By His Hand

| November 30, 2021It was a long time ago, 19 years, toward the beginning of our lives together

He knew there wasn’t much hope, and as a right-handed person, he was anxious about being able to write

It’s marked on our wall calendar every year: Sivan 22, also known as the yahrtzeit of Abba’s fingers. Macabre humor, I know. We try using other words like “the anniversary of the accident” or “the day we make a seudas hoda’ah,” but it often comes back to “the finger yahrtzeit.”

It was a long time ago, 19 years, toward the beginning of our lives together. This was before we had kids, and teaching was everything to me: meaning and comfort and the wonder of a class of six-year-olds learning Bereishis for the first time. On the day of the accident, I was giving over perek beis to a roomful of wide eyes when the knock on the classroom door jolted me. I remember being frustrated. What could anyone want? What could be more important than this?

A close friend stood there, a nervous look on her face. Before I knew it, a substitute took my place in class, and I was ushered into her car.

“I don’t have good news,” Briny said — and my mind flew to my mother, who had been sick for a while. “Deborah, Emmanuel had an accident.”

Ah, Emmanuel. My husband of two-and-a-half years was strong, young, and in so many ways, infallible. A car accident. How bad could it be?

The police had informed my in-laws, Briny said, but they hadn’t contacted me — and they had mentioned only that it was outside of Sheffield.

Briny took me home. I washed dishes as she sat on the phone at my tiny kitchen table trying to piece together the story, and more importantly, to locate Emmanuel. There are three hospitals in Sheffield, and she made call after call, begging bored receptionists for information. Finally, we hit gold: Northern General Hospital in North Sheffield.

Emmanuel had embarked on a fundraising trip for his kollel, driving a rented Ford Fiesta from Gateshead to London. The drive is 286 miles, most of it a straight motorway. Sheffield is a town about halfway down to London, just another junction on the M1.

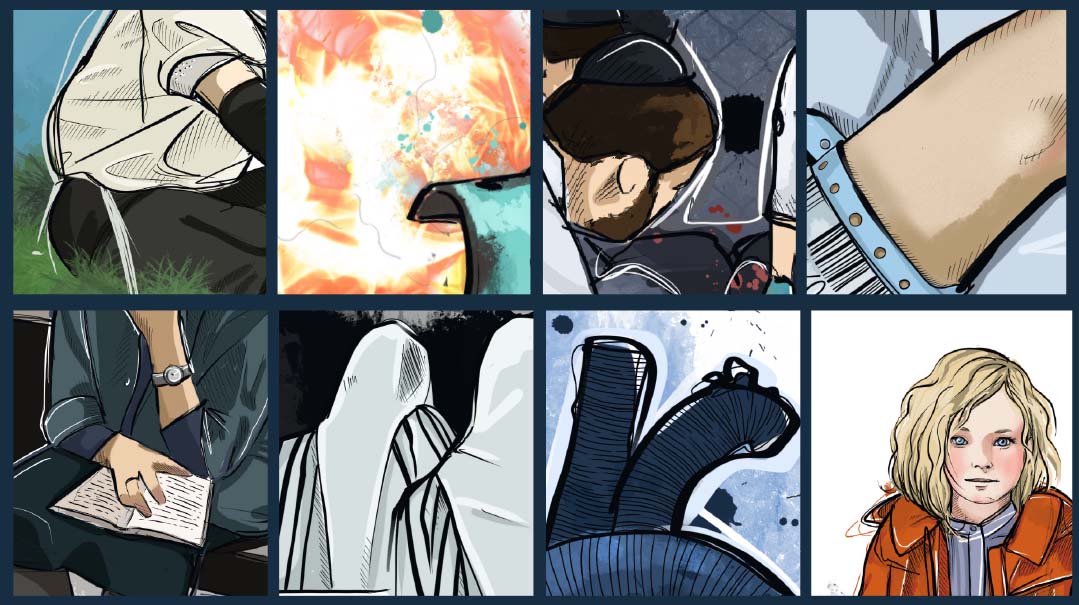

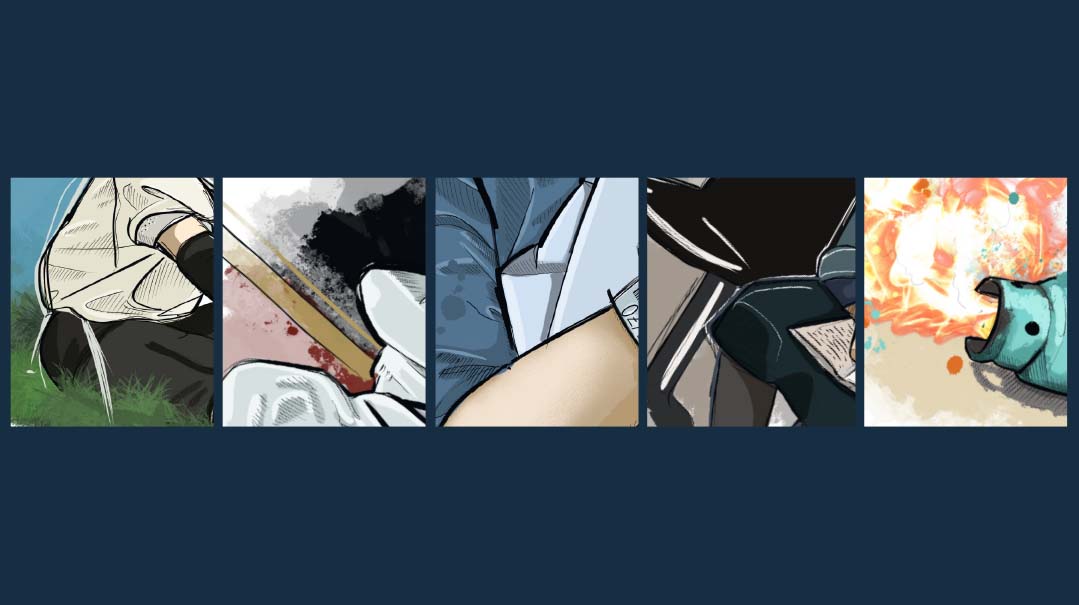

No one is quite sure how the accident happened. Maybe a tire burst, maybe something went wrong with the axle, but whatever it was, it was horrendous. The car flipped twice, and Emmanuel found himself upside down, held in place by his seatbelt. The car had hit the central barrier before somersaulting over several lanes. He doesn’t remember many details, just that someone unstrapped him and got him out. That person wasn’t a medic, and it could have been extremely dangerous, but it saved Emmanuel’s life. Had he been upside down with an open head wound for longer, he almost certainly would have had brain damage.

As it was, the main damage to Emmanuel’s body was nowhere near his head.

Briny soon had me bundled into the car, and with her husband at the wheel, we began the three-hour drive to Northern General. Upon entering the ward, we could see Emmanuel straightaway. His head was bandaged, and he was pale as a sheet. His arm — his right arm — was held up in a sling attached to the ceiling. And Emmanuel was scared, very scared. He had seen the damage: Destroyed elbow. Crushed fingers. He knew there wasn’t much hope, and as a right-handed person, he was anxious about being able to write. (I was still in the dark.)

Surgery was scheduled for the following day. My mother-in-law called a medical askan to ask if we should transfer to a hospital in Gateshead or London.

“It ‘just so happens’ that the best place for injuries like Emmanuel’s is Sheffield,” the askan informed her, explaining that Sheffield is the Steel City, world-renowned for its production of steel, and the local hospitals are experts on factory injuries, similar to this sort of damage.

What a massive relief, I thought. We are in the best place possible.

But to be honest, I couldn’t process it. In fact, I didn’t realize until just before the surgery that they actually meant to amputate his ring finger and pinkie — yes, I was that slow. And it didn’t stop there. When the surgeon told me how bad the situation was, I didn’t really understand or react; it was all just too big, too much.

“All the glass embedded in his arm poses a real problem because of infection risk,” the surgeon said.

Grass? I thought.

I was numb to the reality.

Before the surgery, it finally hit me that they were removing two of my husband’s fingers. Baruch Hashem, once I actually comprehended, I was well equipped to handle it. Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Dunner, the leader of chareidi Jewry in the UK, spoke at my school every year before Yom Kippur — and he had lost the same two fingers, as well as part of a middle finger, while kashering a factory. Nonetheless, Rabbi Dunner achieved so much; this knowledge made our situation a little less scary to me.

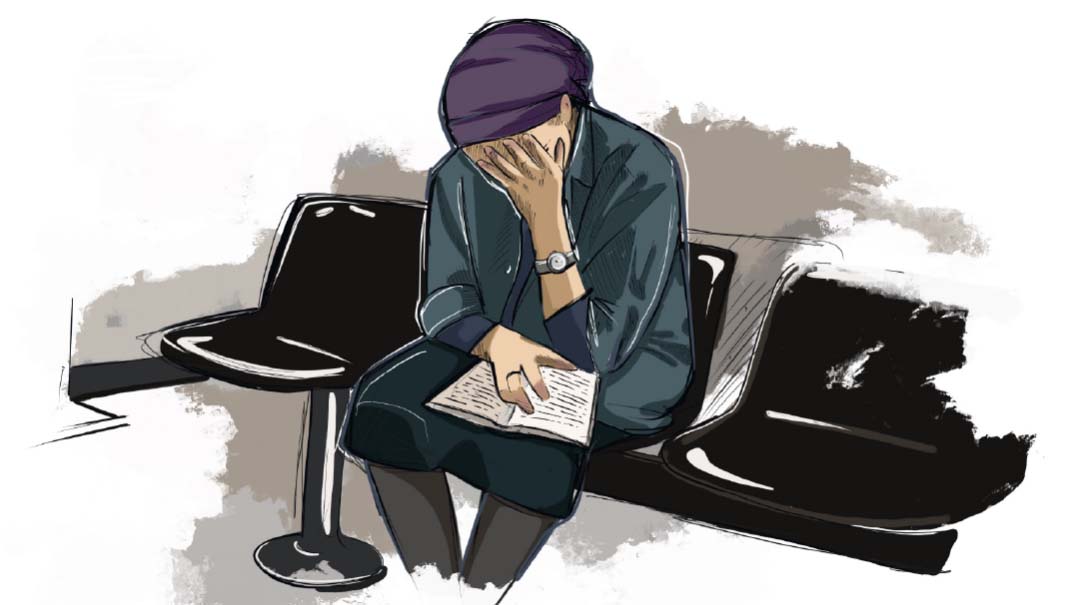

Emmanuel underwent two surgeries within the first week: the first to amputate his crushed fingers, and the second to reconstruct his elbow and lower arm. During the first surgery, which was about three hours, I sat in the waiting room and davened. Afterward, a nurse handed me a small brown paper bag for the Chevra Kaddisha in Gateshead for burial, as per the psak we received.

The second surgery was longer, four or five hours, to do skin grafts and vein grafts and countless delicate procedures. In fact, when I heard how major the second surgery was, the first one became a side point, even though the amputations are the most visible part of the accident.

While Emmanuel was in the operating theater, I went to see the car to recover our things. The car… what can I say? The front driver’s side wheel — on the right in the UK — was bent in half, the windows were broken, the doors were dented.

Emmanuel survived that?!

Seeing the damage brought the trauma home for me — and I found that details crowded out the narrative. Emmanuel’s tefillin bag, the one I had painstakingly chosen for him as a kallah, was torn right through (the tefillin themselves were fine). Among the car’s contents had been the 100 challah rolls I had lovingly baked for my brother-in-law’s upcoming bar mitzvah. How bizarre that losses don’t cancel each other out — the loss of Emmanuel’s fingers didn’t numb me to the loss of those rolls.

Recovery was arduous. Visitors drove for hours to be with us, only to find Emmanuel just too ill to see and be seen. I was particularly embarrassed when his rosh kollel came all the way and Emmanuel spent most of the visit vomiting, a side effect of having so much anaesthetic in such a short amount of time. He wasn’t great company. Previously known as Mr. Energetic, my husband lay in bed for hours, the only sign of life the quiet tapping of his foot to the Shlomo Carlebach tunes that filled the room. I must have heard those songs hundreds of times; we both found them comforting. At least the surgeons were happy. Although they were unsure how much use Emmanuel would have of his reconstructed arm, it was the best they could do — they were satisfied with their work. Emmanuel was two fingers down, and because of the grafts, you could no longer feel his pulse, but they told us it wouldn’t affect his everyday life too much.

Returning to Gateshead 12 days after the accident was simultaneously terrifying and joyous. We were surrounded by the love and care of so many; thankfully, most people were able put their own awkwardness aside, thrilled that we were okay. Emmanuel’s recovery took the better part of nine months, but with excellent physical therapy and infrared therapy for the grafts, his body healed. He was able to extend and move his arm — today, Emmanuel has full use of his hand.

The Gateshead Rav, Rav Bezalel Rakow ztz”l, told us that since Emmanuel’s life had been at risk, we should mark the occasion annually with a l’chayim, and I should bring something to work to share the neis.

And so, we mark the occasion yearly. Late at night — the night before, of course, as if I don’t have the date marked on my calendar! — works best for me to bake and construct seven-layer creations, trifles, and mini chocolate mousses. The children who have since filled our lives with so much brachah are sleeping upstairs, and Emmanuel is on hand to help me pack everything into the fridge and freezer. The accident, dramatic as it was, now seems like a blip. Yes, his arm is scarred and will never look the same, but life goes on.

Sivan 22 is our annual day of contemplation and gratitude. Gratitude for the fragility of life, which makes it so precious. Gratitude that a Yid is never alone in This World. Gratitude that chesed does not need equations, that we don’t have to be deserving, and that we don’t have to give back, only to give on. And mostly, gratitude to the Ribbono shel Olam, Who shook us up — and gave us another chance.

Deborah Danan, formerly of Gateshead, recently moved to London where she is Head of Chol in Tashbar of Edgware and rebbetzin of ESBH (Edgware Sephardi Bet Hamedrash).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Oops! We could not locate your form.