Castles in the Air

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman still wants peace even after October 7

Photos: AP Images

An enlightened despot who is determined to propel his country into a modern future, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman still wants peace even after October 7. But as his Pharaonic building projects are scaled back, will a breakthrough with Israel likewise vanish like a desert mirage?

ON Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coast, a massive construction project is underway. Satellite images show hundreds of excavators literally moving mountains to carve a massive furrow into the landscape. The manmade canyon is some 70 to 150 meters wide, extending dozens of miles to the east into Saudi Arabia’s interior.

Information on the megaproject is patchy; analysts have noticed unusual gaps in the images taken by commercial satellite firms, suggesting that a deep-pocketed customer has been buying them up to keep details of construction progress secret.

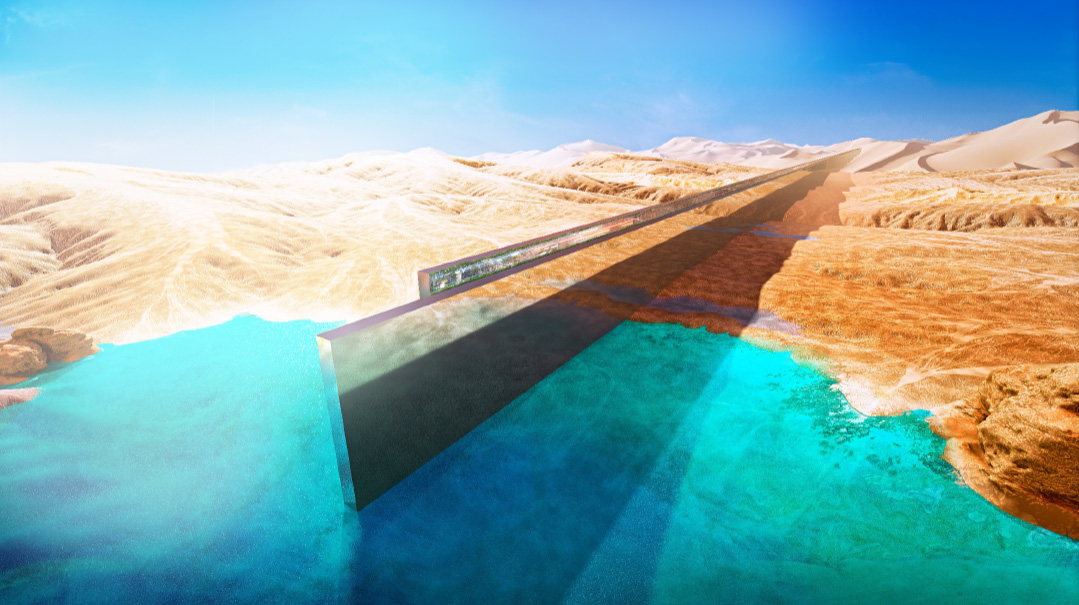

All this attention is focused on “The Line,” a stupendous moonshot of a civil engineering project in the form of a blade-like, glass-walled city meant to stretch for 105 miles across the Saudi desert. (That distance would span the width of the state of Connecticut, from Stamford through New Haven and Norwich, all the way to the border with Rhode Island.) The Line is only the most eye-catching district of a new city, called NEOM, Saudi Arabia’s answer to the Gulf states glitz and Chinese megaprojects.

For sheer Pharaonic megalomania, it’s hard to beat, and it’s all the brainchild of one man: Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, the de facto ruler of the desert kingdom.

All of this should matter to Israel, its neighbor along the Red Sea. Because The Line is one giant metaphor slashed through the desert sands for the leadership of its chief visionary.

Known as MBS, Bin Salman is the Arabian version of an enlightened despot — determined to thrust his people forward to a better future, and willing to trample anyone in his way. He has introduced elements of westernization in the face of the kingdom’s Wahhabi clerics, but at the same time has ordered the dismemberment of a pesky journalist in the country’s embassy in Turkey.

The friends that MBS keeps are even more telling. In the halcyon days of the Trump administration, he hobnobbed with Jared Kushner and his Jewish team, with a side helping of Mossad chief Yossi Cohen. Clearly, MBS feels little obligation to anti-Israel history, but is he the man to complete the breakthrough with the Arab world?

The answer to that question partly depends on the enigma of who exactly the imposing MBS actually is. When the crown prince greenlighted the Abraham Accords in 2020, it was a clear signal of approval for the historic realignment in Israel’s favor from the man set to rule the Arabian peninsula’s anchor state for decades to come. Despite the shockwaves of Hamas’s attack on Israel, the messages coming out of Riyadh are that MBS hasn’t changed his mind, and he still views an opening to Israel as the way forward for his country.

So the metaphor of The Line becomes relevant. Rumors of a drastic scaling-back of plans signal that notwithstanding the lavish PR around the project, it has run into trouble. Despite the diggers in the desert, the gouges in the Saudi wasteland may be all that remains of the audacious plans.

The same questions hover over peace with the Saudis. Even if Israel isn’t required to make an Oslo-style sacrifice of its security for a piece of paper, can the crown prince deliver? Could MBS take his fundamentalist country with him, or is the Israeli-Saudi breakthrough destined to remain a mirage in the Arabian sands?

The Saudi Crown Prince meets Jared Kushnerin the halcyon days of the Abraham Accords

Brave New World

The sense that Israel was nearing an agreement with the most important Arab state, the cradle of Islam, was palpable late last year. In a conversation with Fox News last September, Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman sent waves of excitement through diplomatic circles. “Every day we get closer” to normalization with Israel, he said.

In a sign that the issues — at least from Israel’s side — had left the realm of geopolitics, Pirchei Yerushalayim, the famous Jerusalem boys’ choir, had even come out with a new song: “Shalom Lach, Saudia,” which it performed during an appearance at the Jerusalem municipality’s succah. The Jewish New Year began with a presentiment of peace, and many thought that Prime Minister Netanyahu was about to pull off the greatest diplomatic coup of his career.

The crown prince of six years had shown signs of affinity for Israel even before he became the kingdom’s de facto ruler. In 2016, he met with a delegation of influential Americans from various fields. MBS was then minister of defense and deputy crown prince, and was already a rising force in the kingdom. In a long and wide-ranging discussion, MBS surprised his guests when he mentioned Israel.

“Israel is not our enemy,” he reportedly said, according to New York Times journalist Ben Hubbard in his book MBS. “Israelis don’t kill Saudis.”

Two years later, in the spring of 2018, by then the crown prince, MBS received a royal welcome from the Trump administration during his visit to the United States. MBS sat down for an interview with the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg. When Goldberg asked about Israel, the crown prince replied that Saudis have no problem with the Jews.

While declaring that both Israelis and Palestinians “deserve to have their own state,” he expressed sympathy for the Jewish state: “Israel is a big economy compared to their size, and it’s a growing economy, and of course there are a lot of interests we share with Israel.”

MBS described Iran, on the other hand, in terms that even Binyamin Netanyahu wouldn’t use. “I believe that the Iranian supreme leader makes Hitler look good,” MBS told Goldberg. While Hitler only sought to conquer Europe, the crown prince explained, the Iranian supreme leader was looking to conquer the entire world. “They’re both evil people, and he’s the Hitler of the Middle East.”

MBS made the basis of his suspicions of Iran clear: He believes that Iran has set its eyes on Mecca, the Muslim world’s holiest city, of which Saudi Arabia is the custodian. MBS had no intention of waiting for Iran to strike and was seeking to forge regional alliances. Israel, as far as he is concerned, is a natural ally.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have close ties, and generally, the UAE doesn’t pursue significant diplomatic initiatives without prior coordination with Riyadh. Saudi Arabia supported the UAE’s decision to sign a peace treaty with Israel, and gave Bahrain a green light to join the Abraham Accords — even helping to facilitate the agreements by allowing flights through its airspace between Israel and those Gulf countries.

The Biden administration interrupted the Abraham Accords ushered in by Trump, but it also sees an opportunity in Saudi Arabia’s ambitions. Saudi Arabia, for its part, is not motivated by philo-Semitism or even shared interests; it’s also seeking to procure advanced weapons systems from the US, as well as approval for a nuclear program.

And so, despite reports last summer that Saudi peace was drifting away, MBS made very clear on September 20, 2023, a few days after Rosh Hashanah, that his eyes were still fixed on the goal and peace was imminent.

Then came the horrific Simchas Torah massacre. Israel launched a counteroffensive, and Saudi Arabia suspended the talks. Since then, there have been conflicting reports. MBS convened an emergency pan-Arab conference calling for international intervention in Gaza. Saudi Arabia has also stated several times that normalization would be conditioned on the establishment of a Palestinian state. Over the past month, however, there have been signs that preliminary agreements have been reached, and that peace could once again be on the horizon.

For all his public statements, MBS sees the Palestinians as an irritant — a problem that needs to be solved, but hardly a cause that speaks to his soul. This hasn’t always been the case. There was a time when Saudi Arabia posed a real threat to the world at large, and to Israel in particular.

MBS’s big-thinking is revealed in his brainchild, an immense blade-like city called The Line, a computer-generated version of which is shown here

Path to Power

Mohammed bin Salman, 39 this August, was a cipher for the first half of his life. When he first came to international attention, even his exact birthdate wasn’t known.

Mohammed is the eldest son of his mother, third wife of King Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud. His father, Salman, the 25th son of the founder of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Ibn Saud, served as governor of Riyadh for 53 years before becoming king.

Mohammed’s half-brothers were educated at prestigious universities abroad. Sultan, his father’s second son, flew aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery, becoming the first Muslim astronaut. Fahd, the eldest, was involved in horse racing in Britain. Ahmed, the third, who served in the Saudi Air Force, owned a racehorse that won the Kentucky Derby. Their mother came from a wealthy and well-established urban family. Mohammed’s mother came from a tribal family, and his older brothers taunted him as “the Bedouin.” He remained in Riyadh for his higher education, studying at King Saud University.

But his older brothers’ absence abroad only served to draw Mohammed closer to his father, which would prove fateful. So would the deaths of two older brothers, Fahd and Ahmed, apparently of heart disease, in their forties. Their father, Salman, took their deaths very hard, and the young Mohammed tried to take their place.

Salman, today elderly and incapacitated, had an iron work ethic as governor of Riyadh Province. He’d show up to work every day at 8 a.m., even into his seventies. Mohammed was at his father’s side from the age of 16, learning how to manage the tribal balance of power in the large province.

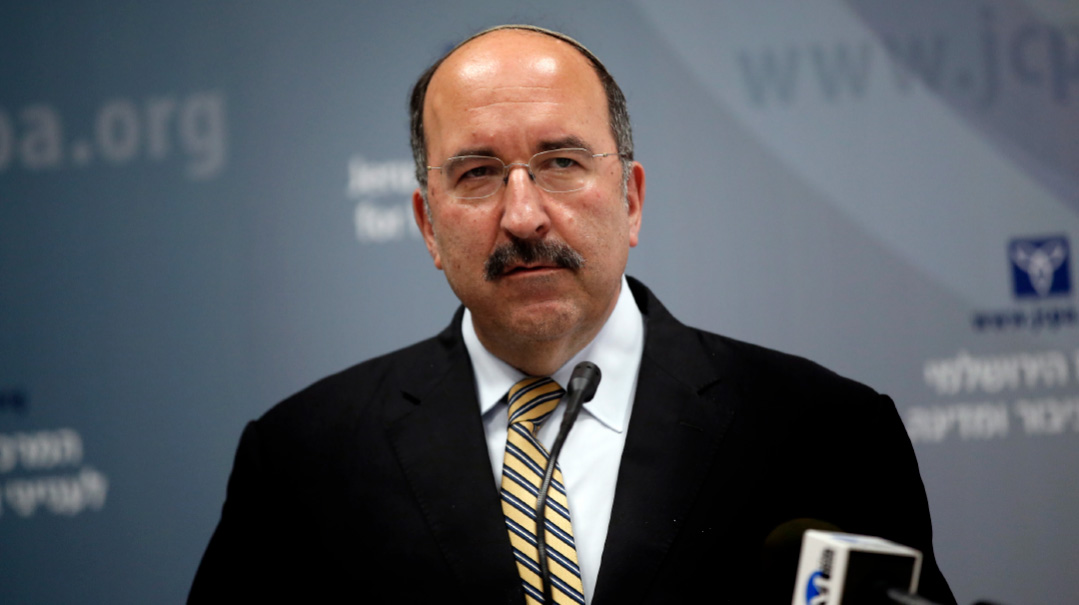

It was around this time that America was attacked on 9/11. The attack was masterminded by Saudi militant Osama bin Laden. All eyes turned to Saudi Arabia, and for good reason. In his 2003 book Hatred’s Kingdom: How Saudi Arabia Supports the New Global Terrorism, Dore Gold, Israel’s former UN ambassador, Binyamin Netanyahu’s political advisor, and longtime president of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, pointed to Saudi Arabia as the fount of global terrorism. Gold carefully documented how Saudi Arabia had disseminated the radical Wahhabi ideology, seeking to impose radical Islam on the world. The kingdom bankrolled terrorist groups and openly supported Hamas.

“Back in the 1990s, Saudi Arabia was one of Hamas’s main sources of funding,” Gold tells Mishpacha. “And in my book, there are pictures of Hamas leaders sitting in conferences in Saudi Arabia. At the time, I estimated between 50 and 70 percent of the Hamas budget came from the Saudis.”

Saudi Arabia, Gold wrote in his book, continued to support Hamas even while giving lip service to the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Gold raised the question: What about al-Qaeda? If Saudi Arabia was supporting Hamas, and a host of other terrorist organizations in the Middle East and beyond, why wouldn’t it support al-Qaeda? The Saudis had enabled 9/11 and didn’t seem to see the need to change.

It was in this milieu that young Mohammed Bin Salman came of age. His father noted that his son absorbed the spirit of his country well, even though he had grown up playing video games and would later turn out to prefer more modern ways. Saudi Arabia’s religious police, the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, goes so far as to beat men who publicly wear shorts; that wasn’t exactly MBS’s thing.

“Saudi Arabia has taken a revolutionary new direction.” Israel’s former UN ambassador Dore Gold contends that Israel should give MBS a chance

Money Man

As a prince in the House of Saud, Mohammed could hardly be said to have grown up in poverty. But he grew up envious of other princes in wealthier households. Mohammed didn’t sail on superyachts, and he likely didn’t get to attend the same parties as some of his cousins.

Not much is known about the prince’s financial affairs in his early twenties. Unlike his older brothers, he didn’t manage huge investments or head large companies. But he did trade stocks. Riyadh money managers suspected him of engaging in “pump and dump,” — a practice common at the time — making a massive purchase of shares of a worthless stock, talking it up, and selling it for a huge profit when the price surges.

Mohammed also dabbled in real estate, which earned him a nickname that haunts him to this day: “Abu Rasasa” — the father of the bullet. Legend has it that when a judge ruled against him in a property dispute, an enraged Mohammed sent him a bullet (some say two) in the mail. Although the crown prince reportedly hates the nickname, it has nevertheless stuck. The royal family claims the anecdote was fabricated to slander him.

Above all, MBS aspired to power. One of his childhood heroes was Alexander the Great. Another was the UK’s Iron Lady, Margaret Thatcher. Acquaintances said he loved talking about how she jumpstarted Britain’s economy — something he clearly hoped to do to his own country.

Outsider Inside

The greatness he aspired to must have seemed distant indeed when Mohammed was young. His grandfather Abdulaziz al-Saud established a system of succession for his 45 sons, of whom Salman, Mohammed’s father, was the 25th. After Abdulaziz’s death in 1932, the crown passed down through the chain of sons. More and more of them died, but there were still two sons left between Salman and his brother, the reigning King Abdullah. Bin Salman could aspire to high office, but he wasn’t in the line of succession.

That all changed when the two brothers between Salman and the throne suddenly died, in October 2011 and June 2012, respectively. At the age of 77, Salman found himself anointed crown prince. Despite Mohammed’s lack of experience and relatively poor English, Salman chose him as chief of the Crown Prince Court over his brothers due to his knowledge of the country and culture. Mohammed came to the attention of the international press, and some began asking who this mysterious new character was.

Then, three years later, came the moment MBS had dreamed of. In January 2015, King Abdullah died, and Salman, Mohammed’s father and crown prince, became king of Saudi Arabia at 79. Salman immediately appointed Mohammed as defense minister. But he also appointed Mohammed Bin Nayef (MBN) as crown prince, while MBS became deputy crown prince. MBN, who served as interior minister, was the cabinet member most respected by the West. His agenda included an uncompromising war against global terrorism. He was Saudi Arabia’s liaison with British and American intelligence, developing deep ties with the CIA.

One of MBS’s first steps was to launch a war against Yemen, which had been taken over by the Iranian-sponsored Houthis in 2014, and had descended into chaos. MBS decided that it was necessary to eradicate that threat, believing the war would be over in a matter of weeks. He only notified the US at the last moment. The Houthis continued to receive weapons and support from Tehran, and the war continues to this day.

Saudi Pharaoh

MBS’s mega-ambitions for his country emerged early on. In 2016, a few months after his appointment as deputy crown prince, Saudi Arabia announced the Vision 2030 plan, MBS’s pet project. The plan sought to free Saudi Arabia from its dependence on oil, a goal the kingdom has sought unsuccessfully since the 1970s. The program was to be implemented over three five-year phases. It called for changes in government investment policy but also for easing the kingdom’s strict religious policies. A country where musical performances were once prohibited now has public concerts and sporting events.

Saudi Arabia sought to attract foreign investment, and began hosting delegations of American businesspeople and policy makers. That’s when MBS began to make noises about peace with Israel. The move made sense from multiple perspectives. First of all, Israel was emerging as an ally against Iran.

Former Israeli ambassador to Washington and current minister for strategic affairs Ron Dermer spoke about this impetus in a 2020 interview in these pages. “If you think about it from the Arab states’ point of view,” he said, “what you see is an Iranian tiger, and you have an 800-pound American gorilla that is leaving the building, and they look around and see a 250-pound gorilla with a kippah on, and they say, well, you know, we’d like to have a strong partnership with you.”

Added to that, said Dermer, was the economic impetus. “Israel always had a miraculous story to tell, but we were not a factor in the calculation of countries when it came to their economies. Yet in this age of innovation, Israel is a global technological power.”

In the legitimacy stakes, too, a Saudi Arabia bent on burnishing its image to Western investors — as it has been with the massive acquisition of Western sports teams — found a close relationship with Israel useful.

Starting in 2019, the kingdom began to revise its school textbooks, which until then had spread Wahhabi hatred not only for Israel, but also for Christians and all non-Muslims. These books didn’t only influence children in Saudi Arabia; they’re used in schools all over the Arab world and have been a persistent source of anti-Semitism. The State of Israel, for example, wasn’t shown on maps of the region.

The IMPACT-se research institute, which tracks the content of these textbooks, just published its 2024 report, highlighting changes made in the past year. The most important ones: The name “Palestine” was removed from maps, Jews are no longer depicted as apes and pigs, references to “infidels” have been removed, and other violent content has been toned down.

Sea Change

At their heart, MBS’s reforms reflected a generational shift. For his book MBS, New York Times writer Ben Hubbard interviewed Rob Malley, a notoriously anti-Israel official in the Obama administration who also headed up negotiations with Iran for a new nuclear deal under Biden. (Malley was suspended from his job under suspicion of passing classified material to Tehran.) Malley had met with MBS and gave Hubbard his thoughts.

“MBS comes from a generation of Saudi leaders that doesn’t have a visceral, emotional attachment to the Palestinian cause,” Malley said. MBS considered the Israel-Palestinian conflict “an annoying irritant — a problem to be overcome rather than a conflict to be fairly resolved.”

MBS found other things to admire in Israel: its economy, its military, and its intelligence services. Looking to the future, given the proximity of NEOM to Israel and its dynamic technology sector, MBS likely considered an eventual role for the Jewish state in his planned city’s future.

Also pushing MBS toward Israel was his interest in pleasing not only Trump, but Kushner, who was working on a plan to break the Israeli-Palestinian impasse and was counting on Saudi help to do so.

While in New York, MBS had an off-the-record meeting with pro-Israel American Jewish leaders. The Americans were sworn to silence over the discussion, but some leaks suggested that MBS surprised them by bashing the Palestinian leadership. One credible report said he criticized them for rejecting previous peace offers, and they should “agree to come to the table or shut up and stop complaining.”

Later that year, he welcomed to his Riyadh palace a delegation of American evangelicals led by Joel C. Rosenberg, a Jewish author with Israeli citizenship whose sons served in the IDF. One of them, in fact, was the delegation’s note taker. Such a meeting would have been unthinkable for previous Saudi leaders. The only portion of their two-hour talk that MBS asked his guests to keep private was about Israel and the peace process.

“He was quite candid, quite surprising in some of the things he said,” Rosenberg told Mishpacha. “But he asked that that not be for public consumption.”

In public, MBS was more guarded, and his father, King Salman, reiterated the kingdom’s traditional support for the Palestinians. MBS has said that any future moves with Israel depend on a Palestinian peace agreement, and he called the Trump administration’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital “painful.” But the fact that the likely next ruler of Saudi Arabia sees Israel not as a foe but as a legitimate neighbor with shared political and economic interests could lead to a lasting realignment of the Middle East.

Under MBS, contacts between Israel and the Saudis went from being back-channel via Jewish interlocutors to discreetly face-to-face. According to foreign reports, Netanyahu and Bin Salman have met on several occasions, at least one of them on Saudi soil. In November 2020, the two leaders met in the Saudi city of NEOM on the Red Sea coast, together with then-US secretary of state Mike Pompeo and then-Mossad chief Yossi Cohen. The small Israeli delegation spent nearly four hours in Saudi Arabia and returned directly to Israel following the meeting.

Right Direction

While normalization waits in the wings, MBS’s vision, first expressed in 2016, is already a fact on the ground. “There’s no question that Saudi Arabia has taken a revolutionary new direction,” says Dore Gold. “That wasn’t evident when I wrote my book about the Saudis back in the days after September 11. At the time, I was convinced that Saudi Arabia was one of the sources of radical Islamic hatred of the West.”

Gold uses the example of Saudi support for Hamas to emphasize his point. “Do you know how much money Hamas gets today from Saudi Arabia? Zero. That is a tangible change that should not be ignored by anyone.”

The question is what led to this sea-change, and what that could mean going forward. Gold believes the Saudis are also reassessing their domestic policies. “My theory is after 9/11, the Saudis did a reappraisal and decided that they no longer wanted to be associated with funding terrorism,” he says. “I think it would be irresponsible for anyone to ignore the revolutionary changes that were going on in Saudi Arabia. Take, for example, the special police that are there to monitor the religious adherence. They took it apart. He dismantled it by his own orders.

“I wrote the book before this happened. But as someone who’s monitored Saudi Arabia carefully, I think it’s not the same Saudi Arabia anymore. What I’m saying has a certain credibility that many other Middle East analysts don’t have.”

Gold is hesitant, however, to forecast any time frames for when peace will come. “I don’t look into crystal balls. I look at trends, and the trend I’m seeing is that Saudi Arabia is moving in the direction of stability and progress.

“Saudi Arabia comes out of the Wahhabi Islamic tradition, which Western academics said was always very conservative. They are moving away from that, and one has to understand where they’re coming from. When I wrote my book, Saudi Arabia was exporting these Wahhabi traditions all over the Islamic world. It wasn’t just in Saudi Arabia — it was in the former Soviet Union, it was in Indonesia, it was in Africa. But then they put the brakes on this major religious tradition that was coming out of their own country. And I think it came out of a sincere redefinition of what an Islamic state should be doing.

“I’ll give you a story that will exemplify this. In the past, there was an international Islamic organization called the World Muslim League, based in Mecca, and it was the vehicle for exporting Wahhabi ideology around the world. Now, the World Muslim League has changed. For example, in 2020 the head of the World Muslim League, Sheikh Mohammed Al–Issa, decided to visit Auschwitz. That’s a big change in terms of what they think they should be doing, and it indicates a readiness to embrace a more ecumenical world viewpoint.”

Outraged by the dismemberment of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi embassy in Ankara, Biden vowed to make MBS a “pariah.” The inevitable climbdown led to the infamous, and embarrassing fist bump in place of a handshake

Internal Battles

Before he could advance his agenda of peace with Israel, MBS had a significant hurdle to overcome in the form of his cousin Mohammed bin Nayef (MBN), still next in line to succeed the aging king. While it’s unclear exactly what happened, the Economist’s Nicolas Pelham claims that MBN was summoned to a meeting with King Salman in Mecca, only to be detained and pressured into declaring loyalty to MBS and abdicating as crown prince. King Salman signed off on this palace coup, and MBS reached the second highest position in the kingdom.

Now he could turn to his most grandiose plan yet, which ties into his desire for normalization with Israel. In the summer of 2017, MBS presented NEOM, the biggest development megaproject ever. Media outlets and influencers from all over the world were invited to the launch at Riyadh’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel.

Part of the kingdom’s plan to diversify its economy from oil production, a new urban area will be developed in Tabuk Province, bordering Jordan along the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba. The area will be entirely reliant on green energy and desalinated water; even the extracted salt will be used for industry. The name given to the new area, NEOM, is a portmanteau of the Greek word neo, for “new,” and the first letter of mustaqbal, Arabic for “future.”

The highlight of this bombastic project is The Line, a linear city 200 meters wide, enclosed by a mirrored 500-meter-high wall on each side, stretching over 170 kilometers. The city was originally planned to house 9 million people by 2030, with all needs and services accessible within walking distance. It will be a zero-emission city —no cars, and transit infrastructure enabling rapid end-to-end travel.

At the Red Sea end of the project will be the Oxagon, an industrial city located right along the route of 13 percent of the world’s maritime trade, on the way to the Suez Canal. Trojena, a mountain ski area intended to host the 2029 Asian Winter Games, will be built nearby, as will Sindhala, a resort island.

NEOM’s original price tag: $500 billion. Many international companies and entities have come aboard and invested in the project. MBS is looking to turn the region into a hub of innovation in every field, and this is where Israel fits in. With NEOM’s borders only about 20 kilometers by land from Eilat, integrating Israel into this plan seems natural.

As ever, MBS was playing a double game: modernizing his country, and at the same time, exerting an ever-greater grip on domestic power. He took advantage of the conference at which the project was presented to lure many Saudi princes abroad back to Saudi Arabia. No one anticipated what happened next; immediately after the conference, these princes discovered that the luxurious hotels in which they were staying were a gilded prison. They were pressured into admitting to financial crimes and forced to part with a considerable portion of their fortunes. The result: $100 billion for NEOM’s investment fund.

Power Games

A Saudi citizen we were interviewing for an article in February of 2017 bristled when we mentioned the regime’s heavy-handed treatment.

“It’s not the regime,” he insisted. “It’s the people, they’re too conservative.”

We’re paraphrasing; the actual term he used was far more insulting. When we took him to task for speaking that way about his countrymen, he replied, “Wait and see. The regime is pushing the people forward, it just needs to move slowly.”

Seven months later, MBS proved him right. Saudi Arabia announced in September 2017 that women would soon be able to obtain driver’s licenses, for the first time in the kingdom’s history. The world applauded MBS for this progress.

But the honeymoon didn’t last long. Westerners could look the other way when it came to the rough treatment of MBN and the crackdown on Saudi princes, but not when it came to the grisly killing of a regime critic. This was journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who entered the Saudi embassy in Istanbul to settle his divorce papers. He didn’t leave alive, and it later emerged that he’d been murdered and dismembered inside the embassy.

The backlash was immediate. Saudi Arabia tried several culprits and sentenced them to death, claiming they’d acted on their own initiative, but the world didn’t buy it. A 2021 US intelligence report found that MBS gave the order for the execution. Many companies withdrew their money and involvement, from Saudi Arabia in general and NEOM in particular. MBS learned the hard way what the West’s red lines are.

Despite this, MBS was able to keep some lines of communication open. The Trump administration was very sympathetic to MBS, who had forged personal ties with Jared Kushner. Kushner was partly responsible for MBS’s interest in normalization with Israel, as the crown prince knew that this would please the president’s son-in-law, an architect of the Abraham Accords. The two maintained an unofficial back channel, and after the Jamal Khashoggi assassination, Kushner kept texting with MBS about the issue, despite the protocols. After Kushner left the White House, Saudi Arabia’s wealth fund invested $2 billion in his investment firm.

MBS has steered his country’s investments in new directions, including sports. In 2021 Saudi investors acquired Newcastle United Football Club in England’s Premier League. The Reuben brothers, a Jewish family of Iraqi origin that ranks third in wealth in the UK, are also partners in that acquisition. MBS also invested in LIV, a new golf competition that has become one of the largest in the world; cricket, horse racing, wrestling, Formula One motor racing, and tennis.

Dore Gold believes that MBS’s investments in sports are a legitimate attempt to diversify Saudi Arabia’s portfolio, not just “sportswashing,” as the attempt to launder the country’s image by investing in iconic sports teams is called. If we’re looking for problems, he points out, we should look further east, to Qatar.

“I think in the case of Qatar, you have something far more sinister and far more problematic. But that’s not Saudi Arabia. That’s an example of a country that’s buying football teams. If you’re looking for who’s buying influence, look at who’s buying whole departments of universities. That’s Qatar.”

With pro-Palestinian campus demonstrations ongoing, his words are a potent reminder that someone’s pulling the strings behind the scenes — and it’s not Saudi Arabia.

Educated at home instead of in the West like his more worldly siblings, MBS (pictured here with his father King Salman) rose to power because of his local knowledge

Facts on the Ground

While some countries resumed investing openly in Saudi Arabia in 2021, MBS’s flagship project, NEOM, has run into difficulties. The Line was scheduled to start being populated next year, but its estimated costs have reportedly tripled to $1.5 trillion, and rumors of major hitches began circulating last April. Despite the rumors, Saudi Arabia has announced more planned features of the NEOM area, such as cultural, musical, recreational, high tech, and scientific centers. The most recent of these was announced a month ago.

Saudi Arabia denied a late April Bloomberg report that it had made significant cuts to the program, claiming “the project continues as planned.” But the report was revealed to be true. The first major element to be cut: the $1.5 billion water desalination program. In addition, it turns out that by 2030, The Line will span only 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) with a planned population of 300,000 people, far fewer than the original 9 million. It will still be a groundbreaking structure, but with dwindling funds and huge costs, the project is not progressing as planned.

Saudi Arabia, for its part, continues to advertise that 140,000 people from over 100 nationalities are working on the project on the ground, and the first power turbines have already arrived.

As reality bites, the crown prince is learning that fantastic petro-dollar wealth doesn’t equal limitless power. Will the scaling back of this fantasy parallel the quiet demise of a breakthrough with Israel? As the Biden administration seeks a giant foreign policy win in the form of a grand Middle Eastern bargain, there are major questions for Israel. With 64 percent of Israelis saying that peace with Saudi Arabia isn’t worth the price of a Palestinian state, is a “warm peace” with the Wahhabi kingdom such a prize anyway?

Gold believes that peace with Israel is part of this process, though there’s a qualifier: “Again, the pace of diplomacy can sometimes be very slow. I think they need time to incorporate changes, but I have confidence that MBS and the people around him want to move in a good direction, and we have to have patience, and we have to speak quietly with them and not be in the newspaper every day.

Dore Gold recalls the Vietnam-War-era slogan: “Give peace a chance,” concluding, “I think you’ve got to give Saudi Arabia a chance.”

With reporting by Gedalia Guttentag

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1015)

Oops! We could not locate your form.