Calm Amid the Storm

Rav Gershon Edelstein's legacy of chareidi political caution

1.

IN January, two weeks after Israel’s current government was formed, and a week after new justice minister Yariv Levin announced his judicial reform package at a press conference that sparked a major protest movement, Rav Gershon Edelstein ztz”l asked Degel HaTorah’s MKs to meet with him at his home on Raavad Street in Bnei Brak.

In those heady days after the government’s formation, the Israeli right was still intoxicated at its crushing election victory. The masses had yet to take to the streets, high-tech workers had yet to strike, and right-wing MKs jostled to declare allegiance to the Levin-Rothman clique, in the face of a defeated and disorganized left.

Rav Gershon Edelstein, who was first and foremost a rosh yeshivah and educator for eight decades, would cross-check information with different sources, like every veteran mechanech. And what worked well within the walls of the beis medrash would also work well in the political field, as it had for Rav Shach, who sat on the same hill — the Ponevezh yeshivah in Bnei Brak.

During a conversation with a bochur, Rav Edelstein learned that some Degel HaTorah MKs were giving triumphant interviews in which they declared their allegiance to the Levin-Rothman agenda, while harshly critiquing the High Court.

Rav Gershon recognized that this arrogance and disregard of the limitations of power could lead Israeli society to the abyss. When he learned that Degel HaTorah MKs were involved, he summoned them to his residence to give them an unambiguous order: “Don’t give interviews, and don’t talk.”

When asked later why he gave that instruction, he cited the words of Yaakov Avinu to his sons, “Lamah titra’u (Why should you be seen)?” as an indication that we must never antagonize public opinion, even when borne on the treacherous waves of political success.

2.

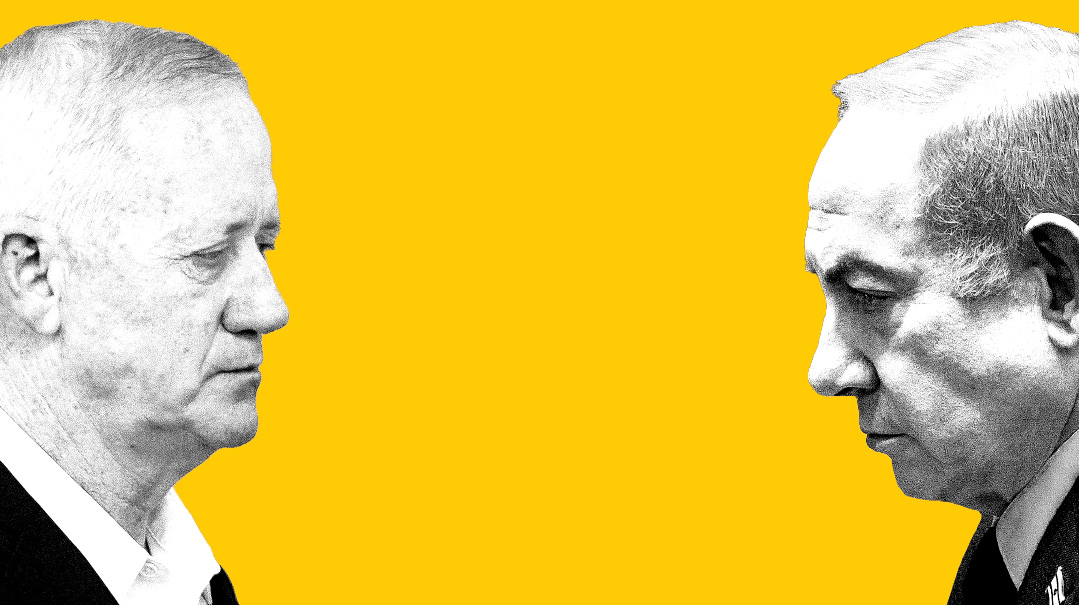

“For Rav Gershon, the judicial reform was a project of Levin and Netanyahu,” Degel HaTorah MK Yitzchok Pindrus explains to Mishpacha. “For him, it wasn’t an end in itself but rather a tactic to overcome the obstacles imposed on us by the High Court.

“Rav Gershon’s message to us was that if the reform was necessary to overcome judicial obstacles, then by all means do it, but don’t pursue it as an end in itself. And so when he saw what it was leading to, his instructions were clear: If it has to wait, wait, and don’t make the means into an end in itself.”

Pindrus pinpoints the crux of Rav Gershon’s leadership philosophy. “Rav Gershon’s instructions to us boiled down to this: As chareidi Jews, we must make sure we have the ability to learn Torah and fulfill the mitzvos in Eretz Yisrael without interference, and to make this possible, we have to do whatever we need to and can do. But this can’t occur in a climate of constant warfare with the secular community. When we come up against High Court rulings, the question of when and how to deal with this is no longer a matter of principle but of tactics.

“So when Rav Gershon asked us not to give interviews, he was essentially telling us to focus on the ikar rather than on the tafel.”

This approach came to the fore during his brief leadership of the Degel HaTorah movement, but above all in his spiritual leadership as head of the Ponevezh yeshivah. When his associates and family members pleaded with him not to leave the heichal of the Ponevezh yeshivah and everything its gilded aron kodesh symbolized, Rav Gershon insisted on abandoning it for the nearby heichal hakedoshim, which was then an old and neglected building.

“I never saw someone who was mevater losing,” he told his students, as he would later tell the MKs who followed his orders.

Tactical retreats with a view to attaining an object peacefully were a way of life for him. And it wasn’t just about middos, but a calculated leadership strategy of putting the means above the end.

3.

Rav Edelstein was well attuned to the potential chillul Hashem impact of any political move among the broader Israeli public. The sole occasion when he differed from Rav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l was at the height of the Covid pandemic, when Yated Ne’eman, Degel’s party newspaper, was about to run an article implying that Torah learning should continue as normal, in defiance of state regulations.

As someone who prioritized Torah study before everything, but was nevertheless attuned to the currents of Israeli public opinion and understood that chareidi society couldn’t completely disengage from the broader culture, Rav Gershon uncharacteristically ordered for the article to be scrapped, lest it cause the slightest incitement against the chareidi public, even indirectly.

Rav Gershon always knew how to put his finger on the crux of every issue, and gave his opinion first and foremost about that. Just as he prioritized an individual talmid’s personal welfare over the public image concerns of any institution that preferred to kick out those who diverged slightly from the beaten path, he also considered the impact any coercive political move would have on kiruv of secular and traditional youth.

Rav Gershon always preferred to get things done while avoiding a head-on clash with the secular street. So when he saw chareidi MKs going on the attack against the defeated center-left on judicial reform, he decided to silence them, simple as that.

This way of thinking was evident in everything he did, up to his last days. During the last two weeks of his life, he instructed Degel HaTorah MKs not to hold a gun to Netanyahu’s head over the retroactive grants for yeshivos and kollelim, despite the clear financial impact such a move would have on avreichim — Degel’s base. The financial implications of the grant, on which Agudas Yisrael MKs wanted to hinge their support for the budget, were clear: Every avreich would have immediately received over NIS 1000. But Rav Gershon understood the PR implications, and ordered the demand not be made in the name of Degel HaTorah.

At a time of mounting incitement against the chareidim, doubling down on the extra funding would have been like pouring fuel on the fire. Rav Gershon, who always knew that the chareidi community can’t live in a bubble, decided to let it go. Once the basic needs of the Torah world were accounted for in the budget, he refused to demand the full sum promised in the coalition deals, for fear of fanning the flames of anti-chareidi hatred.

The rosh yeshivah didn’t content himself with staying out of the matter. Against the view of Agudas Yisrael’s Moetzes, he sent a direct message to Netanyahu that Degel HaTorah would not insist on the budget issue. One Agudas Yisrael minister shared, “Bibi told us, ‘I can’t give you the extra money and go to war with the Finance Ministry and the media while Gafni sends me a message from Rav Edelstein that we shouldn’t double down and go to war.’ ”

4.

“How will it affect the yeshivah bochur? And how will it affect the secular youth?” Rav Gershon asked when organizers of the massive right-wing protest rally in Jerusalem asked to include the chareidi community in a separate compound, in hopes of bringing total participation to one million people.

The Israeli right felt the need to respond somehow to the left’s protests, and hundreds of thousands came to Jerusalem to strengthen the government’s hand. But Rav Gershon pinpointed what for him was the crux of the issue. For him, what mattered more was how it would affect kiruv with the Israeli center-left and how it would affect the yeshivah bochur who went to the protest. And when he got his answer, his decision was clear. On his initiative, the Moetzes Chachmei HaTorah issued a boycott of the event, in a statement that reverberated within the chareidi community and beyond.

Rav Gershon gave similar instructions on another, no less controversial issue, just days before his passing. He was the one who authorized chareidi MKs to let go of the draft law for now and allow Netanyahu to pass the budget before regulating the issue, as was promised in the coalition talks.

Despite concerns that the High Court wouldn’t allow Netanyahu to push the matter off any longer and would issue a ruling compromising the position of Torah learners, Rav Gershon made a tactical decision (once again in opposition to Agudas Yisrael’s Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah) to approve the request for a delay in the matter.

From his vantage point on the hill, which enjoys a view of Tel Aviv as well, Rav Gershon understood that if the chareidim insisted on passing the draft legislation now — in the face of secular demands for “equality of burden” and protests outside yeshivos and even his own home — they might win the battle and pass the bill, but they would lose public opinion, and with it, the war.

Fulfilling the coalition agreements — and even the draft law — were for him only a means, not an end. The goal was always to enable the Torah world to exist without interference and always think ahead about which moves would lead to kiruv in the secular community and which would lead to hatred and estrangement. Rav Gershon realized that any bill that put Torah learners at the eye of the storm would cause more harm than good, and therefore gave the go-ahead for delaying the legislation.

5.

Like Rav Aharon Steinman in his day, Rav Gershon was a leader who understood the limits of power and preferred to avoid head-on confrontations with the secular establishment. But this was only true as long as he felt that no red lines were beings crossed and no vital principles were being conceded— and there’s no better anecdote to illustrate it than this.

A week and a half before the list filing deadline during the last election, Rav Edelstein’s grandson Motti Paley received a phone call. Rav Edelstein’s grandsons were completely unknown to the wider public, because his policy was to keep a low profile and resolve conflict through dialogue behind closed doors.

But in this instance, Rav Edelstein exhibited a complete turnaround from his usual moderate, peace-loving self; he was adamant on not ceding an inch.

On the agenda was the question of whether to allow the Belz chassidus, among others, to join a new program to teach math and English in their school system in exchange for full state funding. The chassidus, which for years had suffered from budgetary discrimination — even more than the chareidi community in general — was leaning heavily toward going for it.

And that was when Rav Edelstein stood his ground and made clear that it wouldn’t happen. If it did, Degel HaTorah would run a separate slate from Agudas Yisrael in the elections, even at the cost of one faction failing to cross the threshold and losing the right-wing bloc hundreds of thousands of votes.

The chareidi political world — along with Netanyahu — was thrown into panic. No one knew where Rav Gershon was going with his adamant refusal to allow the core curriculum into chareidi schools, or whether he would persist even to the point of renewing the chassidish-litvish split and remaining in the political wilderness.

When Bibi was assured that things would work out at the last minute, as they usually do, he refused to be comforted.

“Rav Edelstein reminds me of my father, who was still clear-headed and sharp at the same age of 100,” Netanyahu told me in those stormy days. “I’ve learned one thing. He looks so gentle from the outside, asking questions and trying to understand the other side — until the moment he reaches a decision. And once Rav Edelstein makes the decision to split up UTJ on a matter of principle, no one will be able to budge him one inch. He’ll stand steadfast as a rock.”

Netanyahu asked grandson Motti Paley to come to Likud’s HQ in Metzudat Ze’ev for a private conversation, to understand what his grandfather was aiming for and what could be done.

Rav Gershon instructed his grandson to open the conversation with a clear statement. “My grandfather wants me to tell you not to listen to any message given in his name. He has no intention of supporting anyone but you. And with him, there’s no conflict between his mouth and his heart — what I’m telling you here in his name is what he’ll say everywhere.

“But there’s one thing you need to know. Politics, the coalition, and even the funds are a means and not an end, because the goal is securing the existence of the Torah world and preserving our education framework. And because the core curriculum is a vital principle for us, in light of the danger to the entire chinuch system, there will be no backing down, at any price.”

Bibi then asked whether Degel HaTorah would be willing to forgo the first spot in the shared United Torah Judaism list if Agudas Yisrael made concessions regarding the core curriculum. When he received a positive answer and understood Degel’s priorities, Netanyahu set to work and was ultimately able to orchestrate a rapprochement between the two factions of UTJ.

Rav Gershon, whose word was iron, remembered the promise well, and before the passing of the state budget, shortly before his petirah, he called Degel HaTorah chairman Moshe Gafni to ask whether the promise that was made to the talmudei Torah — and not just those from the litvish sector — would be kept. When Gafni assured him this was the case, he approved Degel’s support for the budget.

The moderate man who could read the mood of the secular community made his priorities very clear: Choose your battles carefully, and only fight over vital principles. Without flour, there’s no Torah; but you don’t go to war with the general public over a tangential issue, even when it means budgetary promises to the Torah world will be violated.

Will this approach remain viable after his sudden passing? In the seething cauldron of Israeli and chareidi politics, we’ll soon see.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 964)

Oops! We could not locate your form.