Client: Project Inspire

| August 6, 2024“The interviews should show how, in these trying times, we realize that our differences are not really important”

Client: Project Inspire

Objective: Full-length Feature

Film locations: Locations throughout Eretz Yisrael

Project Deadline: Tishah B’Av 5784

The Proposal

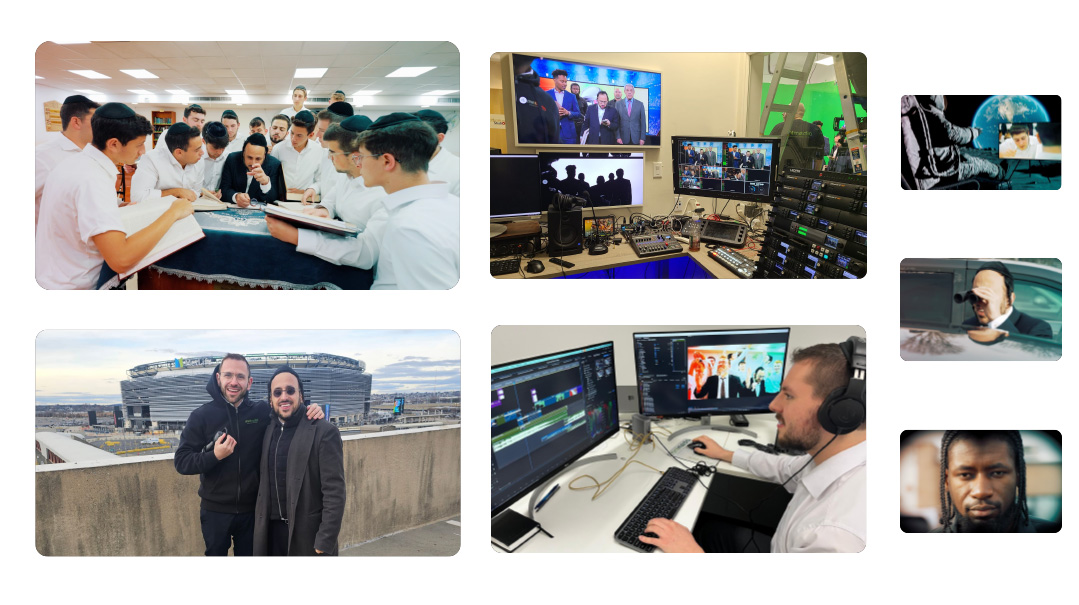

Rabbi Yossi Friedman, executive director at Project Inspire, reached out to us in May to discuss their annual Tishah B’Av video (this is our third time doing it for them).

“I think it has to be about the war in Eretz Yisrael,” he told us. “It’s all-consuming, it’s all anyone can think about, really — and there are a lot of powerful angles we can highlight for an inspirational video.”

A full-length feature can run close to an hour, or 15 times as long as the average four-minute video we produce. It’s a mammoth undertaking, and we spoke several times about our plan. Yossi wanted to feature three stories of people personally affected by the war: two families of hostages and one injured soldier.

“It can’t just be a tearjerker,” he warned. “Our goal with this video is always to inspire change and growth, so the interviews should show how, in these trying times, we realize that our differences are not really important.”

That became one of our main objectives while editing the video: to highlight Klal Yisrael’s achdus.

Location Logistics

On a logistical level, this year’s project presented some unique challenges. We work with some excellent crews around the world, but recording every single interview — hours and hours of footage — in Eretz Yisrael made everything a little more complex.

In addition to the long-distance arrangements, some of the people we wanted to speak to still had family members in captivity; their availability was iffy and they couldn’t commit too much in advance. Fortunately, Project Inspire’s program director Danielle Hass was on scene to arrange much of the scheduling, and her ability to make last-minute changes helped everything run smoothly.

Another challenge was the location of the shoots. To capture the emotion of one of the families, the crew went down to their neighborhood in Kibbutz Nir Oz. We were warned there would be strict security measures — they evacuated the kibbutz on October 7 and have not yet returned — but the family told us they would take care of the arrangements.

“Just give your names to the guard at the booth,” they said.

When the crew got there, it felt more like they were entering an upscale resort than a war-ravaged area, with the soldier at the checkpoint consulting her pad: “Are you here with such-and-such organization? No? Are you ‘one of Dan’s friends from work who is coming over after 5?’” (Apparently someone had actually given that name-description for the clearance list.) She eventually found the right names, and they were allowed in.

We also conducted several hours of filming on the roof of Aish HaTorah, with its iconic view overlooking the Kosel Plaza. It is a gorgeous location, but it is completely exposed, which means it is both very bright and sunny, and very hot. We plotted the sun’s path on a diagram to figure out the best timing and angle for our video shoot, because while it’s a nice place to visit, holding a long interview there is quite a challenge.

Danielle Hass actually held up an umbrella over the interview subject, both to control the lighting and to prevent him from getting heatstroke. Our cinematographer, Yirmi Vann, didn’t have the luxury of shade though, and he did end up getting sick by the end of the day’s shoot.

It’s All about the Angles

Although much of our video content comes from sit-down interviews, our interviewer doesn’t usually make an appearance in the actual shot — he’s just there to help prompt the interviewee. With this project though, Rabbi Friedman felt it was important to have the interviewer be part of the scene as well. He suggested renowned journalist Sivan Rahav-Meir, as her experience gives her the sensitivity to ask the difficult questions, and she is comfortable on camera.

From a content perspective, this was a powerful move. We always coach our interviewees to give full answers in complete sentences; for example, the response to, “Where were you born?” should be, “I was born in Brooklyn, New York” as opposed to “Brooklyn.” But we know there will invariably be content that isn’t understandable without including the question (and therefore the interviewer).

This is even more relevant when it comes to very emotional pieces, where the most powerful sound bite might be silence, or just a word or two. Using Sivan as part of the content gave us the opportunity to be more flexible in such cases, because her questions are part of the story itself and her reactions to a subject’s answer let the emotion breathe as well. There was a section of interview where the mother explained how she was able to see her son’s phone tracker (and her son with it) actually crossing over the border to Gaza. It was a very intense moment, and being able to show a reaction from Sivan — just reflective listening, nodding along, and sharing the pain — gives viewers a chance to absorb the impact.

However, this setup does bring its own challenges; with Sivan facing the interviewee, we had to adjust the cameras and lighting in a way that we could have a clear view of both of their faces but not the equipment behind them.

Language of the Heart

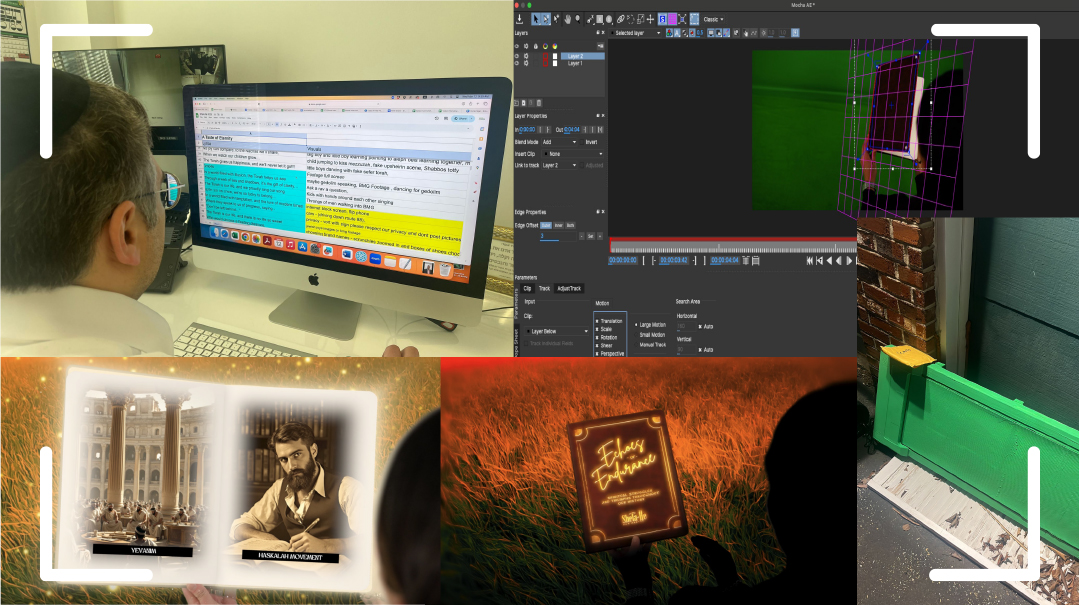

Once we had all of the interviews on our servers, our next hurdle was that all of the content was in Hebrew. Though our senior editor Mrs. Rivky Liebenstein has a basic understanding of the language, the ability to carry a conversation in Hebrew is different than the nitty gritty editing of a fast-paced interview with all of its back-and-forth.

At first, we thought about having a translator transcribe the footage, but with the sheer volume of the content — over ten hours of interview footage — it made more sense to use a software that automatically adds English subtitles. It was far from perfect, though, because it took things very literally. For example, one of our main stories was about a family named Shem-Tov, but the program didn’t recognize it as a surname and kept writing “good-name.”

Figures of speech and idioms didn’t always translate well, either; when a mother refers to her son as a “yeled shemesh,” she’s calling him a ray of sunshine, but the software’s literal translation of “sun-boy” doesn’t quite give over her intent. It was a good enough start, though, so we planned to start with the software’s subtitles and then correct all issues in later editing stages.

There were times that working off the subtitles was too stiff, though. Much of the content is highly emotional, raw, and vulnerable, and the editing in those sections is less about polished syntax than about capturing those feelings. Mrs. Liebenstein actually turned off the subtitles, relying on her basic knowledge of the language, to allow for more of an intuitive editing process. Working off of subtitles can feel almost like editing a document, but in video-editing the emotion and passion is as important as the words themselves.

Editing is always an intense process, and doing it in a foreign language can take a lot of energy. It was a Tuesday morning toward the end of the project when Mrs. Leibenstein found that the editing was suddenly moving much faster than usual. It took her a moment to realize that she had finally gotten to the one English interview!

Digging Deep

We always ask the client to share their print graphics with us — logos, slogans, general branding — because video gives us the flexibility to bring these images to life. If the client’s graphics depict broken glass over their text, we can build an animation to show the whole process, not just one moment that the picture would allow. In such a case we might start with a whole piece of glass and then show the glass shattering to reveal the text underneath. When graphics show a medallion on an angle, we can make it spin in a 360-degree circle.

When VFX associate Mrs. Shayna Koppenheim (formerly Goldman — we wrote about her shidduch here a few months ago) saw Project Inspire’s graphics with a Hamas tunnel, though, she wanted to do something special.

“You see how it’s an image of a tunnel?” — she pointed at her screen — “I could animate it, or I could build an actual 3D tunnel of our own.”

She ended up spending close to a week designing an entire space, adding graffiti on the walls, piping, and even a missile on the floor. This “real” tunnel with depth meant we could have text appear in the tunnel as we’re pulling the viewer deeper and deeper into the space. Project Inspire’s graphics were powerful, but this brought them to a whole new level.

Callback

Aside from the physical strain of the sun and heat filming on the Aish HaTorah roof, the intense nature of the interviews was emotionally taxing. Everyone was taking a much-needed break when a shy couple walked onto the roof — the young man was clearly about to propose!

Our cinematographer Yirmi Vann had actually started his career as a wedding photographer, and he took several pictures for the new couple. This was just what our crew needed. There they were, several draining hours into discussing the plight of the hostages. It was sad, emotional, and almost hopeless — but the innocent joy of a new couple injected a little bit of cheer into the gloomy atmosphere. We could see the light at the end of the tunnel.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1023)

Oops! We could not locate your form.