Connecting the Dots

Every now and then, Dr. Michael Steinhardt surprises you with a flash of passion. Like the colors in his office, everything about the neuropsychologist is gentle: voice, appearance, manner of speaking.

But when discussing the chinuch self-help industry — purveyors of herbs and other remedies for a variety of childhood ailments — or the number of children misdiagnosed with ADHD and other behavioral issues, you see the glint in his black eyes, hear the edge in his voice.

“Let’s say a child shows signs of being ADHD, so the parents get a prescription for Ritalin. Simple, right?” Dr. Steinhardt tells me animatedly. “But really, it’s not so simple. More than half of children with ADHD are affected by another comorbid condition, which means, in layman’s terms, that ADHD doesn’t usually come alone, but along with other issues.

“Now, if a child has ADHD plus, but is only treated for ADHD, it’s almost as if he hasn’t been treated at all!”

The stakes are too high, Dr. Steinhardt says, to get it wrong. So for the last six years, he has quietly changed the way kids with behavioral issues are diagnosed, applying a comprehensive exam, plenty of patience, and the full picture of a child’s life to assess the symptoms so prevalent in schools today that every child knows the acronyms by heart.

A prominent menahel described Dr. Steinhardt’s methods this way: It’s like when you take your car to the mechanic for an oil change, and he notices an unrelated problem with the fan belt. The extra expense and bother is a nuisance, but you are nevertheless grateful for the information. Smart mechanics suggest an all-points inspection just to uncover these kinds of hidden problems. In much the same way, Dr. Steinhardt assesses children’s behavioral problems, looking for the obvious symptoms, the hidden causes, and all the while uncovering unexpected ailments.

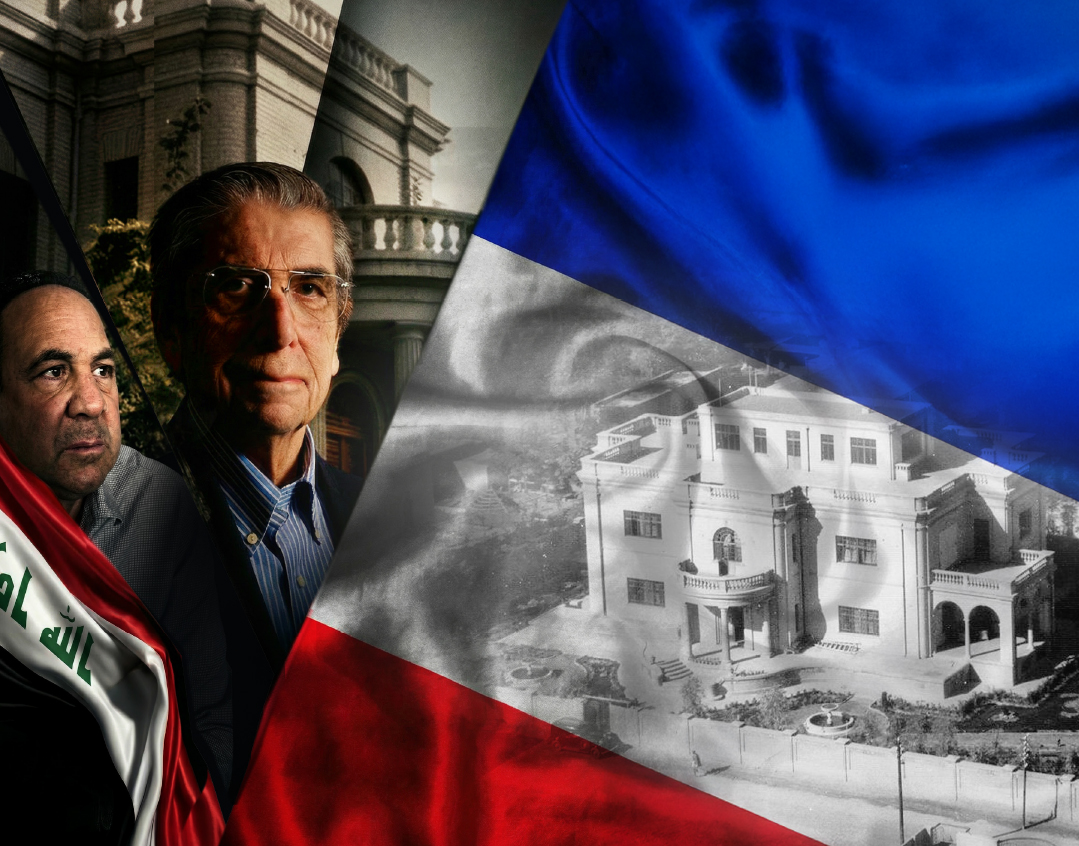

For anyone familiar with Dr. Steinhardt’s family, his accomplishments in the realm of education should come as no surprise. Because along with the unruffled professionalism, the impressive résumé of training and accomplishments, there is also his yichus, a family tradition that imbues him with a streak of advocacy and spirited defense for the rights of every child. And while he learned medicine in university, he learned chinuch at the feet of a master.

Your Shtender a Slabodka

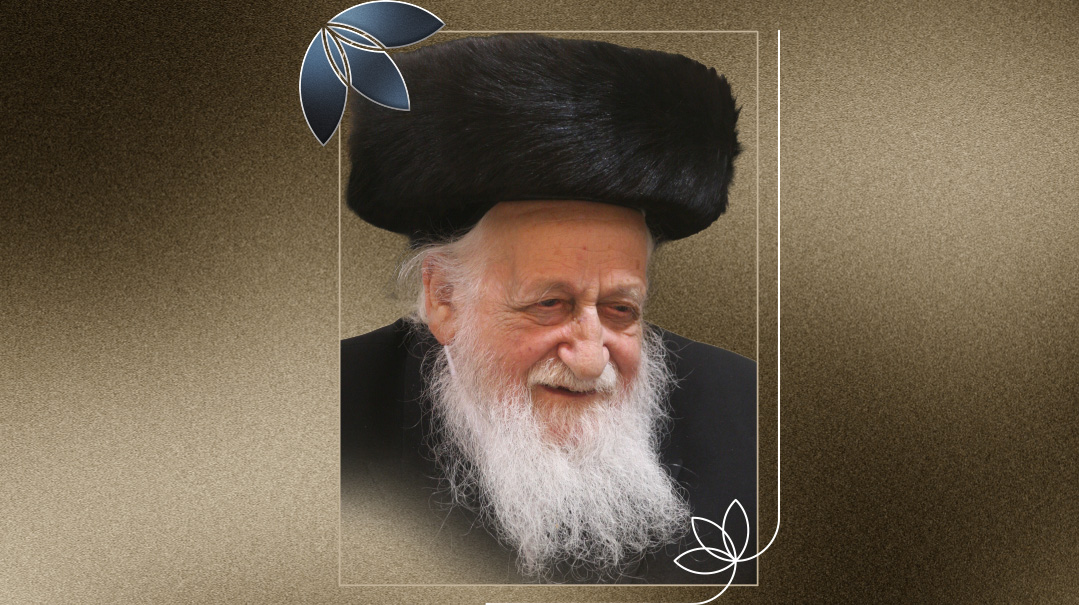

On the office wall there is a picture of his grandfather, Dr. Joseph Kaminetsky. It is not mere decor, but a mission statement, as relevant as the many diplomas. Dr. Joe, as he was lovingly known, was tapped as a young man by Reb Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz to serve as national director of the organization that Mr. Mendlowitz referred to as “mein liebling,” my darling, Torah Umesorah.

A man of learning, eloquence, and passion, Joseph Kaminetsky’s doctorate from Columbia University gave him credibility in the homes of parents across America, in the cities and towns where he’d been charged with establishing Torah day schools.

Over the second half of the last century, Dr. Joe succeeded in setting up hundreds of schools, using his passion to persuade locals that their town needed authentic Orthodox education, lending his efficiency to the cause of maintaining these schools.

But there was something else fueling the educator in his tireless efforts: the vision of Slabodka.

How did a child of East New York come to absorb the values of personal grandeur and dignity of the European yeshivah?

In 1932, the Slabodka rosh yeshivah, Rav Eizek Sher, son-in-law of the Alter of Slabodka, came to America to raise funds. Unproductive as was his trip financially, it was successful in another realm: the Rosh Yeshivah became a magnet for a small chaburah from Yeshivat Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan. Drawn to his ideas and personality, they formed a weekly vaad with the visiting Rosh Yeshivah: some, like Avigdor Miller and Mordechai Gifter, actually traveled back to Europe to learn in the great yeshivos. Others, like Joseph Kaminetsky, weren’t as fortunate.

Having lost his own father, he wasn’t able to leave America, and was devastated at what he saw as a lost opportunity. Reb Eizek comforted him, kissing the bochur on the forehead and saying, “Make your shtender into Slabodka.”

Just a Moment

Sitting in his office in Montvale, New Jersey, Dr. Steinhardt recalls just how literally his grandfather took the mandate. “I grew up around him, my parents lived right near my grandparents in Boro Park, and I learned with him. We learned the sefer Ohr Hatzafun, the writings of the Alter of Slabodka.

“It was a culture of chinuch, the insights he shared, the conversations, even the people coming through his house — Rabbi Nachman Bulman, Rabbi Sender Linchner, Rabbi Eliyahu Kitov… it was fascinating. He revered the gedolim, and after the passing of Reb Shraga Feivel, he attached himself to people like Rav Hutner, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky.”

In addition to this early exposure to the fathers of modern Torah pedagogy, young Moshe Steinhardt also learned another truth about education. “Both my parents are special educators, so I would notice the people coming over to my father after davening, ‘just for a moment,’ to ask him a question. I realized that in our community, chinuch is everything, and parents will do whatever it takes to help their children. My father understood the vulnerability of a parent whose child doesn’t fit perfectly into a box — who has a reading problem, learning disability, or behavior problem — and he was always gracious in trying to help.”

What I Wanted to Do

After graduating high school and learning in Eretz Yisrael for a year, Steinhardt was at a crossroads. He spent the summer of 1981 in Camp Mogen Avraham, where he met the legendary menahel of Baltimore’s Ner Israel Rabbinical College, Rabbi Naftali (Herman) Neuberger.

“He asked me why I didn’t come learn in Baltimore, and I told him that I wasn’t yet sure what I wanted to do,” Dr. Steinhardt recalls. “Rabbi Neuberger said, ‘Because of who your grandfather is, I will make you a special offer. You can come to us for Elul, and if you like it, you’ll stay, otherwise you’ll move on.’ ”

Moshe Steinhardt became a talmid at Ner Israel, and remained there for six years, both as a bochur and a member of the kollel. He also studied for his bachelor’s degree in psychology (he would also later earn a master’s degree) and decided that he wanted to pursue a career in kiruv.

“But before dedicating ourselves to outreach, my wife Esther and I felt that we needed a bit more, so we moved to Yerushalayim, to the then-new neighborhood of Har Nof.”

After two more years of in-depth learning, the Steinhardts accepted their first position in the Dallas outreach kollel.

It was a rewarding and fulfilling period for the growing family.

Rabbi David Leibtag, the then-principal of Dallas’s Akiba Academy, saw potential in the kollel fellow.

“You know,” he told young Rabbi Steinhardt, “you have a master’s in psychology and the Torah background to apply what you’ve learned to our students. I’d like to make you guidance counselor at the school.”

Like Dr. Joseph Kaminetsky a generation earlier, Michael Steinhardt had the yeshivah perspective, but also the credibility that came along with his degree.

“What I discovered changed my life. I realized that it’s not enough to pinpoint an area where a student is struggling and try to correct it. As a guidance counselor, I was able to see the bigger picture. If a kid isn’t focusing in class, but his parents are throwing pots at each other every night at home, then he doesn’t have a behavioral problem, he’s anxious that they’re going to get divorced. So if you treat what you perceive as a conduct issue but don’t deal with the real issue, you’ve cheated the child.”

“I knew what I wanted to do, but the only question was how to do it.”

Chizuk for Every Kollel Guy

The clarity of hindsight: the one-time founding member of the Pediatric Neuroscience Institute and lecturer at Hackensack University Medical Center, a doctor with a months-long waiting list, one of the leading figures in his chosen field, shakes his head in wonder.

“My story is chizuk for every kollel guy with a bunch of little children who wonders what he’s going to do.”

With three children, the Steinhardts made a decision: he would go back to school and she would work to support the family.

Neuropsychology was a relatively new field at the time, the early 1990s, and it was very difficult to get into a clinical program. “With great siyata d’Shmaya, we managed to find a great program at Nova Southeastern University. I managed to get some coursework at Miami’s Jackson Memorial Hospital, one of the first hospitals in the nation to have a team of psychologists integrated into the mainstream medical staff. At the time, this was a ‘chiddush’ — to accept that psychology had a role in conventional healing.”

Dr. Steinhardt was amazed at the importance of brain-behavior relationships and a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment to assist in diagnosis.

“It was a very progressive field at the time, but it was growing quickly. It’s said that when Einstein was given an hour to solve a problem, he would spend 55 minutes quantifying the nature of the problem and breaking it down to its parts, and then the final five minutes solving it. By understanding the problem, you start seeing common underlying patterns and barriers start falling. That’s what we were doing here.”

After completing the program, the doctor applied for his internship. It was time to move again, this time back home. He joined the staff at Long Island’s North Shore University Hospital, working under Dr. Barbara Wilson, one of the founders of pediatric neuropsychology.

“It was very much an old-boys network and it wasn’t easy to break in, but I had a mentor.”

Dr. Steinhardt stands up to remove something from the shelf behind him. He hands me an old copy of Mishpacha magazine, a picture of Dr. David Pelcovitz, a professor of clinical psychology at New York University and Yeshiva University, on its cover. “He helped tremendously, easing me in and guiding me every step of the way.”

He Hasn’t Been Treated At All

The Steinhardts settled in Monsey in 1995. “It had an out-of-town feel, which gave us the best of both worlds, proximity to the city and the quiet we’d gotten used to.” The doctor put in five long days each week at the hospital, leaving Monsey in the pre-dawn darkness to beat traffic.

Sundays were free, but he made another decision. It was time to use his newfound expertise and apply it to his own community.

“I started seeing patients one day a week, in Suffern, and hearing the stories, the ADHD and learning disabilities. I started working with people, trying to make them understand that there’s a bigger picture.”

Soon enough his reputation grew, and in 2008, Dr. Michael Steinhardt left his full-time responsibilities at Hackensack University Medical Center and opened his practice in Montvale, New Jersey, just minutes from Monsey. In short order, his number was on speed-dial of yeshivah principals and school psychologists, those seeking solutions, rather than labels like ADHD, ODD, or OCD.

“A diagnosis is great, and sometimes medication is the best solution, but I think people appreciate that we work without a prescription pad. That means we’re ready to sit back and really examine the data, from all angles.”

Along with a long wait, appointments come with a high price tag. The doctor explains the cost. “When a child is brought here, we don’t take short-cuts. We examine all core underlying areas of cognitive and emotional functioning to truly understand each child we evaluate. It usually takes a few sessions, so that we make sure we’re examining him. If he’s tired or cranky, it won’t work, so it takes several hours over a few sessions for the actual exam. We try to make each child comfortable and relaxed so he or she can just be. Then, after the evaluation is completed, it takes hours of poring over the information and finding patterns, trying to solve the puzzle.”

Conversations with menahelim and educators provide insight into what it is, exactly, that Dr. Steinhardt does. When a child is not performing or developing as expected, the first red flags appear. The child may be struggling with his thinking or processing skills (having difficulty staying focused in class, learning and remembering material being taught), or be experiencing behavioral or social difficulty (acting in an impulsive or defiant manner). When these difficulties do not interfere with the child’s overall ability to navigate his daily routine, the parent or teacher may do nothing more than make minor changes to improve the child’s adjustment. However, when the child’s challenges are consistently and significantly interfering with his day-to-day functioning, it becomes increasingly clear that something more need be done.

That’s where the neuropsychological evaluation comes in. The process is fairly simple, not unlike a visit to a pediatrician in which a parent describes the symptoms. In the opening interview, the child’s parents describe the problems they see their child exhibiting, and share the concerns expressed by teachers or other professionals working with the child. A review of the child’s developmental, medical, and educational history, as well as previous evaluations and interventions, is also conducted at this point.

Following the interview, the evaluation with the child begins. Tasks that have been identified as key underlying skills necessary for a child’s success are administered in a structured but gentle and interactive manner, so that the child is able to demonstrate what comes easily to him, and what type of activities he finds challenging. Since these tasks have been well researched and administered to many children across each age group, and normative data has been gathered, the child’s pattern of performance is analyzed to determine whether his abilities are developmentally appropriate, and to conceptualize the child’s difficulties. Behavioral, social, and emotional functioning is assessed somewhat differently, utilizing parent and teacher rating scales, behavioral observation, projective measures of personality functioning, and a thorough clinical interview. The process usually takes place over the course of two to three sessions, a couple of hours per session.

“This is important. Children typically enjoy the evaluation process, as they often find many of the tasks interesting, interactive, and challenging. Positive reinforcement is routinely used to encourage each child to do his or her best. We try to make it pleasant as possible.”

Following the evaluation, a meeting is set up with the parents to discuss the results of the evaluation and to come to a clearer understanding of the nature of their child’s difficulties. Based on these findings, Dr. Steinhardt provides evidence-based treatment recommendations. The recommendations may involve specific educational interventions, emotional support, medication consultation, parent training, and/or social skills training, to name a few. Results of the evaluation and recommendations are subsequently provided in a detailed written report. This process, while extensive, has proven to be extremely effective in identifying the underlying causes of a child’s difficulties in an objective, unbiased manner, and sets the stage for a focused action plan to help each child based upon his unique set of strengths and challenges.

“I am not well-versed enough in the field to be able to provide educated analysis,” says Rabbi Yosef Mashinsky, menahel of Monsey’s highly-regarded Beis Dovid cheder, “so I’ll simply say that Dr. Steinhardt, with his understanding of the yeshivah system in its many shades and colors, lends a unique insight that other professionals do not bring to the table. His meticulousness, patience, and general expertise allow him to identify the dysfunctions, disorders or challenges faced by a child, and provide solutions. You can’t argue with his success.”

The practice draws patients from across the spectrum: from Modern Orthodox schools to chassidishe chadarim. Is there a different approach to treating products of different kehillos?

“The mindset is certainly different. Among the chassidim, I find Belz to be more progressive in terms of accepting psychology as legitimate, and they are always willing to work with us, but the entire frum community has come a long way. I recently lectured to a group of Satmar educators during the summer and they are open to hearing as well.”

The Curse of Panic

With new information also comes a spike in conditions being treated in our community.

“Anyone who says that our system creates OCD or ADHD, with the rigorous and exacting standards and schedules, is anti-Torah. Torah living doesn’t do that. There is certainly a genetic component to it — many of these conditions are hereditary — and the fact is, all this awareness brings the blessings of allowing people to accept themselves despite whatever condition they may have.”

A humorous story. “A popular frum psychologist was at a hotel and a frum couple stopped to ask if they could speak with him. He sat down with them and asked, ‘Nu, which one of you has OCD?’ They were amazed. He understands that many people are walking around carrying baggage, waiting for the right moment and right person to talk to.”

Along with the blessing of awareness comes the curse of panic, however. “Preying on the vulnerabilities of parents isn’t right.”

He reaches into his drawer and pulls out a thick matte-paper circular, the kind popular in frum neighborhoods: bursting with ads for groceries, baby furniture, clothing sales, some classifieds and mazel tov announcements. He holds it up like an auctioneer.

“Do you know what happens in these pages towards the end of summer, the beginning of the new school year?”

He starts to read from various pages. “Give your child a new chance… The secret herbal ingredient to your child’s success… Learn how your child’s diet can solve his problems… Brain-management techniques to unlock his mind and potential… Hypnotize your child to the top of the class…”

He speaks grimly. “Good parents run in circles wasting time, money and energy chasing solutions that will leave them frustrated.”

Stories Aren’t Research

But who’s to say what’s legitimate and what’s not, I challenge him. Perhaps purveyors of these treatments would view neuroscience with the same skepticism.

He welcomes the question. “Very simple. I’ll tell you how you can know what is a valid course of treatment and what isn’t. There are a few guidelines.

“First off, when all the evidence is anecdotal, and not research-based, that treatment approach is suspect.”

He indicates one of the ads.

“This changed my life —Heshy G, Brooklyn.”

“Everyone thought our son was ADD but now we know it’s just a vision problem, once we corrected it everything is great. —Chaya P, Lakewood.”

“This proves nothing. Stories aren’t research.”

Another guideline is that cure-alls are usually cure-nothings.

“When the same remedy is said to heal a wide range of conditions, from depression to athlete’s foot, then it likely isn’t very effective.”

Unchanged methodology over time is also a danger sign.

“Science and medicine keep evolving. New discoveries are made every month and new studies disprove things that were previously taken for granted. But with these quack treatments, there’s no way to argue, no findings that can make them rethink their approach, so things stay the same year after year.”

Lastly, these revolutionary new treatments are often based on the dogma of a single charismatic leader.

The doctor minces no words. “It’s essentially the difference between Yiddishkeit and avodah zarah. Truth sells itself while alternative ideas need a charming salesman. Most of these breakthrough ideas are based on the charisma of a single guru.”

He shrugs. “Look, I have no negius, I don’t advocate for any course of treatment and I don’t write prescriptions. I just want the kids to be successful.”

A Wise Menahel

The panic of which he speaks affects most parents, to a degree: people sometimes wonder if “normal” parenting can work anymore, in 2014.

“Good parenting can be enough if parents have the breadth to give over a feeling of success to their child, even if it’s in a nonacademic area. School can be torture for certain kids and, especially for boys, learning is crucial to self-image. Kids facing difficulties are automatically at risk of seeing themselves as failures, so parents have to be able to transmit pride in whatever area the child shines. It isn’t as easy it sounds because kids know when parents are being genuine and when they’re just parroting ‘You’re amazing’ because they think they have to say it.”

It’s not only parents who have difficulty in finding a balance between normalcy and alarm: it’s a challenge for schools as well. “I would think that schools should have someone on staff who understands the fine line between little problems and big problems. A wise menahel goes a long way.”

The schools are doing a heroic job, the doctor maintains, but at the same time, vigilant parenting is necessary.

He gives an example, something he heard from a teenager in his neighborhood.

“She told me that she was a counselor at a day camp, and the camp administration gave the staff very clear instructions: at the end of the day, they were to tell the parents how wonderful their children had been. It made no difference if the child in question was a terror: they were to lay it on thick. Why? Because a day camp is a business, and their goal is to have happy parents. Telling parents nice things about their kids makes them happy — they’re really not interested in hearing complaints — and then they like the camp and recommend it to others.”

The doctor pauses for a moment. “Sounds like a conspiracy theory, right? But really, it’s simple. Everyone is too busy to deal with issues, so let’s keep cheering. Now, it’s one thing in a day camp, but it can happen in a school, too, this unwritten contract between student and teacher to keep things quiet, not to raise concerns. It’s just too complicated for the teacher. That’s when parents have to trust their instincts to see what’s PR by the school and what’s an accurate report.”

Comes a Blessing

Dr. Steinhardt walks me out of his office. Night has fallen, and, other than the cleaning staff, we are the last people in the medical building. As our footsteps echo through the darkened halls, he ruminates. “It’s a hard time to raise children, but along with the challenge comes blessing, an acceptance of our limitations.

“I had a couple here from New Square, and it was clear that this was a situation where the child would benefit from medication. The father started shouting at me, ‘My son isn’t going on any medication, he’s normal.’ The next day, he went into the Skverer Rebbe and told him what happened. The Rebbe asked him, “Why are you angry at Ritalin? Why aren’t you grateful? It’s helped so many children.’ ”

We step into the nearly vacant parking lot and I ask the doctor if this is a regular occurrence, that he’s the last to leave the office building, working longer hours than anyone else. Dr. Steinhardt’s features are briefly illuminated by headlights from a passing car.

“My grandfather worked hard, building schools. I try to follow his example, working hard to build people.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 542)

Oops! We could not locate your form.