Colors in the Dark

Those paintings of the soul that the Soviets failed to find are now in Jerusalem, where the backstory can finally be told

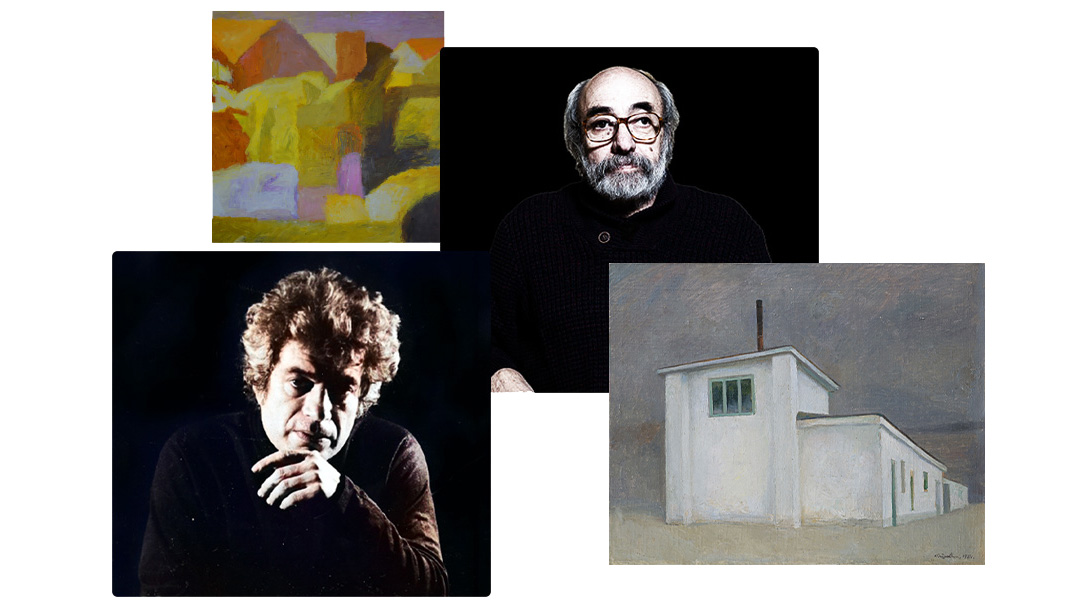

Photos: Elchanan Kotler

Behind the Iron Curtain, hidden away from the eyes of the KGB, two Jewish artists — each in a different city under different circumstances — sat and painted Jewish motifs with brushes, tears, and no little fear.

Years later, as their lives became joined through their children, those paintings of the soul that the Soviets failed to find are now in Jerusalem, where the backstory can finally be told.

Visitors walk through the exhibit, whispering to each other as they examine the paintings on the walls, studying the lines and colors as they try to decipher the hidden riddles the canvases hold.

But one person knows the secrets. “The fact that these paintings are being exhibited at all, and especially here in Jerusalem, is something that can’t be taken for granted, even nearly 30 years after my father’s death. My father nearly burned this entire collection. He was terrified of being discovered. And now, decades later, they’re finally seeing the light.”

His name is Rabbi Meir Ostrovsky, and he’s actually a big piece of the puzzle connecting this exhibit — now showing in Jerusalem’s Heichal Shlomo museum until the end of December — with the artists who created it. This is a joint exhibition of Rabbi Ostrovsky’s father, the late Yosef Ostrovsky, and his father-in-law, artist Michael Morgenstern. But the two mechutanim have more than a son and daughter in common — for they embody a modern history of Jewish art behind the Iron Curtain, where anyone creating Jewish themes or expressing a Jewish spirit could easily face Soviet imprisonment.

“People don’t realize what we went through in the Soviet Union. They don’t know that these paintings hanging here are literally a miracle,” says 67-year-old Michoel Morgenstern, sitting in a wheelchair (he suffers from a neurological condition) beside his son-in-law.

Because it’s a story that goes beyond art. It’s a testament to the possibility of returning to one’s heritage, of finding Hashem and connecting back to Yiddishkeit, and a revelation of the Hashgachah pratis that has accompanied them on their physical and spiritual journeys.

Oops! We could not locate your form.