Care to Connect

| January 24, 2023When this email landed in our inbox, it struck a chord with everyone who read it. The ensuing conversation evolved into this piece

Icome from a typical, balabatish kind of family who always emphasized frumkeit.

In high school and seminary, I grew a lot on my own and developed an extremely close connection with Hashem. When I came home from seminary, davening became a bit harder for me, with my new schedule of college and work. But I always davened.

Then I got married, and it got a bit harder. But I always davened. Then I could barely get out of bed for the first few months of my pregnancy — and I never davened. Nothing.

That just started my routine of no davening. At all. I’ve since had multiple children, a few years have passed, and davening is still not a part of my routine. I’m married to a very serious ben Torah who’s learning in kollel and who doesn’t seem to be leaving it any time soon (if at all). I look very frum and I act the part, I live simply in Eretz Yisrael so that we can live a Torahdig life, and I’m proud of all this… but as to davening, nothing.

I feel I have lost my connection with Hashem. I can’t reach out to anyone, can’t even tell my husband or friends. Nobody would even believe me. Why does everyone around me seem to make it work, davening twice a day, even with kids and work and everything else? Even on days that I have nothing better to do, davening just doesn’t come to mind. Every now and then I get inspired from something, and decide I’ll start with brachos. Just say brachos this week. Day one, it works. Day two, maybe. Day three, I don’t even remember that I wanted to do this.

I feel totally lost in my connection, and yet, I want to have it so, so badly. I teach my kids all about it! But I just can’t seem to find it for myself.

It’s not that I forget. Sometimes I remember that I want to say brachos, but since I’m not really interested, I don’t carry through. And on those days I feel motivated to daven more of Shacharis, I start with brachos, and then feel depleted at the end. Like, I just don’t want to say any more. I did enough.

I’m a “normal,” happy young mother, and I can’t imagine that I’m really the only one with this problem. But I can’t open up about this. I’m too embarrassed.

I would love to hear from other people — who’ve been there, who’ve been through it — who can tell me how I can get past this.

How I can recapture that lost connection?

Search for Serenity

Shevy Levine

The road to motherhood feels like one long, extended prayer. Even throughout those days when I can’t bear to look at the pages, one tefillah or another is always on my lips. There is so much to ask for, such acute desperation and searing awareness. There is only Him. We need Him. It’s that simple, really.

And then, at long last, Baby comes along — and our world turns around in the most beautiful and wondrous of ways. We are so ready, so eager to fall into parenthood. Every aspect of motherhood is an adventure, and I celebrate each one. Late-night cuddles, first sniffles and fevers — I am determined to embrace every second. And well, if my tefillah takes a backseat, isn’t that just another facet of my newfound role? It’s almost a badge of honor — sooo busy, no time to daven — just another sign that I’ve finally arrived.

True, Mizmor l’Sodah is always on my lips. And the tears I shed at lichtbentshen can put any Yiddishe mamme to shame. As for formal tefillah, I console myself by throwing my efforts into other areas of avodas Hashem. A beautiful Yom Tov table. Supporting my husband. Chesed. Motherhood, of course.

But a hole begins to surface where connection once lived, and a sense of searching takes root where serenity once grew. I start feeling unmoored, but I have every speech on motherhood running a counteroffensive. Every halachic discourse on women and tefillah can explain my newfound approach. I quiet the voices, distract myself, and keep moving on. And yet....

I sometimes wonder why new habits are considered hard to form. Some are, I suppose. But clearly, some aren’t. Time passes, and before I know it, I’m hardly davening at all. I blush when my husband shares a Torah thought at dinner, and I can’t recall if I’ve said brachos before I comment. I’m not proud when I realize my siddur was left in the car for a couple of weeks, and I didn’t notice. I hadn’t planned for this change, but it’s here all right, and at this point, I’m too far in to know what to do.

Time passes. My baby grows. Another one comes along — and then, incredibly, another. My hands are full, and I’m busier than ever. But we’ve also reached a certain predictability within the chaos. My littlest begins sleeping through the night, my oldest is starting kriah.

My kids are growing, and their needs are too. With time, I sense a shift. Subtle, but gnawing, and growing slowly with each passing day. If I don’t daven for them, who will?

But growth born of guilt is hard — no, impossible, to sustain. Whatever I manage to daven is never enough, could never match up to the teary-eyed bubby I have pictured in my head. The unfocused Shemoneh Esreh that I eke out some days seems like more of an embarrassment than saying nothing at all. And is it even bekavodig to daven in a nightgown? taunts a little voice in the back of my head. Whatever I manage to say and do seems so pathetically small, so paltry and futile in the endless dark hole of our needs.

It’s not enough. But still, I try. I sit down with my husband, explain to our rav. I don’t feel proud asking for the barest commitment — what is the absolute minimum I could say? And yet, I realize, this is me. For now, for today.

I’m starting here. Not for the tzaros of today, and not to prevent the possible woes of tomorrow. I’m doing this for me, because I need Him, in the plainest and most profound way. And how can you possibly connect with Him if you don’t even speak?

I start. I stop. I start again. Brachos, Shema, Shemoneh Esreh. Ideally, all three. Sometimes just one. And on those days when I can’t can’t can’t, I push myself to just say the words “Shema Yisrael, Hashem Elokeinu Hashem echad” with as much focus and strength as I can, for the sake of bringing Hashem into my day. I let go of what should be — those lofty, inspired visions of instant connection and heartfelt pleas. Instead, I focus on what could be. I could read the words. I could do so consistently. Above all, I could try.

I distance myself from hopes of heart-gripping breakthroughs and inspirational accomplishments. I let go of expectation, and the 101 voices in my head demanding, Seriously, is this the best you can do?

I find sparks of motivation in the smallest of things as my heart begins to feel. My son brings home a bookmark with a picture of himself, and I tuck it into my siddur so I can peek at it and see him cheering me on. He loves that. I love it too.

My commitment grows stronger. What was always a chore is now at times a treat. A particular focus on Bareich aleinu the morning before a big work contract closes. A heartfelt birchos haTorah the day of a parshah siyum. I find myself leaving work early to get in a Minchah one particularly trying afternoon.

Growth is hardly linear, and most days are still dry and uninspired. I miss a day. Sometimes two or even three. I go two weeks straight without Shemoneh Esreh, then find myself saying it twice in a day for four days in a row. The length and nature of my tefillah wavers, but my commitment is steadfast. And what have I committed to, after all? Only to try, honestly and truly. Nothing more and nothing less. And slowly, slowly, I change.

My oldest is now old enough to daven. I watch him one Shabbos morning, as he caresses a Tehillim, eyes aglow. The words are still laborious for him; he stammers them out, sound by sound. He doesn’t seem bothered — not by his pace, nor his lack of understanding. He’s talking to the Eibeshter. He’s trying his best. I watch and I wonder if perhaps he understands best of all. I watch and my heart soars, a prayer forming on my lips. I daven for him, of course. After all, I’m his mother.

Five Minutes, Fifty Percent

Rikki Schultz

IN

preparation for this past Rosh Hashanah, I had a conversation with one of my teenagers, who told me that he feels like a phony when davening. He said that even though in his head he knows he’s talking to Hashem, he doesn’t always feel it in his heart. Fortified with my own introspection, we discussed how important it is to act the part of having kavanah, because it’s forcing ourselves to do this consistently that allows us to access real connection.

We both agreed that in the three-plus hours spent saying Shemoneh Esreh during the Yamim Noraim, there would be at least five minutes where the connection was real. However, we can only tap into the connection those five minutes offer because of the work we put in the rest of the time.

Then, on Succos, I read a couple of things that further inspired me. One thing, attributed to Rav Chaim Kanievsky, was that looking in the siddur is 50 percent of kavanah. If that was the case, then I was halfway there. Another article mentioned a woman with a professional career (I don’t remember if she was a doctor or lawyer) who made it her business to daven three times a day. I was jealous of her and decided that I wanted to do that, too.

I value consistency, so once I started this program, I wanted to continue it and challenge myself to see how long I could keep it up. There have been misses. Some mornings, I cannot get out of bed early enough, even though I know from experience that getting up early to daven will not make me more tired during the day. Some afternoons, I’m too busy at work to take off a few minutes, and if my husband has to rush out to Minchah when I get home, his tefillos take precedence over mine. But part of my growth is the recognition that picking myself up and continuing to daven, even though I will not set any records with my consistency, is still meaningful.

Honestly, my kavanah is still very poor. My connection to Hashem through tefillah is still weak. It’s called avodah shebalev because it’s work. It’s something we have to focus on and work on constantly. One good tefillah doesn’t necessarily make it easier to have kavanah the next time — we still have to put in effort. And many times my brain is pulled in so many directions; between running the house, taking care of the kids, and working, it feels impossible to stay focused.

I try not to get down about it and choose to focus on my successes. I am making time for tefillah. I am showing Hashem and myself that this is what I value, and I am willing to sacrifice for it (waking up earlier in the morning, only winding down at night after I have finished). I hope that in the future I will recognize that it’s not a sacrifice at all, that it’s a gift Hashem has given me, but for now, I’m proud, and I applaud myself for prioritizing this.

And here’s a side benefit that I love: I love that my toddlers know to come downstairs and look for me in the study because I’m davening. I love that my two-year-old brings me a siddur after I bentsh licht and starts singing Lecha Dodi. I love that my teenage daughter sees me saying Shemoneh Esreh as she rushes out the door in the morning.

I love this because intellectually I know that this is important. And even though I don’t often feel the connection to Hashem through tefillah, I do believe that if I continue to daven consistently, there will be moments that I do feel it, and that as I focus on this, I will be able to access those feelings more often.

100 Moments

Even when I can’t find the time for a full davening, there are a hundred moments a day to connect. Saying a brachah with kavanah, answering my kids’ million-and-one existential questions, being present and aware of the good in my day and attributing it to Hashem and thanking Him for it… You can be a connected, solid, frum person in your own way, even if it’s not the ideal or perfect way.

Just Talk

Davening is like exercise — you may not be in the mood to do it, but you’ll feel great after you did it. Just. Talk.

Dry Spell

Many times, after a period of intense tefillah, I experience a dry spell where I feel like my tefillos are uninspired. The first time I felt this was after my wedding, but it’s happened a lot since, and I always feel guilty. I’ve since learned to accept the cycle — I need to disconnect to reconnect.

Growing with Life

A lot of us leave high school with the impression that we’ve mastered something — it could be tefillah, it could be tzniyus, it could be a certain middah.

Then you get married and have children, and life happens, and you realize that your “mastery” was actually very shallow and immature. After two years of never once sleeping through the night, you realize that no, you have not mastered the middah of menuchas hanefesh, and are in fact a very cranky and irritable person. Or that the connection that you felt as a teen when you whispered every word of davening wasn’t such a strong connection after all, because when you have no time to daven, you barely think about Hashem.

I wonder what would happen if we taught our teens that our connection with Hashem will hopefully deepen and grow with us through life’s phases. Our teenage understanding of tzniyus is meant to be limited and shallow, and it’s something that can and should hopefully grow as we become adults, with more awareness and maturity. In a similar vein, our need to daven and our need for connection with Hashem isn’t meant to reach its peak on the last day of seminary. It’s something that will take on different shapes, forms, and urgency as our roles change.

We need to accept life’s stages to experience growth. I’m not trying to be a sem girl anymore. Heaven help those who are. And while I may have davened more nicely in sem, I would be shocked if I was more connected then than I am now. Yiddishkeit gives us a framework in which to grow. I see my role now as mastering my middos of patience, giving, vatranus. Not sitting and saying Tehillim for hours.

Celebrate the Little Wins

Erin Stiebel

E

very time I started to type a response to your question, I deleted my words. Praising your bravery in writing this letter or validating your struggle seems demeaning, and seriously, who am I to do that?

I had a chavrusa and a class after that, which gave me more time to think about your important question. As we unpacked the nuanced halachos of borer, my chavrusa, a giyores, gently sighed and said, “I love that there are so many ways to connect to Hashem.” How true!

I finished learning with her and moved on to a small vaad on emunah for high school girls. After discussing how happy we could all be if we trusted in Hashem, one girl asked if she could speak to me privately. She expressed how hard it was for her to daven, crying, “I want to want a connection to Hashem.”

Then I got a text from a former camper I hadn’t spoken to in some time. “Random question, but where in davening can I personalize the tefillos and just talk to Hashem?”

Okay, Hashem, point taken.

My dear friend, a lot of us find davening hard, myself included. Whether you’re in high school or seminary, are single, married, or a mother, every stage brings its own slew of distractions that make us struggle to find time to daven, let alone have an inspired davening.

But as I once heard many years ago, just like in any valued relationship you would never give someone the silent treatment, so too in our relationship with Hashem, we should never give Hashem the silent treatment. We’re on a lifelong journey to connect with our Creator, and we need to invest in that relationship.

We must keep trying, and we must celebrate the little wins.

Some days my siddur gets more use than others. Some days it feels like a prop I carry around with me from room to room, chasing after my children, as I attempt to say a few words before someone needs a tissue or a Band-Aid.

Some days I’m gifted the clarity of mind to use my precious moments of calm to daven like in the good ol’ days. But most days, my davening is an endless disjointed string of bakashos and hoda’ah, alternating back and forth depending on the moment.

“Hashem, please don’t let my child dump that container of cereal… Hashem, please don’t let me lose my sanity picking up 8,000 Cheerios off my floor… Hashem, I’ll be a much more pleasant mom if my kids help me clean up… Hashem, thank You for the best kids in the universe, and for the gift of patience.”

I have endless conversations with Hashem all day long, from the most mundane of topics to the holiest. These conversations strengthen my emunah and make Him more real to me.

And when I overhear my son whispering, “Hashem, please help me beat my brother at knock hockey,” or hear another say, “Thank You, Hashem, for helping me find my favorite socks,” I feel hopeful that in their own way, Hashem is real for them, too.

Mrs. Erin Stiebel is a senior educator for Partners Detroit and the director of NCSY GIVE, a chesed-focused Israel summer program for high school girls.

From the Black Valley

Sara Ross

B

ack in school, the big auditorium was to the perfect place for davening. Around me girls were shuckeling, closing their eyes, and I would just lean into the atmosphere. I had a Shema Koleinu routine: I’d go through all my bakashos, and daven for those close to me, and there was a certain sense of going though a list, of covering it all, and giving it to Him.

I can’t say that my Yamim Noraim were anything amazing. I went to shul, tried to connect, maybe eked out a tear. But what did I know? Sure, there were the ups and down of teen life, but real life hadn’t hit at all. Even on my wedding day, I fasted, I prayed, I said all of Tehillim, and then I stood under the chuppah and begged Him for life and love and children. But was I really connected?

Life hit. I learned that I could be happier than I ever thought possible, and also deeply disappointed, even disillusioned by life. Through it all, I davened every day. I spoke to Him; sometimes more, sometimes less. But we were definitely in conversation, something had shifted since school. I’d grown up. I couldn’t do this on my own, I needed Him.

I had a couple of kids. Recovery from birth was hard, I was a hormonal wreck, but that was in the realm of normal, and I settled into motherhood. I didn’t daven much during those early years, but we stayed in that conversation: I talked to Him, krechtzed to Him, tried to remember to thank Him.

And then I had my third.

I developed severe postpartum mental health problems and landed in the psych ward. Almost overnight I went from life being fine and okay — much more than okay — to hell on earth. My mind became a black valley. Just breathing, just being was torture. I wanted out, I wanted it all to end.

I hung around aimlessly on the ward, walking zombie-like to my room and back, eating breakfast with a circle of suffering non-Jews, all of them eating off treif dishes — sometimes me, too, when I’d forget to bring the plastic bowls from my room or I had none left. My rav said it was okay if the food was cold, but that wasn’t the point.

I was experiencing a breakdown in everything. I’d stay in pajamas all day, basically walking around in pants. I had a siddur with me, but most of the time I didn’t know where it was. Half the time I didn’t say a brachah before I ate. It wasn’t a conscious lapse — it was illness, fog, forgetfulness. But even when I remembered, I barely wanted to say a brachah. When I had the energy, I railed at G-d. What was the point of breaking me in my prime, a mother of three little kids, a beautiful wife? Why?

I had no strength to fight, didn’t for a second see this as a nisayon that could make me stronger. I was an inferno of anger against Him. How could He make this happen to me? Who rips out a vibrant pink flower? I didn’t know that I could recover, that I would recover. I knew days and weeks of horror and worse horror; I thought that I’d snapped and would never be whole again.

But He took His flower out, after too many months. And I blinked back into life with two young kids and a baby. No one, besides those who’d watched it happen, knew a thing. I was a flower restored — at least seemingly. But in the most core ways, I felt I’d been vandalized.

We were over, I thought, Hashem and I. There was nothing dramatic: I was too tired, too encumbered to go “off.” But in those long, horrible months, something had switched off inside. I didn’t speak to Him at all anymore. And though my mind was back, and brachos would jump to my lips automatically, I felt it almost a chore to say them. The Yamim Noraim came, and I said little. What was there to say? He’d taken it all away.

It took me a while to realize that He’d given it all back, too. Every bit of it.

But I couldn’t be grateful, not at first.

My baby reached milestones, but I wasn’t there with him, clapping and snapping pictures like I was with my first two. I wasn’t completely there. I was still healing.

Life continued to happen. Time worked its magic. A few months later, at my mom’s house, everyone was davening Lecha Dodi, and I realized that I could open a siddur and just say the words. Why not?

When I finally said Shemoneh Esreh again, I realized that it had been months upon months since my last Shemoneh Esreh.

I had so many reasons not to feel guilty about not davening. Or at least I told myself I did. But after about a year and a half — of healthy delicious kids, of good times, of satisfying, successful work, of life — I turned around one day and realized: I wanted to be back. With Him. I wanted to reach out, I wanted to believe again.

I started to claw my way toward Him. I had one good tefillah here, another good one there where I didn’t just say the words, I felt them.

Still. I’m a busy mom, I run a busy therapy practice, life is always crazy. Tefillah is not always my focus — but ultimately, I’m back with the program. I talk to Him. I tell Him how rough it is, I thank Him, I reach out and ask for His help, His miracles.

I’m far from a shining example: I see women who daven Minchah against the wall at the supermarket. They have seven kids but make Minchah a priority. I’m not like that. I don’t say a designated amount of kapitlach a day, my Tehillim is dusty. I barely go to shul. But I’m open to Him — to seeing Him in my life, to reaching out, and yes, to shouting as well, even if a siddur doesn’t feature much in all that.

I know what it’s like to be completely off the program — and to have all the justifications for being that way. But in the end, I’m back on, and there’s nowhere else I could be. Nowhere else I’d rather be.

Invite Him In

Mrs. Elana Moskowitz

F

irst, I want to commend the letter writer for reaching out. Sometimes when we take a stark, unembellished look at ourselves and are unsatisfied with our reflection, we choose to take the path of least resistance and ignore what needs to be addressed. Recognizing that something has to change is the more honest, albeit painful, route.

I agree with the writer when she says, “I can’t imagine that I’m really the only one with this problem.” In fact, I believe there are many other “normal, happy” young women who, underground, are struggling with tefillah. Part of this is the nature of formal tefillah. Tefillah is an art, and like all art forms, it improves with investment and repetition and atrophies when we ignore it. This may explain why the writer finds it so challenging to successfully restart davening.

When we haven’t exercised a muscle for a while, it becomes stiff and resistant, and the difficulty restarting an exercise routine is compounded by the muscle’s inertia. Right now tefillah has the status of an inert muscle, and jumpstarting a process of davening may require more stamina than we think. This may be why, “Day one, it works. Day two, maybe. Day three, I don’t even remember that I wanted to do this.”

For sustained davening to happen, we have to make it a habit. That means sometimes we have to power through and daven what we’ve committed to, even when we don’t “feel it.”

Many years ago, someone approached Rav Shlomo Brevda ztz”l about davening a specific tefillah for which she rarely had kavanah and often found herself simply mouthing the words. He encouraged her to continue with it despite her subpar performance so that she “wouldn’t become lazy.” Habit is a potent tool in avodas Hashem, and many people have developed significantly by adhering to specific behaviors that became intuitive, nonnegotiable practices with time.

At the same time, part of the writer’s problem is her feeling of disconnect, and even if making davening a habit will resolve one part of her dilemma, it still leaves much to be desired in her feelings of connection to Hashem.

An important starting point is recognizing how much Hashem loves us and desires a relationship with us. On the tefillah of Ahavah Rabbah, the Zohar (Shemos 5) teaches, “If Yisrael realized the extent to which Hashem loves them, they would roar like a lion to pursue Hashem and cleave to Him.” Love is reciprocal. When we feel love from another person, we’re practically compelled to reciprocate. That’s why habitually contemplating how much Hashem loves us and desires a connection with us is a powerful motivating force to pursue a relationship with Him.

Part of cultivating a relationship with Hashem is inviting Him into the mundane, “trivial” spaces in life. Hashem isn’t only a part of my life when I make brachos and daven. We can conduct an ongoing, daily dialogue with Him that serves as the background music to our day. Whether I’m washing dishes, waiting at an annoying traffic light, or untangling a thorny problem at work, I can invite Hashem into the highs and lows of my day. Periodically asking Him for siyata d’Shmaya and success, or alternatively, unburdening myself to Him with a challenge, and then thanking Him when things are resolved, is a formidable means to ensure a sustained connection with Him.

This also reminds us that Hashem is not a remote, distant entity, but rather a dynamic and eminently present part of our life.

Formal tefillah differs from this form of daily discourse, which can transpire at any time of day. Tefillah has set times and parameters, and that is why the habit factor is such an integral piece in making tefillah work. However frequently, a well-placed motivational thought can remind us why we want to daven in the morning.

The writer mentions that she is a mother. There is no greater gift that a mother can give her child than sincere tefillah on his or her behalf. A child whose mother davens for him every morning embarks on his day with an extra measure of siyata d’Shmaya, a spiritual advantage that a child who wasn’t davened for lacks. Imagine the difference between a child sitting in a class of 25 children, with a protective ring of tefillos buffering him. That could be our child.

It’s our prerogative to gift him with that protection by virtue of daily tefillah on his behalf. Making tefillah a relevant, even urgent, endeavor that addresses our current needs can motivate us to daven when we’re feeling overwhelmed at the prospect of picking up a siddur.

Another important and perhaps counterintuitive idea is to daven to Hashem for help in connecting to and achieving consistency with davening. We forget that we may appeal to Hashem for anything, even for the things we imagine are our own responsibility. Nothing falls beyond the realm of Hashem’s purview.

Finally, I strongly suggest the writer engage in some form of tefillah education; a shiur, book or sefer, or mentor. Even if she believes she learned everything there is to know about davening in her younger years, life changes, and the messages of our youth resonate differently when we’re at a different life stage. I truly believe that if the writer revisits the subtext, the nuances and implications of every brachah in Shemoneh Esreh, she will be pleasantly surprised to find countless opportunities for connection with Hashem.

With deep respect for her willingness to initiate the process, I wish her true hatzlachah in her quest.

Mrs. Elana Moskowitz has been teaching in seminaries for over 20 years.

This Time, In Joy

Yaffa Epstein

AT

my seminary graduation, one of our rebbeim spoke about Hazorim b’dimah, b’rinah yiktzoru. Those who sow in tears, will reap in joy.

And post-seminary, I learned all about sowing with tears. The years in shidduchim weren’t long (relatively speaking, at least), but they weren’t easy, either. I davened. A lot. My siddur grew yellowed — pages brittle, streaked with mascara.

This wasn’t the first time I’d davened like this. Teenage angst, seminary stirrings, and countless crises over the years had me turning to my siddur. I’d always been a davener, the words cradling me in challenging times, lifting me during the higher moments. I talked to Hashem, cried to Him.

And my tefillos were answered. Engagement. Marriage. Pregnancy. Birth.

Each stage came with intense emotions — joy and gratitude, but also anxiety, confusion, and struggle. There was so much to be grateful for, and so, so much to pray for. I continued to sow with tears.

Life moves on. My family grows. Juggling work, home, one baby, then two, leaves me little time for formal tefillah. And I grapple with the questions: What is left of my relationship with Hashem when there is no Shacharis, no Minchah, no sefer Tehillim? What happens on days when I say Krias Shema before falling into bed and realize it’s the first tefillah I’ve said all day?

I start to worry what I’m teaching my children. How they will learn to value tefillah — and their relationship with Hashem — if I barely say the words?

Slowly, I begin to realize that formal tefillah is not the endpoint of our relationship with Hashem. It’s the beginning. And while at other stages of life, tefillah with a siddur or with tears formed the cornerstone of my relationship with Him, now there are whole new levels to achieve.

I’ve sowed with tears. And I’ve reaped with joy. But our connection has not stalled. And just as I once connected in the lack and the longing, I can learn connect to Hashem in the joy, in the abundance, in the gratitude —

If only I open my eyes.

I begin journaling each morning, noting down where I see Hashem’s support in my daily life. The big things: the apartment rental that Hashem sent our way when we desperately needed it, the people who came into our lives at the perfect time to help us. The little things: the outfit for my baby that I found on sale, the friend I met at a doctor’s appointment who kept me company through a two-hour wait. I daven when I can, and on the days that I can’t, I speak to Him, anyway, sometimes asking, mostly thanking. It feels funny at first, but as time goes on, it becomes more natural, and I get comfortable expressing my gratitude out loud.

“Thank You, Hashem!” I say as I sit on the grass one afternoon, playing with toddler and baby. My two-year-old scrunches his brow, and I explain, “I’m thanking Hashem, because I’m so happy. Because I have you!”

A few days later, my son stops in the middle of kitchen, spreads his arms, and smiles up at me.

“Thank You, Hashem! I so happy!” he says.

My heart fills. My eyes fill too. This time, in joy.

Thank You.

A Woman’s Obligation

Rabbi Doniel Neustadt

In general, what is a woman’s basic obligation of tefillah? How can she fulfill it?

According to the Mishnah Berurah, the basic halachah follows the view of the Ramban that women should, at the very least, daven Shemoneh Esreh twice a day, at Shacharis and at Minchah. All women should make every effort to do so.

How does this obligation change when a woman is a metupeles b’yeladim?

If a woman absolutely can’t find the time (or a peaceful five minutes) to daven the minimum because she is overwhelmed with raising her children, then she is exempt from Shemoneh Esreh, and she should just recite as many of the birchos hashachar as possible.

What defines a metupeles b’yeladim? What if the woman is not actively caring for her children, but is busy with the other tasks involved in running a household — shopping, laundry, housework, or going out to work?

All of that is included in raising her children, and if she can’t daven the minimum, then she is exempt. But with proper organizational skills and some planning, most women are able to find the time to fulfill their basic obligation.

Should a woman begin davening Pesukei D’zimra if there is a strong likelihood that her young children will need her? What about Shema? Shemoneh Esreh?

She may start Pesukei D’zimra and Shema, and if she must stop to care for her children, she may do so. She should not start Shemoneh Esreh if there is a strong likelihood that she will not be able to finish. At this point, she is exempt from davening Shemoneh Esreh altogether.

Should a woman attempt to daven Shemoneh Esreh if there is a strong likelihood her children will need her, but she can ignore them (i.e., have a child tugging at her skirts or leave a baby crying) in the intervening time? Or is it better for her not to try if this is the case?

If she can maintain minimum concentration, then she should daven Shemoneh Esreh, as long as she is confident that the children are okay.

If a woman is davening Pesukei D’zimra and her young children need her, can she speak to them? What about Shema? Shemoneh Esreh?

If a woman must talk during Pesukei D’zimra or Shema because of the needs of the child, she may do so. She may not talk during Shemoneh Esreh, unless, of course, there is some type of emergency.

If a woman recites the words of tefillah but feels as if she recited them by rote, without a sense of kavanah or connection, has she fulfilled her obligation of tefillah?

If a woman has a hard time concentrating on the words of tefillah, at the very least, she should concentrate on the meaning of the first brachah of Shemoneh Esreh.

While women should make every effort to daven, the demands on their time may conflict with their ability to daven.

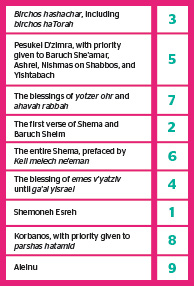

Below is a list outlining the parts of Shacharis that should take priority for a woman whose time is limited. Depending on how much time she has, she should say as many tefillos as she can, reciting them in the order in which they appear in the siddur.

Get to the Core

It seems to me that your issue is not that you aren’t davening, but that you have no connection to Hashem. Why?

I don’t know you and can’t tell you what that is… but I can tell you what I’ve seen in my life. A woman who is emotionally dead inside — if she’s lost touch with herself, her inner aspirations, the “ani” of who she is — won’t be able to connect. Explore what’s going on inside you. Has stress or exhaustion or lack of time with your mounds of other responsibilities caused you to neglect nurturing your own inner identity? Your neshamah?

Has the world’s focus on materialism taken you over, as it has most of us, so that your inner core is deadened, despite your cognitive awareness of where you want to go in life?

In the Ramchal’s introduction to Mesilas Yesharim, he outlines a surprisingly contemporary list of causes that may distract us from focusing on our ruchniyus. He lists the stresses and routine of life, etc., as well as other (more insidious) potential causes. While I don’t know what your core struggle is, if you want to delve deeper, this might be a good place to start.

Riding the Wave

I could relate to nearly every word of your letter. I don’t have any grand advice, but with lots of little ones around, baruch Hashem, and a busy household, I find my davening time to be so limited. I think aiming for consistency doesn’t work well for me — if I make a kabbalah and then miss a day, I feel like, Oh, well, I’ve fallen off the bandwagon, that’s it, I give up.

What does work for me is the overall relationship outside of set, formal, consistent times. So, even if I didn’t manage to say brachos today, but I spoke to Hashem and begged Him for help with this or that while driving back from carpool, that’s connection, that’s bringing Hashem into my life, and it feels good.

One day when my life is calmer, I’ll have more time for set consistent tefillos, but I don’t want to lose my relationship while waiting for that time, so I try to have a lot of conversations with Hashem outside the siddur.

I’ve also found that when I need something big, and it’s major, I manage to find more time for formal tefillah (and it works). Right now you’re trying to get through the days as a young mother, so enjoy, breathe, talk to Hashem in your own words. One day you’ll have to get your daughter into high school or you’ll have a son in shidduchim and the siddur will be waiting.

I want to say that I also spent my year in seminary davening my heart out for specific things, and it’s 20 years later, and I literally feel like I’m still riding on all those tefillos, and they’re still working. You have no idea how far that one tefillah can take you, what brachah it can bring into your life, what siyata d’Shmaya.

Also, daven to want to want to daven. It works.

Rain, Wind, and Tears

Batya Cohen

F

or the longest time I didn’t daven.

A child in hospital with multiple health issues, life running away from me until I couldn’t remember who I was or what day of the week was shining at my weary eyelids. Who had time to daven?

Had I wanted to, though, I couldn’t daven. Something had frozen inside of me. Me, the emotional girl whose heart and soul were bound in her siddur… couldn’t. I’d opened the siddur, mumble my way through brachos, and find a reason to do something else.

I was disgusted with myself. How can you not have davened since… last week? Month?

Sitting on the couch Shabbos morning, davening with my five-year-old. Hypocrite, hypocrite. What’s wrong with me?

And so the years slipped through my fingertips. The layers hardened and shellacked over my heart. I said nothing but a quick brachos as I was making sandwiches in the morning, whispered the tefillos after I lit the Shabbos candles — but even these were distracted by the little people around me, needing attention.

I ripped articles out of magazines, was inspired by speeches, made and broke more resolutions than I can count.

Just Shema and Shemoneh Esreh.

Five minutes on the clock.

A quality brachos inside the siddur.

I would hold out a week, or maybe, if it was Elul, soldier through till Hoshana Rabbah.

I used countless excuses. Hashem knows I’m busy. Hashem sent me all these challenges, if He wanted my tefillos He would give me time to daven.

But time wasn’t really the issue. I wasn’t fooling myself.

I went to the Kosel. I sat on the bus, fingering my siddur. I would stand there and open my heart, beseech Him to show me how to reconnect. I would cry again, and the floodgates would open.

I reached the Kosel Plaza, repentant.

And there was a massive group of tourists, busloads of them, and I couldn’t concentrate on a word I was saying.

I went into the little room for indoor tefillos, but every other frum woman had had the same idea. I couldn’t breathe. I said Shacharis, hemmed in on all sides by crying, whispering women, and begged for one tiny tear.

Nothing.

I went home convinced that Hashem didn’t want me to talk to Him any more.

I gave up.

This was just the woman I was going to be. An actress. A frum mother with kids who davened beautifully enough to bring a lump to her throat, but a fake.

I had been rubbed raw by a year of a very challenging family crisis and I needed to recharge. I went alone on a desperately needed vacation.

And on my schedule was daven Shacharis at the beach. Because I still couldn’t reconcile my outer persona with the dead part of me, the one that didn’t daven.

The phone rang… and I picked up, planning to just say hi.

Another family crisis, even worse than the previous one that had drained me to empty. I spent hours on the phone that I rued answering, and then switched it off to try and sleep.

The next morning I told myself to take the siddur to the beach, because who knows? Maybe I could squeeze out some birchos hashachar despite everything.

I walked and walked and wanted to cry. I looked at the striated crags above me, at the gentle waves below. All the power and beauty that always moved me so much, and I was mute.

I sat on a rock and looked at it — a rock created by years and years of wind, rain, sand, and sea. Salt and storms and broiling sun, and here was a rock that could one day form a mountain.

Little me, sitting on a rock. Surrounded by the immense force of Hashem’s creations, puny me. I thought about Rabi Akiva and the hole formed by water. Couldn’t that be my heart?

And then I was standing and yelling. Why me? Why Hashem, why why why.

And I opened the siddur and davened, forcing my concentration back to the page again and again why why why.

You don’t want me. Why. You keep hitting me. Why.

Shema koleinu. Why.

And then it came, one tiny drop of salt and wind and rain and hurt and anger, trickling down my cheek hesitantly.

I let it drip down, hoping it would land on my heart and make a hole.

And it did.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 828)

Oops! We could not locate your form.