Cast Your Bread

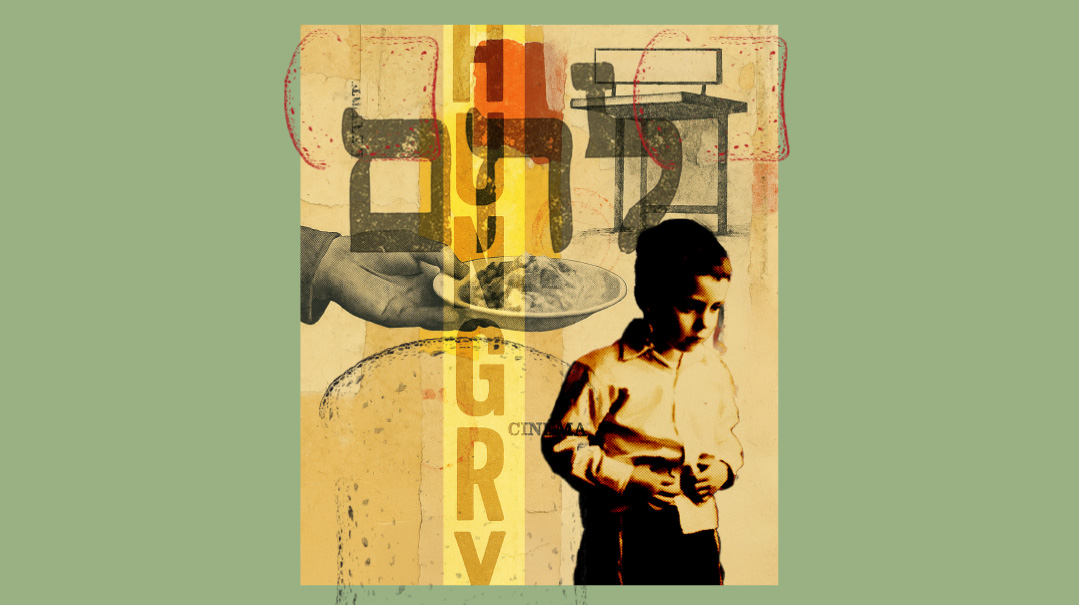

| September 30, 2025You’ve heard the expression “Going to bed hungry”? I doubt you really know what it means

What’s a little kid to do when his stomach is growling all day, when he knows he’ll be going to bed hungry until that one chocolate spread sandwich the next day? That little kid was me — until Hashem sent my salvation through an astute custodian with a huge heart.

N

ight was always the hardest part.

You’ve heard the expression “Going to bed hungry”? I doubt you really know what it means. And even if you do, probably not like this. My small stomach growled constantly. Hunger made me dizzy. Lying on the old bed, I thought about one thing only: food. I’d flip through those little Machanayim booklets, stare at the drawings of Hechtkopf, the illustrator whose characters all us kids knew, and fix my eyes on the steaming dishes in the pictures of the kretchmes of Eastern Europe.

The whole day had passed with almost nothing to eat, but there was no one to complain to — everyone at home was in the same boat. Poverty was our reality, our decree of fate, and in our house, there were no exceptions.

The house itself showed it. Paint peeled from the walls, the ceiling beams poking through the crumbling plaster. After hunger, the cold hit hardest. Jerusalem’s biting frost. We had no heating, as there was no money for gas. At any moment the electric company could cut us off, and the phone line had already been disconnected for half a year, but what mattered most to me wasn’t gas, electricity, or phones. It was the empty refrigerator. Because that was about survival.

This wasn’t some third world country in the early 1900s. This was, believe it or not, Jerusalem in the 1990s — and yes, despite the tzedakah and chesed committees, there were still pockets of real, hunger-pang poverty. I was the oldest of what would be ten children, growing up in Ramot Polin, the “honeycomb” buildings of Ramot that fulfilled some architect’s dream. My father learned Torah day and night, and my mother devoted herself to raising her brood, all close in age. There was plenty of Torah and yiras Shamayim in our home, but no material comfort. Just grinding poverty.

Ramot Polin then was a closed, conservative neighborhood with almost no dropouts. The families were primarily avreichim — men in kollel who had managed to get into Kollel Polin or received government-subsidized apartments through Amidar, the state-owned housing company. For almost everyone, life was simple, modest. Cars were rare — usually just one or two in the entire parking lot. Most families relied on buses or walked.

But for some reason, our financial situation was the worst of all. While our neighbors managed, in our house even the bare minimum was missing. Every evening after kollel, my father would run from gemach to gemach, borrowing here, paying there, juggling endless debts. Just trying to keep his head above water.

And I was just a little kid who wanted food.

All week long I waited for Shabbos, when the refrigerator would be a little fuller, when I could actually taste a piece of chicken or fish. On Thursdays, when fruits and vegetables were bought for Shabbos, the sight of them drove us wild. By Friday they were already gone — devoured. If you wanted to see what longing looked like, you could come into our house on Thursday and watch us line up to stare at the bag of nectarines fresh from the shuk.

The test was unbearable.

Thursday night, when the house was asleep, we would creep to the half-empty fridge, terrified at every crinkle of the fruit bag (it made a racket in the silence), and steal one nectarine to quiet the hunger.

More than once, we’d bump into each other at the fridge — thief meeting thief. We would freeze, then silently agree: no words, no accusations. What happened at the fridge at night went into deep freeze.

By morning, the fruit was gone. To this day, no one has ever confessed.

Count to Ten

In the end, it always happened. After the hunger pangs, fatigue won out. My eyes closed, and my dreams featured all sorts of tempting things: a good cookie here, a piece of fruit there — and especially vivid, a whole quarter of a chicken or a bowl of cottage cheese.

In the morning, we received our official daily ration. Mother would send us — the boys to cheder, the girls to school — with a slice of the Israeli staple “black bread” from Berman’s bakery (it wasn’t really black, just made with unbleached flour), smeared with a generous layer of the ubiquitous chocolate spread to make it as tasty as possible.

But the time to eat it had not yet arrived. You had to wait until the ten o’clock recess.

For a little boy who hadn’t eaten since the afternoon before, this was a terrifying ordeal. I remember sitting in the classroom, eyes fixed on the clock above the rebbi’s head, following the second hand and counting every tick. If only today I could anticipate Redemption as I did then, waiting for the redeeming bell of ten o’clock — the moment I could finally put that slice in my mouth.

From the fog of clocks, seconds, and chocolate, a scolding voice broke in:

“Tell me, Aharon, can you repeat what we just learned?”

My eyes remained glued to the clock hand, which stubbornly refused to move. Only when I noticed 22 heads staring at me did I realize I had been called on.

The rebbi’s gaze was reproving.

“Tell me, are you even listening? Repeat what we just learned!”

Repeat what? Who? What? I felt like my soul was about to leave my body from hunger. My whole body shivered. A small inner voice teetered on the edge of tears: “Leave me alone! I’m hungryyyy!”

But shame and fear were stronger. I choked back the cry and endured rebuke instead. The rebbi claimed I had an attention issue and that this situation could not continue. On that last point, at least, I agreed.

My small body acted on survival instinct. My flushed face nodded in agreement, my eyes lowered in feigned attention — but they still flicked toward the clock.

Final countdown. Three… two… one.

Ten!

The rusty iron bell in the inner yard rang with an immense, harsh clang. Classroom doors flew open, and hundreds of children dashed to the sinks outside.

Ahead of them all, I stormed to the cup first with frantic energy — pushing, elbowing, gasping for air, and returning to the classroom triumphant. It took less than minute to swallow that chocolate-topped slice.

And one minute later, my tik was empty again. No food — only books weighing a ton.

Then came the hardest moment: the unbearable mix of hunger and envy. I looked around at my classmates’ tables, my little stomach twisting. The smells of oranges, tangerines, and apples filled the classroom as my mouth began to water. The shame of longing was unbearable. I wanted to beg for a scrap — one small section of a tangerine, the end crust of roll, the bottom of the yogurt container — but I was too proud.

I was Aharon, the best head, the sharpest kid in the class. I didn’t need anyone’s charity.

What’s for Supper?

I survived the ten o’clock breakfast. The next two lessons passed somehow. But by one o’clock, the growling started again. This time, though, there was nothing to look forward to. My tik was empty.

I hated the lunch bell. For me, it was the sound of daily gehinnom — a bell of smells and dishes I couldn’t touch, only see. To see, to be tempted, and not scream.

I desperately hoped it wouldn’t ring — but it did, every single day, like clockwork. One o’clock.

This time, I didn’t rush to the sinks. My hands stayed dry, my mouth dry, my heart dry. Around me, the feast continued. Children unpacked what to my little boy’s mind were royal meals — hotdogs, schnitzels, Tupperwares with rice and vegetables.

And there I sat, “king of the class,” silent and pretending. But my heart was burning. My eyes longed. And my stomach… oh, my stomach. The classroom became a torture chamber for body and soul. Five minutes later, the children ran out to recess, leaving the remnants of lunch behind. I scanned the leftovers, torn between survival and shame.

I always took the middle path: leftovers, discreetly. But often, there was nothing to take.

Somehow, this constant state of hunger didn’t affect my performance. I was a quick learner with the good head, always pulling top grades with minimal effort. Maybe that’s why the adults in my life never realized how much I was suffering.

When hunger grows, survival instincts awaken. Sometimes, when the teachers’ room was empty, I’d slip inside like a cat and stretch my little hand into the sugar canister, take out a handful, and chew on the grains. It didn’t satiate my hunger, but it helped temper the acidity in my mouth and my soul.

After the sugar gave me a small respite, all that remained was waiting for the final bell at five. Then I could return home — although not much awaited me there either, except for an empty fridge and the other half of the loaf of bread from the morning.

I would come home and prepare my little evening meal. I’d light the gas, slice a piece of bread, spear it with a fork and hold it over the flame for a few seconds. Then I’d spread on a bit of margarine. Scorched bread with margarine, day after day. That’s what my parents were able to give us.

Then, after moments of recovery, my stomach led me. I tried to engineer myself an evening meal. Here, connections mattered. Some friends’ homes were better, some worse. I always chose the ones who to me, at least, seemed like families of means. I’d knock on the door of a friend’s house. “I came to play with Moishy,” I’d say, and I would be invited in.

The truth was that Moishy bored me, but maybe, just maybe, his mother would serve supper — and include me. One visit was enough to mark that family as a food source.

But Moishy and his family had their own plans. Not every day was my lucky day. “Moishy went out,” “He’s not feeling well,” “We have a family simchah.” I smiled in shame, turned away, almost bursting into tears. I knew I would go to sleep hungry, as befitted the poorest family in Ramot.

At this point, you might think I’m exaggerating — but I promise you I’m not. I’ve even censored some of the more painful details. But soon, you’ll understand why I felt compelled to share such personal and difficult parts of my childhood.

Just Looking

Once a month, Rosh Chodesh meant a special holiday for our family.

On that day, all ten of us marched to the Eckstein home — a family of Gerrer chassidim who served as the monthly distribution point for Yad Eliezer. Into our food baskets went the staple products that the Ecksteins took straight from the pallets unloaded from supply trucks.

Oh, what joy! Ther were cleaning supplies, vegetables, oil, canned goods, rice and pasta. But for us kids, there was one treasure that surpassed them all: canned peach halves.

We skipped all the way back home and crowded around the canned fruit. Within 30 seconds of opening the can, it was gone. The pasta and rice lasted another few days, followed by the canned peas and hummus. And then it was over. Hunger returned.

Shabbos was a bit of a reprieve. We got to taste a bit of chicken in the cholent — beef was a fantasy. I would see the advertisements for the Chasdei Naomi chesed organization around the neighborhood with the slogan, “Mommy, you promised us chicken for Shabbos,” but I never understood the punchline. That was our life.

The pinnacle of the year was Erev Pesach. Abba received kimcha d’Pischa vouchers for the Birkat Rachel supermarket in Givat Shaul, the first retail chain to break the framework of the local grocery in chareidi neighborhoods. For me, entering the store was dizzying. Everything seemed infinite. We shopped carefully, but for the first time, a few “luxuries” crept in — things beyond fruit, vegetables, bread, and milk. Leaving the store with the cart, we felt like the happiest people in the world.

Vacation time — bein hazmanim — was the hardest for us children. The kids in the neighborhood would wait for buses to the separate beach, while we could only look at pictures of the sea and fantasize. Three weeks of boredom, while neighbors returned with stories and adventures. But we never asked, knowing our parents had no money and not wanting to cause them any more pain.

Abba couldn’t even afford bus tickets. I walked to cheder every day — a 20-minute trek each way, not an easy feat for a little boy on an empty stomach.

Midway between Ramot Daled, where my cheder was, and Ramot Polin, was Pinchas Greenwald’s grocery. Reb Pinchas is a warm, sweet Breslover chassid, who still runs the store from morning to night. Back then, the cartons of snacks, chocolates, and sweets piled outside shouted at me every morning on the way to cheder, and every afternoon on the way back home. Bissli, Bamba, potato chips, Egozi, Ta’ami, Mekupelet chocolate bars. It was beyond my power of choice.

At first, I only looked. Then I drooled in front of the chocolate milk bags in the refrigerator — one shekel ten agorot — which of course I didn’t have.

“Do you need help?” called the Arab worker. I lowered my gaze and slipped away in shame.

For the next few days, I heard a voice inside whisper to me: “Just one Bamba, Aharon. Pinchas won’t notice.” Hunger screamed while my conscience tried to outshout it: “Don’t dare steal! Aharon, what’s wrong with you? Have you become a thief?” Two voices, both loud, both terrifying, while I was torn between hunger and fear of transgression.

But one Thursday, I simply broke.

I entered the cramped little grocery, trembling all over. I crept to the last row of shelves, scanning every direction with survival instincts, making sure no one was watching. Pressing myself against the wall, I lifted my shirt and tucked a bag of Bamba inside.

Now I walked toward the exit, convinced no one had noticed. Near the cash register, my stomach betrayed me with the rustle of the wrapper, and the Arab worker — whose ears caught the sound — called out loudly:

“Hey, boy, what do you have there?”

I froze. My legs were rooted to the spot, my mind went numb, but I kept walking as if I hadn’t heard him, wanting to bolt like a missile.

“Hey, boy, what do you have there?” he shouted again. Silence fell over the grocery. My face burned red as a beet.

“Uh… umm… nothing,” I stammered, trembling all over.

Then I saw them — dozens of eyes staring at me. Neighbors, my father’s friends, people from the shul, and even some children from my cheder. All I wanted was for the ground to swallow me, for a lightning bolt to strike.

The Arab moved closer, yelling, “Hand it over!” I lowered my gaze, paralyzed, trying to escape the stares piercing me like needles.

“Hand it over right now, or I’ll call the police!”

Panic overtook me. Police, handcuffs, prison, parents knowing, cheder knowing. Better death than life.

I pulled out the Bamba and handed it over. The Arab relished his victory, while the air was thick with silence.

Then Pinchas appeared. Four seconds and he understood. He roared, “Mohammad, roch min hone — get out of here!”

Pinchas handed me back the Bamba and tucked a few chocolates into my hand. Whispering, he said, “Don’t pay attention to him. He’s a real mean guy. But next time, please don’t take without permission.”

I gave my word and ran from the grocery as fast as I could. Legs shaking, I continued toward the cheder, but as I stood in front of the iron gates, I knew what awaited me: the children who had seen everything.

Unable to face the whispers and disgrace, I turned toward the kever of Shmuel Hanavi. In those days, Ramot ended just a hundred meters beyond our cheder, and beyond that was the Jerusalem entrance checkpoint. Even the soldiers looked a bit surprised to see an eight-year-old crossing alone.

“Where are you going?” they asked.

Gathering my courage, I said, “To the kever of Shmuel Hanavi.”

“Okay, go ahead,” they replied.

All day I sat at the tomb, unsure of how to pass the time. The place was empty, except for an old Sephardi man reading Tehillim and Zohar aloud.

I took a Tehillim and prayed in the words of a child, just like I always read in the sippurei tzaddikim books: “Ribbono shel Olam, I, Aharon ben Hadassah, beg You, give me food like other children, let me be full, let me have cooked food and cut-up vegetables. I would be grateful for a daily clementine and an apple. I am ashamed to ask friends, and I don’t want to steal from Pinchas. But I am so, so hungry, and I know that if You want, You can send me food immediately.”

Tears poured down my face — tears of a child who was king of the class, a bookworm, an avid learner, but also a child who had known nothing but hunger and poverty.

Meanwhile, a family had come to celebrate an upsheren and was handing out platters of cookies, nuts, raisins, and tea. I had my own little party, and then counted the minutes until five. But before I left, I added another prayer: that the story with Pinchas would not reach my parents.

I returned home in fear, but it was also the first time I felt the power of tefillah. My parents hadn’t heard a thing. And as it was Thursday, in the evening the fruit delivery would arrive, offering a few slices to quell the hunger. Friday evening meant finally having challah with hot fish.

Straight from Heaven

Shabbos passed, and then it was Sunday again, which meant that I hadn’t had anything to eat since Seudah Shlishis the day before, except for the one slice of bread and chocolate at ten o’clock.

That afternoon, the rebbi called me over. He pointed to the coat rack at the back of the room that had collapsed under the weight of all the backpacks, and asked me to take it to the custodian Ephraim’s storeroom so he could fix the hooks.

Ephraim’s storeroom was at the back entrance of the cheder yard. A gloomy, windowless place smelling of mildew, crammed with every kind of junk, yet Ephraim was the undisputed ruler of this motley kingdom.

I opened the creaking door. Shelves overflowed with spare parts, nails, screws, hooks, cleaning supplies, broken chairs and tables awaiting welding, bars, toilet tanks, floor tiles, broken faucets, rusting sinks. A single dim bulb lit the space.

“Ephraim,” I called into the storeroom.

A muffled voice replied: “Aha, motek, what can I do for you?”

“They sent me with a broken rack to fix.”

“Come in, motek, come in,” he shouted.

I hopped over piles of junk and stepped inside, rack in hand. Ephraim sat in a welding apron, repairing some broken handles, with what looked like a thousand keys hanging from his belt.

“Sit down, motek, I’ll be with you in a minute,” he said.

I sank into a worn sofa, watching sparks flying from the welding. And then, it struck me. The smell. Cooked meat with rice and peas. My stomach twisted. I felt dizzy. Weakness spread through me. My eyes fixed on the source: an orange plastic plate among the spare parts, covered by another plate.

“Okay, so what’s the story with the rack? Hey, are you listening?” Ephraim said, shaking me out of my reverie.

He glanced at the shelf and realization dawned.

“Motek, are you hungry?” he asked softly.

Ashamed, I lowered my eyes.

“Come, kapparah, sit down and eat,” he said, handing me the plate. It was hot and full.

I devoured it in a minute, in a frenzy. I barely looked at him. “Ephraim, thank you,” I whispered.

He was stunned. He understood what an entire team of educators had not.

“Motek,” he said gently, “if you want, you can come here every day. I will give you food.”

“Every day?” I asked, almost hallucinating.

“Every day,” he said, escorting me to the door. “What’s your name?”

“Aharon.”

“Great. Make sure to come tomorrow, too,” he said.

When cheder was over, I took a detour on the way home, instead going back to the kever of Shmuel Hanavi. Pressing my head against the gravestone, I cried and cried, whispering, “Ribbono shel Olam, thank You for the angel Ephraim, sent straight from Heaven.”

Caught in the Middle

Life has a way of instantly changing.

Every day, Ephraim the custodian would leave our cheder for his other job at the Chabad cheder next door. Only an iron fence separated the two buildings, and Ephraim was custodian for both.

Unlike us, the Chabad boys received a hot, catered lunch. At the end of each meal, Ephraim would collect the leftovers, place them on the orange plastic plate, cover it with another plate, and put it on a shelf in his storeroom.

And every day, before the end of lunch break, I would slip into the storeroom, where Ephraim was waiting for me. In the three minutes before the bell, I would devour the contents of the plate and return to class, full but also a little frightened. Because there was a strict rule, that no one was to approach the custodian’s private space without permission.

Yet Ephraim’s food was like mahn from Shamayim. He forbade me to thank him: “Motek, no unnecessary words. Everything is from Hashem, yitbarach Shemo.” In truth, that made it easier emotionally. All day I dreamed of Ephraim and his plates. They gave me hope and strength to survive.

And so it went for several years — a secret arrangement between Ephraim and me.

But then an accident happened.

Ephraim cut his knee with a box cutter and had to be taken away in an ambulance. Everyone worried for him — but I worried for myself. I felt my world collapse. Hunger would strike again, and all the feelings I had struggled to forget came rushing back. I prayed for his recovery, but most of all, I begged that my food pipeline would return.

After a week that felt like a nightmare, my prayers were answered.

“Ephraim, I waited for you,” I said. He smiled. “Believe me, motek, I didn’t stop thinking about you, how you were managing….”

But then something else happened, and it had nothing to do with Ephraim.

One day I was a bit careless, and I was caught red-handed. The principal saw me entering Ephraim’s storeroom and locking the door behind me. It was definitely a suspicious sight, and the principal was duly alarmed. Students were forbidden to speak with maintenance staff or enter their personal work spaces — and justifiably.

That same day, Ephraim was warned that I was not to enter the storeroom. Poor Ephraim feared for his job, while I feared for my survival.

He was in a dilemma. He couldn’t tell the principal about the food he had been giving me — he was basically syphoning off leftovers from another cheder without permission. And so he assured the principal that he would sever all contact.

And he did. I felt as if a ton of stones had fallen on my head. My dependence on him had become obsessive. He was my oxygen. I tried to make eye contact in the yard to hint at our connection, but he avoided my gaze. He was a family man, protecting his livelihood.

But deep down, he knew he was also my lifeline. One day, after a week of disconnection, he whispered as he passed me: “Aharon, you know they’re watching me. From now on, I’ll leave it for you on the window.” And he disappeared.

I was thrilled, but I also knew I had to maneuver carefully. I no longer had a hidden place to eat.

True to his word, every noon he placed the orange plate on the storeroom windowsill. But during lunch break, I couldn’t touch it. The yard teemed with children and staff, and the storeroom was locked.

Every afternoon I had to invent an excuse to leave the classroom. In the two-minute bathroom break, I would fly to the windowsill and gulp down the food that Ephraim had left for me. The yard was empty then, and while I wouldn’t be spotted by students, I was always scared that a staff member would pass by. I was mainly afraid for Ephraim, that he would be caught and fired from his job. He was, after all, risking himself for me.

But there were also days when I couldn’t finagle an excuse to leave, or the rebbi wasn’t in the mood to let me “go to the bathroom.” Those days were torture — I was starving, while all that food was lying just a few meters away.

Sometimes I would wait until the next recess ended and everyone went back into the classrooms, then pounce on the windowsill like a stray cat, devour the contents of the plate, and return to class five minutes late, risking getting scolded or punished. But believe me, no punishment can compare to an empty stomach.

I Believe in You

Ephraim’s meals continued for the next five years, until I turned 13 and finished cheder, moving on to yeshivah ketanah.

I’ll never forget our last day of class. A day of farewells and new beginnings. Friends who had walked with me for ten years were leaving for different paths.

But truthfully, I didn’t really care too much about parting from friends, teachers, or even the principal. I cared about Ephraim, the holy custodian, my angel who had seen me when no one else had.

When the final dismissal came, everyone left with their backpacks full of books and other paraphernalia. The staff filled the yard, and we passed before them like a parade. And then my eyes found Ephraim, standing near the principal.

I approached him. The principal stiffened, but I had nothing to fear now — in another minute I would no longer be a student here.

“Ephraim,” I said, “you should know that I owe you my life. I don’t even have words to thank you.” My body trembled, and he, too, was visibly moved.

The principal looked as us, stunned. “What?”

“Ephraim gave me food every day for years,” I said. “I survived only thanks to that windowsill,” I added, pointing to the storeroom window behind them.

Suddenly, comprehension dawned on him. “What? The whole story between you was… food?”

We both nodded.

The principal drew me close, hugged me, and kissed my head. “Aharon, forgive me,” he whispered, as tears filled his eyes. I also cried. I’d been in this cheder since I was three years old, and I had never once seen him shed a tear. Never.

We wept together, and Ephraim watched from the side, realizing that his secret had been revealed, but proud of his great mitzvah.

“Dear Ephraim,” said the principal, “in Aharon’s name and mine, I want to thank you. And also to ask you for forgiveness. If only I had known….”

Holy Ephraim shook my hand. “Aharon, motek, be strong and stay in touch. You are going to rise to great heights. I believe in you.”

I waved goodbye, and deep inside, I knew it was truly farewell.

The Need to Feed

Life went on.

I moved to a yeshivah in Bnei Brak, then went on to yeshivah gedolah, married, built a home, had children, and life began to flow.

But what can I tell you — years of hunger never truly leave you.

For the last 30 years I’ve struggled with emotional eating. Every time I see cooked food, I feel flooded by a rising survival instinct. In my various roles in media and journalism over the last two decades, I’ve met thousands of people, interviewed hundreds, seen countless hardships. And yet, the one suffering I still can’t bear is that of hungry children. Hearing about poor families unable to feed their children clutches at my heart.

Today, more than three decades later, the huge networks of food baskets, vouchers, supermarket refill credit cards and restaurant-style soup kitchens save families from disgrace, and come before everything. I know this because I lived it.

Sometimes, late at night, I’ll find myself near a still-open bakery in Jerusalem, when I encounter someone outside, asking for a handout of something to eat. And each time, I feel the old pangs. I can tell by the faded coat, torn sneakers, messy peyos, a once-black yarmulke and a collar that’s even blacker.

I never give money. Instead, I say, “Come in with me,” and start piling baguettes, bourekas, cola, and cakes into a bag. In those moments, I become little Aharon again. My wife is used to it by now, this compulsion I have to feed the down-and-out.

One day, when we were driving together and I stopped at a gas station, where I spotted one of those hungry souls and immediately filled up a bag of food for him, my wife broached the subject. “Tell me,” she asked gently, “what’s your story with all these miskeinim in front of Nechama’s bakery or at the gas stations? Why do you feel that you need to feed them?”

And so, finally, I shared the story of Aharon the child — who went to bed and woke up hungry, who thought only of food and how he could get a decent supper — and about Ephraim, the holy custodian who saved my life. We cried together.

She understood, at last, the depth of my past, my drive to ensure that my children never lack food or other material amenities. And she also heard about the anonymous hero who saved me.

“Aharon, why didn’t you tell me until now?” she asked.

“Because I was ashamed,” I whispered.

After a moment, she asked thoughtfully, “Aharon, did you ever think of meeting Ephraim again, this time as a grown man?”

I paused. “After repressing all this trauma for so long, to bring it up again now? Why? For whom?”

“For your soul,” she answered. “To meet your past and make peace with it, to show gratitude 30 years later.”

I promised to think about it.

Search for My Savior

For six months, I wrestled with the decision. Finally, I resolved: I would find Ephraim and close the circle.

But where could I find a man whose last name I never even knew?

I began phoning classmates, some of whom I hadn’t spoken to in three decades. I felt like a ghost rising from the grave. But like me, no one knew Ephraim’s last name.

I contacted the rebbeim as well. Some of them, the elder ones, had passed on, while some others had no recollection. Finally, I called the principal. He remembered me instantly, and after some polite conversation, I asked, “I’m looking for Ephraim’s number.”

Silence. He understood immediately. “Expressing gratitude is very important,” he said warmly, but the only detail he could give me was Ephraim’s last name: Avichzer. Beyond that, nothing.

“He worked with us only eight years,” he explained. “Shortly after you left, he left the cheder and became a renovations contractor.”

I was moved to tears. Eight years — that meant Ephraim had been sent to me from Heaven, special delivery, and once he finished his mission he disappeared.

For months I searched for Ephraim Avichzer across the country, without success. Someone told me they thought he’d moved to Tzfas; another said he heard he was in Manchester. Someone else reported that he was living in Toronto, or that he’d recently moved to Rosh Ha’ayin. But in all those locations, nothing turned up.

I began to despair, doubting whether he was even still alive.

Then, the breakthrough. Just a few weeks ago, a friend told me he heard that Ephraim had moved into his late father’s apartment in Jerusalem, right in the middle of Geula. He’d been caring for his father for years, until the recent petirah. I didn’t waste any time. Before losing my resolve, I hopped into a cab and headed for Rechov Malchei Yisrael.

I reached the building I was told about, looking at doors, but the apartments were all divided into small studios for offices or small businesses. And then I reached the roof. Nothing suggested anyone lived there — until I saw a hidden corner that shocked me.

Boxes, nails, screws, hooks, broken furniture, and piles of door handles — Ephraim’s storeroom. Nothing had changed. A man carries his homeland within him.

I knocked. Heavy footsteps approached. The door opened. There he was, beard now white, smiling as always. “Shalom,” he said, cheerful and curious.

I was speechless. Words failed me.

“Ephraim?” I asked, though I knew it was him.

“Yes. Who are you?”

“My name is Aharon.”

“Aharon?” he asked, trying to place me.

“I came to thank you,” I said.

“Me?” he blinked, confused.

“Yes, for the food you gave me in cheder, when I was a little boy.”

Three seconds later, the penny dropped. “Waaah, I don’t believe it!” he shouted, hugging me. I trembled in his arms, little Aharon reborn.

“Don’t cry, motek, don’t cry,” he said, kissing my head and handing me a tissue. “What can I give you, Arak or water?”

But before I could sit down, I had to ask the question I carried with me for 30 years:

“Ephraim, why? Why did you decide that day in the storeroom to take care of me? Hundreds of children studied in the cheder. Why me?”

And ever-sweet Ephraim answered me in two words: “Your eyes.”

He continued, “When you came into the storeroom and your eyes locked onto the plate, I understood everything. Without a word, I knew. In that moment I decided in my heart: I will take care of this child.”

We spent an hour together, reliving memories. I told him about my global search, my longing to see him, to say thank you.

Ephraim, who had devoted six years to caring for his father, was now living in in the center of Jerusalem. Yet he wasn’t ready to rest. He has an electric bicycle with a trailer, and every evening he collects fruits and vegetables from the shuk or that the greengrocers had discarded, bringing cartons of produce for free distribution to avreichim.

I left Ephraim’s home with a decision: Despite shame, despite years of private suffering, I would publish this story — my story with Ephraim.

I lift my eyes to you, dear reader, and beg you: Look around. Look out for the little and hungry Aharons. They might be your neighbors, or the children taking too many cookies at the kiddush, or orphans, or children of broken homes. Transparent children wandering among us unnoticed.

Do not ignore them. Lend a shoulder. Offer help. Be the angel to one child. Save him — and save yourself in the process.

And finally, one parting blessing:

May G-d make you like Ephraim.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1081)

Oops! We could not locate your form.