Celebrating Freedom

Much of the Western world has ceased to appreciate the gift of liberty or to be willing to fight to protect it

T

he exodus of a group of slaves from Egypt, from servitude under the ancient world’s most powerful nation to freedom, has long served as the universal symbol of liberation. Not by accident did the spirituals sung by black slaves in the antebellum South rely on imagery straight out of the Hebrew Bible — of Moshe confronting Pharaoh to tell him, “Let my people go”; of the Jewish People crossing the “chilly and deep” waters of the Jordan to enter the Promised Land.

For thousands of years, Jews have been gathering on Leil Haseder to relate the story of how Hashem took them out of Egypt, from slavery to freedom, from servitude to redemption. They did so at a point in history when the very concept of freedom as a defining element of human life — certainly for every man, woman, and child of a particular society — did not even exist.

And we have continued to tell that story even in circumstances that looked every bit hopeless as that of the Hebrew slaves in Egypt — e.g., during the Spanish Inquisition, in Auschwitz. One of my sons commented at the Shabbos meal this week how he had just heard Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich describe the months of preparation that went into his preparation for a Seder in the Soviet Gulag. Some might have questioned what there was to celebrate under those conditions. But he did not. For he knew that even in prison, he was a free man.

The Soviets might kill him, but they could not break him. They could not take from him the knowledge that Hashem had taken the Jewish People to Him — lakachti — and lifted Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich to a realm above the Soviet prison, in which only his body was held prisoner.

And we continue to celebrate the wonder of the Divine gift of our ability to define ourselves as autonomous beings today, even as much of the Western world has ceased to appreciate the gift of liberty or to be willing to fight to protect it.

I can remember watching Ayaan Ali Hirsi being badgered by a Canadian TV host, who demanded to know how she could say that the Muslim society in which she was forced into child marriage to an elderly relative and subjected to bodily mutilation was a greater evil than “imperialist” America, exporting its culture around the world.

“Perhaps the difference is,” Ali Hirsi replied calmly, but with icy contempt, “is that I have lived in an unfree society. You have not.”

Those Yale Law students, and the majority of the law school who signed a letter condemning the Yale campus police for clearing them from a room in which they were loudly disrupting a panel discussion, would do well to contemplate life in totalitarian societies, in which ideas cannot be debated, and for which they are laying the groundwork.

For their reading list, I would start with the account of a young Iraqi Shiite in the first heady days after the US victory in the first Gulf War — and before America had betrayed them by leaving Saddam Hussein in power — that appeared many years ago in the New Republic. She described the excitement of being able to openly share her feelings with another human being, without worrying that the other person was a government informer, for the first time in her life.

No doubt a high percentage of those Yale Law students, protesting the appearance on their turf of an attorney who had successfully represented religious clients in the Supreme Court against the maximalist demands of the LGBTQ community, were Jewish. But I doubt any of them had ever attended a Seder where the Maharal’s definition of lechem oni — the bread of poverty — was discussed as a symbol of human freedom to define oneself.

The poor man, writes the Maharal, stands between the slave, on the one hand, and the rich man, on the other. The former cannot exercise his free will and define himself, because he is subject to the will of his master. But the rich man’s free will is also impaired. For he is often possessed by his possessions to the point that he cannot define any purpose to his life beyond the attainment of more things.

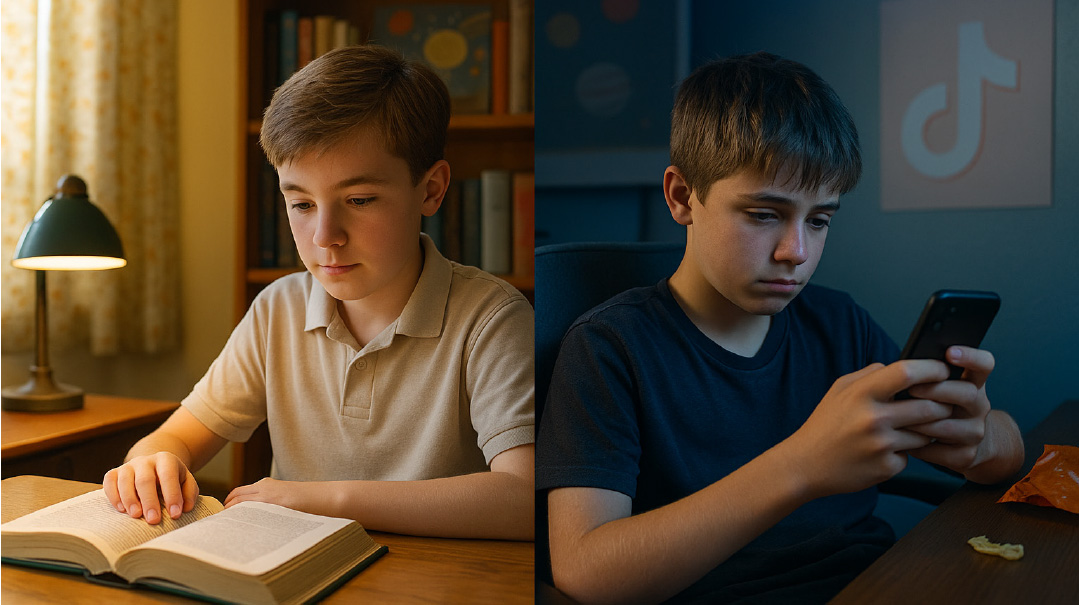

CHAZAL TELL US, “There is no genuinely free man other than one who is deeply involved in Torah study.” For without the self-mastery and perfection of middos that comes from involvement in Torah, one cannot focus on where he wants his life to go or find the discipline to get there without being distracted at every turn.

My rav, Rabbi Shlomo Klagsbald, a Bnei Brak native, recently shared with me the following story about Rav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l. When the time came to marry off the Kanievskys’ youngest child, someone offered to take care of all the arrangements — wedding hall, food, etc. — for $10,000. Rav Chaim happily agreed to have the burden removed, and told the man to meet him in front of Kollel Chazon Ish the following Sunday morning at five minutes to nine.

At the appointed time, Rav Chaim reached into his inside coat pocket and discovered that the money had disappeared, apparently through a hole in the inside pocket. He begged the forgiveness of the person who had offered to help, and asked him to meet him the next day.

Word soon spread in Bnei Brak of Rav Chaim’s loss. Meanwhile, in one of the local chadarim, a young talmid was happily passing out $100 bills to his classmates. He had walked to cheder on the same path Rav Chaim had taken to kollel, and found the path littered with bills.

The cheder rebbi put two and two together, and realized that the bills in question were undoubtedly from the ones lost by Rav Chaim. He gathered the bills from the talmidim, and told the original finder that they would return them to Rav Chaim after the Minchah minyan at which he always davened.

But when they approached Rav Chaim, he first asked the boy what time he had left his home for cheder. Upon hearing 9 a.m., Rav Chaim said that he had already despaired of the money by then, so no matter what kind of siman there might have been (let us leave that halachic issue aside), he could not claim the money as a found object.

Upon his rebbi’s urging, the boy offered the money to Rav Chaim as a present, but Rav Chaim told him that the money belonged to his father and not to him. He added, “Sonei matanos yichiyeh — One who hates presents will live.”

That evening, the boy’s father came to Rav Chaim and proffered the recovered money. Rav Chaim accepted the money, and immediately took from the sum returned to him ten percent as maaser, which he promptly gave to the father of the boy who had found it, a kollel avreich. (The story of Rav Chaim’s loss had already reached his father-in-law, Rav Elyashiv, and the latter had contacted Rav Chaim to assure him that if the father returned the money, sonei matanos did not apply to this circumstance.)

That is how Rabbi Klagsbald told me the story. But when he was done, he confessed that he had left out the real point he wanted me to grasp. What had Rav Chaim done upon discovering the loss of an amount that represented a fortune for him? Absolutely nothing. At 9 a.m., he sat down at his shtender and began learning, as he did every morning.

He did not retrace his steps. He did not bid some fellow kollel members to join him in a search. It was as if nothing had happened.

Could there have been a freer person in the world than Rav Chaim? So great was his control over his emotions that nothing could distract or disturb him — certainly not the loss of mere money, no matter how large the sum. That freedom too is a measure of what we aspire to on Pesach.

Chag kasher v’sameiach.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 907. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.