Crown Jews

Ties past and present between Britain's monarchy and its Jews

As Britain’s Jews will be marking this week’s “Coronation Shabbos” with kiddushim, special tefillos for the peace of the kingdom, and an invitation for the chief rabbi to stay with King Charles over the weekend in order to attend, the historical record tells of different, more challenging times: of occasional protection by the king and relative stability, but also of expulsions, pogroms and mass murders. A millennium timeline of survival

When King Charles III is crowned in Westminster Abbey this week, it will be in a ceremony whose central moments are drawn from the Tanach.

Screened from the thousands watching inside the ancient building, and the vast audience expected to watch the media coverage, are the moments when the king is anointed — a ritual harking back to the coronation of Shlomo Hamelech by Tzaddok HaKohein, as recorded in Sefer Melachim (interestingly, the haftarah of this week calls the Kohanim “Bnei Tzaddok” in a reference to that early Kohein Gadol.)

So conscious is the echo of the Jewish kings of old that the oil used for the ceremony was produced on the Mount of Olives to emphasize the source of the tradition, which British monarchs have followed for centuries.

But while Shabbos will prevent an audience of Britain’s notably royalist Jews from tuning in, the Biblical motifs highlight a relationship between the Crown and the Jewish community that dates back almost one thousand years.

It was Charles’s ancestor, Norman duke William the Conqueror who invited French Jews to live in England after he wrested control of the country from the last Saxon king in 1066.

Over the millennium since, Jews have drifted in and out of British history. First came communities headed by famous Baalei HaTosafos, then expulsion, a centuries-long absence, and a renewed presence. In the modern era, Jewish aristocrats like the Rothschilds and politicians like Benjamin Disraeli made their mark on the country and its royals.

In a sense, the story of Britain’s kings and Jews is the long arc of the rise of liberalism in the country. Because one thousand years after William, whose power base was today’s coronation venue Westminster Palace, his descendant’s decision to invite Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis to stay with him over Shabbos to enable the chief rabbi to attend the coronation (see sidebar) is a sign of the official respect that today’s Jewish community enjoys.

As Britain’s Jewish communities mark the Coronation Shabbos with kiddushim and — in some cases — a special tefillah for the event, the following is a gallop through ten centuries of Royal-Jewish history.

I’m joined by Rabbi Aubrey Hersh, longtime lecturer at London’s Jewish Learning Exchange and host of the popular podcast “History for the Curious” in an (unscientific) attempt to highlight the villains and heroes, eras and trends of a relationship that began all those years ago, back when English Jews spoke French.

1070

England’s Jewish history begins with a conquering king. The first written record of a Jewish settlement in the country dates to 1070, four years after William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy in western France, defeated England’s King Harold, inaugurating a French takeover of the Saxon kingdom.

As the Norman nobility asserted control over England, William needed money to fund his newly elevated status as English king and invited Jewish merchants from Rouen, Normandy, to join him as financiers. These French-speaking Jews settled in the southeast of England, gradually moving toward London and then across England and Wales, where they’d stay for two centuries until the expulsion of 1290.

The terms of the relationship were clear: Jews served as financiers and were ruthlessly taxed — providing almost half of all tax revenue at one point. In return, they came under the king’s protection — an arrangement that was the best to be hoped for in medieval times.

Although the Jews worked in trade, as doctors, artisans, and financiers, their imprint on Jewish history goes beyond their business activities. Normandy was home to the Baalei HaTosafos, and some of the rabbanim who came across to England to serve the growing Jewish communities take a place of honor in the beis medrash until today as the Tosafos Chachmei Anglia.

“Nowadays, from the perspective of a physical presence — shuls, cemeteries, mikvehs — very little remains,” says Rabbi Aubrey Hersh. “It’s a different story when we come to documentation of day-to-day life, especially business records. Over 300 documents in Hebrew have been published, which account for only a small portion of the ones making their rounds in medieval England. In Durham Priory to this day, there are five Hebrew documents from the 13th century relating to the activities of Aaron of York, a wealthy Jew.

“Fascinatingly, all these contracts gave rise to a word for contract — ‘starr,’ from the Hebrew shtar — entering the English vocabulary in the Middle Ages. The shtar Jews created would be written in Hebrew (sometimes entirely) — even when lending money to a non-Jew — and countersigned by both sides.”

Court Jester

William the Conqueror’s son and successor on the English throne, William Rufus — so named for his red hair — was an irreverent character who was content to give Jews latitude that was unusual in many parts of medieval Europe.

A sense of William’s relatively tolerant — and impious — attitude to the Jews is captured by British Jewish historian Cecil Roth in his landmark History of the Jews in England.

“On a certain solemnity when the Jews of London brought him a gift,” Roth notes, “he persuaded them to enter into a religious discussion with bishops and churchmen present at court. Not content with the scandal caused by this, he jestingly swore that if they were victorious, he would himself embrace Judaism — an impiety which can hardly have enhanced their popularity in ecclesiastical circles.”

1158

The high point of medieval Jewish life in England came with the Charter of the Jews issued by William the Conqueror’s grandson, King Henry II, who extended his grandfather’s charter of protection, formally granting the Jews the privilege of internal jurisdiction in accordance with Talmudic law, except in the case of offenses against public order.

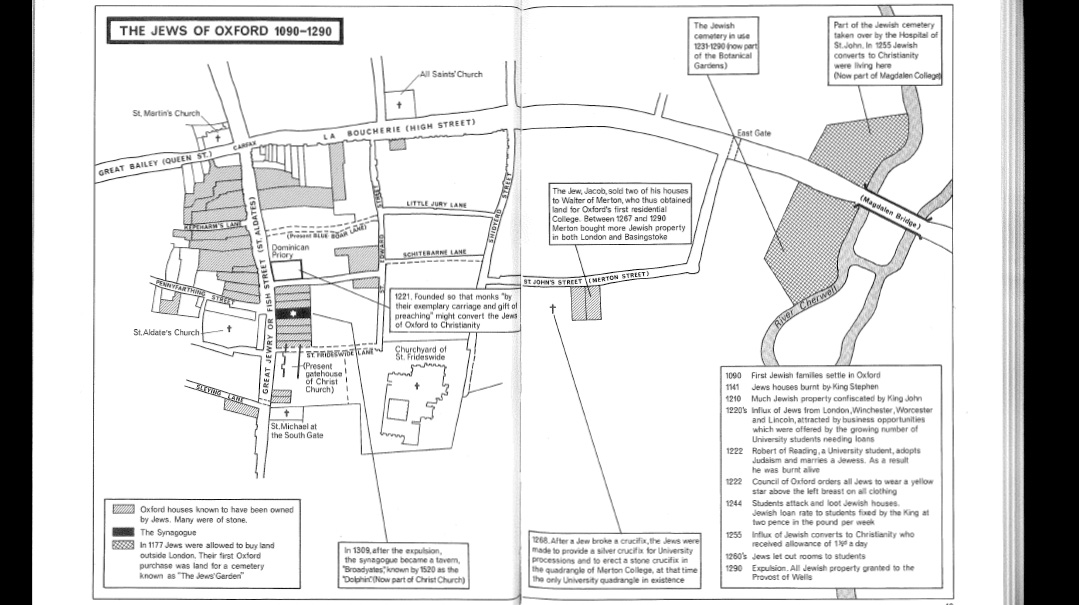

By this point, there was a fully functioning community in London and Oxford, each located within streets with names such as Street of the Jews or Jewry Street.

All burials from across England had to take place in the single cemetery allocated to them in London. Jews were, however, permitted to build synagogues. They were also allowed to place their womenfolk and children in the monasteries for safety at times of disturbance.

The pre-expulsion community was never very large — numbering perhaps 10,000 people at its peak — but it was by and large a peaceful existence.

English Jewry’s relative tranquility is in stark contrast to the upheavals taking place in France and Germany in the same period. Across the Channel, the First and Second Crusades played out in 1096 and 1145, with all the horrors and destruction that the Christian warriors inflicted on their Jewish neighbors.

Shabbos Sleep

1158 was also the year in which Rav Avraham ibn Ezra visited London and composed his famous work, Iggeres Shabbos, which dealt with the correct time for bringing in Shabbos.

The background to the work was a dream that the Spanish-born rabbi had one Friday night, in which a messenger from Shabbos itself rebuked him for holding in his possession a book that propagated the old Karaite idea that Shabbos begins in the day.

Shaken, the Ibn Ezra woke up and searched his room, discovering that the dream was true and that the heretical book was indeed there.

That Motzaei Shabbos, he sat down to write a sefer defending the authenticity of Shabbos as celebrated from time immemorial.

Rabbi Aubrey Hersh in the Barbican on the yahrtzeit of Rav Yaakov of Orleans. The garden was the location of the original cemetery for London Jewry

1189–1190

At a reported 1.96 meters tall, Richard the Lionheart was — both literally and metaphorically — the giant figure of medieval England. A true warrior king, he led his armies into battle from the front, defeating the Muslim leader Saladin in showdowns that were the centerpieces of the Third Crusade.

His impact on Jewish life was felt not just in the Holy Land, but at home in England, beginning with trouble at his coronation in 1189, which led directly to the infamous massacre of the Jews at York the following year.

“From the start things didn’t bode well for the Jews,” says Rabbi Hersh. “A proclamation was issued that no Jew could attend — somewhat different from the coronation of King Charles this year — but when a deputation of Jews nevertheless presented itself at the entrance to Westminster Hall in the hope of obtaining a renewal of the charter of privileges, things turned ugly.”

Several members of the deputation were beaten or trampled to death by the crowd at the palace gates. Benedict (a Latinization of Baruch), a wealthy moneylender who had come to represent the Jewish community of York, saved his life by consenting to embrace Christianity, and was immediately baptized.

News of the upheaval at Westminster soon spread and it was rumoured that the king had given orders for the Jews to be killed. A mob headed to the Jewish quarter of London. Those living in stone houses were able to resist for some hours but toward nightfall, one of the mob set fire to the thatched roof of one of the sturdy homes. The flames rapidly spread, and soon the whole of the Jewish area was ablaze.

“Thirty Jews lost their lives,” says Rabbi Hersh, “among them one of the Baalei HaTosafos, Rav Yaakov of Orleans. He was buried near the Barbican, an old fortification in London in a location which isn’t commemorated at the site itself, but which is clearly marked on maps of the period.”

But worse was to follow. In the crusading fervor that had at last gripped England as the king prepared to battle the enemies of Christendom, a rash of pogroms took place across the country.

The riots culminated in the massacre of the Jewish community in York in 1190, in which the famous Rav Yom Tov of Joigny lost his life, leaving behind the Tosafos he authored as well as “Omnom Kein,” a moving piyut sung by Ashkenazim on Yom Kippur.

Charta Judaica

Like many a strong father, the Lionheart’s brother King John, who took power in 1199, was of a rather more faint disposition. He is remembered as the man who grudgingly gave his subjects some measure of liberty in the shape of the Magna Carta, seen as a foundational document in the evolution of the rule of law.

Not as widely known is the fact that early on in the Charter’s 62 clauses were two that specifically targeted Jewish moneylenders, limiting the financiers’ power to collect interest from a deceased borrower’s estate.

But while the Magna Carta was no document of Jewish emancipation, in the long run it achieved precisely that, setting off a process that centuries later would grant Jews freedom that neither King John nor his rebellious barons could imagine.

1278

By the 1270s, the writing was on the wall for English Jews. Already in 1253, King Henry III had issued the Statute of Jewry which codified anti-Semitic legislation. It mandated that Jews wear a badge on their clothing to identify them as Jews. The statute also said that no new synagogues could be built, and restricted the ability of Jews to live outside of Jewish communities.

Then, in 1275, Edward I banned moneylending with interest — known as “usury” — thus destroying the main Jewish livelihood.

“The pretext for widespread action against the Jews arose in 1278,” explains Rabbi Hersh, “when 600 Jewish men were arrested and imprisoned in the tower of London on a charge of coin-clipping (cutting off some of the silver from a coin and still passing it off at its full value).

“If that number of household heads were imprisoned, and their number is multiplied by 3.5 or four to allow for wives and children, you arrive at a Jewish population of between 2,000 and 3,000 individuals, which is very likely at that time.”

The final nail in the medieval Jewish coffin was hammered in 1290 when King Edward issued the Edict of Expulsion. It is often said that the Jews were expelled on Tishah B’Av, but while the expulsion order was signed in July, the Jews were given until All Saints Day (November 1) to leave.

A small number stayed in England, either converting to Christianity or keeping their faith a secret, and the rest left for the European mainland to settle in new countries.

The Jewish presence that had begun two centuries before was over, and for 350 years, virulently anti-Semitic Christian England was free of Jews.

Money Troubles

In the coin-clipping episode that triggered English Jewry’s downfall, says Rabbi Hersh, Jews weren’t entirely blameless.

“There is a teshuvah addressed to a rabbi in London written by the Maharam of Rothenberg, the leading halachic authority in Germany at the time, about coin-clipping, which shows that it was practiced by members of the community.

“It was written sometime toward the end of the 1200s, and addressed an unsavory practice wherein Jews forced to take an oath that they would not clip coins made a mental note which they believed had invalidated the oath.”

“The Maharam explains at length why the practice is both against halachah, and a danger to the Jewish community, and concluded by urging his London correspondent to act strongly against the law-breakers.

“Therefore, if your authority and my authority carry enough weight, these Jews should be properly flogged.”

1655

In the centuries after the Expulsion, Jews weren’t entirely absent from England. Favored individuals such as doctors for the royal court were invited over. After the curtain came down on the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, growing numbers of Marranos settled in London, secretly practicing their religion and mostly tolerated.

It was in the absence of a king that the first official overtures for Jewish readmission to England took place. As Parliament asserted its independence from the sovereign, King Charles I was executed in 1649 for seeking to roll back the liberties of the people.

Parliamentary forces, called “Roundheads” under General Oliver Cromwell, seized power.

Rabbi Menasheh ben Yisrael, a scholar and diplomat who viewed the struggle for Jewish rights through a Messianic lens, arrived in London in 1655 to present a plea to Cromwell and the Parliament for the readmission of the Jews to England. Although he was favorably received, he passed away before his mission was completed.

It was only in 1664, after the restoration of the monarchy and during the subsequent reign of Charles II, that the Jews were formally granted the right to return.

The first to arrive were the Sephardim, mainly from Holland, and in 1690 an Ashkenazi community opened in London.

The oldest synagogue in London — Bevis Marks — dates from 1701, to which Queen Anne donated a large oak beam, which is still in place.

These changes took place at a time of growing religious tolerance in England. The new thinking was typified by the writings of John Selden, a Christian jurist and scholar of Jewish law.

1744

With the passage of almost a century, Jews were firmly established enough in England to lobby for the rights of their coreligionists elsewhere.

On December 1, 1744 the leaders of the Prague Jewish community wrote in great distress to leaders of Jewish communities all over Europe that Habsburg ruler Queen Maria Theresa had decreed the expulsion of all Jews from Bohemia and Moravia.

In London, two of the Ashkenazi leaders — wardens of the Great Synagogue Moses Hart and Aaron Franks — obtained an audience with King George II and begged the king’s intervention.

It was a sign both of Jewish political influence, and the fact that well into the 18th century, the monarch still occupied the top of the political pyramid — a far cry from today’s ceremonial role.

The results were striking. On the day of the audience, the Secretary of State, Lord Harrington, wrote to the British Ambassador in Vienna, Sir Thomas Robinson:

“The principal merchants of the Jewish nation here having made an humble application to His Majesty that he would be pleased to intercede with the Queen of Hungary… it is the King’s pleasure that you should join with the Netherlands envoy in Vienna in endeavouring to dissuade the Court of Vienna from putting the said sentence in execution… His Majesty does extremely commiserate the terrible circumstances of distress to which so many poor and innocent families must be reduced, if this edict takes place.”

Robinson kept in close touch with the Jews of Vienna; one of their leaders wrote to Prague: “The King of England… has sent an express courier hither with another urgent letter of intercession, and this courier waits here especially for the answer. I cannot express on paper how urgently the King has written.”

Salvation to Kings

The prayer for the Royal Family that is etched in stone in the front of many English shuls and which is recited before Mussaf on Shabbos, echoes Rav Chanina’s statement (Avos, 3,2): “Pray for the welfare of the government, for if not for its fear, one man would devour his fellow.”

In other words, a world without proper governance is a world of anarchy.

The Mishnah in fact echoes an earlier source. Yirmiyahu Hanavi recorded a prophecy from Hashem telling him, “Seek the welfare of the city to which I have exiled you, and pray — to Hashem — on its behalf; for with its peace, you will have peace.”

The Kol Bo in early 14th century Provence says that on Shabbos, after the haftarah, “There are places where they bless the king and then the congregation.” That statement locates the current practice in terms of where in the tefillah it is fixed.

At the end of the 15th century, siddurim began to appear with a formalized prayer for the monarch which begins with the well-known phrase: “Hanosen teshuah lamelachim u’memshalah lanesichim — He Who gives victory to kings and dominion to princes.”

It is a poetic prayer, drawing heavily on verses from Tanach. We do not know who composed this prayer, but a short time after its appearance, it had become popular across the European continent.

According to Rabbi Aubrey Hersh, when Rabbi Menashe ben Yisrael lobbied in the 17th century for the return of Jews to England, he cited this prayer.

1875

But it was a baptized Jew who got the closest to British royalty, argues Rabbi Hersh. Benjamin Disraeli, born in 1804 to a family with Italian roots, became prime minister in 1868 with Britian at the height of its imperial power under Queen Victoria.

Disraeli showed his political nous by feeding the Queen with Parliamentary gossip. In 1877, when she paid him a royal visit, he sawed the bottom two inches off his dining room table so that when the vertically-challenged Queen sat there, her feet would reach the floor rather than dangle.

Disraeli, known as ‘Dizzy,’ presided over a foreign policy coup that involved the deployment of the Rothschilds’ vast financial firepower.

In 1854 the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps had obtained a concession from the viceroy of Egypt to construct a canal which would dramatically improve international shipping times.

When debts forced the viceroy to put up his country’s shares for sale in 1875, Disraeli learned of this, and started efforts to purchase the stock for Britain and stop it from falling almost entirely to the country’s strategic competitor, France.

Since parliament was in recess, he could not use the country’s wealth to purchase the shares. So, he approached a Jewish friend, Lionel Nathan de Rothschild to secure the necessary sum. When the deal was concluded, Disraeli had 44 percent of the shares of the company for the price of £4,000,000 — or £365,000,000 in today’s currency.

Disraeli told the Queen: “It is settled, you have it, ma’am!”

To many non-Jews, it was clear that Benjamin Disraeli’s baptism — undertaken before the law barring Jews from political office was abolished — was insincere.

“You were born a Jew and you forsook your great people,” Queen Victoria exclaimed to her favorite prime minister. “Now you are a member of the Church of England, but no one believes that you are a Christian at heart. Please tell me, who are you and what are you?”

1908

But it was a baptized Jew who got the closest to British royalty, argues Rabbi Hersh. Benjamin Disraeli, born in 1804 to a family with Italian roots, became prime minister in 1868 with Britian at the height of its imperial power under Queen Victoria.

Disraeli showed his political nous by feeding the Queen with Parliamentary gossip. In 1877, when she paid him a royal visit, he sawed the bottom two inches off his dining room table so that when the vertically-challenged Queen sat there, her feet would reach the floor rather than dangle.

Disraeli, known as ‘Dizzy,’ presided over a foreign policy coup that involved the deployment of the Rothschilds’ vast financial firepower.

In 1854 the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps had obtained a concession from the viceroy of Egypt to construct a canal which would dramatically improve international shipping times.

When debts forced the viceroy to put up his country’s shares for sale in 1875, Disraeli learned of this, and started efforts to purchase the stock for Britain and stop it from falling almost entirely to the country’s strategic competitor, France.

Since parliament was in recess, he could not use the country’s wealth to purchase the shares. So, he approached a Jewish friend, Lionel Nathan de Rothschild to secure the necessary sum. When the deal was concluded, Disraeli had 44 percent of the shares of the company for the price of £4,000,000 — or £365,000,000 in today’s currency.

Disraeli told the Queen: “It is settled, you have it, ma’am!”

To many non-Jews, it was clear that Benjamin Disraeli’s baptism — undertaken before the law barring Jews from political office was abolished — was insincere.

“You were born a Jew and you forsook your great people,” Queen Victoria exclaimed to her favorite prime minister. “Now you are a member of the Church of England, but no one believes that you are a Christian at heart. Please tell me, who are you and what are you?”

The Rabbi and the Abbey

After the Christian component of this week’s coronation ends, King Charles will receive a greeting by Jewish, Hindu, Sikh, Muslim, and Buddhist leaders.

The move is in keeping with Charles’ stress on interfaith unity, and will be notable for the fact that microphones won’t be used to broadcast that part of the ceremony. The reason, notes the BBC, is “because the Chief Rabbi will be observing the Jewish Shabbat which prohibits the use of electricity, including microphones.”

While that is a kingly gesture of tolerance, what of the fact that the chief rabbi himself will be attending a service in Westminster Abbey, which is after all a church?

A historic — but hazy — tradition points to a heter given to generations of chief rabbis to attend such events, in the name of Kavod Hamalchus and the inability to reuse an invitation to attend which is construed, in the royal context, as something more than a gracious request.

In a conversation with Mishpacha, a senior source in the London Beis Din confirmed the existence of this generations-old psak, but pointed to another compelling angle.

“We in Britain are fortunate that for historic reasons, the Orthodox Chief Rabbi remains the official community representative, recognized by the government.

“If we were to refuse an invitation to the Coronation, non-Orthodox representatives would happily fill the gap to the detriment of Yiddishkeit in the country. Preventing that situation is a halachic imperative as well.”

1947

If relations between the Crown and the Jews had been on an upswing ever since the country opened its doors again to them in the 17th century, it was the long reign of Queen Elizabeth II that remains uppermost in the community’s mind today.

Jews — overwhelmingly middle-class in the second half of the 20th century — identified strongly with the dignity and conservatism of “The Queen,” as she was known.

Enthusiasm for her coronation was international, a taste of which is apparent from the Forverts — at one time America’s leading Yiddish newspaper with a circulation of 275,000.

In 1947, the paper covered the wedding of Prince Philip to Princess Elizabeth with an article headlined, “Di Kenigliche Chassuna,” making it probably the only paper that described the royal couple as “der Kallah” and “der Chosson.”

Elizabeth’s reign was notable for the integration of the Jewish community, with record-breaking numbers of Jews serving in Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s (prompting one Conservative Party politician to call her cabinet “more Old Estonian than Old Etonian” — a reference to the Jewish politicians’ Eastern European roots).

With the monarchy reduced to a ceremonial role by the last century, that level of integration owed more to the triumph of liberalism than any royal influence.

But it was ultimately the monarchy that over the generations had acquiesced to the general spirit of tolerance which ultimately brought about the change in the Jewish community’s position.

Thanks to that sense of tolerance and warm regard for the Jewish community, there were many occasions when religious Jews — from Chief Rabbis to dayanim and the occasional Israeli diplomat — were hosted at the royal palaces with kashrus teams brought in to ensure the comfort of the guests.

But perhaps it was the chareidi community that paid an oblique but warm tribute to the late Queen’s standing.

One thousand years after her forebear had brought Jews into the country as royal chattel, and as Britain secularized, Queen Elizabeth became the only symbol of British culture that penetrated the furthest reaches of chareidi life in the country.

“Operation Golden Orb” a.k.a. the Coronation

There’s nothing quite like the pomp and pageantry of a British coronation… except the avodah in the Beis Hamikdash, which much of the British coronation traditions are clearly influenced by. May we soon witness it anew!

The Arrival

King Charles and the Queen Consort will travel to Westminster Abbey in the Diamond Jubilee State Coach, in what is called the King’s Procession.

The Venue

Westminster Abbey has been the site of British coronations for over 950 years. William the Conqueror (1028–1087) was the first documented coronation at Westminster in 1066, but the first king to be crowned in the present abbey was Edward I (1239–1307) in 1274. Since 1066, 39 English and British monarchs have been coronated “at Westminster.” King Charles will be the 40th.

The Chair

The crowning takes place in the coronation chair (also known as St. Edward’s Chair or King Edward’s Chair). The chair was commissioned by Edward I in 1296.

The Crowns

Charles III will be crowned with St. Edward’s Crown, made for Charles II in 1661. It’s made of solid gold and 444 gemstones (including rubies, amethysts, garnets, sapphires, tourmalines, and topazes), weighs nearly five pounds, and is 12-inches tall.

Queen Camilla will wear Queen Mary’s crown, which is made of silver and gold, and has 2,200 diamonds on it.

The crowns are far from the only bling used in the ceremony. The Royal Regalia is the term used for the sacred objects carried or worn by the king or queen during their coronation.

The Coronation Spoon

Dating from the 12th century, it’s the oldest item in the ceremony, used to anoint the king’s head with holy oil. All the older regalia was destroyed or sold between 1653 and 1659. The Yeoman of Charles I’s wardrobe, Clement Kynnersley, bought the spoon, however, and returned it to Charles II to use at his coronation in 1660.

The Guest List

The coronation of King Charles III will be much smaller than Queen Elizabeth’s; she had 8,251 guests, but he’s only inviting 2,000.

The coronation includes five main elements:

The Recognition

The king stands in the theatre (Westminster Abbey’s central space) and turns east, south, west, and north to show himself to the people.

The Oath

The Archbishop asks three questions of the monarch and the oath is taken. At the altar, the sovereign touches a Bible and says, “The things which I have here before promised, I will perform and keep. So help me G-d.” The oath is then signed.

The Anointing

The head of state is blessed with anointing or “chrism” oil during the ceremony, made with oil from Har Hazeisim.

Until now, this oil contained animal products. For Queen Elizabeth II, for example, the anointing oil used was made with products from several animals, including a musk deer, a civet cat, and a sperm whale.

In 2023, however, the oil will be vegan-friendly, with a secret blend of olive oil, sesame, rose, jasmine, cinnamon, neroli, benzoin, amber, and orange blossom.

This reflects King Charles’s well-known attitude toward animals, as he is the president of the WWF (World Wildlife Fund, the leading organization in wildlife conservation and endangered species), and has a long history of campaigning for animal rights, which includes calling for a war on poachers and banning foie gras from royal menus.

The anointing is the most sacred part of the coronation service, the king wearing a simple white shirt, representing that he comes before G-d as a servant. It will not be televised but hidden from the public, as it was for Queen Elizabeth’s coronation in 1953.

The Investiture

Now sanctified, he is presented with the coronation regalia, sacred and secular objects that symbolize the service and responsibilities of the monarch.

The Crowning and Enthronement

The Archbishop of Canterbury brings St. Edward’s crown from the altar and places it on the sovereign’s head. The king then sits on the throne wearing his crown.

Aftermath

The king and queen will return to Buckingham Palace in the gold state coach, built in 1762 to transport British kings and queens, and used at every coronation since William IV’s in 1831. It will travel at walking pace due to its age (261 years) and weight (4.4 tons).

And then, the king, queen, and senior members of the royal family will stand on the Buckingham Palace balcony. Since 1902, the coronation day finale has been a balcony appearance.

Who pays for the coronation?

Unlike a royal wedding, a coronation is a state occasion. That means the government pays.

More on the history of English Jewry by Rabbi Aubrey Hersh can be found at the History for the Curious podcast: www.jle.org.uk/podcast

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 959)

Oops! We could not locate your form.