Code Crackers

| June 12, 2019

M

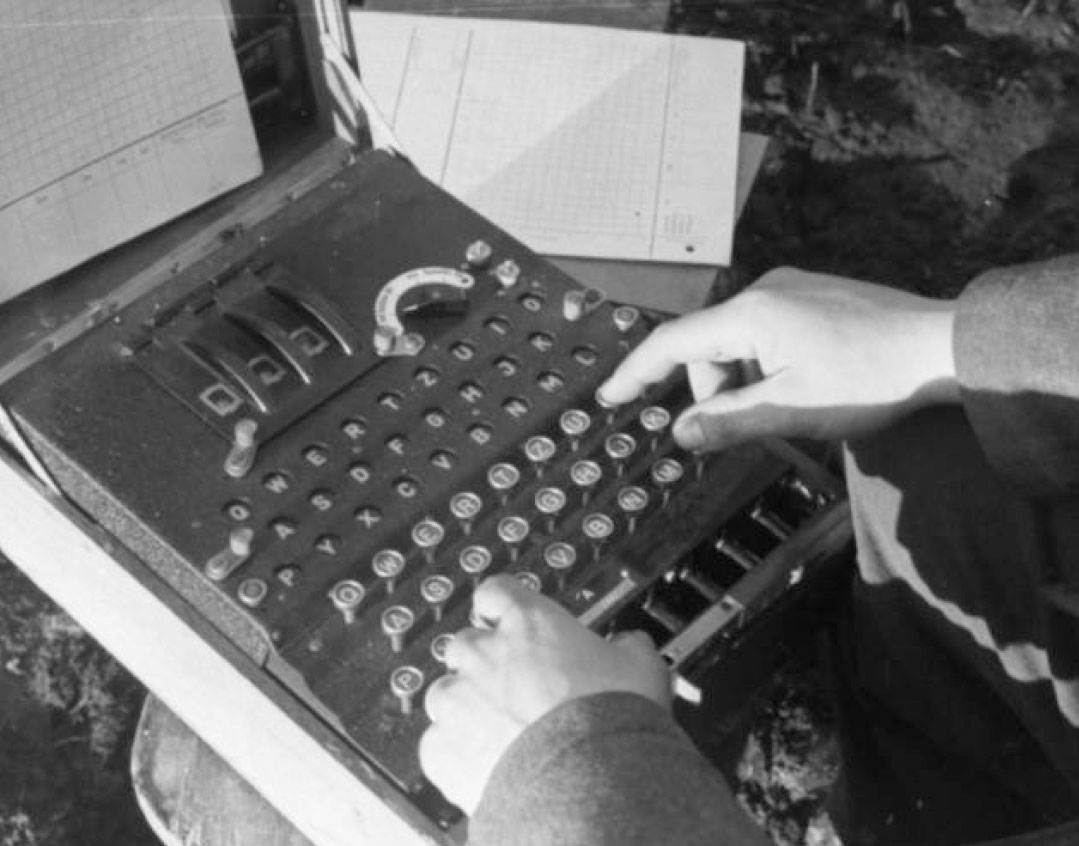

idnight, on a German command vehicle somewhere in occupied France. A Wehrmacht commander dictates a brief but vital message to his communications officer, who types the message into a device that resembles an ordinary typewriter. The encrypted message is then dictated to a Morse Code signaller, who radios the message to Berlin. In Berlin, the encrypted message is received and typed into an identical machine, known as the Enigma. What appeared as jumbled text moments ago now appears as coherent commands.

By way of the Enigma, the Germany army, navy, and air force sent orders to their troops and reports back home to Berlin. As the Germany army advanced in Europe and North Africa, Allied forces scrambled to decipher the code and access vital intelligence. The Germans believed their code was unbreakable.

At Bletchley Park, a country estate one hour outside of London, the brainiest men and women in Britain were quietly but determinedly proving the Nazis wrong. Though the Enigma machine could produce 159 sextillion settings — which the three branches of the military changed every day — British code-breakers knew that solving the Enigma could help them win the war. And so they went to work.

Historians surmise that the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, otherwise known as Station X, shortened World War II by at least two years by cracking the code. Among the greatest achievements of these British code-breakers was identifying German U-boat positions, which saved tens of thousands of lives on the Atlantic Ocean. The code-breakers also assisted the Allied advance into Africa and confirmed that Hitler fully believed the disinformation campaign that the Allies would land at Calais on D-Day, leading to a surprise attack at Normandy.

Mystery of the Enigma

A German firm invented the Enigma machine in 1918, and the German military adopted its use in the 1920s. The machine had a regular keyboard but was also built with three movable rotors that scrambled the letters in millions of different ways. The machine operator could strike the letter “H” and “I” would appear. The next time she struck the letter “H” a “T” would appear, depending on the rotor settings. A separate plugboard on the bottom of the machine offered another layer — up to ten alphabetical plugs could be switched to randomly exchange letters. Those settings were changed every night at midnight.

Polish mathematicians working at Poznan University gained access to the machine and broke its code by 1933. But as World War II approached, the German military made the Enigma even more complex, adding two additional rotors for a total of five, creating a total of 159 quintillion (that’s a billion trillion) possible settings. The Polish did not have the resources to build code-breaking machines of such complexity.

So one weekend, they invited French and British agents to Warsaw and handed over the Enigma machine. Even while British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was proudly waving a piece of paper that he said would bring peace to Europe, British intelligence knew that war was coming.

(Excerpted from Mishpacha, Issue 764)

Oops! We could not locate your form.