Crypto Crunch

Once feted as a visionary and philanthropist, Bankman-Fried’s wealth was built on lies

Sam Bankman-Fried’s meteoric rise to crypto-currency greatness ended in an epic downfall amid the collapse of his FTX firm. As the crypto industry reels, does the underlying blockchain technology have a future?

S

am Bankman-Fried still can’t understand what happened to him — or at least that’s what he wants us to think. When the disgraced founder of the FTX cryptocurrency exchange was escorted out of the courtroom following the denial of his bail request last week, he seemed dazed. After all, he was only trying to help — all his money was made in the cause of “effective altruism.” But again, maybe that’s just what he wants you to think.

Just three months ago, 30-year-old Bankman-Fried was the subject of a fawning, 14,000-word profile by the Sequoia Foundation (which Sequoia has since deleted, but the Internet remembers everything). The author of the piece predicted Bankman-Fried would become the world’s first trillionaire, hailing him as the herald of a new economic era.

Now the crypto world’s darling is in prison, facing charges of fraud and money laundering as well as violation of campaign financing laws. If convicted on all counts, he could receive up to 115 years in prison. Currently detained in the Bahamas — where he lives — and facing extradition to the US, his plea for a $250,000 cash bail release was denied due to fear that he would use the opportunity to escape.

How did the crypto world’s wunderkind morph into the crypto world’s Bernie Madoff?

The answer is the weakest link of all: people. Or rather, their misplaced trust.

In Code We Trust

It’s now 14 years since the blockchain technology gave the world its first and most successful cryptocurrency to date, Bitcoin. According to Satoshi Nakamoto, the mystery designer (or designers) of the technology, Bitcoin obviates the blind trust necessary for fiat currencies — i.e., currencies backed by nothing but governments’ promises to honor them — as all transactions made with it are recorded on a public ledger anyone can access.

The blockchain is a public ledger of transactions maintained by a peer-to-peer network rather than a central authority. New transactions are recorded in “blocks,” which are broadcast out to every node participating in the network, on thousands of personal computers across the world. The nodes evaluate the validity of every new block they receive. If it’s valid, the new block is added to the blockchain. A record of the new transactions then exists in each node’s copy of the blockchain, meaning that it can’t be tampered with.

New blocks are broadcast to the network in a process called mining. To create a new block, miners have to solve increasingly complicated computational puzzles (a system known as “proof of work”), for which they are awarded a number of new Bitcoins as compensation. Because the blocks are linked — each block contains the solution to the previous block’s computational puzzle — the proof of work system makes retroactive tampering with the ledger practically infeasible, as it would require the defrauder to redo the computations for every single block later in the chain. The resulting immunity from fraud has led to slogans such as “in code we trust” among crypto enthusiasts.

This has attracted both tech-oriented people who see all software code as cool and futuristic, as well as those trying to hide their financial transactions from the government, from tax evaders to drug traffickers and ransomware hackers.

Despite its volatility, the crypto world has thrived. People “trust in code,” and many were excited by the mystique surrounding the new digital currencies. And wherever there’s money, companies will spring up to profit from it. Enter FTX.

FTX, founded by Sam Bankman-Fried (widely known by his Twitter handle, “SBF”), made it possible to trade in digital currencies and derivatives without restrictions. To finance its activities, the digital exchange issued the FTT currency — providing benefits in trading fees to anyone who owned FTT and traded through FTX. Bankman-Fried, a Jew who graduated in physics and mathematics from MIT, was working in the traditional capital market, when he discovered the possibility of making a huge fortune in the field of crypto through a tool borrowed from his world: arbitrage.

In his first job, Bankman-Fried built complex models to profit from tiny price differences between securities on various exchanges, when he discovered that the price of Bitcoin can vary by as much as ten percent. In 2017 he founded Alameda Research, and began profiting off the difference between Bitcoin prices in the United States and Japan. With an initial investment of $10,000, he made a billion dollars in a few months. Alameda became a “hit” that generated hundreds of thousands of dollars a day. Even when that particular arbitrage opportunity ended, others arose, and Alameda was quick to take advantage of them.

But Bankman-Fried didn’t hoard his newfound wealth to himself. He became involved with the ideology — a more polite term for cult — of “effective altruism,” which advocates an evidence-and reason-based approach to charity and benefiting others. In his first years at Alameda, Bankman-Fried gave about half of his six-digit salary to charity to animal rights organizations, among other charitable organizations. His goal, he told everyone, was to make as much money as possible, with a view to giving most of it to charity, leaving only one percent of his earnings — or a minimum of $100,000 a year — for himself.

Rumors of his success at Alameda spread, and when he founded the FTX exchange in 2019, investors came flocking. He became a sought-after speaker, and high-profile Hollywood stars and sportspeople featured in FTX’s advertising. In 2021, FTX’s revenue hit $1.1 billion, a net profit of $350 million. Leading investment firms invested in the company, which reached a peak market cap of $32 billion. Bankman-Fried was a multibillionaire, at least on paper.

He managed his companies from the Bahamas, where he lived in a penthouse with a number of coworkers in a commune-like arrangement. Despite his luxurious residence, he spent most of his time at the office, getting in only a few hours of sleep a day.

His ability to generate money gave him the halo of success, and many predicted he would become the world’s first trillionaire. The “altruism” he talked about was also reflected in his business dealings, as he stepped up to rescue more than one crypto company that ran into difficulties.

And none of his investors, it seems, took a moment to look into how he ran his business, or what was behind his sudden boom. The trust in code vanished, replaced by old-fashioned trust in a charismatic individual. And that was the little rift within the lute, with repercussions not only for the crypto world but the blockchain technology in general.

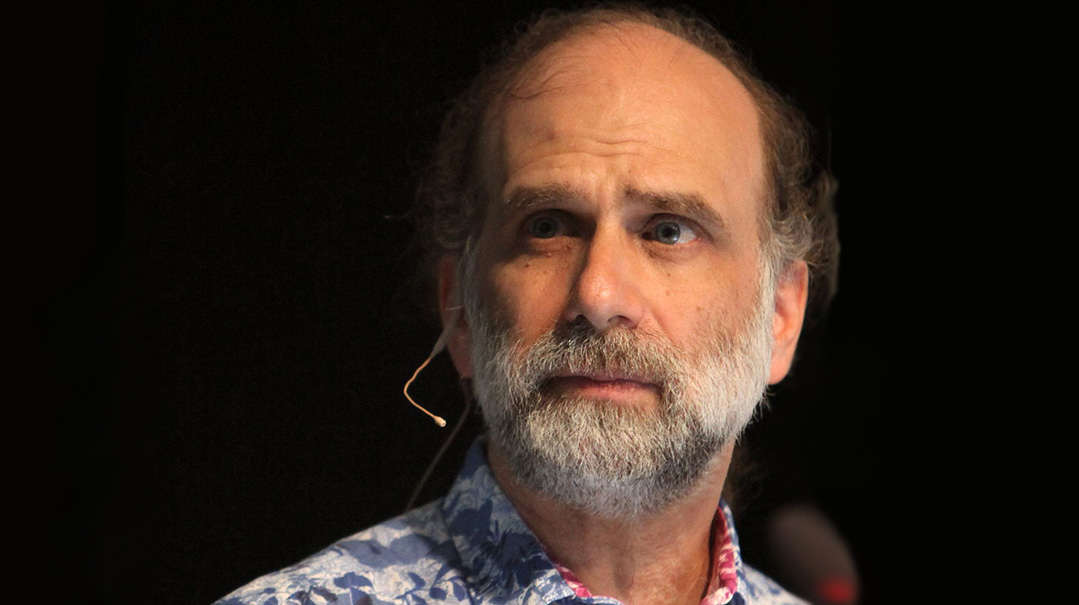

This crypto-crush was envisioned back in 2019 by Bruce Schneier, a public-interest technologist, a lecturer in public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and a fellow in some other security and public policy institutions. The Economist calls him a “security guru.”

“What blockchain does is shift some of the trust in people and institutions to trust in technology,” he wrote then. “You need to trust the cryptography, the protocols, the software, the computers, and the network. And you need to trust them absolutely, because they’re often single points of failure… A false trust in blockchain can itself be a security risk.”

ROBBER BARON Once feted as a visionary and philanthropist, Bankman-Fried’s wealth was built on lies (Photo: Youtube screenshot)

Window Dressing

The hype surrounding the blockchain technology hasn’t remained confined to cryptocurrency. Over time, other industries have found applications for the new technology. The point is that just as monetary transactions can be recorded in blocks, other types of information — such as shipping manifests — can as well, obviating the need for paperwork.

Software giant IBM rushed to open a blockchain department in 2016. Arvind Krishna, then vice president of the company’s research division and now its CEO and chairman, said that through extensive digitization of the documentation process in the shipping world, it would be possible to use blockchain to transfer information in a secure, efficient, and (most importantly) inexpensive manner.

“We believe that this digitization alone will save tens of billions of dollars,” Krishna said at a conference on blockchain held in the summer of 2017.

Many companies prospered on exactly this promise — that the blockchain technology would increase efficiency and security in any number of fields.

But everything has a price. In the crypto world, that price is first and foremost the sheer amount of energy necessary for the mining computations.

“Bitcoin has the most expensive consensus algorithm the world has ever seen, by far,” wrote Schneier in 2019.

Moreover, says Schneier, the technology never fulfilled its promise.

“It was never promising,” he tells Mishpacha a few days after Sam Bankman-Fried’s arrest. “It was never true.” And to this day, so many years after the technology was introduced, “there is not a single application that is viable.”

The problem, Schneier muses, is that blockchain was a great idea that never found the proper outlet.

“Blockchain was always looking for a solution,” he says. “No one ever said, ‘I have a problem — oh, look, Blockchain is the solution.’ People said, ‘I have a blockchain — oh, look, there’s a problem.’

“Every company that claims to use blockchain actually doesn’t,” Schneier says. “They started using it, they realized it’s stupid, they removed it quietly. They keep it around, because this is how they get funding, this is how they get press, but it is not actually essential, it’s this window dressing. It was the cool thing, but it doesn’t actually do anything, it doesn’t actually work.”

Such was the case for IBM’s blockchain division and the Maersk shipping company’s start-up using blockchain on shipping manifests. “It just died, nobody wanted to do it,” Schneier says.

Before he wrote his 2019 essay, Schneier tells Mishpacha, “I went through the whole thing — it doesn’t do anything they claim it does. It’s not distributed, it’s not secured, and it’s never been secured.”

For starters, he says — the “decentralized” part that attracts so many people does not exist.

“There are a lot of centralized pieces. There is one blockchain, that’s very centralized. There are what — two, three exchanges? Mining is done by six companies, that’s it. It’s incredibly centralized.”

On the other hand, Schneier charges, those flocking to the blockchain hoping to protect their anonymity will find that it does not live up to the hype, due to the nature of the public ledger.

“The FBI is increasingly able to track down ransomware perpetrators,” he points out, citing an example. “Despite the supposed anonymity of the blockchain, where everything is secure and once you do something, you can’t undo it, the FBI is becoming really good at recovering these ransoms.”

Bruce Schneier “Crypto will probably fade into obscurity” (Photo: Rama)

Fatal Flaw

It would be easy to dismiss Schneier as a prophet of doom, but his predictions have come true with startling accuracy. Most crypto enthusiasts simply dismissed him as a fusty old conservative, and crypto mania continued in full swing. Anyone seeking to attract investment only had to pronounce the magic words “crypto” and “blockchain.”

The result was a seemingly limitless flow of money into crypto companies, with every entrepreneur in this field getting a hearing and a seat at the table. Bankman-Fried, the “wunderkind of the crypto world,” was the ultimate example of this.

To a large extent, the keyword for the crypto market’s fate is hubris. The story of the industry’s explosion over the past year is a story of old-fashioned chutzpah. The fact that cryptocurrencies, along with blockchain technology, became magic words in the financial world allowed many people to get rich from cheap money. The feeling in the market was that you could party as if there were no tomorrow — and that the party was going to last forever. People capitalized on this feeling to get rich, but also to gain political influence and fame.

For Sam Bankman-Fried, hubris was reflected in, among other things, FTX’s acquisition of the naming rights to the Miami Heat NBA team’s arena. In March 2021, he concluded a $135 million deal with Miami-Dade County for 19 years. Now that he’s been arrested for fraud, one can’t help but wonder: How much of this money actually belonged to his investors?

The Israeli crypto company Celsius was similarly afflicted. It applied for Chapter 11 bankruptcy last July, leaving behind 300,000 creditors and $4 billion in debt. This followed huge fundraising, when the company had already long known, according to documents released in courts in recent months, that it couldn’t meet its commitments. The company presented itself as a “crypto bank”; it gave unreasonably high returns on customers’ deposits, claiming that they were using clients’ funds to invest in crypto and mine Bitcoin, relying on a currency that they themselves issued.

Nine months before its collapse, already deep in a state of insolvency that it wouldn’t admit, according to the documents, Celsius heads were interviewed by Calcalist, the business magazine of Yedioth Ahronoth, and threw around statements that in retrospect are astonishing for their mendacity. The reporter didn’t go easy on them and asked difficult questions, but with breezy confidence, they answered, “For us, only three things are certain — death, taxes, and Celsius’s interest payments.”

The atmosphere within the company was revealed by one of the employees in an interview with the Israeli economic newspaper Globes after the company collapsed.

“I saw enormous waste, salaries completely disproportionate to the market, endless perks for employees, high-end office equipment, and no one counted our hours in the office!” the employee said. “We started to feel like we were in control of the world’s money and that we could never run out of it.”

Celsius was indeed controlling too much money — but the gravy train finally ran out, and some investors wrote heartbreaking letters to the court about the life savings they lost.

The hubris was also expressed in Sam Bankman-Fried’s shamelessness, as he repeatedly called for more transparency and regulation in the market. In stark contrast to most in the crypto market, he spoke publicly about the need for regulation, even testifying in Congress about the need for transparency in his industry.

Bankman-Fried began to contribute massively to political campaigns, becoming the Democratic Party’s biggest donor after George Soros. He donated to some Republicans as well. His goal was obvious — to purchase the power to influence policy. He aired his political views constantly, and policy-makers were pretty close to giving him whatever he wanted. As far as is known, his total political contributions reached up to $73 million.

According to Damian Williams, US attorney for the Southern District of New York, all of SBF’s contributions came from embezzled customer funds. At some point, Bankman-Fried had begun to use a “backdoor” in the code of his stock exchange to transfer customer funds to finance Alameda’s activities. On November 2, 2022, crypto news site CoinDesk published a report revealing that Alameda was highly leveraged, and that a large part of its capital was held in FTT, the currency of its sister company FTX — not a financially stable arrangement.

In the wake of the CoinDesk article, competing crypto exchange Binance announced that it was selling its FTT tokens. That triggered the crypto equivalent of a bank run. As a result, mass withdrawals began, with $6 billion being withdrawn in one day. After FTX filed for bankruptcy, the bitter truth emerged: Bankman-Fried had transferred $8 billion of the company’s customer funds to Alameda.

In interviews conducted since the fall, in an attempt to clear his name, SBF seemed sincerely sorry, declaring that he would do anything to return the funds, but also claiming that he had no idea how exactly the illegal money transfers worked. One might say he was trying to pass the buck.

Last Tuesday Bankman-Fried was supposed to testify before Congress about what happened, but he was arrested by the Bahamas authorities the night before following a US extradition request. After it came out that his money was invested in so many politicians, some speculated that the extradition was deliberately accelerated so that he wouldn’t reveal embarrassing details in his Congressional testimony. The White House, as of now, refuses to comment on the question of whether the campaign contributions will be returned, but it appears that the prosecution will aim for that.

CHUTZPAH FTX’s corporate sponsorships were a sign of the hubris at the company and in the wider crypto industry (Photo: AP images)

Land in Florida

With the downfall of FTX, the hundreds of thousands of people who lost their money received a sharp reminder of how unsafe the crypto world can be, especially when the digital currency is stored centrally rather than in physical “wallets,” which are a kind of hard disk on which the currency information is stored. In the days following FTX’s collapse, the exchange was hacked and $650 million was stolen. A claim surfaced that the hack occurred from within the company, though that has yet to be confirmed.

That wasn’t the first theft, needless to say, just as FTX’s wasn’t the first bankruptcy. In October alone, more than $760 million in cryptocurrencies were stolen, reported PeckShield, a blockchain security company.

Bruce Schneier believes these events pose a question about the future of the crypto world.

“Will it go away? Probably,” he says. “Increasingly, the regulatory authorities are bringing it under the auspices of financial systems. They’ll be able to do it in places where real money touches cryptocurrency, so it loses its special status. They are getting better in tracking criminal uses. So it’s going to lose its value for ransomware and terrorist financing. For those two reasons it’s going to be like everything else, nothing special. And then it will probably fade into obscurity. It will still exist, but if no one buys and sells it, it will die.”

Schneier says one of blockchain technology’s main weaknesses is its need for miners in order to maintain viability.

“In order to work, cryptocurrency has to be speculative,” he says. “There must be a steady stream of buyers, otherwise mining is not profitable. If mining is not profitable, transactions don’t happen. If you lose that, the whole system collapses. So as soon as more people think it’s going to go down than up, it just dies.”

Schneier makes clear that by “death,” he means shrinking to its “natural dimensions.” History is full of economic bubbles that collapsed — for example, he cites the Florida land boom of the 1920s, which ultimately subsided. Did the real estate market in Florida disappear? No, he says, it was just that the investment fever passed.

In the meantime, he agrees that as long as the crypto world continues to generate hype, people will invest in it. There’s a lot of money in it, and certain actors have an interest in promoting it with all they’ve got. But in the long run, he predicts, it will fade away — and that’s a good thing.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 941)

Oops! We could not locate your form.