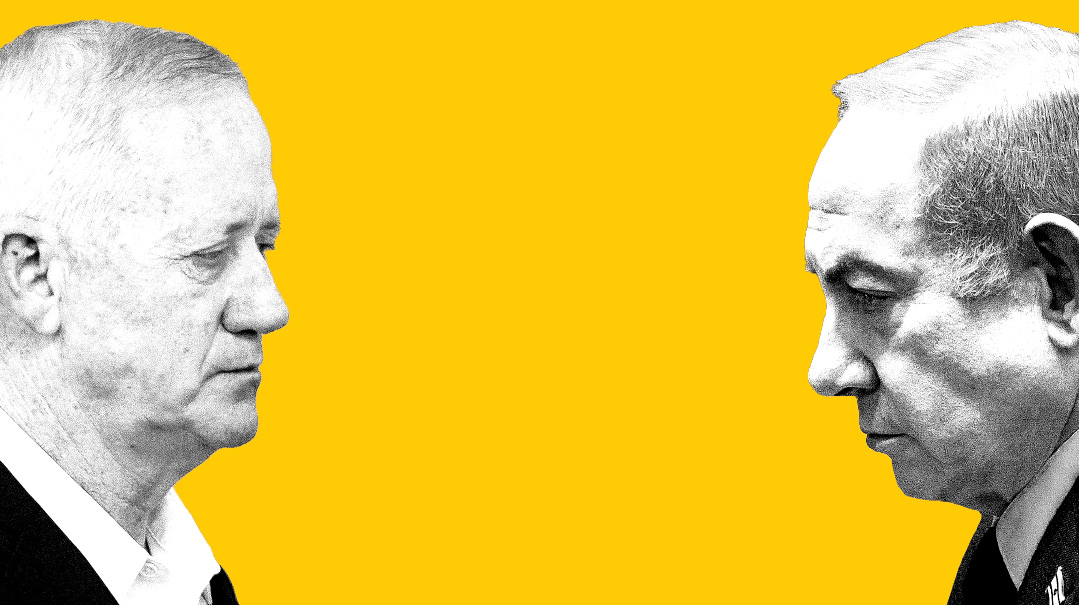

Court of Injustice

When sending Aharon Barak to the Hague, Bibi had an eye on Biden

Photo: AP Images

1

For a display of hypocrisy incarnate, you couldn’t do better than the hearings that began last week at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague, on South Africa’s claim that Israel is committing genocide in its war on Hamas.

Even a hardened cynic would struggle to grasp so vicious a perversion of justice; massacre victims are portrayed as the aggressors in this conflict, with the tacit approval of international observers. All this, even as over 100 abductees still languish in Hamas’s tunnels, and their kidnappers, presented as victims, feel so confident in the enlightened world’s sympathy that they release a hostage video a day before the start of the hearings.

The term of office for each of the 15 members of the ICJ’s standing panel is nine years, more than twice the tenure of a two-term American president. Just as the composition of Israel’s Judicial Selection Committee determines the character of its High Court, the bodies that select ICJ justices — the UN General Assembly and Security Council — tell you everything you need to know about that operation.

Why did Israel agree to participate in so blatant a show trial? This is a question that’s frustrating Jews all over the world.

Historically, Israel’s approach to the ICJ and other international tribunals has been reminiscent of the well-known legal argument made by chareidim from the Old Yishuv: “Eini makir [I don’t recognize the court’s authority].” Israel has never fared well in the legal proceedings held against it in various international fora, but there’s a key difference between the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Israel is not actually a signatory to the Rome Statute that established the ICC. Israel did, however, sign the ICJ statute in 1950, when the furnaces of Auschwitz were still smoldering, and no one even imagined that anyone could charge the children of Holocaust survivors with genocide. As a party to the ICJ, Israel must acknowledge the court’s jurisdiction.

2

Israel’s signing of the ICJ statute in the early days of the state was the main reason Netanyahu decided to contest the charges, but it wasn’t the only one. Netanyahu explained in closed talks this week that Israel can’t expect an automatic American veto in the Security Council if it shows no willingness to defend itself in court.

In the past, Israel has boycotted proceedings against it at the ICJ on less volatile issues such as the security fence, resulting in a 14-1 result to its detriment, with only the US judge siding with the Israeli position.

However, the difference between the security fence issue and the current charge lies not only in the severity of the charge, but also in Israel’s legal standing. Israel only recognizes the ICJ’s authority with regard to the specific crime of genocide, which is defined under the Genocide Convention as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.”

History could not be more ironic. In retrospect, Israel’s recognition of the court regarding this one charge is what has tied its hands. The signing of the statute, intended to guarantee “never again,” is harming Israel even as the axiom itself was shattered and the horrors of the Holocaust came back to haunt its survivors and their descendants.

Determined to railroad Israel, South Africa couldn’t settle for less serious charges such as war crimes or crimes against humanity, which the International Court of Justice also hears. Israel is accused of no less than genocide precisely because of its longstanding choice to recognize the court’s authority on that issue.

The South African team bases its case on two main arguments. First, documentation of the destruction in Gaza based on photographic evidence and individual testimonies, and second, quotes from Israeli politicians taken to imply that Israel’s main war aim is the destruction of Gaza.

The lawsuit stars irrelevant public figures and backbench Knesset members, but also selected quotes from Prime Minister Netanyahu, President Herzog, and Defense Minister Galant. In this war, and in reversal of the admonition in Pirkei Avos, most senior Israeli officials have said much even as they do little.

3

AS soon as South Africa announced the addition of the vice president of the South African Supreme Court to its lineup, Israel had to call up a “big league” persona of its own. Former High Court president Aharon Barak, the leader of the fight against the judicial reform, seemed a perfect choice, as someone who experienced firsthand the horrors of the Holocaust and has been seen as Israel’s most internationally respected jurist for decades.

The first to suggest him was Ron Dermer, whose acquaintance with Aharon Barak began somewhere in the late 1990s. Bibi himself was at a low point then, only slightly better off than today, after his stinging loss to Ehud Barak (not to be confused with Aharon) in the 1999 election. Dermer, who to this day mostly speaks his native English, but in those years barely understood Hebrew, was then an up-and-coming columnist for the Jerusalem Post. As a “concerned citizen,” Netanyahu sensed the potential in Dermer’s columns on geopolitical matters, and cultivated a relationship with the young writer. He would end up becoming Bibi’s most loyal advisor for over two decades.

At the same time, Aharon Barak, then president of the High Court, had hired a clerk with an unusual background: a graduate of Yale Law School raised in Baltimore’s frum community named Rhoda Pagano. It turns out that Barak’s talents aren’t limited to the legal realm; he also has considerable ability as a shadchan. Barak introduced his American clerk to Ron Dermer, which led in good time to a bayis ne’eman b’Yisrael.

In closed talks held in an attempt at damage control, Netanyahu explained that the choice of Barak — seen as a figurehead of last year’s judicial reform protests — was a necessary evil. The short time frame and the real prospect of immediate provisional measures calling for an end to the fighting meant that Israel had to act fast.

Netanyahu’s attitude about Barak is the same as his attitude to the pilots sent on sorties in Lebanon and Gaza. In wartime, you send the best soldier to do the job, without looking into his political history. The octogenarian Barak was clearly the soldier best placed to serve Israel at the Hague. One can only hope that this expectation, like Israel’s hopes in so many areas over the past months, won’t shatter on the rocks of reality.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 995)

Oops! We could not locate your form.