blames Israel? When France suffered terror attacks, Israel denounced them and stood by the people of France. Cities such as Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Netanya were lit in red, white, and blue as an expression of solidarity with the French people. So I expect a minimum of support and empathy in return.”

Horror in Hypercacher

“You timed your visit well,” Parisian business owner Yossi Cohen ribs me.

We meet next to the Hypercacher supermarket where four people were murdered in a terror attack in 2015. Reports of the violence in Israel intensify. Tension is visible on the faces of local Jews.

“When there’s a security escalation in Israel,” Cohen says, “we’re the first to feel it.”

As we make our way to the storage room in the basement, where Lassana Bathily, a Muslim employee of the store, courageously hid 15 Jews from the terrorist, Cohen receives a report about a number of Jewish youths in the 12th arrondissement being attacked and robbed by knife-wielding Muslims. Cohen hurries over to the scene to get to the bottom of the incident.

I continue to the offices of Oudy Bloch, vice president of the Organisation Juive Européenne, a group that has brought together more than 50 top lawyers working free of charge to combat anti-Semitism in France.

At Bloch’s side sits attorney Gregory Siksik, who represented the family of Yohan Cohen, a victim in the Hypercacher supermarket terror attack; and attorney Jérémie Nataf, a successful Parisian attorney who is painfully familiar with Jewish history in modern France.

“Jews here feel more and more unwanted,” Nataf tells me. “When they fled from pogroms in Eastern Europe, they felt like France could be a home. Now there’s a feeling that France is turning its back on us.”

Despite the fact that most French governments have been staunchly pro-Palestinian, says Nataf, Jews felt safe in the country for decades. Jewish educational institutions, shuls, kollelim, and youth movements sprang up. For France’s Jewish community, spring was seemingly in the air.

Then came the Second Intifada. On Erev Rosh Hashanah 2000, Talal Abu Rahma, a Palestinian cameraman working for a French TV channel, captured footage of 12-year-old Palestinian Muhammad al-Durrah appearing terrified as he took shelter behind his father’s back. Shots were heard, and when the smoke cleared, the boy and his father appeared to have been hit.

The video was played and replayed in the French media and riled up the Muslim community. It would eventually become clear that the video was fake — it didn’t show that al-Durrah had died, and there was no proof that the shots were fired by an Israeli — but it was already too late.

“Jewish life in contemporary France is divided into two periods — before the al-Durrah incident and after,” says Attorney Nataf. “It’s not just the Muslim fury against us — even more important is the public sympathy for the Palestinians. Public opinion was swayed by media incitement. Although we know the IDF is the world’s most moral army, years of nightly TV hit jobs took their toll.”

The Jews are at the top of the Muslims’ target list, but they’re not the only ones to suffer. With the tacit consent of the authorities, the Paris suburbs have become fertile breeding grounds for terrorist recruits.

On one day of my visit I asked my driver Reuven to drive me into the Muslim quarter. “Fifteen minutes and we’re out of there,” I promised. I wanted to look into the eyes of the incited youths, maybe get one to talk to me.

At the entrance to the market, one already got the sense that this was a third-world country, independent, sovereign, living by its own laws. At night, gangs of youths patrol the alleys, attacking any light-skinned stranger who unknowingly ventures in. The local underground is active after dark, run by radical Muslim groups who brainwash the young.

The police are well aware of what’s going on, but turn a blind eye to the grooming of an entire generation of terrorists within France.

“A not-insignificant number of ISIS volunteers came out of those neighborhoods,” says attorney Nataf. “The massacres at Charlie Hebdo and Théâtre Bataclan, in which hundreds of people were killed, were carried out by ISIS recruits from the Paris banlieues.

“The young are swept along. They see these terrorists as heroes, shahidim, and they want to share in the glory. As this terrible as this sounds, it was only when the white population started suffering too that the French caught on to the fact that this is a danger to everyone, not just the Jews.”

Lawfare in Paris

Oudy Bloch is a top Paris attorney. His firm represents financial institutions and high-tech companies in both France and the US. He tells us about the moment he decided to form a civil defense organization to protect the Jewish community and settle accounts with anyone who harms them.

“An acquaintance of mine was verbally attacked by a Muslim,” Bloch says. “When he complained to the police, they waved it off: ‘That’s not anti-Semitism, it’s just words.’ A citizen comes to a police station fearing for his life after suffering abuse and threats, but because the aggressors didn’t mention his ethnicity, the authorities won’t classify it as an anti-Semitic incident. It’s simply absurd. After all, the men chose to harass him, even though there was no prior acquaintance between them. The reaction he got spurred me to take action.

“We offer our services gratis and help anyone who turns to us. It takes up a lot of my time, but I feel a real sense of mission. We don’t just wait for incidents to happen, we have a whole team of communicators working on hasbarah on digital platforms.”

I ask Bloch if French hate crime laws cover only physical attacks, or if they also apply to verbal harassment.

“No, slurs also count,” he replies. “But proving it can be complicated. If the assailant didn’t use the word ‘Jew,’ it won’t be considered a hate crime, even if it’s clear from the circumstances that the motive was anti-Semitic.”

Bloch tells of a violent brawl that occurred several days previously between a gang of Muslims and some Jews, who fought back. “The police want to press charges against the Jews, simply because they managed to defend themselves against the Muslims’ aggression. The Muslims called out anti-Semitic pejoratives and hurled objects at them, but the Jews will be put on trial because they refused to turn the other cheek. We’ll protect them and be with them all the way until the indictment is dropped.”

By virtue of his position, Bloch is one of the attorneys who worked on the Sarah Halimi case. The outcry over that case still echoes in the pain in his voice.

“After a sham investigation and a deliberate disruption of the legal process, the court set a precedent by undertaking ahead of time to debate whether the killer was responsible for his actions at the time of committing the crime,” he says. “Instead of starting the trial and letting the defense make that case — and leaving the court to decide whether to accept or reject the argument — the prosecution, which is supposed to protect the victim and not the criminal, did the defense’s job for them before the trial even started.”

Jews Aren’t a Priority

Bloch’s comrade, Gregory Siksik, is a well-known lawyer in the French criminal justice system. “In day-to-day life,” he says, “ninety percent of cases I handle are for the defense. But not when it comes to anti-Semitism. There, I’ll always be on the side of the victim, and I’ll do it free of charge.”

One of the victims represented by Siksik was Yohan Cohen Hy”d, murdered in the Hypercacher terror attack on January 9, 2015. Muslim terrorist Amedi Coulibaly burst into a branch of the Jewish-owned supermarket chain in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, killing four and taking others hostage, triggering an hours-long standoff that ended when he was shot by police.

The shocking attack came two days after the massacre at the Charlie Hebdo offices in the 11th arrondissement, in which 12 people were killed. While the French police forces were moving in on the apartment of two of the Charlie Hebdo suspects, their ISIS accomplice Coulibaly broke into Hypercacher.

In the security video, the Hypercacher murderer asks a customer waiting in line what his name is; when he answers “Philippe Braham,” the terrorist promptly shoots him. Other footage shows François-Michel Saada trying to enter the store after Coulibaly’s rampage started. The shutters are closed, but he tries to enter anyway, despite the receptionist’s desperate signalling to him to stay away. When he realizes what’s going on, he tries to escape, but it’s too late: Coulibaly shoots him in the back and he falls to the ground. And all that time, store employee Yohan Cohen lay on the ground, bleeding to death.

“In court we were able to prove that aside from murder, when it came to Yohan, the perpetrator was also guilty of torture and leaving a wounded man to die,” says Siksik. “The murderer saw that Yohan was dying but he let him suffer, even asking the receptionist with a malicious smile if he should shoot him again or let him die in agony.

“When the judges asked one of the young Muslims who was involved in the attack: ‘Why did you do it?’ he responded without a moment’s hesitation: ‘We want to do to the Jews here what our brothers are doing to them in Israel.’”

Six years have passed. Siksik is still working with the Cohen family. He says that if not for the prosecution’s alertness, this case might also have ended in betrayal of the victim’s families.

“We put a lot of effort into the Hypercacher case,” says Siksik. “We were able to reconstruct the attack from a GoPro camera the murderer carried at the time of the crime. Screening parts of the video was difficult for the families in court, but helped us greatly with the sentence. Who knows? If not for that, the judges might have accepted defense arguments that here too the background was mental instability and not anti-Semitism.”

The lawyer’s veiled criticism of the legal process is matched by his indictment of the media coverage, which proved that for French elites, Jewish fear isn’t a top priority.

“When it comes to press coverage, too, I’m convinced that if it wasn’t so intimately connected to the Charlie Hebdo case, in which 11 non-Jews were killed, the Hypercacher attack wouldn’t have received such extensive coverage. That incident is unusual in the treatment it received from the authorities, because of the special circumstances. If it weren’t for the video in court and the perpetrators’ profile as the killers in the Charlie Hebdo massacre, we might currently be in the same position as the Halimi family.”

Systemic Anti-Semitism

Over the countless conversations I had in Paris with community members and Jewish leaders, the name “Sarah Halimi” came up again and again — along with the argument that the court’s ruling was itself motivated by anti-Semitism, not just the murder itself.

“A functional justice system has to first of all carry on an orderly legal process, file an indictment,” says Oudy Bloch. “If the defense wants to argue that the defendant was in the throes of a psychotic episode, they’re free to do so. But first, the judges need to hear the charges. Here, the killer wasn’t even tried. The prosecution did the job of the defense. If that isn’t anti-Semitism, what is?”

But there’s another, no less intriguing charge — and the two aren’t mutually exclusive — which is that the state apparatus is desperate to rebuff any claims about widespread anti-Semitism in France. In other words, while the French judiciary is denying Jews elementary justice, other parts of the establishment are keeping the lid firmly shut on the can of worms that is modern French anti-Semitism.

There are some, like Deputy Meir Habib, who haven’t given up trying to rein in the madness.

“I’ve demanded the formation of a parliamentary commission of inquiry into the Halimi affair,” he says. “I’ve already gathered the signatures of 70 National Assembly deputies who support the measure.”

But meanwhile, on the dangerous suburban Paris streets, judicial inertia has allowed radicalism to advance unimpeded. In places like Belleville, once home to Sarah Halimi, life isn’t waiting for official action. The Jewish population is now gone, and the sole shul converted into a mosque.

Remembering the Good

Four years after the attack that claimed his mother’s life, Yonatan Halimi refuses to dwell on his pain. He’s dedicated to commemorating his mother and performing good deeds in her memory on an extensive scale.

“I refuse to let this tragedy sink into oblivion,” he says. “Forty years ago she built a day-care center for preschoolers and raised hundreds of Jewish children in the heart of Paris. Chinuch, passing on tradition and unity — those were the values that guided her over the years. It’s my wish to honor her memory and ensure that her path and vision continue, so that the horrors of anti-Semitism only lead to a renewed flowering of Judaism.”

He’s currently busy founding a unique commemoration center, Ohel Sarah, dedicated to the encouragement of Jewish values among French olim in Israel.

“That’s the only revenge deserving my attention,” he says.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 864)

Oops! We could not locate your form.