Comeback Mission

Rabbi Uri Zohar journeyed from brazen celeb to sincere seeker — and invited the entire country to join the ride

Photos: Eli Cobin, Mishpacha archives

A few hours after we left the tiny machsan on Rechov Zichron Yaakov that Rabbi Uri Zohar had called home for the last decade, we got a phone call.

On the line was Uri Zohar himself.

“I thought about it again, and I’m asking you not to publish the interview,” he requested. “I really try to avoid media,” he said, “and I’m sorry for the inconvenience, but I’d appreciate if you could honor my request.”

We shelved the interview (knowing from experience that we were taking a risk), missing a “scoop” perhaps, but happy that we were helping this giant of a man keep to his resolution and continue living in the shadows. Little did we know that just a few weeks later, it would become his eulogy.

Former actor and director Uri Zohar, icon of the secular Israeli entertainment industry in the 1960s and early ’70s until he turned his back on it all to study Torah, passed away last week at age 86, after four decades of creating his own Har Sinai.

Half of Rabbi Uri Zohar’s life was spent as Israel’s most famous cultural icon, and then he spent the second half of his life trying to escape that same public adulation. At a certain point, after he became a baal teshuvah, he even tried to purchase the broadcast rights for all the movies he had acted in. But he wasn’t able to do it, and to this day, he’s remained a sort of cult figure in the Israeli entertainment world.

“Kapparas avonos,” he would say when someone spoke to him about his earlier life.

The Tel Aviv–born Zohar was known for his outsized personality, sharp wit (he was always a bit of an intellectual, having earned a university degree in philosophy), shoulder-length wavy hair, and most of all for his comic sketches and 1960s “bourekas” films — slapstick movies that poked fun at nearly everything sacred in the fledgling state and became Israeli culture classics. While other films aimed at a new genre of cynical viewers were mostly commercial failures, Uri Zohar was able to astutely analyze the economic situation of the Israeli cinema.

When Zohar disappeared from Israel’s pop culture scene in the late 1970s to learn Torah and eventually become a chareidi rabbi in Jerusalem, it was a shocking move. But the public’s loss was the Torah world’s gain. Uri Zohar switched venues, but he was still larger than life.

He was the most tangible example of the words of Chazal, “In the place where baalei teshuvah stand, complete tzaddikim cannot stand.” And he was not only a baal teshuvah, he was also a tzaddik. He eschewed materialism to an extreme, having dedicated his days and nights to one thing: Torah, Torah, and more Torah — yet his essential personality continued to sparkle, schlepping along unaffiliated Jews on his journey.

Although he had a no-interview policy, Rabbi Uri Zohar agreed to a visit from Mishpacha’s Aryeh Ehrlich and Yisrael Groweiss in the tiny machsan he called home. Who would have thought it would be his last time on record?

Real Riches

We’re not easily shocked, but we were pretty surprised as we walked into his most recent dwelling. The undisputed idol of Israeli culture in decades past, the man who once lived in a massive villa on a huge seaside estate in Yaffo, hosting elaborate, place-to-be parties for the who’s who of Tel Aviv, and who later moved to a simple, seforim-lined apartment on Rechov Panim Meiros in the Mattersdorf section of Jerusalem, was now living with his wife, Rabbanit Eliya tbl”ch — who nearly divorced him in the 1970s before deciding to embark with him on his spiritual journey — in a tiny 25-square-meter converted storeroom-studio. From morning to night, he sat on a piece of furniture that was half-bed and half-couch, spending his waking hours learning with multiple chavrusas.

“Reb Uri,” we asked, “why live under such Spartan conditions? Why did you choose such a radically modest life?”

He just smiled that famous mischievous smile and said: “I don’t know why you call this a Spartan life. I live in a palace, and feel like the wealthiest man in the world. In a big house, you need a compass and a map to get around, and you have to keep running from room to room. In my castle, the dining room and kitchen are one and the same, and the bedroom is near the front door. This is very comfortable, five-star — and everything within arm’s reach. Why would I need more than this? Besides, I’m preparing for the day I reach my grave. There, it will be even smaller and more crowded. Now I’m at a stopover.”

His face glowed, as if he were sitting at the top of the world and living a life of luxury. He sat on an ancient couch that served him when he learned straight from vasikin until chatzos at night, and for a short nap in between (the adjacent room has proper beds). There was also a small counter, refrigerator, and a stand of shelves for seforim.

There were also lots of little notes all around, with the pasuk of Shivisi.

“It’s not frumkeit,” he chuckled. “It’s the first passage in Shulchan Aruch. Because you can’t compare a person’s movement when he is in front of HaKadosh Baruch Hu. It’s a clear Mishnah Berurah.”

He had many such little notes — in his pants pocket, for instance, so he’d always pull one out when he was looking for something,

This little chamber is the corridor in which Reb Uri spent the last decade preparing himself for Olam Haba. There’s a sense of Gan Eden here — the disdain for everything worldly almost screams from every corner.

“I’m happy,” Rav Uri declared. He knew exactly what the world had to offer.

The whole subject of interviews and media chatter was very hard for him. Not because he was ashamed or wanted to cover his past — he talked about it openly — but because of the headache and the bittul Torah and disruption of his sedorim.

“You know, I was 40 years old the first time I saw a talmid chacham,” he said. “So I had no choice. All of Har Sinai fell on top of my head.”

Yet decades after he left the opulence and glitz of stardom for the austere life of Torah and the spirit, Rabbi Uri Zohar went back to the studio once, eight years ago, for what he called the most ambitious media project of his life.

Not that the studio had been foreign territory all those years — even after he bowed out of the public eye and abandoned his persona as Israel’s top actor-comedian-entertainer, he’d been featured in close to a hundred kiruv and Torah shows, many of them for the Hidabroot Jewish cable channel. But at close to 80, he took a brief break from his intensive daily learning schedule to create a series of shows aimed at opening the door of the Torah world to those who have absolutely no idea what’s inside.

“I guess this is what you call a comeback,” he quipped at the time to Mishpacha’s Menachem Pines, whom he let into the studio to watch the shoots.

The Parasites is the title he chose for his film series — and maybe that’s the term that brought him back to the place where he thought he’d never return.

“If they’re calling those who learn Torah ‘parasites,’ ” he explained at the time, “it’s because they have no concept of what Torah learning is. They assume you only study something in order to achieve a certain goal. Why, they wonder, would people want to sit and learn all day long without any apparent purpose? I remember that that was the question when I came to Yerushalayim. My wife and I had already become baalei teshuvah — we already knew that there is a Creator, but what more did we need to do? It took us a while to realize that Torah is not just a subject, not something that we study for some ulterior purpose. The Jewish People always knew this, throughout all the generations over thousands of years, but in the past 200 years, we somehow lost this knowledge.

“I was in Sao Paulo, Brazil, for Lev L’achim. We came to a religious shul, and it looked like a boardwalk on a hot summer day. I asked myself what I was doing there, whom I was going to talk to. But then came Krias HaTorah, and they lifted the sefer Torah while everyone cried out, ‘V’zot haTorah!’ All the men and women were standing, blowing kisses into the air and crying, despite their outward appearances. The inner essence of every Jew was there. Despite the trappings of Olam Hazeh, they understood how our very essence is bound to the Torah.”

There was one thing that would make him close his seforim and go back public: if doing so would inspire another Jew. That’s why organizations like Lev L’achim were so close to his heart, and why the Israeli story was so painful to him. In his book, My Friends, We Were Robbed (Lo Natnu Chance), that’s the cry he extended to each one of us.

“There are hundreds of thousands of our brothers. They are miskeinim, unfortunate people,” he would say. “No one gave them a chance. No one gave them an opportunity to get to know their glorious past. No one taught them the basics of Yiddishkeit. And now, we have a chance, whether through a donation or with actions, to do kiruv. These are our brothers. Who will take care of them if we don’t?”

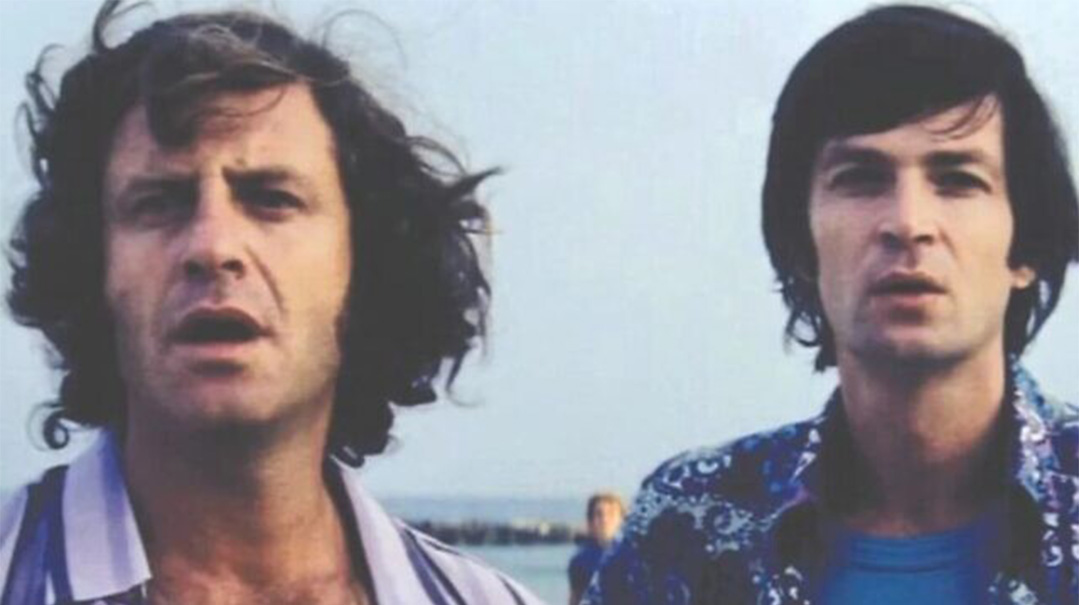

Uri Zohar in other days, with his longtime sidekick, best friend, and eventual mechutan Arik Einstein. “Saba Uri has a beard long enough for both of us”

They Were Empty

Mention kiruv king Uri Zohar, and people are curious about two things: how he made the transition from celebrity to scholar, and his relationship with his former sidekick, double mechutan and iconic Israeli singer Arik Einstein, who passed away in 2013.

“Arik and I grew up in the same neighborhood,” Reb Uri said. “We went to the same elementary school, and the same high school, we were in Shomer Hatza’ir together — we were really inseparable. And I never heard him offend another person, even once. He was really a prince.”

Did he ever try to get his best friend to do teshuvah, when he was instrumental in bringing back so many others from the entertainment world?

“I tried a bit, it didn’t go,” he said.

“He did teshuvah, he learns Torah now, and his wife and children with him. A year has passed; nothing has happened. It’s the same tune and the same words. But the heart wants much more, to tell a different story. Yet you have left me, my friend…”

These are the lyrics to a song Arik Einstein wrote about his best friend after Reb Uri’s return to Yiddishkeit. Yet although it seemed that Reb Uri did leave for a place far away, the two men’s lives remained intertwined. Einstein’s ex-wife and children were chozer b’teshuvah, and his two daughters married two sons of Uri Zohar. They have 18 mutual chareidi grandchildren. So although Einstein never made the leap, his children and grandchildren kept him connected.

Once, when his young grandson came to visit, the child asked, “Saba, how come you don’t have a beard like Saba Uri?”

Arik smiled and said, “Saba Uri has a beard long enough for both of us.”

Uri Zohar never looked back, although he was occasionally forced to make his own reckonings.

“At Arik’s levayah, I met some old friends from the industry whom I hadn’t seen in years,” he said. “They were once on top of the world, but today no one remembers them — the younger generation has taken their place. Suddenly, they can’t get that external jolt of satisfaction that comes with prestige and ratings. Everything is gone, and what does that leave them with? I was there standing with the best of the industry, and where were they? Empty, thirsting for something that they could no longer get, not even understanding what they were lacking.”

Still, did he miss it at first?

“I’ll be honest,” answered Reb Uri. “After three or four years, when I was already in Yerushalayim and had taken on mitzvah observance, I took stock. ‘Maybe I’m just fooling myself? I keep telling myself that things are good for me now, but maybe I’m really longing to return to that place?’ So I decided to test out my theory and called my old friend and sometime co-star Avigdor Tzabari [of “Hatzrif shel Avigdor” fame, Avigdor’s famous celebrity hangout hut overlooking the Tel Aviv beach].

“So we arranged to meet, and all of our friends came. There were all sorts of substances there that are supposed to make a person happy, but after five minutes, I couldn’t take it. Over and over again, they were talking about the same things — nothing had changed, nothing had moved forward. It was still about soccer, Hapoel Tel Aviv, politics, what this person or that person was doing, more jokes and empty laughter. It was all so pointless. And suddenly I knew that I was living a life with a purpose, that I myself — not my bank account — was growing. My house might have shrunk, but I was expanding. Today, referring to that secular culture, my wife calls us spiritual Holocaust survivors.”

Still, Reb Uri was saying Kaddish for all those souls who thought they were at the top of the world yet essentially faded into oblivion.

“Shmuel ben Moshe Kraus, Yoram ben Moshe Kaniuk, Aryeh Leib ben Yaakov Einstein…” he utters.

Shmulik Kraus, an actor and pop-rock singer who served jail time for illegal gun possession and had a song about smoking hashish banned; Yoram Kaniuk, a popular Israeli writer and theater critic who married a Christian woman, renounced his Judaism and petitioned the Interior Ministry to change his religious status from “Jewish” to “No Religion”; and of course, Arik Einstein. His old friends went to the grave with nary a Jewish connection, other than the Kaddish Reb Uri was makpid to say for them. Was there a Jew today who cared about the soul of Yoram Kaniuk, an avowed apostate, besides Reb Uri?

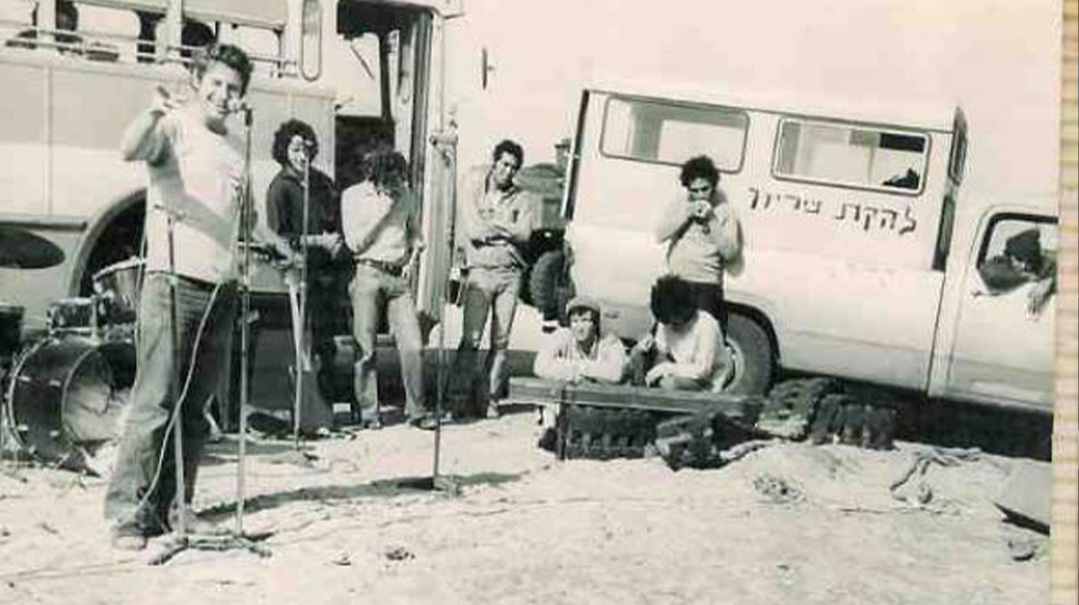

Uri Zohar at the microphone with his entertainment troupe, performing for soldiers during the Yom Kippur War

A Cooler Gehinnom

During the ’60s and ’70s, the young Israeli culture — movies, theater, songs, and comedy — was largely dominated by a charismatic group of sabras. And in a certain sense, to this day, Israeli culture still culls from the way they styled it forty and fifty years ago.

The state was small then, with one media channel and two main newspapers. The entire country knew these stars and their nicknames. There were Arik and Pupik and Pashanel, and their chief: Uri Zohar.

His story was one of white Ashkenazim, the child of Polish immigrants who changed their name from Dzadak to Zohar. He took the regular sabra route of studies and army, and then someone noticed his exceptional talent. He was sent to the military choir, which eventually became a famous civilian troupe.

Charismatic Uri was indeed zoher, he shone. He could go on stage without a script and have his audiences rolling with laughter.

“I look back,” he admitted so many decades later, “and I don’t understand how hard we worked. We had no day and no night. We were like a machine churning out hits. We kept writing, performing, filming, and composing. We aired broadcasts and talked. It wasn’t for parnassah, because we didn’t earn too much — it was for a much deeper need. I didn’t yet know then how to put into words the thirst of a Jewish soul.”

Yet there was no special performance, no lights or shattering glass. He was at the height of his career at the time and lacked for nothing. He was even raising a family. He had no reason to make a change.

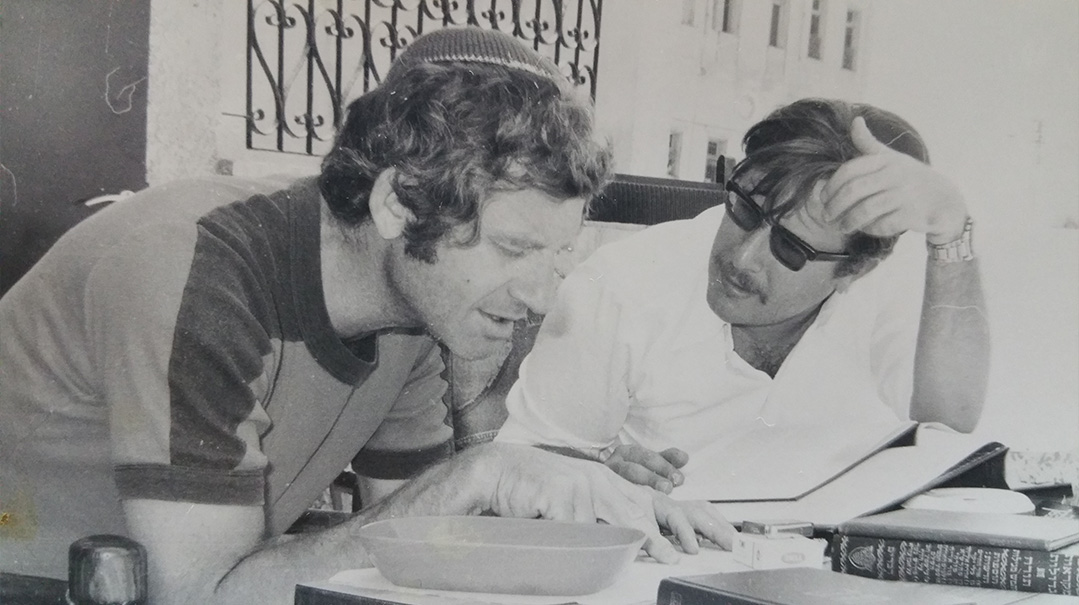

The turnabout happened among a few of his friends. One was Reb Mordechai (Pupick) Arnon, who left the group and fled to a beis medrash in Jerusalem. Yet with all due respect to religious friends, Uri never thought that they had any serious rationalistic position. And then came a random encounter: During a visit to Jerusalem to celebrate a family simchah with one of his newly religious friends, he met the figure who was destined to change his life.

“Rav Yitzchak Shlomo Zilberman [founder of the “Zilberman” education system, and the talmid chacham responsible for Uri Zohar’s Jewish reawakening, referred to as “the Yerushalmi” in his autobiography, Waking Up Jewish —Ed.] lived in a small Jerusalem apartment. He had 18 children. Lots of sons and lots of daughters. Everything that in my eyes was perceived as majorly depressing,” Reb Uri remembered. “He looked at me challengingly and said something that seemed so off: ‘I am the happiest person in the world.’ And it seemed to me then like a good joke.

“When we continued speaking, Rav Zilberman asked me what would happen if he proved to me that there is a Leader to the world and that the holy Torah is a Toras Emes.

“At this point I literally laughed. ‘Tell me,’ I asked him, ‘Do you understand the meaning of the word “proof”? You’re talking about faith, and faith is not something you can prove.’

“But Rav Zilberman insisted. Yes, he said, he completely understood the meaning of the world. And he had a wager. ‘And if I prove to you that Torah is true? Will you observe it?’ I was fair enough to say that indeed, yes. I am a person who operates according to rationalism and the truth, and if someone could prove to me that my path in life was a mistake, I would be compelled to change it.

“At that point, I was very sure of myself. After all, I was an educated person, I had attended university and studied philosophy, literature, and history, and the possibility that some ‘black’ rabbi would prove to me something I considered irrational blind faith didn’t seem like a big risk.

“The first surprise was that this ‘frummie’ was very balanced. He spoke several languages. He had come from a Yekkishe family in Berlin and had an amazing scope of education and knowledge. With relative ease, I could, in my imagination, remove his peyos and his garb, and see a progressive person who could have challenged me on any subject in the world. And what was the most amazing was that this ‘progressive’ was so pious and was not ready to deviate one iota from even the minutest of mitzvos. And all because of his recognition that obligated him.”

Until his final day, Rav Uri did not forget that first sharp blow to his consciousness.

Rav Zilberman faced him, standing and presented what he called the “paradox of the mitzvos.”

“Let’s say you’re right and someone made up Judaism,” Rav Zilberman said. “This person wants to convey to his believers social, ethical, humane values. So explain to me how this person could establish a religion that has a law as follows: An elderly Jew is writing a letter to his grandson, when suddenly, two other Jews come in and shout at him, ‘Mister, do you know that today is Shabbos? You’re not allowed to write. If you continue, you’ll be stoned.’

“Or, a grandmother is knitting a sweater for her granddaughter, and two Jews come in and warn her, ‘Bobbe, s’iz Shabbos. If you make two more stitches, they’ll kill you.’

“So this must be a nation of crazies, passing on these laws from father to son for thousands of years. Don’t you think it’s a nation of total crazies?!”

“Sure they are!” Uri exclaimed.

But then the Rav continued, naming a list of those famous “crazies,” some of whom Uri recognized: the Rambam, the Ramban, Rashi — the best minds in humankind made the effort to convey these “insane” laws for thousands of years.

“In short,” Rav Zilberman said, “such a historic process could not have been a human creation, it had to be the word of Hashem.

“I didn’t have an answer to that,” Reb Uri remembered. “The words penetrated me like snake’s venom.”

The entertainer from Tel Aviv promised to think about it and come back with answers.

“We met again a few weeks later,” he related. “I brought all my material with me. It turned out that he already knew all my nonsensical research. He knew all about evolution and refuted it easily. Today, they make entire seminars in Arachim about this, but then, it all just got stuck in my throat. I realized I was in trouble, that that I needed to fulfill my part of the deal. I felt all of the Torah falling on my head. Six hundred thirteen commandments that I had no interest in observing.”

He returned home and continued learning. “I made a decision to try to learn the Tanach once, as if it were really true, and not as I had always viewed it — a collection of historical myths and legends. The truth is that I had no intention of getting close to the Torah, but I realized that in order to try and examine its truth, I had to abandon my frozen, unchanging view of the Torah, and to give a chance to the premise that it is true.

“I opened the Chumash — I remember the day, the hour and where I was. I was sprawled on my bed, as I began to read the first pasuk. I read slowly. I read about the Creation of the world. Then, when I got to the second pasuk, to ‘Vayehi ohr,’ and I stopped. What kind of strange concept was ‘light’ when there was no source of light yet? It did not say ‘Vayehi shemesh,’ as the sun was created only on the fourth day. So which light is being referred to here? If someone had really made up the Torah, he could not have made such a mistake right at the beginning.”

Within a short time, he realized the complex situation he was in. He took the note with Rav Zilberman’s number and dialed with a trembling finger. He had only one question. “Let’s say I agree to keep mitzvos. I don’t have to go with the strictest version. I don’t want to be in the front row, I just want to cool down my Gehinnom a bit, so it won’t burn on my back. So what’s the minimum, what is the most important for me to keep?”

Rav Zilberman’s answer surprised him. “He told me Shacharis, without too many additions, should take about ten minutes a day. I needed to eat kosher, at least Rabbanut. Make brachos before food. Shabbos, you don’t have to do anything. Get up in the morning, daven a short davening, eat something kosher and then go to sleep until Shabbos is over. Nothing too complicated.”

Starting to learn Torah after losing a bet to Rav Yitzchak Shlomo Zilberman; years later, he’s still the voice, but to a different crowd

Serious Business

When Uri Zohar first appeared in a kippah and tzitzis on a television game show he was hosting, everyone thought it was a joke. For a man who could bring down an entire theater with the slightest gesture, anything was possible.

“Do I look good?” he asked, referring to the kippah, and the audience roared with laughter.

But it soon became clear that the question had been entirely serious. Uri Zohar was no longer the man they thought they knew. The staunchly secular, irreverent Israeli actor who brought all the world’s desires to the screen was no longer with them. They even accused him of treason.

By the time he was working on his final film, Hatzilu et Hamatzil, in 1975, he was already wearing a kippah, keeping Shabbos, and putting on tefillin every day; but at the studio, people were waiting for him.

“I just need to finish this project, and then I’ll learn Torah,” he told Rav Zilberman.

“What do you need to finish it for?” the Rav asked.

“I worked on it for a year. Should I let all that work go to waste?” Uri responded.

But there were still four months of shooting left, and another few months of editing. Should he really waste another half a year?

The contracts were already signed, and it was impossible to back out. Breaking the contract would cost him half a million lira. But deep within himself, he wondered what he was doing there, with those people. The film was finally completed, and its first screening, amid intense media attention, took place on an Erev Shabbos. Reb Uri waited outside the theater where his own film was being screened, and after the audience and media crews had entered, he surreptitiously stepped inside as well. But not more than five minutes passed, and he was back outside on the street. He never even bothered to watch his own movie.

His wife, though, was not exactly on board, was not willing to keep even the minimal requirements, and had filed for divorce. The night before they were about to get divorced, Uri went to sleep, feeling a crushing weight on his chest — he really didn’t want to break up his family, but what could he do? He went downstairs and saw her reading.

She looked up and said, “Okay, I’ll keep the minimum so that we can stay married.”

She showed him the book she was reading: It was the Rambam. “I don’t understand any of it,” she said, “but I know it must be serious business.”

“I was learning then about the concept of bitachon in Hashem,” he related. “I reached the conclusion that it obligated me as well. Just then, I had done an advertisement for Tadiran. I earned 20,000 liras, a nice sum in those days. I told myself, now I have money for quite a while. I can move to Jerusalem until the money’s used up.

“Baruch Hashem,” he said, “It’s been 45 years and the money hasn’t finished yet… True, it’s not always easy. But Hashem helps. There’s no minus in the bank.

“I still get royalties from past projects. I once went to Dayan Fischer and asked him if I was allowed to benefit from that money, and he said, ‘Why not? Let them see that not only crazy people are chozer b’teshuvah…’ ”

It Obligates Us

All Uri Zohar wanted to do was to retreat into his learning and serve Hashem. But then he was presented with a request by gedolei hador. Rav Shach summoned him, gave him the directive to stop thinking only of himself, but to go out there and bring in more neshamos.

“I remember the first show. There were huge signs — ‘Uri Zohar is returning to the stage.’ They took me to Holon. On the way I saw there was terrible traffic. I thought that there must be a major sports event going on. Then I realized that they were all coming for me.

“A venue that was designed for 500 was packed with 2,000 people. It was so crowded that they called the police. Suddenly I realized the tremendous thirst there is in our time, the generation of Ikvesa d’Meshicha, to hear the Word of Hashem. These were people who knew me from before, but they all knew that this time, they wouldn’t be hearing jokes, only words of Torah. And they came anyway.

“That night, there were thousands of forms filled out by Jews who wanted to come closer. One wanted a chavrusa, the other wanted guidance for a bar mitzvah. And the more I traveled around the country, the more forms we got. We got to 40,000 forms, and then the question was: How do we handle all this? That is what led to the establishment of Lev L’achim. We realized that we had to establish a center in each city to deal with the requests from that city. That’s how Lev L’achim came to be.

“Now there is a very intensive process of clarification between good and bad,” he continued. “We see on the one hand the darkness mounting. There are difficulties. On the other hand, thousands upon thousands of Jews are yearning for a bit of light of Torah and holiness. And that obligates us.

“Rashi explains that the last three words of the Torah, ‘L’einei kol Yisrael,’ refer to the breaking of the Luchos. But how can the Torah, summing up Moshe’s legacy, end with that? Because when Moshe broke the Luchos, Hashem agreed, since through those broken shards, there is even more light and more possibility for every Jew to draw closer.”

Last week, while Am Yisrael was preparing to receive the Torah on Shavuos, Rabbi Uri Zohar, who spent half his life making people laugh and the other half bringing people closer to the Last Laugh, who gave us all an idea of the proportion of the dissonance between the holy and the mundane, between the transient and the eternal, between temporary and permanent — left This World to receive the Torah in the Yeshivah shel Maalah.

His mechutan, Arik Einstein, wrote after Reb Uri was chozer b’teshuvah, “Halachta li chaver — you have left me, my friend.” But just like Reb Uri never really left him, perhaps he’s never really left us either.

When he was a performing superstar, he would always open every show with the words, “Ani yafeh hayom — am I beautiful today?”

Today, all of Am Yisrael can say, “You are yafeh, Rabbi Uri Zohar, you are beautiful, and you shine.”

For an Audience of One

By Rabbi Doniel Baron

The world abounds with aging celebrities whose most defining virtues are some identity from their distant past. And while they may appear as crumpled, lonely souls fixated in the past, tucked away in a nursing home, they assure anyone who will listen how important they once were.

Rabbi Uri Zohar was no such faded star. Well into his eighties, he continued to inspire and lift up all those who encountered him. He was a rare ish emes, a person of truth. And to those who really knew him, his past life in the limelight of secular Israeli society was a mere interesting detail — independent of the adam gadol he was in the present.

Despite his appearances on behalf of Lev L’achim and occasional speaking engagements, Reb Uri spent most of his day learning and intentionally kept a low prolife. Like many in the yeshivah world, I only had some vague idea of who Rabbi Uri Zohar was when Rabbi Yonoson Rosenblum asked me if I’d be interested in translating Reb Uri’s book on raising children (published in English as Breakthrough: How to Reach Our Struggling Kids.)

I confess that initially I didn’t understand why people would regard Reb Uri as an authority on chinuch. But that quickly changed when I read the book — and it changed even more when I met Reb Uri in person. I discovered that some of his own adolescent children had struggled with Yiddishkeit. And his boundless love, belief in what they could become, and refusal to be distracted by questions of blame, bore fruit. Ultimately, they all followed their parents’ path of avodas Hashem. And anyone who knew Reb Uri could understand why.

Reb Uri viewed the effort to break through to “off the derech” youths as part of Hashem’s master plan. He explained that messages that in one generation resonated with those struggling with their Judaism often fall flat on later generations. As result, there is a need for us to extract a new perspective from within our timeless Torah, ultimately bringing out some facet that resonates in the present. Reb Uri contended that Hashem placed those children with questions in every generation as a means to extract deeper layers in Torah throughout history. As a result, the parents of those children were gifted with the opportunity to find the precise message, together with love necessary to bring them back. In so doing, they would become part of the ongoing revelation of Torah.

That incredible message was liberating. Reb Uri would remind the parents of rebellious children that they were not alone. Avraham had Yishmael, Yitzchak had Eisav, Dovid had Avshalom, and Chizkiyahu had Menashe. Rav Uri’s perspective freed parents from the shackles of guilt, dissipated their anger, and transformed their pain into inspiration. A few years ago, I received a call from a member of a particular chassidic community who revealed that he was struggling with one of his own children. He wanted to let me know that the book changed his life.

Back in 2013, I was sitting at the table in Reb Uri’s extremely humble storage room of an apartment when the phone rang. Reb Uri’s celebrity old friend and twice mechutan had passed away a few days before and a TV network wanted to interview him. He declined, confiding to me that he knew their agenda and didn’t see any good coming from agreeing to meet with them. Reb Uri had no interest in anything that wouldn’t bring kevod Shamayim.

A few years later, I had another idea. My son Shmuel, who was learning in yeshivah a few minutes away, has a keen eye for appreciating true gedolei Torah — even those undercover like Reb Uri. I knew Reb Uri had chavrusas with all types of people, and long considered asking him if he would learn with Shmuel — but for some reason never could bring myself to ask. One day, I, like many others in Israel, received a robocall from Reb Uri in connection with a fundraising campaign. Inspired by the voice, I decided to immediately call the real Reb Uri — and he gladly agreed to learn with Shmuel.

When I first took Shmuel, then 15, to meet an elderly Uri Zohar in that very humble abode, Shmuel wondered what he was doing there. But it took less than five minutes for Shmuel to realize he was in the presence of unique, inspiring, and ageless person. For several months, Shmuel joined Rav Uri’s Pirkei Avos chavrusa with his grandchildren. When I asked my son what about Reb Uri made the greatest impression on him, he remarked that in hindsight, he realized that Rav Uri’s entire life personified Pirkei Avos.

Many in the secular world lamented how Reb Uri had suddenly given up acting when he discovered Torah Judaism. But they were wrong. Instead, in embracing the faith he never knew in his youth, Reb Uri had embarked on his greatest act. He followed the script of an eved Hashem, finally playing the part of Uri Zohar. And the only audience that mattered was an audience of One.

Rabbi Doniel Baron is a Jerusalem-based noted Torah educator and author.

The Best Deal

By Avi Lazar

“I miss you,” I told Reb Uri just two weeks ago as I hung up the phone. Corona had curtailed my trips to Israel the past two years, and with a scheduled trip mid-June, I couldn’t wait to see him once again.

The first time we met was about 20 years ago, when Reb Uri came to my office in IDT on behalf of Lev L’achim. You could tell immediately there was something special about this man as soon as he walked through the door. Maybe it was some leftover charisma from his success in the secular world, or the fact that he came from that background and became a tzaddik, immersed in learning and chesed.

I got involved with Lev L’achim back then, thinking I had what to offer them; I could host parlor meetings, raise money, and donate tzedakah. But what I got, this close relationship with an adam gadol, was so much more than I could have ever anticipated — a relationship I’ll treasure forever.

Upon entering his Rechov Sorotzkin apartment on one visit, I noticed there was a cot in the hallway. I asked a friend what that was all about, and he told me that Reb Uri’s elderly in-laws were living with him. Naturally Reb Uri gave up his master bedroom to them. The cot in the hallway was for his wife, and Reb Uri slept outside on the mirpeset.

The next time I went to visit, I was informed that he’d moved to Rechov Zichron Yaakov, where he lived out the rest of his life.

“You’re not going into a dirah,” warned my friend, “you’re going into a machsan.”

Reb Uri himself used to joke about his humble dwelling. “All the rich people in America have remote controls to do everything. When I sit in my house, I can also control everything without getting up. Adjust the air conditioner? Get a drink from the refrigerator? I can also do that while I’m sitting down.”

When I saw that apartment, I asked Reb Uri, had he fallen on hard times? Did he need help? Was there anything I could do?

He said, “Avi, I’m getting older. I went from a mansion overlooking the Mediterranean Sea to an apartment in Unsdorf and now this machsan on Zichron Yaakov. At this point in my life, I need to prepare for a time when I’ll be in an even tighter space.”

Reb Uri really understood people. He accepted a lot of chumras on himself, but for everyone else, he was as practical as could be. He worked tirelessly on helping kids who were struggling to stay on the derech, and they gravitated toward him. He had this special personality that everyone could relate to. He interfaced with gedolim, and humbled himself to them, but he could also relate to every type, frum and secular alike. He loved every person in Klal Yisrael.

There was a woman who’d been married to a non-Jew in another country and had a child whom she wanted to raise as a Jew in Eretz Yisrael, but the father demanded his son back, the Israeli courts were contemplating extraditing her and had her in custody, as she was a flight risk. Reb Uri heard the story in the news, showed up at court and convinced the judge that she could stay in his home under house arrest — just so that a Jewish woman whom he’d never met wouldn’t have to sit in jail.

He once asked me to carry his siddur home from shul on Shabbos, and I snuck a peek inside. I found pages covered in cramped writing, and I asked him about it, but he brushed me off. Later, someone close to him told me he wrote specific kabbalistic kavanos that he would keep in mind while he was davening. He davened for so many people, and he would keep interest and ask for updates on the people he davened for.

Because of our proximity to the airport, oftentimes when he had a connecting flight, he would daven in the neighborhood and eat breakfast with us. His personality was a joy to be around, and yet despite his greatness, he was full of humility and so well grounded, and he retained his incredible sense of humor. He enjoyed a joke, but he especially loved a good vort, listening to divrei Torah, and telling one over himself.

Reb Uri once took a trip to America for Lev L’achim and his return flight got cancelled, stranding him here for Shabbos without proper clothing. Lev L’achim were of course, happy to do whatever was necessary, including outfit him for Shabbos, but as soon as he returned home, he paid back the value of the clothes in full, so as not to take a penny from tzedakah.

As Hashgachah has it, my family is preparing for our annual Lev L’achim breakfast this very Sunday — our first without Reb Uri in This World. But now he’s needed for something else: Reb Uri always spoke about Mashiach, and it was not just a far-off idea for him. He felt it, it was real. There would always be surprise in his voice that Mashiach had still not arrived, because to him, every day that Mashiach wasn’t here was a chiddush. Now he has another job to do.

Yehi zichro baruch.

Avi Lazar is CEO of Mishpacha’s North American operations.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 914)

Oops! We could not locate your form.