China Bridges the Gulf

Iran and Saudi Arabia reestablishing diplomatic relations via a Chinese-brokered agreement is disturbing on many fronts

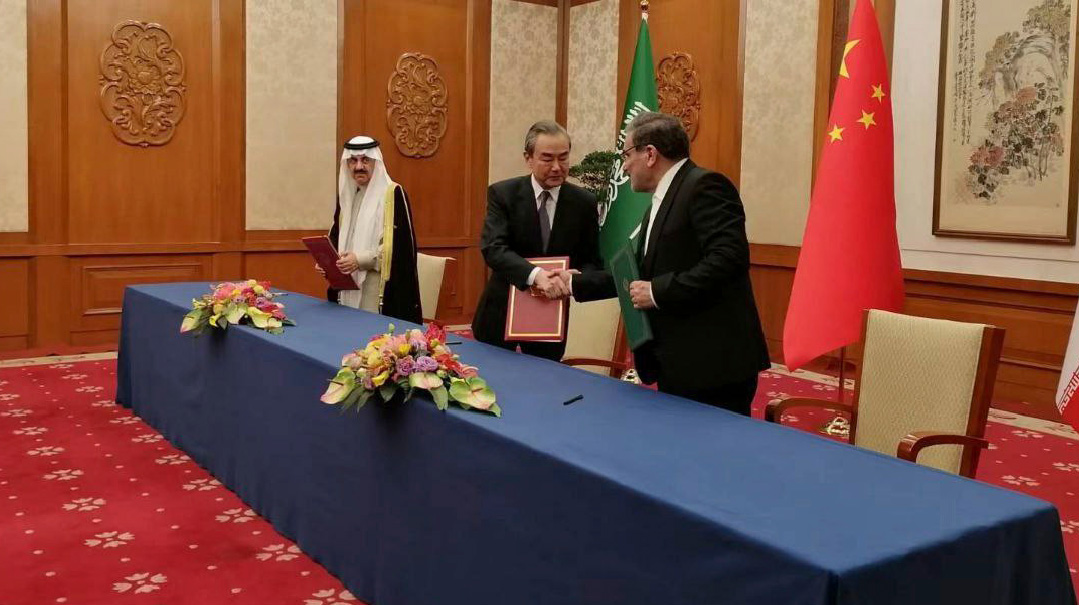

Photo: AP Images

Three years after the Abraham Accords breakthrough that brought normalization deals with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan, the announcement that Iran and Saudi Arabia are reestablishing diplomatic relations via a Chinese-brokered agreement is disturbing on many fronts.

Leader: Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman

Status: English-speaking modernizer, open to peace with Israel

Lesson: The surprise agreement with Iran is the result of a perceived American regional exit

How the deal will impact the normalization talks between Israel and Saudi Arabia is yet to be seen, but on a tour of the Gulf in recent weeks, I picked up some early warning signs.

In conversations with multiple leaders, I heard a message of concern at America’s apparently diminishing commitment to the region. I also became aware of a lessening in Gulf leaders’ fervor about combatting Iran.

The Saudis know that diplomatic agreements won’t change the stripes on the Iranian tiger, but America’s shrinking presence in the region has enabled others — notably the Chinese — to step in as a broker, extending their influence in the region. But we should not overstate the implications of this arrangement in the longer term.

What looks like an achievement for Tehran and Beijing is a setback for the wider regional architecture that I and many others have spent years advocating. That plan would place Israel at the heart of a pro-Western bloc of states stretching from the Mediterranean to the Gulf and Asia.

The first major public step in achieving that vision was the signing of the Abraham Accords under the Trump administration. That breakthrough was part of a long process that we at the Conference of Presidents and others contributed to with civilian diplomacy — the behind-the-scenes influence that American Jewry can exert.

I started visiting the Gulf in the ’90s, first in Qatar, then about a decade ago establishing links with the UAE, and five or six years ago openly with the Saudis.

But, in fact, there has been a decades-long history of contacts, and I always believed that the Gulf states — despite the tangential roles that they had played in conflict with Israel — held greater potential for ties with Israel.

That potential is beginning to unfold in earnest. In the United Arab Emirates, it’s now safer to wear a yarmulke than on the streets of Paris or Berlin. When dozens of Jews sit in a kosher restaurant at a mall in Dubai, no one bats an eyelash.

The opening of the Gulf States has been led by Mohammed Bin Zayed, known as MBZ, the ruler of Abu Dhabi and president of the UAE. I have met him often over the years in a deli restaurant in Abu Dhabi, indicative of the warm relationship he sought to establish.

In an effort to promote tolerance, the Emiratis have introduced Holocaust studies, and are changing their school textbooks so that the narrative on the Israel-Palestinian conflict isn’t slanted against Israel or Jews.

When I first met MBZ, I found him to be very analytical and thoughtful. I told him about the long Jewish history in the Gulf. In the Middle Ages, there was a significant Jewish presence on the island of Hormuz, off the coast of modern-day Iran, which was a waystation along the trade route between Europe and the Far East.

I visited the Emirates a few weeks ago with a COP delegation and attended the opening of the Moses Ben Maimon synagogue, which, alongside a mosque and church, make up the Abrahamic Family House, a government-sponsored interfaith center in Abu Dhabi. The shul — which contains a mikveh — is an amazing sight.

It shows how far the Emirates have come in just a few years, given that a short time ago, the government only permitted a synagogue to operate in an unmarked private villa.

MBZ was fulsome in his commitment to the Abraham Accords, which had led to this boom in open Jewish life in the region, but he expressed concerns about the diminishing American role in the region, as well as about “instability” in Israel.

And although the Palestinian issue is no longer the central focus of Israel-Gulf relations, it still has traction on the street — particularly when there are flare-ups between Israelis and Palestinians.

Near the Emirates is the still-elusive prize of the Abraham Accords — Saudi Arabia. Even though the UAE’s decision to normalize relations with Israel would not have happened without the blessing of its giant neighbor Saudi Arabia, a formal agreement with the Saudis would bring the legitimacy of the leading Sunni Muslim state to the accords.

About 20 years ago, then-Saudi ambassador to Washington Prince Bandar became a close friend of mine. He spoke at the Presidents’ Conference and we maintained an open dialogue about Israel. He even brought the foreign minister to meet with me.

Another ally was Mohammed Al-Issa, a Saudi minister and secretary-general of the Mecca-based Muslim World League. Al-Issa is a global voice in the battle against extremism, who has visited Auschwitz and spoken of the need for Muslims in the West to integrate with their host countries.

Fast-forward to a few years ago, and I began to meet with Saudi Arabia’s young crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman. MBS, as he’s known, speaks excellent English, and wants to modernize his society, weaning it off oil.

As part of his vision to transform Saudi society, he has planned a massive, futuristic city called Neom by the Red Sea, at an estimated cost of $500 billion. Even though it’s still largely on paper, he speaks of the city in very real terms, and wants Israeli technology to make it happen.

I mentioned to him that if Saudi Arabia were to follow the Emirates’ example where there is a boom in kosher restaurants, then Jews would flock to the country. So I suggested we open a kosher catering business.

“But I have to worry about halal,” he said.

To which I replied that while kosher consumers can’t eat halal, kosher certification covered Muslim religious law as well.

“We can call it Halal-sher,” I told him, and he said he wanted to give it some thought.

The Saudis still want to see a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But unlike his father King Salman, who views the Palestinian issue as a major impediment to Israeli-Saudi normalization, MBS no longer wants progress with Israel to be held hostage to the PA, which he views as corrupt, a “kleptocracy,” as many call it.

If so, why did the Saudis come to an agreement with Iran, seemingly putting on hold the progress that’s been made toward a deal with Israel?

The Saudis and others perceive a waning American commitment to the region. One of two US Navy aircraft carrier groups has been withdrawn and switched to the Asia-Pacific region to confront China’s buildup. When Iranian proxies attacked the Abqaiq oil fields in 2019 — taking massive amounts of production capacity offline — the US did not respond.

They see Iran moving ahead with a nuclear weapons program and the response of the West is weak at best. The US sanctions help but are not sufficient. Iran's economy is very weak and they are susceptible to increased pressure.

China’s move to broker the Iranian-Saudi agreement took many by surprise, but for those watching the region, Beijing’s entry to fill the void that America’s perceived disengagement left wasn’t so surprising.

The rise of China as a rival to America is certainly a major challenge, but countering their military buildup in the Pacific and thus leaving the Middle East to the encroachment of Russia and China won’t make America safer. The Straits of Hormuz remain the transit point for almost 30 percent of the world’s oil — including 60 percent of the West’s supply — and so maintaining open shipping lanes is a core American interest.

In a world of American retreat, Gulf leaders see Israel as part of the solution — an unsinkable aircraft carrier in the area.

But despite Israel’s heft and the ongoing exercises in which Israel and the US simulate an attack on Iran, in the Middle East, perception creates reality, and leaders act based on these assessments even if the facts of hard power haven’t changed. One outcome may be the Saudi move to reach an accommodation with Iran.

What does this mean for normalization with Israel? We don’t know whether the Iranians have conditioned rapprochement with the Saudis on an end to the warming ties with Israel. Some speculate that it will actually make a breakthrough with Israel easier.

A lot depends on the Americans, who have received a list of Saudi conditions for proceeding with normalization with Israel.

But one thing is for certain: for any breakthrough to happen between Israel and the Saudis, negotiations need to be kept secret — something that Israelis, historically, have at times not been good at.

Sometimes information is leaked for political reasons, from elements who are hostile to the moves, and at times for less benign reasons.

I know multiple US amd Israeli officials who bypassed their own embassies and used our channels to talk to different actors because they were afraid of leaks.

If an opening with the Saudis is to happen, it will have to be done quietly, like the Abraham Accords, which didn’t leak.

Last week’s deal was dismaying for another reason: because it drove a wedge in a bigger plan to establish American and Israeli interests in the region. While the diplomatic focus is on the Gulf’s heavyweight, Saudi Arabia is just one link in a much larger regional architecture with Israel at its center, which can serve as a counterweight to the rise of China in the region.

Over the last decade, the Chinese have used their economic muscle to edge into the Middle East. Their Belt and Road Initiative — a massive system of infrastructure projects that span much of Asia and Europe — is designed to draw countries into China’s sphere of influence and create debt-traps that hand key facilities like ports to China.

I’ve shared a vision of an alternative Israel-friendly regional partnership that would promote peace, economic development, and security, as well as act as a regional counterweight to China’s influence. From America to the Middle East and Asia, many parts of this bigger model have fallen into place in recent years.

Central Asia was an early port of call. Three decades ago, I realized that the post-Soviet states of Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan — although majority Muslim — were low-hanging fruit as regards the potential for peace and relations with Israel.

Many people don’t realize that for much of history, Jews were treated far better in the Islamic world than in the Christian world. In Central Asia, leaders assert with great pride that there has not been anti-Semitism in the 2,600-year history of the Jewish presence there.

The Central Asian countries are places with ancient Jewish communities — some two millennia old — and no vestiges of anti-Semitism, as I learned firsthand when visiting Samarkand, Uzbekistan in the ’90s.

There were Jewish schools there, and the students came out and danced in the streets waving Israeli flags. I advised the members of our delegation to wear baseball caps outside given that it’s a Muslim country. But then the police chief heard about it and said to me, “There’s no problem — you can wear a yarmulke and no one will even comment.

We also met Jewish university students who were openly identified and did not experience anti-Jewish feelings either. When I asked them whether they encountered anti-Israel feeling on campus, they laughed. “They can’t stand the Palestinians around here,” they replied.

Peace deals with the Central Asian republics give Israel a foothold in Asia, and Israel now has good ties with a massive Asian power, India. South Korea also enjoys extensive trade relations with Israel.

While the breakthroughs in the Gulf have received the most attention, Israel’s gains around the Mediterranean are also noteworthy.

To Israel’s south and west, we envisioned a Mediterranean Initiative drawing together Egypt and Israel with Greece and Cyprus as the core of a regional coalition. Years ago, I shared the idea with Egypt’s current president Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi.

“I’m in,” he said, “and I’ll bring the Gulf states with me.”

That was long before any talk of the Abraham Accords. The Mediterranean Initiative is alive and progressing, with Morocco and other countries now linked in.

For much of the 20th century, Israel and Greece — a NATO country — had strained relations. But in 2008, the two countries grew far closer as they partnered on natural gas extraction, and a pipeline via Greece to send Israeli and Cypriot gas to Europe.

Today, Israel is a hub anchoring America’s presence in the Middle East, from allies Greece and Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean to the Gulf.

Israel’s place as an anchor in the region has been recognized by its recent transfer from the responsibility of the United States’s European military command to CENTCOM, responsible for the wider Middle East.

All of that means that an assessment of Israel’s position in the region must take into account far more than Iran and Saudi Arabia. Israel is both a technological and military powerhouse, and key to a regional partnership underwritten by American power. The historic Juniper Oak exercises, the largest US-Israel joint military operation ever, underscores the continuing US-Israel partnership and Israel's central role.

Still, these two countries remain key.

The Emiratis are confident about their decision to normalize ties with Israel, but at the same time they feel exposed and want others to join them.

We need to see broadening and deepening of both civilian and governmental ties, so that there are far more Emiratis coming to Israel, and that business and tourism networks expand to anchor the government-to-government contacts.

The lesson of the Saudi deal with Iran is that what doesn’t go forward can go back, and a leadership change in the Gulf could reverse progress on vital peace deals.

Citizen diplomacy of the type that we practice can make breakthroughs, but only governments themselves can close the deal.

Azerbaijan and Amalek

During our visit to Azerbaijan, there was an incident that I’ve never forgotten.

Our delegation was in the capital Baku over Shabbos, and we made a minyan at our hotel with the area’s Chabad shaliach, during which we honored various locals with the aliyos.

It was parshas Beshalach, and we gave acharon — which describes the war against Amalek — to a local man.

When he finished, the shaliach turned to me in shock, and said, “I don’t believe what just happened.”

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Do you know who this man is, who just finished his aliyah describing the destruction of the Jewish People’s enemy?”

“This man is Stalin’s grandson.”

Pyramid Scheme

Osama El-Baz, an Egyptian diplomat and key presidential advisor who died in 2013, was Cairo’s prime go-between to Israel, the man who negotiated the terms of Sadat’s visit in 1977. We became good friends, and he spoke out very strongly in condemnation of Hamas.

El-Baz proved very helpful when we took a Conference delegation to Egypt in the ’90s.

On that occasion, one of the delegates had to say Kaddish, so we had a minyan in front of the Sphinx and the pyramids — a sight that can’t have happened too often since the days of Yetzias Mitzrayim.

El-Baz tried to come to the rescue when we had a food emergency. We’d taken along a three-day supply of food for the delegation on our flight from Israel, but when the containers were unloaded at the airport, they were left on the tarmac for hours in the boiling 100°F heat. All of it was spoiled

I told Osama El-Baz, who replied, “Don’t worry, I remember what you need from the Jewish friends I grew up with. I’ll take care of it.”

I assumed that the Sheraton Hotel where we were staying had a supply of frozen kosher meals, and so I relied on him.

But later that day, we sat down, and after bringing us pita, hummus, and vegetables, they brought out elaborate platters of fresh lamb and meat stews.

“Where’s this from?” I asked Osama El-Baz.

“We eat halal, which is the same as kosher,” he replied proudly.

“Thanks so much for your help, but it’s not, exactly,” I had to tell him — and we ended up eating the frozen meals anyway. We got another shipment from Israel a day later.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 953)

Oops! We could not locate your form.