Dark Meets Light

A train collision rerouted the Kook family to a new destination

Photos: Yedidya Meir archives

The personal churban of the Kook family over 50 years ago could have caused the surviving children to crumble, but the tragic train collision on the fourth night of Chanukah in 1971 — claiming the lives of Rechovot chief rabbi Rav Shlomo Kook, his wife and two children — became instead a survivor’s banner of emunah, hope, and growth. “We never felt like nebachs,” says Rabbanit Ziva Meir today. “We always thought about our role in spite of the circumstances”

W

hen 15-year-old Ziva Kook woke up on the fourth day of Chanukah in 1971, she couldn’t believe her bad luck. The entire family was looking forward to a day trip to Jerusalem, but she’d somehow contracted an eye infection.

Her father was Rav Shlomo Zalman Kook, the dynamic rav of Rechovot, who regularly traveled around the country as a sought-after Torah lecturer. He’d recently acquired a new car, and the rare family trip to Jerusalem would surely have been the highlight of Ziva’s Chanukah vacation: purchasing tefillin for her brother Uriel for his upcoming bar mitzvah, a tefillah at the Kosel, dropping off the manuscript her mother, Rabbanit Yehudit, had recently completed for a final proofreading before print, and then a Chanukah party in the home of their Katz grandparents.

But her swollen eye upended her plans.

“Seeing how upset I was, my father felt bad, and told me that if the doctor agreed, I could come along. But the doctor didn’t agree, and boy, was I furious,” says Rabbanit Ziva Meir, an acclaimed Israeli parenting expert and wife of Moshav Gimzu’s Rav Eliav Meir (and mother of media personalities Yedidya and Yitzchak Meir and another nine children), recalling that dark day over half a century ago, the day that would change her life forever. “But little did I know it meant that I would be saved.”

Rav Shlomo and Rabbanit Yehudit Kook collected their children, ten-year-old Yocheved, eight-year-old Menachem Don, and three-year old Nachman Nosson, and headed for Jerusalem. Uriel, 12, said he had a headache and stayed home with Ziva, and their brother Benzion — today a well-known posek, city rav and author of seforim — went to Teveria to be with their grandmother, Rabbanit Rachel Baila Kook, who was spending her first Chanukah alone after her husband, Teveria chief rabbi Rav Raphael HaKohein Kook, had passed away suddenly a few months before.

“I sat with Uriel at home,” Rabbanit Ziva recalls. “I wanted to make a surprise for my parents, so I took out a pot and made a batch of popcorn for them.” She had no idea that she’d never see them again.

An hour passed.

Then another.

It was long past the time to light the fourth candle, but there was still no sign of Ziva’s family. She and her brother waited and waited. Even some guests had already arrived — Rav Yehudah David Wolpe from Rishon Letzion and his family, who were invited for the evening after candle lighting.

A phone call to Rabbanit Yehudit’s father, Rav Dov Katz (author of the Tenuas Hamussar seforim series and one of the eminent students of Yeshivas Knesses Yisrael when it was still in Chevron) clarified that indeed, the Kooks had departed from Jerusalem long before dark and headed back to Rechovot.

Where were they?

While the Kook children were waiting for their parents to come home and light the fourth Chanukah licht, little did they know that the neshamos had already risen past the flames. Fifty years later, the hope and emunah is still flickering

ATthat moment, on the train tracks that cut through an orchard near Kibbutz Chuldah, the night sky was lit up with flashing ambulance lights. Rav Shlomo had decided to take a shortcut back to Rechovot, a route he regularly drove. But at the spot where the road intersected the train tracks, for some reason the electric barrier warning of an oncoming train wasn’t functioning — a safety failure that turned the tracks into a deathtrap.

The skies seemed to fall, as hundreds of sheets of paper flew through the air like a bursting cloud — it was Rabbanit Yehudit’s completed manuscript, a treatise on the stories of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov. At her side was a lifeless three-year-old Nachman, named for Rebbe Nachman who had broken into her deeply rooted litvish life. That was how the rescue teams found the bloody scene — typed pages scattered around wherever they looked.

By midnight, the children in Rechovot and the Katz grandparents in Jerusalem were sick with worry. The Katzes turned on the midnight news — a grim effort that perhaps would shed light on something that would explain the absence of their family members.

They didn’t have to wait long before the voice of the newscaster shattered their reality.

He reported a gruesome accident next to Kibbutz Chuldah involving Rav Shlomo Kook of Rechovot and his family. That’s how they heard about their children and grandchildren. It turned out that the police actually had informed a second-degree relative, but thinking that someone else in the family surely knew and not realizing that the police had essentially done its duty by informing him, the relative didn’t dare deliver such horrifying news himself.

“My grandparents in Jerusalem realized right away what had happened. But what happened in Teveria was even worse,” Rabbanit Ziva says. “My grandmother in Teveria was listening to the news, and she heard the names of the accident victims. She later said it was a miracle that neighbors who heard her shrieking came, because she felt like her soul was leaving her body. My brother Benzion, who awoke when he heard the noise, asked my grandmother what happened, but she didn’t answer him. Benzion turned to our cousin and said that something happened and Savta didn’t want to tell him.”

In the family’s home in Rechovot, relatives began to gather, including Rav Shlomo’s younger brother, Rav Simcha HaKohein Kook ztz”l, who came with his wife from Netanya (and who would take over the Rechovot rabbinate from his brother). Together, they began to put the children to sleep.

“They didn’t tell us yet what happened,” Ziva says. “We knew something had happened, but we didn’t know what, and I guess we were too frightened or overwhelmed to demand they tell us details. My aunt was there and told us go to sleep — I think she even gave me a little pill. When I woke up, the street in front of the house was packed with people, and so was the house. Then my uncle told me there was a train collision and asked me if I understood what that meant. He told me that my younger sister Yocheved was still alive, and that there was a small chance she’d make it.”

Looking back, Rabbanit Ziva says there was shock, but she doesn’t remember hysteria, doesn’t remember questions. “Shock, with a lot of emunah and bitachon. I don’t know else to define it. But suddenly, it was like I heard a voice inside me telling me that I had to prepare myself for my new role as the big sister. It was sort of like ‘hineini’ — here I am for my new job. I had to shoulder the responsibility. I didn’t really even have time to mourn — I just thought about who was going to deal with everything.”

Just half a year before the accident, she was witness to the way her father reacted to the sudden death of his father, Rav Rafael Kook. “When my grandfather had a sudden heart attack, I remember how my father received the news: He collected himself and went to Teveria. I learned a lot of emunah from them. They didn’t have to talk about it — I saw it in them, and I think that prepared me.

“We were a ‘whole’ family,” she continues, “not a ‘Holocaust’ family. That wasn’t so common back then — an Ashkenazi girl with grandparents and aunts and uncles on both sides. After the accident, friends told me they used to envy me, and now I had become an object of their pity. That was the last thing I wanted.”

There really was no time to mourn. Ziva spent her days juggling school and sitting at her sister’s side for a year, while Yocheved slowly — miraculously — recovered. (Today Yocheved is a busy mother and grandmother with 13 of her own children.)

That week, Rabbanit Rachel Kook of Teveria moved to Rechovot to care for her newly orphaned young grandchildren. She wondered perhaps if they needed a younger mother and not a 70-year-old grandmother. Rav Shach, who heard about her deliberations, reassured her, noting that he’d already passed the age of 70 (he was 72 at the time). “I’m getting old, but being in the company of the young yeshivah students keeps me young,” Rav Shach told her. “ That’s how it is: Alongside young people, you stay young.”

Years later, she herself related how at night, she would cry into her pillow. “But during the day, I knew that there were young children in the house, and they needed a happy grandmother. So I tried to radiate as much joy as I could.”

At Yocheved’s wedding, the lone survivor of the accident tearfully thanked her grandmother for all she’d done for her. “I don’t know who should be thanking who,” a now elderly Rabbanit Rachel replied. “Without you, I probably would have been in the cemetery next to Saba for years already. It’s only because I raised you that HaKadosh Baruch Hu gave me additional years, so that I could devote myself to you.”

And did Ziva’s grief ever come, even years later? “It took a long time. Maybe even years. My heart sort of shut down. Only much, much later was I able to go into that most painful place, which for years I didn’t let myself access. I really did not like pity. I developed an allergy to pity. So I guess that’s what gave me the strength to cope and to grow.”

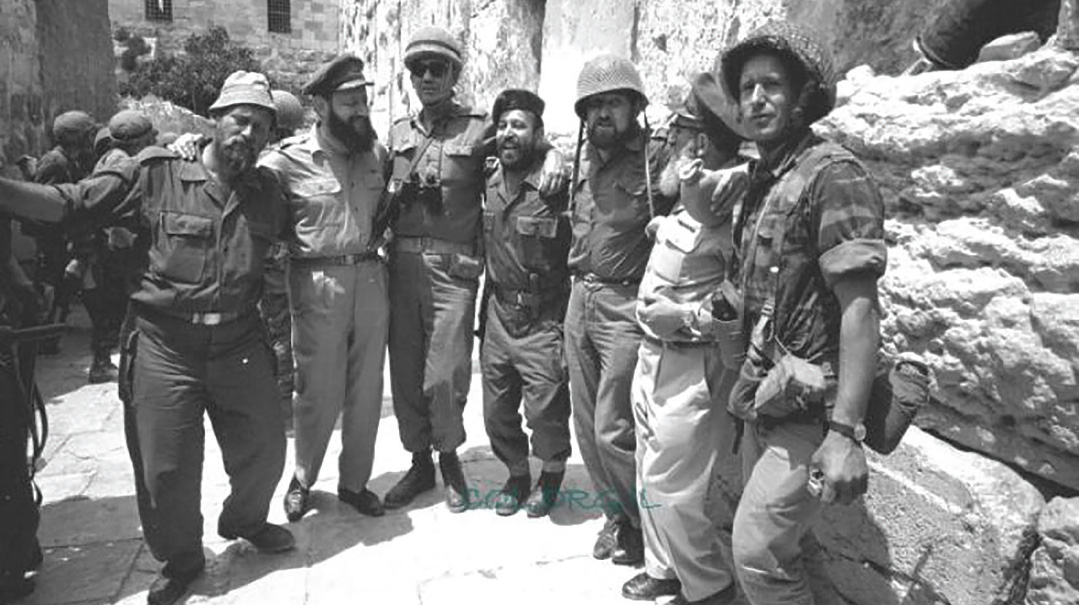

Rav Shlomo Zalman Kook, as a military rabbi (left) and rav and av beis din of Rechovot. He found a common language with the wide swath of the Israeli public

There was nothing routine about the life of Rav Shlomo Zalman HaKohein Kook. He was born in 1929 in the newly built Mandelbaum House, located on what would become the no-man’s-land in the heart of Jerusalem between the fledgling State of Israel and Jordan two decades later. His mother, Rabbanit Rachel, was a daughter of Reb Simcha Mandelbaum, a wealthy merchant who had raised his ten children in Jerusalem’s Old City but who needed a home with more space to accommodate his married children and guests. His father, Rav Raphael HaKohein Kook, a nephew of Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook, would become the longtime rav of Teveria.

As a teenager, Shlomo Zalman began his yeshivah education in Kfar Haro’eh, and then moved to Yeshivas Chevron. As an idealistic 16-year-old, he learned how to hide a pistol among his seforim, a weapon he used in underground Haganah operations during the War of Independence. Six years later, he met Rav Yerachmiel Eliyahu Botchko, rosh yeshivah of Montreux, Switzerland, who asked the 22-year-old to come and deliver shiurim at his yeshivah.

After a year in Switzerland, Rav Shlomo returned to yeshivah in Jerusalem, as per the advice of the Chazon Ish. He was also close to the Beis Yisrael of Gur, and went on to study dayanus after receiving semichah from Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank, Rav Yitzchak Herzog, Rav Shlomo Yosef Zevin and Rav Yechezkel Sarna, who wrote: “He is one of the giants of our yeshivah. He has much strength to affect others with brilliance and breadth, and he is capable of fighting the battle of Torah… there is a halo of chesed over him, and he is of noble soul and refinement, and gifted with sterling middos, he is beloved and pleasant and well-liked by others….”

Those characteristics made the young Rav Kook a popular figure among varied communities — he was invited to give derashos in venues from yeshivos to army bases to the Israeli Bar Association. An engaging speaker, he was able to connect with all types of Jews, finding a common language with those outside the world of the yeshivah.

In 1955 he married Yehudit, the daughter of Rav Dov Katz, a talmid of the Alter of Slabodka and an editor of the Alter’s shmuessen. But despite his trajectory in the rabbinic world, as a scion of the chain of rabbanim from the Kook family, he was drawn to the yeshivah world, He was asked to serve as rosh yeshivah in Ramsgate, England, where his oldest child, Ziva, was born. During the family’s three years there, he traveled often, including to Casablanca, Morocco to test students by invitation of the rav of Meknes, Rav Baruch Toledano.

His family members in Eretz Yisrael, meanwhile, were concerned for his welfare on his many travels. “I found your letter from Casablanca,” his father, Rav Raphael wrote to him. “And we are worried about your travels, because from afar, we don’t discern between the places, and any news of riots against Jews in the eastern countries makes us worry here at home.”

When the family returned to Eretz Yisrael, Rav Kook migrated from the yeshivah world to the army rabbinate, where he served as the military rabbi in the Jerusalem district for seven years. He also continued to learn dayanus and was appointed to the Tel Aviv beis din in 1965, before being appointed rav and av beis din of Rechovot two years later, which would be his final station.

Rav Shlomo Kook (second from left) merited to take part in the first minyan after the liberation of the Kosel. He was only in his thirties when he wrote a will requesting, when the time came, to be buried in the Jerusalem he cherished

HE was just 38, but the vote for the Rechovot rabbinic position was unanimous among the three dozen members of the appointment committee.

After the appointment was confirmed, a delegation from the voting body set out to Rav Kook’s home in the Tel Aviv suburb of Yismach Moshe to inform him that he had been elected. They were sure that the new rav would come with a whole list of requests, but were surprised to hear that he had only one: Because the municipality rents an apartment for the rav, he asked that it should be one that is easily accessible, so that even an elderly person would not have a hard time getting to his home.

Rabbanit Ziva Meir explains that her father made sure the home was accessible to everyone — that was part of his mandate. Their home was open to everyone, religious and secular alike, and she remembers how one day, an old, lonely woman came and cried to Rav Kook that she couldn’t manage in a nursing home. “What did my father tell her? That from that day on, she would live with us. And in fact, during the shivah, my grandmother who was taking care of us also found herself taking care of the elderly lady who my father had ‘adopted.’”

One day, after the beis din sessions were over, the guard dashed toward Rav Kook and told him that one of the butchers in the city was waiting for him and he was brandishing a knife. “I’m going to kill Rav Kook! He rescinded my kashrus!” the butcher had announced furiously. The guard pleaded with the Rav to lock himself in his office until the police came. The Rav’s escorts quickly shrank back in retreat, but he stopped them all. “There will not be a situation where a butcher threatens the Rav with a knife,” he declared firmly, and went forward unflinchingly. “We will continue, and the butcher will now get it over the head from me for this kind of conduct.”

He walked on, in the direction of the butcher shop, his escorts following nervously. The butcher ran toward them with the knife, shouting at the Rav. But Rav Kook stared him down without flinching.

“Put down the knife,” he ordered. “You will not speak that way to a rav.” The butcher was stunned. He had not expected this.

Not only was the Rav undeterred, he began to pound the butcher with mussar, and explained that in order to receive a kashrus certificate, there are very clear rules which are not to be deviated from. All at once the butcher’s face changed. He lowered his gaze, tossed the knife to the ground, and began to cry. “I need to support my family,” he wept. “I have five children and since the Rav took off the kashrus, I don’t have what to feed them.”

Rav Shlomo put a loving hand on his shoulder. “Hashem yishmor. If they don’t have what to eat, they should come to my house right now. I’ll take care of whatever they need.” And then he raised his voice. “But chas v’shalom, don’t think that in order to feed them you can destroy kashrus. I will not accept that.”

At Rav Shlomo’s engagement to Yehudit Katz, flanked by his father-in-law Rav Dov Katz (left) and his father Rav Raphael Kook.

AS

Rav Shlomo Kook’s life partner, Rabbanit Yehudit was also a rare blend of character traits and strengths. She was the daughter of a litvishe family of note, but was personally drawn to chassidus. She was a teacher in a Bais Yaakov high school by day, and in the evenings she studied with college students, many of whom who knew virtually nothing about Yiddishkeit.

“They were exceptional and very multifaceted parents,” Rabbanit Ziva relates. “It makes me laugh today to think that my mother was all of 38. So young. My father was 40, and he was considered a national leader. But with all his roles, he would use every spare minute to learn Torah. As a child, sometimes I was afraid at night, but when I heard my father learning Torah aloud it calmed me. And my mother, she was a lamplighter. At the time, I didn’t know this concept, but today, I can give it a name.”

She recalls the nights that that her mother spent writing her book. It was before the Iron Curtain fell, Uman was basically inaccessible, and Rebbe Nachman’s Torah was not as well known. When did she do all this?

“Instead of sleeping, she sat and wrote. We had a closed porch where the typewriter was, and you could hear her clacking away at it. My father was actually quite worried about her health, as she worked round the clock. And not just on the book. She wrote many essays and articles in both English and Hebrew. After the shivah, we found her drawers were stuffed with all kinds of writing, including Torah commentaries.

“My father spoke to my grandfather, her father, to ask what to do. And my grandfather, who had authored dozens of seforim himself, told my father, ‘Leave her be, this is her shlichus, her mission.’ She never merited to see the book published, but I think that by the time the sheloshim arrived, it had been published by the high school she worked in. It was pretty unusual: A young author writes a commentary on the depth and wisdom contained in the stories of Rebbe Nachman, and it was also accepted by the elders of Breslov and by the wider world. And this was at a time when the world of chassidus was actually very foreign to us.”

Rav Shlomo Kook receives warm blessings from Israeli president Zalman Shazar upon his appointment as a dayan in Tel Aviv (top); learning at home on a rare quiet evening. “Sometimes I was afraid at night, but when I heard my father learning Torah it calmed me”

AT the heart-wrenching levayah, the streets of Jerusalem turned black from the crowds following the four mittos. The levayah departed from the Kook home in Rechovot and continued to Yeshivas Chevron.

At the yeshivah, Rav Dov Katz wailed bitterly. “Dovid Hamelech eulogized his son, ‘Avshalom, bni, bni, Avshalom, Avshalom, Avshalom…’ Now that I have lost all that is dear to me, I, too, can only cry to my beloved ones, ‘Shlomo, my son, my son, Shlomo, Shlomo, Shlomo… Yehudit my daughter, my daughter, Yehudit, Yehudit, Yehudit… my beloved grandsons, Menachem Don and Nachman Nosson; Nachman Nosson and Menachem Don, my dear grandsons, Nachman Nosson and Menachem Don, Nachman Nosson and Menachem Don….”

Following the tragedy, there was a discussion about where to bury the family. The community in Rechovot felt that it was eminently fitting to bury the Rav and Av Beis Din in a dignified place in the city. Others felt Teveria, next to the Rav’s father, would be appropriate. But it was Rav Dov Katz who insisted that Har Hazeisim in Jerusalem was the most appropriate.

Sometime later, when Rav Shlomo’s desk was being cleared out in his office in Rechovot, his brother, Rav Simcha HaKohein Kook, found an envelope that had on it only the letter tzaddik in his brother’s handwriting. He opened it, and to his surprise, discovered a will, which his brother had written following some tests he had done a number of years earlier because of a health condition he was worried about.

“If possible,” the will stated, ultimately being fulfilled although no one even knew it existed, “I ask to be buried on Har Hazeisim in Jerusalem… Yefe nof mesos kol ha’aretz — where I was born and where I grew up, and where I merited to take part in its liberation and in the first minyan near the Kosel….”

Rav Benzion HaKohein Kook, who followed his father in the realm of rabbanus and dayanus, was just 11 when his parents and two brothers were killed, yet his remarkable growth germinated from the depths of anguish and orphanhood. Rav Benzion, who serves today as Rosh Beis Hahora’ah Haklali in Jerusalem and rav of central Petach Tikvah, was a talmid of Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapira and Rav Shlomo Wolbe, and was the first to compile a sefer of teshuvos of Rav Elyashiv, And he’s also an inspiration and backbone for other families who have suffered catastrophic loss.

He says he’ll never forget the first Maariv after his parents and siblings were buried. “The levayah began in Rechovot and then continued to the Chevron yeshivah in Jerusalem. The kevurah was only at night, and then the family returned from the levayah to the home of my grandparents, the Katzes, and davened Maariv. At first, they didn’t tell us that our family was killed, only that they were severely injured. So in the morning, I said the longest Shemoneh Esreh I’d ever davened. But by Maariv, there was no more pleading, no more making deals with Hashem. It was about helping me get through the pain.”

Decades later, when tragedies occur and there are young orphans, Rav Benzion Kook goes to the shivah house to give encouragement. After all, who can understand a young orphan better than he?

“I once went to comfort a grieving family after the parents of young children were killed in a car crash,” Rav Benzion relates, “The bereaved father/grandfather asked, ‘Because it looks like you experienced your years as an orphan in a good way, perhaps you can give me a few tips on how to act with my young grandchildren?’ I told him: ‘If I had ideas, I would gladly share them with you. But know, my friend, that Hashem gave us relatives who treated us with great wisdom. Ask my uncles — they’re the ones who can give you advice….’

“When my uncle Rav Yaakov Katz, heard this, he told me, ‘The uncles also didn’t have a clear plan of what to do. Only HaKadosh Baruch Hu is the Uncle. “Zeh Dodi v’zeh Re’i.” And this Uncle guided us through every detail.’”

“By Maariv, once they were buried, there was no more pleading, no more making deals with Hashem. It was about helping me get through the pain.” Half a century later, Rav Bentzion HaKohein Kook is filling his father’s huge shoes and comforting others along the way

TO his children, Rav Shlomo Kook left a second tzavaah that was eerily prophetic, even though he was only in his 30s: He instructs them to be happy and not to mourn overtime. “If, chas v’shalom, I will not merit to be with you, if it is decreed from Above that we have to separate, then we need to strengthen ourselves and trust in Hashem, Who is so great and compassionate, and in Whose Hands we are all sustained, with mercy and benevolence, as He is the Father of orphans and the Judge of widows….”

More than 50 years later, is the tragedy still present in some form, keeping Rabbanit Ziva company throughout life?

“Well, there’s the conscious and the subconscious,” she says. “My daughter asked me a while back, ‘Ima, don’t you think that the fact that you invest so much in the family and in parenting courses for others is because of the tragedy?’ I looked at her and told her that I honestly don’t know. Of course, subconsciously, the home and the family have become very significant and important and present. From my father and mother, I took the emunah, the knowledge that the Creator plans everything. I also learned from them the importance of connecting with all of Klal Yisrael.

“But I never thought about the ‘would’ve, should’ve, could’ve’ piece. This is the way Hashem wanted it to play out, what He determined for them and for us. I think that despite our tremendous pain as children, we were still able to feel that our parents had completed their shlichus. Today I know how to say it in nice words. When I was a girl, with the void and all that I lacked, I think I still felt it even though I didn’t have the vocabulary to express it.

“I remember very clearly how amid all the people and the tumult that was there that Chanukah morning, I said to myself that if chalilah such a thing would happen to someone, I would tell them that despite it all, it is possible to survive. In various therapy modalities I’m involved in, I show people that an individual, with siyata d’Shmaya, can take himself from within the deepest crisis to all kinds of places of growth…. I too could have gone to a place of despair.

“Even when we speak about the next generation, the grandchildren of Rav Shlomo Kook, they don’t see themselves as ‘the second generation since the accident.’ They didn’t live in the shadow of that horrific event and it was never something that clouded their lives. Rather, it was more like the strength to forge on, taken from all the strengths they left us.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 942)

Oops! We could not locate your form.