Can We Keep the Stars in the Classroom?

| September 9, 2025We’re losing quality teachers because the numbers just don’t add up

I

‘ve always had butterflies on the first day of school. First, as a student. Then, as a teacher. As a mother, the butterflies are most intense.

I was chatting with a friend on the first day of school. “I can’t stop thinking about my girls,” I said.“I hope they have good teachers. I hope they’re happy.”

“You must be even more nervous because your daughter is the teacher!” I added. Her daughter Mindy was a sixth-grade teacher.

“Nothing to be nervous about this year,” she replied, “Mindy isn’t teaching anymore.”

I was shocked. “Mindy left her teaching job? It’s so sad that we lost another quality teacher.”

My friend explained the backstory. Her daughter Mindy was the kind of teacher that every parent wished their child could have. Parents requested her all the time. She was creative, positive, innovative, and smart. But more importantly, she had a maturity and depth of character. She was the one who looked out for the struggling children and connected with them. She really cared.

Mindy did a fabulous job for four years, but the salary always bothered her. Her teaching job was her life. It took everything out of her. The hours in the classroom — not to mention the preparation and phone calls with parents — chopped up her day, leaving her with insufficient time to find a lucrative side job.

The school valued her work and gave her small raises over the years. Still, her salary was pitiful compared to the salary of a fresh graduate working in a medical billing office.

At first, Mindy was okay with the compensation, and the satisfaction compensated for the low wages. She was young, idealistic, and didn’t have many expenses. But as she began to think about her future, the numbers didn’t add up.

She decided to do some research among veteran teachers. “Does it make sense for me to stay in teaching for the long run?” she asked them.

They all told her the same thing: No. The salary is not livable.

“You’re better off leaving the field while you’re ahead,” one teacher advised her. “I’ve been teaching for fifteen years, and now I’m stuck. My computer skills are rusty; I can’t work long hours. I’m a successful second-grade teacher, but I don’t have many transferable skills that are valued by employers. In some offices, a nineteen-year-old seminary graduate, who can work nine to five, is more desirable than me. If you stay in the field for fifteen years and then decide to leave, it will be a lot more difficult for you.”

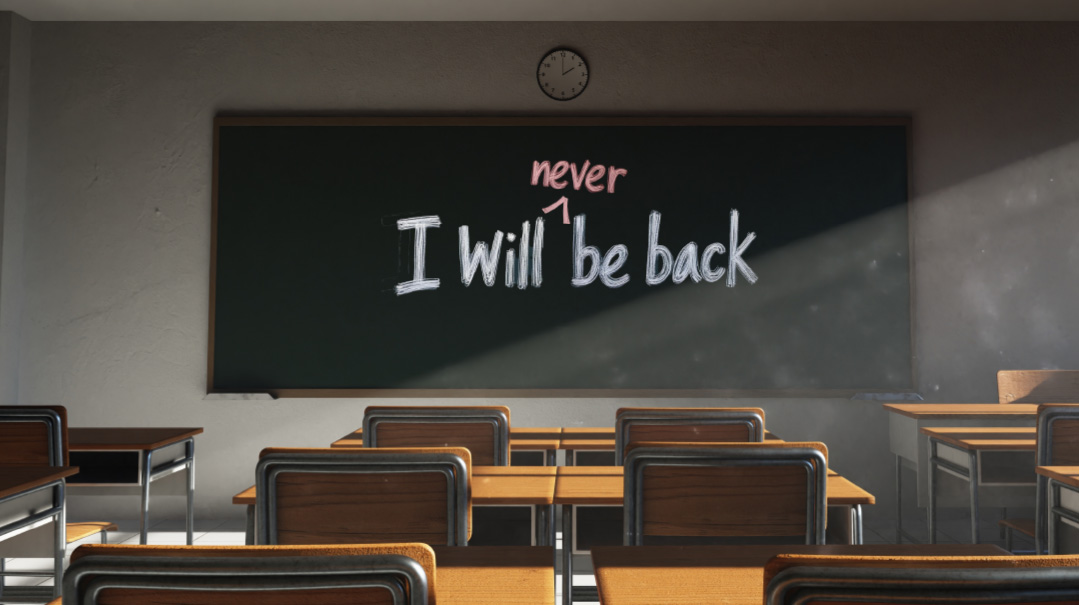

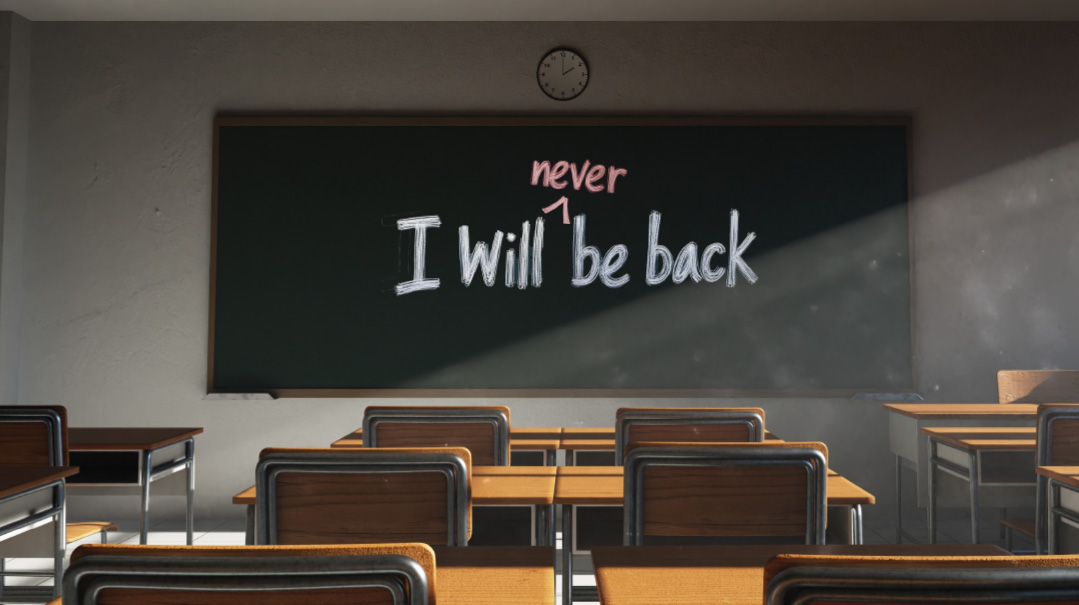

With a heavy heart, Mindy called her principal and told her that she was not coming back. The principal was devastated and tried to get her a relatively large raise, but even that wasn’t doable. Mindy left the classroom forever.

Unfortunately, I’ve heard versions of this story too many times. Of my classmates who became teachers after graduating from seminary, many left the field to pursue lucrative professions and get “real jobs.” (I left teaching after only two years.)

One of my friends, who had been an incredibly successful eighth-grade teacher, left after four years to attend nursing school. “There was no way my husband could have stayed in kollel if I stayed in the classroom,” she told me. “I don’t know how the seminaries push teaching and kollel. To me, it doesn’t seem possible. Maybe it’s a privilege for the rich? Even when my husband got a job, life was so expensive that my family needed a second real income.”

Each time I hear about an excellent teacher leaving the field, I am sad. Because I know just how valuable a good teacher is.

There are certain children — the easy-breezy ones — who will do well in virtually any classroom. I have one child like that. Of course, we appreciate when she gets a star teacher — it’s always nice — but it won’t make or break her year.

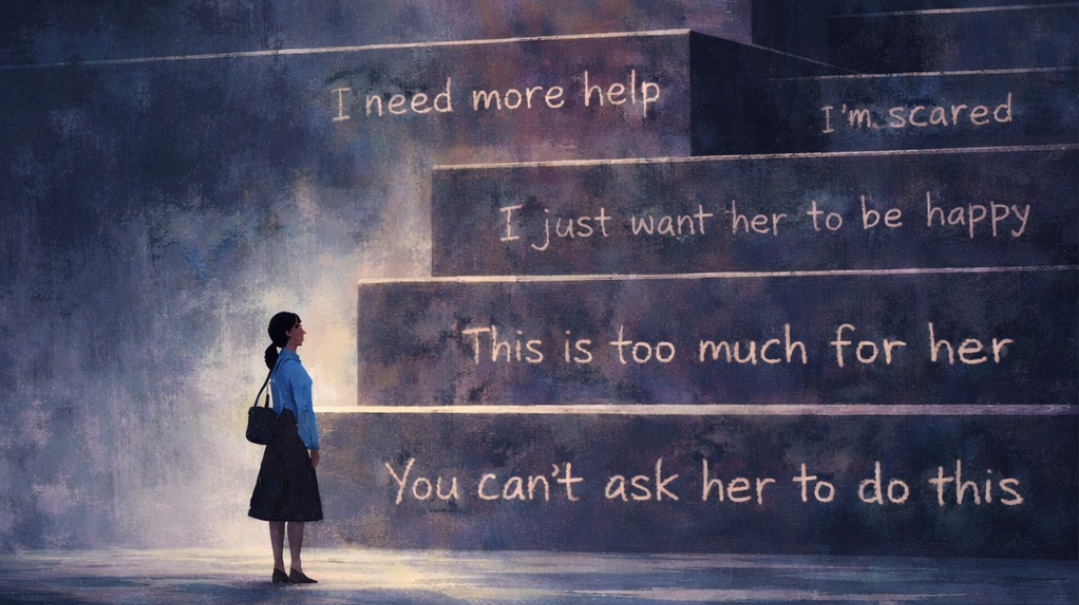

But I have another child who has a harder time in the classroom, and a good teacher is a lifeline for her. We need the teacher to understand her, reach her, and bring out the best in her.

There were the years when she had inexperienced, lackluster teachers. Teachers who didn’t connect and definitely didn’t bring out the best in her. She suffered those years. I suffered those years.

With the right teacher, many behavior problems, power struggles, and “chutzpah issues” magically disappear. A smart, connected teacher will know just how much to push a child and when and how to let go. All parties involved can breathe more easily. A quality teacher understands that success looks different for each child in the classroom.

And it’s not only my child who desperately needs a good teacher. The following example is not scientific; it’s anecdotal, based on years of conversations with mothers from around town. It also varies between each class. But let’s take an average class in a mainstream Bais Yaakov classroom and assume that 60 percent of the class are the “easy” ones. They are well-adjusted children who can keep up with grade-level work. If everything else is okay in their lives, they will be okay with a lackluster teacher.

But what about the rest of the class? Another ten percent of the class may have (diagnosed or undiagnosed) ADHD or ADD. Another five percent come from challenging home situations. Another 15 percent will have some degree of learning difficulties. And another ten percent will have social or emotional struggles.

In a class of 30 children, that leaves 12 students whose year hinges on a good teacher.

I was recently talking to a renowned principal who gives a popular workshop for new teachers. She was giving a series of classes at the end of August. “Honestly, some of these girls don’t belong in the classroom,” she confided in me.

“So why are they teaching?” I asked. “And how did they get the job?”

“Some of them got the job at the end of the summer,” she responded. “They were not the schools’ first choice. The schools were desperate.”

My heart was beating fast as my brain did the math. I thought about the 12 students in each class who wouldn’t click with sweet, well-meaning, but utterly unqualified and inexperienced teachers. (Even with a lower estimate, there must be at least eight students who need a good teacher to understand them.) That’s a lot of suffering children, suffering parents, and suffering families. Because what family is made up of only “easy-breezy” children?

So what happens to those eight to twelve students?

I’ve heard the gripes, frustrations, and horror stories from the parents. In some of the cases, the children did well with one of their teachers and fell apart with another one. I’ve heard this mantra so many times. My child needs a good teacher.

It’s obvious that we need to get the stars, and more importantly, keep the star teachers, in the classroom. We need the salaries to be sufficient and somewhat comparable to other jobs. And perhaps that would raise the prestige of teaching, because in recent years, a teaching job is not as glamorous as it used to be.

But that would all cost A. Lot. Of. Money. Money that the schools don’t have.

Unfortunately, there are no simple solutions.

Parents are already struggling with their tuition bills. And fundraising is never easy; we’re all stretched thin with our tzedakah commitments, Rayze.It pages, and building campaigns.

But I’m thinking about the 12 students in a sixth-grade classroom in Lakewood that need a good teacher. And they could have had an incredible teacher who would have connected deeply with each girl. She would have brought maturity, sunshine, and empathy into the classroom — along with creative, solid learning. But that star teacher is getting a degree and going into business. And in her place will be a fresh seminary graduate who may or may not do a good job.

If you’re the parent of one of those 12 girls whose year hinges on a good teacher, what would you do to keep the star in her classroom?

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 960)

Oops! We could not locate your form.