Bulwark of the Balkans

| March 5, 2024Rav Yehuda Alkalai (1798–1878) served as rabbi of Belgrade and was an early proponent of Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel

Title: Bulwark of the Balkans

Location: Belgrade, Serbia

Document: The Sentinel

Time: 1918

The Balkans, home to a relatively small Jewish community dating from Roman times, emerged as a center of the Sephardic diaspora following the expulsion from Spain in 1492. Although these Sephardic communities were eventually wiped out during the Nazi occupation of southern Europe in World War II, during the centuries they thrived they produced a number of prominent rabbanim, among them the Alkalai family of Serbia.

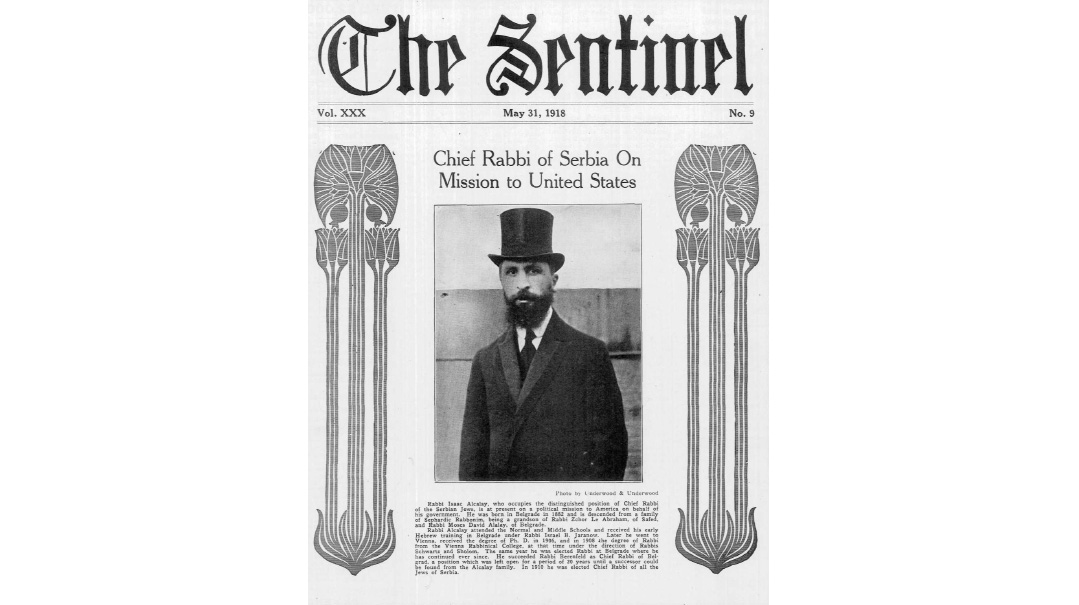

Rav Yehuda Alkalai (1798–1878) served as rabbi of Belgrade and was an early proponent of Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel decades prior to the Zionist movement. His great-nephew Rabbi Dr. Isaac (Yitzchak) Alkalai (1881–1978) enjoyed an illustrious career in the Yugoslavian rabbinate and was a respected leader of the broader Sephardic world.

Having spent his formative years in Sofia, Bulgaria, Rav Yitzchak Alkalai pursued a university degree in Vienna and also earned semichah from the city’s rabbinical seminary. In 1909, he was appointed chief rabbi of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia; shortly afterwards, he was appointed chief rabbi of the whole country.

With the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires in the wake of World War I, several Balkan countries, including Serbia, were united into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Rabbi Alkalai was viewed as a unifying figure by the diverse communities of the new kingdom. In 1923, King Alexander I appointed him chief rabbi of all of Yugoslavia.

This position carried both political and religious importance; the chief rabbi was the sole representative of the Jewish community, irrespective of individual religious affiliation. He performed ceremonial functions in this capacity, and represented the Jewish community’s interests to the government, earning a salary as a public servant. Rabbi Alkalai served in this position until the Nazi invasion of Yugoslavia, after which he managed to escape.

Rabbi Isaac Alkalai’s leadership extended beyond the borders of Yugoslavia to the worldwide Sephardic community. He visited the US as a young rabbi representing Serbian Jewry, and in 1925 was a delegate at the first Sephardic Congress held in Vienna, where he was elected vice president of the World Sephardic Federation. In 1936 he was a founding member of the World Jewish Congress. Within Yugoslavia, he had previously served as a chaplain in the Serbian army during the Balkan Wars, and at one point he served as the president of the Yugoslavian Red Cross. In 1932 he became the only Jewish member of the Yugoslavian parliament, where he advocated for his community’s interests in a climate of rising anti-Semitism.

The early stages of World War II saw Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria join the Axis, and Hitler pressured Yugoslavia’s sympathetic government to join as well. Hitler needed to solidify his position in the Balkans to be able to pressure the British Navy in the Mediterranean. The Serbian-dominated officer corps of Yugoslavia’s military wasn’t keen on an alliance with Germany, and they staged a military coup. This led to a Nazi invasion in April 1941. The Yugoslavian military capitulated after less than two weeks of fighting.

After the Nazis occupied Yugoslavia, the Gestapo commenced an intensive search for Rabbi Alkalai, who had anticipated his arrest and fled Belgrade during the German bombing of the city. (Erroneous reports circulated in the world press that he was killed during the bombing.) He escaped to Bulgaria and then to Istanbul, Turkey, before continuing on to Palestine, where he received a warm welcome from leaders of the Yishuv.

While recovering from his harrowing journey in Eretz Yisrael, he lobbied leaders of the Sephardic community to send aid to their beleaguered brethren in Yugoslavia. In the summer of 1942, he traveled to the United States, settling in New York, where he’d remain for the rest of his life.

During the Holocaust and its aftermath, Rabbi Alkalai made use of his affiliation with the World Jewish Congress and membership on the board of the Joint Distribution Committee to work for the rescue of European Jewry. This work was also facilitated by his position with the Yugoslavian government in exile. As Holocaust survivors from the Balkans made it to American shores after the war, Rabbi Alkalai organized reception and rehabilitation and served as refugees’ first address.

He was also instrumental in organizing Sephardic Jewish life in his new country. In 1945 he helped establish the Central Sephardic Jewish Community of America and served as its chief rabbi, as well as the chief rabbi of Sephardic Jews in New York City. He also served as on the New York Board of Rabbis and on the board of Bnai Brith. In his later years, he founded the Sephardic Home for the Aged in Brooklyn, and he moved there himself during his last years. He passed away at age 96 in 1978.

Historian of the Balkans

Aside from his many leadership positions and scholarly pursuits, Rabbi Isaac Alkalai studied Jewish history of the Balkans. This often-overlooked nexus of the Ashkenazic and Sephardic worlds and the Ottoman and Austrian empires was a confluence of ethnic and religious struggles that featured in the history of the Balkans for centuries. In 1928 he published a comprehensive history of Jews in the Balkans in the 18th and 19th centuries, as well as chronicles of Jewish travelers in the region during that period.

Yugoslavian Holocaust

Something often overlooked by many students of the Holocaust is the annihilation of European Jews of Sephardic origin, who primarily resided in the Balkans.

Approximately 80,000 Jews resided in Yugoslavia when the Nazis invaded, and by war’s end only about 14,000 survived. Serbia’s Jews were among the earliest victims of the Final Solution and suffered the nearly unique fate of being killed in their home country, rather than being deported to the extermination centers of the east.

Also unique to Serbia was the fact that killings of Jews were perpetrated by the regular German army, the Wehrmacht, and not the SS. The collaborationist government in Croatia exterminated Jews on its own accord in a brutal fashion; Macedonia’s Jews were deported to Treblinka and in other regions to Auschwitz. Only in Montenegro, Albania, and Yugoslav areas on the Adriatic coast were the Jews spared, as the Italian government declined to deport the Jews under its jurisdiction.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1002)

Oops! We could not locate your form.