Clean Break

| November 28, 2023Anything would be worth it if it would help us have a baby

As told to Shterna Lazaroff

February 2018

I looked in the mirror and grumbled. More acne? No, please no.

I was 29 already — and hadn’t even dealt with breakouts during my teenage years. Why now?

My mother popped her head in to check on me. “Ready for your date, Sari?” she asked.

Almost. First, I needed more coverup.

The next morning, I slept in late. The date had been a dud — again. And I was tired. I texted my personal trainer to cancel. It wasn’t the first time I’d done that, either. Lately, I was in a constant state of no energy.

“I’m fine,” I told my parents when they pointed out my recent exhaustion. I was still in the middle of recovering from a bad breakup. The bad skin, thinning hair, and complete lack of energy made sense to me. I’m a psychologist, after all. I know what the physical stress symptoms are.

But at a just-in-case appointment with my dermatologist, she disagreed. “I want to do bloodwork,” she told me. Yes, emotions can release themselves physically, but she argued that sometimes we gave our emotions too much credit. “I wouldn’t want to say ‘stress’ and then later find out there was something medical going on.”

Turns out, my dermatologist was right. When the lab called, they said my thyroid numbers were completely off. Apparently, I had Hashimoto’s, an autoimmune disorder in which your body attacks your thyroid. My thyroid wasn’t producing hormones correctly, but baruch Hashem it could be treated with medication.

I went on medications and within six weeks, my skin was clear. I could start working out again. My hair grew back.

Everything was back to normal.

September 2019

You don’t become an older single overnight. First, you’re 19 and going on your first date. Then you date a few more people, have a few more disappointing endings, people start suggesting that you consider fertility preservation treatments, and you realize that you’re 30.

I was thinking about making an appointment with a fertility specialist, but then another shidduch was suggested.

Great, I thought. Now I can push it off a bit. Let’s see how this goes first.

I figured I’d call the doctor after this dating saga ended, as I was pretty sure it would. I hadn’t given up on marriage, but I’d become okay with life as it was. I had a wonderful family, amazing friends, meaningful work. If I could find someone to share that with, great. But I wasn’t going to live life waiting for it to get better.

Either way, at least the date would give me an excuse to push off the appointment.

February 2020

Turns out, that “just one date” had been very promising. Now I was back in front of the mirror, preparing for another date. And the acne was back. I needed to schedule an appointment with my endocrinologist, but I’d been busy. In the months since December, things had gotten serious.

It looked like I might even be getting engaged.

If so, I shouldn’t ignore my thyroid anymore.

I should readjust my medications so my skin is back to normal before the wedding, I thought, and finally scheduled to meet my doctor.

“How are you doing, Sari?” the doctor asked as I relaxed into the chair. Honestly, I was excited about the opportunity to be still for a few minutes. Between dating and work, I’d barely had a moment to breathe all week. The doctor and I chatted about the rumors of that virus from China as he poked around my neck with the machine. And poked. And poked.

It was taking longer than my usual routine sonograms to check my thyroid.

“Is everything all right?”

“I’m worried about this.” He turned the screen to show me a nodule on my thyroid. “It’s darker than it should be, so I want to run a biopsy and check it out.”

March 18, 2020

I was in the Pesach kitchen making chocolate pudding to stock the freezer. “Things changed so suddenly,” I told my mother. In a matter of days, schools had closed, stores shut, and the world went into lockdown.

And seconds later, my world changed, too.

The doctor called with my biopsy results. He said something about “bad genes” and “risk of cancer” and stats like “50 percent.” He was curt and unclear.

I leaned against the counter, took a deep breath, tried to steady my tone, and asked, “Are you saying I have a 50 percent chance of developing thyroid cancer?”

The doctor didn’t pause before responding. He didn’t ease me into it. Within moments of answering the phone, he told me that phrase no one ever wants to hear. “No, there’s a 100 percent chance — you have cancer. The 50 percent is about treatment protocols.”

I stared at the phone, my mind blank, my heart numb. Around me, the remnants of Pesach prep seemed to fade away. I had no idea what to make of it — this news I wasn’t ever expecting.

What had happened? What on earth was going on?

I was supposed to be getting engaged — how did I end up with cancer?

Later that night, I lay awake and stared at the ceiling. Of course, this was happening to me.

When I’m finally, finally about to get engaged at 29, I get diagnosed with cancer.

I knew Tzali was planning to propose. But instead of saying yes, I’d have to explain: I have cancer now.

How on earth would I tell him?

“What’s going on?” Tzali asked.

I’d been unfocused ever since we arrived at the park. And I’d barely said a word the whole car ride over.

How exactly was I supposed to communicate this?

I know you want to get married, but I can’t.

I like you, too, but I have cancer.

I’d love to marry you, but—

“Just tell me,” Tzali said.

Deep breath, another. You got this.

“If I tell you, you might change your mind about marrying me.”

He tried to lighten the mood with a laugh. “What could be that bad?”

“Cancer.”

And then I told him everything — the biopsy, the results, and the treatments I would need. I looked at him and waited for him to stand up, say goodbye, and leave me behind.

“I don’t care. We’ll deal with it,” he said.

Later that month, we got engaged.

AS I made the first dinner for Tzali in our new apartment, I thought about my wedding — and a huge part of me was sad. In many ways, I’d been robbed of my engagement. My mother and I would go look at flowers, and I’d have to leave the meeting to take a call from the hospital. People would wish me a future full of happiness, and I wondered what exactly that future would contain.

I waited more than a decade to be engaged. What I’d dreamed of was happening, but I couldn’t fully enjoy it.

My surgery was scheduled for a few days after sheva brachos. We just needed to get through that — and then we’d finally be able to be the happy-go-lucky newlyweds again. No more cancer. No more surgeries looming ahead.

The doctor promised my case was pretty simple. I had clean margins, no spread. They’d be able to get everything out at once, with a single surgery, and then I’d be fine.

Oh, and they had to warn me that there was a tiny, tiny chance I would need radiation. But don’t worry — that wouldn’t happen.

“It’s as unlikely as getting struck by lightning twice,” the doctor reassured us. We didn’t yet know — I’m pretty great at defying the odds.

After I recovered from surgery, I felt like shanah rishonah could finally begin. I’d finally found my person; I’d be cured from cancer. Now we could enjoy the life Hashem had given us.

It was all worth it, I kept thinking. A long, winding journey, but it had all led here, and here is a good place to be.

May 2021

I was right. After the surgery, Tzali and I finally got to be that newlywed couple. We ditched the doctors and traveled the world instead. We finished surgeries and started on our new life together. All that remained of my cancer was the routine appointments I needed every year or so, just in case.

“I’m here for my scans,” I told the secretary on that spring morning. She checked me in and let me know that it would only be a few minutes. The doctor was finishing up with another patient and then it would be my turn to check on my thyroid.

“How are you?” the doctor asked.

“Never better,” I said as he spread the cold gel over my throat. We chatted as he pressed the ultrasound probe into my neck and examined the images on the machine.

After a few seconds, though, his talk slowed, then stopped. He peered more intently at the monitor. Finally, he swung the machine around to show me. “Sari, we need to talk.”

I knew that tone. I knew that look. And after enough scans, I even knew what that was on the screen.

“Cancer?” I asked.

“Yep.”

This time, it was a malignant lymph node at the base of my neck. My oncologist recommended we treat it with radioactive iodine, which was basically radiation, but in pill form.

The doctor explained that I would go on an iodine-free diet for a few weeks. The thyroid would be starved of iodine, so as soon as I took the iodine-radiation pill, my desperately deprived thyroid would pull the iodine — and radiation — straight there.

“How do you know the radiation won’t affect any other parts of my body?” I asked him. Conventional radiation treatments are very precisely targeted, beaming the energy at the exact spot of the body where the cancer is found. Here, I’d be swallowing a pill.

“Complications are very rare,” the physician told me.

As a newlywed looking forward to building a family, I had one thing on my mind. “Is there any chance this could affect my fertility? Could it end up in my ovaries?”

“It’s rare,” he repeated.

At that point, I’d beat the odds too many times. If something was unlikely, I took that to understand it would probably happen to me.

The OB/GYN handed me a tissue. I’d just finished sharing my whole story — the cancer, the recurrence, the suggested treatment, and my fears. My cheeks were wet.

“What if I can’t have kids after the radiation?” I asked.

My doctor had a glimmer — were those tears? — in his eyes. He waited for me to wipe my eyes before sharing his thoughts.

“Professionally, I’d remind you that you only have a one percent chance of that happening. But if you were my daughter, I would suggest that you undergo treatment to preserve your fertility beforehand.” That way, if radiation went wrong, I’d have a backup plan.

It was ironic. I thought that by finally marrying, I’d be able to sidestep that part of being an “older single.” But here I was about to start the process anyway.

I put down the stack of magazines — I was too restless to read any of them — and observed the crowd in the waiting room instead. It was funny, actually. Couples, couples, couples. Then me and my mom. “People are probably so confused,” I whispered. “Who comes to a fertility clinic with their mother instead of their husband?”

But everything had spiraled so fast — the news we’d received, the advice from ATIME, the psak we got from our rav — that Tzali couldn’t even get home from his business trip in time for the appointment ATIME arranged for me.

Within minutes of meeting Dr. Rybak, I knew we were in good hands. He took the time to answer my questions, calm me down, and reassure me that Hashem was on our side. “You’re only 31 — young and healthy. Preventive measures like these are usually very straightforward in your circumstances.”

His sonographer came in to take some images of my ovaries. I knew the drill by now — the cold cream, the poking. And soon, I recognized the next part of the drill as well: that all-too-familiar look of concern on his face.

Dr. Rybak took a peek and sighed. “You have fewer follicles than we’d expect for someone of your age.”

“What does that even mean?” I was confused. What happens now?

“We try anyway and daven for the best.”

The cars in front of me weren’t moving at all. I sent a quick message to my office. Standstill traffic, coming probably an hour late.

My office would be okay with it — but the hormones wouldn’t forgive me for being in traffic. As part of my treatment, I needed to inject myself twice a day, exactly 12 hours apart. If I was even a little bit late, it would throw everything off. But I was stuck in traffic.

And that’s how I ended up injecting myself as I drove down the BQE. I used one hand to hold the wheel and another to stab the needle.

I hope I don’t get a ticket. It would have been a hard scene to explain away.

But I couldn’t afford to forfeit this cycle. We’d already done three — unsuccessfully. And time was running out.

My oncologist was only letting me postpone radiation for a little while. If I didn’t find out that I was expecting soon, he would push me to do the treatment, even if I hadn’t yet preserved my fertility.

On our first round, the doctors initially thought they had good news — until they began examining the genetic material they’d retrieved, and it literally disintegrated.

I wasn’t in the lab with them, but I later heard that my operating doctor had cried. She knew I had cancer. She knew how important that treatment was. And she broke down too when she saw everything fall apart before her.

“I’m so sorry,” Dr. Rybak said when he gave me the recap. “We have nothing.” And then he warned me, “These treatments might not actually work.” But he also promised me with one of the kindest tones I’ve ever heard, “We won’t stop trying.”

After that first cycle, when we left that appointment, I cried for the future we were losing. Everything had disappeared so fast. One day I was hoping to get married. The next, I had cancer, more cancer, and — boom — basically no chance of having a child.

“We’re haven’t even been married a year yet!” I sobbed to my husband. We didn’t even get to enjoy our shanah rishonah; we’d been interrupted by crisis after crisis.

I felt bad that Tzali had even married me — he didn’t need to settle for a sick, damaged girl. He could have easily had healthy children. Instead, he was trailing after me from doctor to doctor, trying to cure my cancer and hoping that maybe, just maybe, we’d be lucky enough to have a child.

“I’m not going to the doctor,” I told Tzali. There was no doubt what the oncologist would say.

He’d already let me push off treatment. He’d given us the chance to attempt fertility-preserving treatments, but we failed. We’d reached the end of the rope — we’d ignored reality for as long as possible.

Tzali insisted I go to the oncologist, accompanying me to the doctor. My husband made me go, but as soon as we got to the office, I told the doctor exactly how I felt. “I don’t want treatment until I know I’ll be able to have a family.”

He sighed. I’d already had this fight with him before.

“You know what? Let’s take some new scans and decide from there.” The scan had good news and bad news. The bad: I still had cancer. The good: It hadn’t grown at all since my last appointment.

The doctor clicked his pen and thought a moment before he spoke. “Here’s what I’m going to suggest. If nothing’s changed, it means this is a very slow-growing, non-aggressive cancer. A lot of people think ‘cancer’ always means ‘fight right now.’ But in some cases, it’s just as responsible to watch and wait — if you monitor the situation very carefully and regularly. I feel comfortable telling you that we could put cancer treatment on pause while you focus on preserving your fertility.”

My shoulders fell in relief. “You mean I can continue IVF?”

“Yes,” he said. “But we’re going to keep monitoring your cancer. As long as nothing changes, you can keep going.” As my husband and I walked out of the office, he called after us.

“Go on — I want to hear good news from you!”

I cracked the spine of the book and got reading. Someone in the fertility clinic waiting room had recommended It Starts with the Egg as a primer. It was written by Rebecca Fett after going through several rounds of IVF — and barely any luck with healthy retrievals.

Rebecca wasn’t ready to give up. As a biochemist, Rebecca knew how to research, so she dug deep into whatever she could find. Was there any way to improve the quality of her eggs — and therefore improve the chance of successful retrievals, lower the chance of miscarriage, and improve her chance of becoming a mother?

In the book, she breaks down her findings. At this point, we live in a world where we just accept certain things as standard — we don’t question that there are chemicals in our food, in packaging, or floating in the air around us.

But the chemicals from processed items are a recent phenomenon — and they filter down to a woman’s oocytes. When they are exposed to things like phthalates, PBA, or other inflammatory items, the quality of the genetic material will diminish. The studies weren’t new, just vastly ignored or unknown.

And for most people, not knowing is fine. They’re healthy enough that even if the quality is affected, they’ll still be fertile, but when someone is struggling to get successful retrievals, these chemical exposures can make all the difference.

So Rebecca decided to cut all these out — no more sugar, no more plastic, no more unhealthy foods. She made a three-month commitment to herself (since oocytes start maturing 90 days before ovulation), and her next IVF cycle was incredibly successful.

I was intrigued. What Rebecca was suggesting was crazy, but I wanted a baby badly enough to give it a shot.

The wise people recommend taking it easy and starting by only eliminating the worst offenders, but I felt like if this was my one chance, I wanted to go all the way. My lifestyle shift was extreme. Everyone thought I was crazy — but they already thought that when I paused cancer treatment to try and have a baby, so I didn’t care.

I looked through my cosmetic shelf. If any moisturizer, shampoo, or cream had a scent — I threw it out. And even if it didn’t smell like much, I still checked to make sure there were no neutral fragrances in the ingredients. Artificial smells usually include phthalates, a chemical that’s known to reduce estrogen levels. I stopped walking into any of the local stores that had diffusers on. Those things were pumping the air with phthalates, and for every moment that I shopped, I was absorbing the chemicals — which, just like the scent, would stick to me in the weeks to come.

I also stopped wearing nail polish and pared down my makeup collection. Our skin is our biggest organ and I wanted to make sure that if anything sat on it, it was something I would be comfortable absorbing. As a general rule, I focused on things that took up more real estate. Mascara was less of a concern because eyelashes are basically dead cells, but anything on my skin — like concealer or foundation — couldn’t contain BPA or phthalates. Forget about lipstick. We basically eat that, so I refused to put on any unless it was chemical-free.

I’d always been pretty healthy, so I thought the kitchen changes wouldn’t be so extreme — but they were, because it wasn’t only the food items that needed to go. Studies show that the chemicals in our utensils or packaging (like BPAs) leak into the food. It’s even worse when the utensils or packages are heated — the heat basically cooks the chemicals right into whatever we’re about to ingest. I wasn’t going to let that happen.

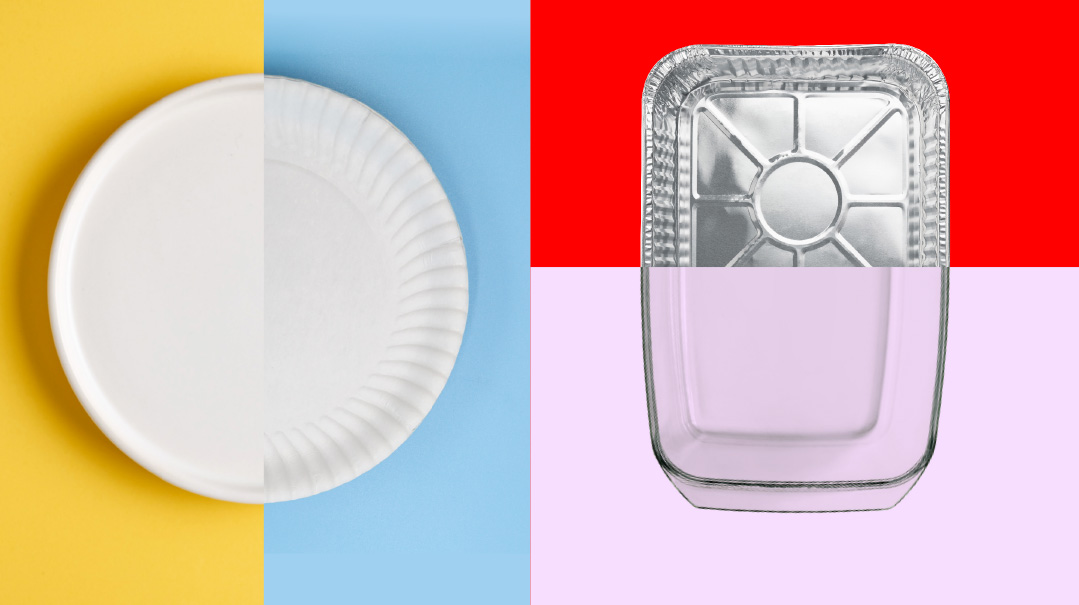

I unplugged our microwave so it wouldn’t emit any of the dangerous waves (and so I wouldn’t be tempted to heat up my food in plastic), and I rummaged through my pantry to throw out any plastic containers and single-use items. I replaced everything with glass, stopped buying aluminum foil, and threw out all my nonstick pans. Yes, so much of it was officially “BPA-free,” but they were laden with BPA alternatives like BPS and BPF.

Even plastic one-use water bottles didn’t come into the house anymore. Yes, they might be cool right now sitting in my pantry, but what about in the warehouse? How do I know it didn’t get hot enough for the chemicals from the bottle to seep into the water?

I started cringing when I saw people put hot food in to-go containers or heating up a baby bottle in the microwave. I couldn’t watch them cook the chemicals into their food.

I overhauled our menu to get rid of sugar and anything processed — all of which are said to affect your hormone balance. Instead, I only bought organic. On a typical day, I’d start with juice on an empty stomach, then either overnight oats, a smoothie bowl, or cut-up fruit. Lunch was the most challenging for me because I had to prep in advance with limited options, so most days, I had the same thing — a salad with heavy proteins added in.

One of the hardest changes was eliminating animal protein, which my nutritionist recommended.

Dinner always started with tears — I felt like I had nothing to make — but eventually it became a fun and creative challenge. I would make my husband his regular animal proteins with chicken or meat and then make myself a separate meal. I had a lot of meat imitations like burgers or “meatballs” made from beans and went through basically all the gluten alternatives — brown rice pasta, cauliflower pizza (without cheese, of course). I used a lot of recipes from my nutritionist and followed others from the Beat Cancer Kitchen.

The most animal protein I had was fish once a week — and on top of that, I cut out inflammatory foods like gluten, soy, corn, dairy, and processed sugar. The holistic coach I worked with suggested this based on my specific areas of concern: infertility and cancer.

It was hard because I’ve always had a massive sweet tooth, and always needed something sweet after dinner. But after a while the thought of sugar stopped exciting me. I went from craving gushers after dinner every day to not even noticing when someone near me opened a pack.

I checked with the nurse at my fertility clinic beforehand, but every morning, together with my juice, I took as many as 30 different supplements I knew were good for diminished ovarian reserve. I was going to take whatever I knew might make even a small difference.

That’s what made me try acupuncture, too — an alternative healing method where a practitioner pricks you with tiny needles throughout the body. Of all the things I tried, I think this was one of the most helpful. When I started, my acupuncturist told me my nervous system was in major fight-or-flight mode, which makes sense because infertility is stressful — and I’ve always been a more anxious person. Acupuncture taught me how to slow down, relax, and reach more of a balance. I felt the difference daily.

Throughout all this — all these major, major changes — I tried to remind myself: There’s everything you’re able to do, and then there’s what Hashem wants to happen. I didn’t want to lose sight of the One directing it all. I made a point to prioritize davening Shacharis every day, saying Nishmas every night, and joined a group for Tefillas Chanah. I’d been part of Bonei Olam’s Ohel Sarala when I was single, so now I switched sides and davened for someone to get married while they davened for me to have kids.

And then I continued to hope and wish and wait.

February 2022

“Are you sure?”

“I’m positive.”

I couldn’t believe what the doctor was saying. After four fruitless cycles, we had finally proceeded to the next stage of treatment.

At that point, I was taking more than 30 vitamins a day, eating a basically vegetarian diet, and avoiding chemicals like the plague. But to be honest, I’d never thought it would actually work. All the extremism was just a way of reassuring myself. I needed to know that at the end of the day — whether we had a baby or not — I had exhausted every option.

I had tried everything in my power.

And apparently, it worked. Hashem had sent the miracle.

Because that cycle had been successful in retrieving high-quality genetic material, the doctor recommended we try one more in case we needed to rely on it in the future. We did another round, and baruch Hashem the retrieval succeeded beyond my earliest dreams.

The first few cycles, our prognosis had looked bleak. Now, we could finally dream of the family that — b’ezras Hashem — would one day be ours.

November

I hung up the phone, still in shock. It was one of the first times I’d gotten off the phone from a doctor’s office with good news. I put a hand on my stomach as though I would already be able to feel it.

“Tzali? You have a minute?” I never called him at work; I could hear the alarm in his voice when he answered. I had to work to keep my own voice even.

“The nurse called — we’re expecting.”

OFcourse, I still had cancer.

The only change was that I was, on doctor’s orders, completely ignoring it. We could have monitored it to check for growth, but I wasn’t going to do radiation during pregnancy anyway, so why bother?

“Have your baby and then we’ll assess,” the oncologist advised. I’m lucky I have a slow-growing cancer that gave me this leeway. It allowed me to spend nine months nurturing our baby and ensuring a healthy start at this wonderful life.

Cancer during pregnancy can go one of two ways. Pregnancy is designed to make things grow — the baby, our nails, our hair, and sometimes cancer. It’s also a transformative, healing time for mothers. I’ve heard enough stories to have hope; maybe my cancer won’t grow at all. Maybe it will disappear. It won’t be the first story of its kind. But for those months, I didn’t let myself think about it. My focus was on helping that little baby inside me grow.

Why did the treatments suddenly start working?

I wish I knew. I think the lifestyle changes played a huge part, but it wasn’t the only shift. My mindset went through a rehaul as well. At first, I panicked during every appointment.

Was it working? What did the ultrasound show? When would we know?

After a few failed rounds, I realized fear wasn’t helping me. Only Hashem was. Instead of letting anxiety build when I sat in the waiting room, I’d turn to Hashem and say, “I’m not in control of my fertility. I’m not in control, I’m not in control.” And I’d remind myself that He was — and He’d take care of me.

The only thing I could control was my behavior and my approach. I could choose to do anything I knew about within the realm of reality, such as adjusting my approach to health, and I could choose to loosen up, let go, and let Hashem care for me.

When I came to that realization, I felt calm. I was able to fully, fully accept that I was doing everything in my power to make this work. Therefore, I was at peace with whatever the outcome would be because I knew I would have no regrets. If I tried everything and still didn’t go home with a baby, clearly that’s what Hashem wanted — and I could live with that.

And for us, that utter commitment and sheer determination to change everything about my life led to a successful treatment — and eventually, our little baby.

When the doctors handed her to me in the delivery room, her little fingers immediately wrapped around mine. “People thought your mama was crazy,” I whispered as I nuzzled her sweet little cheeks. Near my bed, Tzali looked down at us with the kind of smile I’d never seen before — the glow of a parent. The pride of a father.

We’d both done so much to get here. I’d changed my entire lifestyle. Tzali had gone along with everything. I hugged my daughter closer and then passed her off so Tzali could have a turn.

I watched him hold our daughter for the first time and had no doubt at all.

Every moment was worth it.

“Sari,” the narrator of the story, can be contacted through Family First.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 870)

Oops! We could not locate your form.