Builder of Leaders, Molder of Men: The Eternal Influence of the Alter of Slabodka

| April 11, 2022

Photos: DMS Yeshiva Archives, Slabodka Archives, Chodosh Family, Feivel Schneider, Dr. Shlomo Tikochinsky , Kaunas Regional State Archives, Agudath Israel of America Orthodox Jewish Archives

"We have sustained a great loss with the passing of our teacher, the great light of the Jewish People ztz”l.

This is a man who spent his long life attempting to stay in the shadows, and from that small corner emanated a light which lit up the world! How great are his deeds! We can assert with surety that if not for him then Torah would have been forgotten, Heaven forbid. Behold: those yeshivos which did not benefit from his involvement are now closed, whereas all of the yeshivos in whose establishment and development he invested himself are standing strong and flourishing!”

“Thus the great mashgiach of Mir, Rav Yerucham Levovitz, eulogized his rebbi Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, known to all as the Alter of Slabodka. As Rav Yerucham surveyed the Lithuanian yeshivah landscape of 1927, he accurately described the Alter’s decisive impact on its development over the previous half century.

The Alter’s own yeshivos in Slabodka and Chevron were just the most obvious testaments to his influence. He also opened a branch of the yeshivah in Slutzk, and had a direct impact on Telz, Mir, Lomza, Kobrin, Radin, Grodno, Ponevezh and other yeshivos. It seemed that the growth of Torah at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries was the fruit of decades of planting done by the Alter.

Yet Rav Yerucham couldn’t have known at the time that his words were prophetic as well. A little more than a decade following the Alter’s passing, the world would experience destruction on a scale /previously unimaginable, and the Torah world would once again have to rebuild. As the institutions emerged from the ashes in Eretz Yisrael and the United States, it became evident that the lion’s share of yeshivos and individuals who built them could be traced to the vision of a single individual: the Alter of Slabodka, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel.

How could one man, who passed from This World decades prior, leave such a profound legacy? Who was this person who signed his name as “Hatzafun” — the hidden one — yet whose spirit permeated a yeshivah that produced so many of the 20th century’s Torah leaders? How could a single pioneer’s approach to learning and character development lay the seeds for so many diverse institutions across the globe?

The Talmud Torah of Kelm

Chapter I

To Seek Greatness

Any attempt to describe the legacy of Slabodka and its influence must focus on the life story of its visionary yet mysterious founder.

Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel (also called Nota Hirsch) was born in 1849 in the small Lithuanian town of Rassein. Not much is known about the circumstances of his childhood, other than that his parents were Moshe and Miriam Finkel.

Orphaned at a young age, he was adopted by an uncle in Vilna who sent him to a yeshivah, where he excelled. When Rav Nosson Tzvi was 15 years old, he married Gittel, the daughter of Meir Bashis. Gittel was also the granddaughter of Rav Eliezer Gutman, a leading rabbinic figure in Kelm’s Jewish community. (Her siblings would later adopt the name Wolpert). Following their marriage, Rav Nosson Tzvi continued his studies in Kelm for several years while being supported by his in-laws.

Our story begins to take form in 1868 when at the age of 19, Rav Nosson Tzvi was delivering a speech in his hometown of Rassein. The local rabbi, Rav Alexander Moshe Lapidus, took notice of the young man and suggested that he meet Rav Simcha Zissel Ziv Broide, the Alter of Kelm. (“Alter,” literally “elder,” was a term used to denote an experienced, wise, and revered spiritual mentor. Eventually Rav Nosson Tzvi himself would become synonymous with the term.)

Rav Simcha Zissel was one of the prime figures in the mussar movement, a brainchild of Rav Yisrael Salanter. Rav Yisrael began his movement in the 1840s, when he began to circulate among the shuls of Vilna, preaching mussar teachings focused on character development, interpersonal relationships, and the perfection of one’s inner world of thought and intention. He saw these teachings as essential for a more engaged spiritual and religious life.

As with any new trend, the mussar movement was viewed with suspicion by more traditionalist elements within the Jewish community and the rabbinical establishment. It would take the quiet but unbending determination of Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel to weave this marginalized and oft-derided approach into the very fabric of the yeshivah system.

Rav Nosson Tzvi’s first exposure to mussar was Rav Simcha Zissel. A former colleague’s recollections of the early Kelm years recounts how Rav Nosson Tzvi was drawn into Rav Simcha Zissel’s circle.

“I recall him as a young scholar being supported by his in-laws in Kelm. He was quite knowledgeable and was proficient in Hebrew grammar as well as having a command of German… Around this time the mussar movement began to make inroads in town, as Rav Simcha Zissel delivered mussar talks on Friday night and began to attract a following. Initially Rav Nosson Tzvi was among those who were opposed to this new phenomenon… One Friday we were sitting in the kloiz… and we noticed a marked change in our friend Notta Hirsch. Indeed, he had become a follower of Rav Simcha Zissel and henceforth was completely associated with the Mussarites.”

Two years before he met Rav Nosson Tzvi, in 1866, the Alter of Kelm founded a yeshivah in the town for high-school-age students. The Kelm Talmud Torah (as it was known) devoted the first half of the day to the study of Gemara but also devoted significant time to the study of mussar. Students in Kelm were not judged, as in other Lithuanian yeshivos, by their Talmudic prowess. Instead, Rav Simcha Zissel focused on their character traits and spiritual growth. In an era where yeshivos did not employ mussar mashgichim, this was quite a departure from the norm.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, Rav Simcha Zissel also introduced (with the endorsement of Rav Yisroel Salanter) general studies subjects such as geography, mathematics, and Russian into the Talmud Torah curriculum for three hours a day. Kelm stressed the importance of orderliness of mind and action. An emphasis on punctuality, neatness and methodical self-improvement was a primary focus, and its unique educational philosophy developed future leaders among its students.

It was in this setting that Rav Nosson Tzvi began to spread his wings. Initially employed by Rav Simcha Zissel in 1871 to teach Tanach, he shortly afterward began to deliver mussar shmuessen to the students. Very quickly, it became clear that the young teacher possessed rare oratorical skills, and he developed a uniquely positive rapport with his young charges.

Rav Dov Katz, author of Tenuas HaMussar, described his first meeting with the Alter many years later: “Even in a first encounter, he penetrates you and inspires fear with his great insight and shrewdness.”

In 1876, the Alter of Kelm transferred his Talmud Torah 170 kilometers northwest to the town of Grubin (in current-day Latvia), near the Baltic Sea, with the assistance of the Dessler family. Rav Nosson Tzvi followed. His family did not join him, however, and this would be the beginning of more than three decades where he would live as a parush. It was in Grubin where Rav Nosson Tzvi began to develop his own mussar methodology.

The strong relationship between teacher and student didn’t prevent young Rav Nosson Tzvi from parting ideological ways with Rav Simcha Zissel. Rav Nosson Tzvi believed in a different approach to mussar, and he lacked enthusiasm for Kelm’s inclusion of general studies and openness to Western ideas. Soon he would have the opportunity to implement his own vision.

IN 1877, Rav Nosson Tzvi arrived in Kovno and took a position as the mashgiach of a yeshivah ketanah across the Neiman River, in a small town called Slabodka. Simultaneously, he was involved in the founding of the Kovno Kollel. It was also there that he published Eitz Pri, a pamphlet containing several essays from leading rabbinical figures including Rav Yisrael Salanter, Rav Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor of Kovno, and the Chofetz Chaim. This pamphlet was published in order to publicize the activities of the new Kovno Kollel and to garner financial support. It was to be the only article or publication that the Alter authored in his lifetime.

The introduction he penned to Eitz Pri was, more than anything else, a call to action. Rav Nosson Tzvi saw a crisis taking place before his eyes. His piece described his sense of personal devastation along with his sense of responsibility to act.

The 19th century had brought changes that completely transformed Jewish life in Eastern Europe. Political struggles in Russia, technological advancement, industrialization, urbanization, and emigration were all external forces that loosened traditional norms of the Jewish community. At the same time, many ideological movements such as nationalism and socialism blossomed on the Jewish street, producing a cacophony of voices in the struggle to shape the identity of the Jew in the modern age.

The youth were especially susceptible to this dialogue — and the traditional pillars of mitzvah observance and Torah study seemed, to Rav Nosson Tzvi, on the brink of extinction. Secularization was rampant as the world modernized and offered more options for the “liberated Jew.” Advanced Torah education was rare, as the appeal and opportunities of modern society loomed large. An 1879 report shed light on the demise of organized Torah study at the time, stating that the vaunted Naviezher Kloiz in Kovno, which once housed as many as 170 Torah scholars, had only seven remaining.

Rav Nosson Tzvi was determined to do his part to stem the tide. During his early years in Kovno, he embarked on a whirlwind of activities: the founding of the Kovno Kollel with funding from a Berlin philanthropist named Ovadiah (Emil) Lachmann, publication of Eitz Pri, taking a teaching position in Rav Hirshel Levitan’s yeshivah for young students, founding a kibbutz in Slabodka’s Halvayas Hameis shul, and founding a kibbutz for older talmidim — primarily alumni of Rav Levitan’s yeshivah — in the old Slabodka shul in 1882.

It was also during that time that he helped procure funding (from Ovadiah Lachmann) for the new yeshivah in Telz. In 1883, Rav Eliezer Gordon would move from Kelm, where he was rav, to Telz and become its rosh yeshivah. Telz was the first of many great yeshivos Rav Nosson Tzvi founded or would help bolster. However, of all the myriad institutions he was to be involved with, there was one that emerged as his primary focus: the famed Slabodka Yeshiva.

Slabodka was a pioneering endeavor within the framework of the yeshivah world, as well as a paradigm shift in the goals of the mussar movement. Rav Yisrael Salanter and his students had envisioned a mussar transformation among the Lithuanian lay masses. Mussar houses were to be established in towns, and avodas hamussar was relevant to everyone regardless of age or stage in life. The effort had met with limited success in its early decades, never emerging as a mass movement. Rav Simcha Zissel, the Alter of Kelm, added an educational dimension to this approach by focusing on teaching young children of wealthy families in Grubin, or older married prushim in the Talmud Torah in Kelm. Neither aimed at the kernel of young, full-time yeshivah students.

The Alter of Slabodka envisioned something different and radical for the time — he wished to establish a Volozhin-style yeshivah for older talmidim in their late teens and twenties. It was to be a top-tier yeshivah catering to elite students. At the same time, he wished that the atmosphere of the yeshivah be permeated with the values of the mussar movement. These ideas would be inculcated through an addition to the standard yeshivah curriculum — a mussar seder.

During this half-hour session, students would study a classic mussar work such as Mesilas Yesharim, Shaarei Teshuva, Chovos Halevavos, and the like — and they would do so with great emotion, termed “hispaalus.” They would choose a phrase relating to their character traits and goal of self-improvement and growth, and repeat it many times with great passion, until it entered their subconscious psyche. The resulting heightened awareness would pave the way to growth and change. Though Rav Yisrael Salanter had already promoted this style of mussar study, Rav Nosson Tzvi now added it to the yeshivah curriculum.

The mussar seder was a marked departure from traditional yeshivah study. Some dismissed Rav Nosson Tzvi’s innovation as dangerously skewed, some doubted he would draw serious students, and virtually all wondered what would come of the bold experiment. But Rav Nosson Tzvi prevailed, and the result was a yeshivah that still evokes awe and nostalgia among all who hear the name.

IN 1882 Rav Nosson Tzvi founded the yeshivah of Slabodka. From the start, it was clear that the framework and core ideology of this institution would be a significant departure from Volozhin.

Before opening Slabodka, Rav Nosson Tzvi approached the mussar giants of the era and asked them what approach the yeshivah should take. Rav Yisroel Salanter offered a pasuk from Yeshayahu, and the words, “To give life to those with crushed hearts, to give life to those of lowly spirit,” would soon become the motto of Slabodka’s unique educational approach.

“Gadlus Ha’adam” — the greatness inherent in man — was the theme of the first shmuess a young Rav Nosson Tzvi had heard from the Alter of Kelm, and it became the conceptual cornerstone upon which the edifice of Slabodka was built. Every teaching of the Alter seemed to be a further exploration of the tzelem Elokim of each individual, and his firm belief that man contained a reservoir of potential waiting to be actualized. He taught that mussar has the capacity to unveil and neutralize those forces preventing man from realizing his full potential.

The Gadlus Ha’adam approach induces change by emphasizing what a person can be and how much he can accomplish. It holds up an image of nobility, or royalty, before the striving person, and relates to sin with the attitude of “you’re better than that.”

Gadlus Ha’adam also meant that a person should set the highest possible expectations for himself. And sin was horrific, not because of Gehinnom and dire punishments, but because of the ensuing degradation of Man. The Alter said, “I can’t guarantee that my students will never sin, but I can guarantee that if they do sin, they won’t enjoy it.”

Perhaps as an outgrowth of his belief in the power of the Gadlus Ha’adam perspective, the Alter had a particular affinity for leaders and emphasized leadership traits. He consciously sought out future leaders — and when he found them, he recruited them to his yeshivah and actively developed their inner worlds.

ATfirst, Slabodka did not employ any roshei yeshivah or rebbeim. The students spent their days studying Torah and mussar themselves, directing their questions to members of the Kovno Kollel, who’d occasionally deliver shiurim. Rav Itzele Blazer and Rav Shlomo Nosson Kotler were among those who would speak to the students in learning, while the former, along with his colleague Rav Naftali Amsterdam, delivered mussar discourses to the student body.

The Alter aimed to shape leaders who would understand human nature, and insisted that his talmidim eat with local families on Shabbos: he wanted them to experience family dynamics and observe the interactions between husband, wife, and children.

The end of 1886 was a major turning point for the yeshivah. Following the advice of the Chofetz Chaim (with whom he spent several days over Succos pondering the move), the Alter made the decision to sever the yeshivah’s connection with the Kovno Kollel and turn it into an independent institution.

The first official roshei yeshivah to be appointed were Rav Chaim Rabinowitz (later known as Rav Chaim Telzer), along with Rav Avraham Aharon Burstein, who also delivered a shiur. Newspaper reports indicate that the yeshivah had a registration of approximately 100 students at the time.

After four years in Slabodka, both roshei yeshivah left. Unsure how to proceed, Rav Nosson Tzvi traveled to Brisk to consult with one of the leading Torah figures of the time, Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik, known to posterity as the Bais Halevi. Rav Yoshe Ber recommended that he hire an unknown, private Gemara teacher in Bialystok, Rav Yitzchok Yaakov Rabinowitz (later to be known as Rav Itzele Ponevezher), who had been his student together with the rav’s son, Rav Chaim. “He is a very great man, who can be a great rosh yeshivah,” Rav Yoshe Ber affirmed. Rav Nosson Tzvi then traveled to Bialystok and hired Rav Itzele on the spot.

Though Rav Itzele only remained until 1894, his presence in Slabodka, combined with the closure of Volozhin in 1892, caused the yeshivah to increase significantly in size and stature. And soon enough, the yeshivah would find leadership that would usher it into its golden era.

The Frank family of the Kovno suburb Aleksot was prominent in the mussar movement. The patriarch of the family, wealthy businessman Shraga Feivel Frank, was an early patron of Rav Yisrael Salanter. Following his passing, his wife Rivka followed through on his ethical will to maintain family support of mussar institutions and to marry off their daughters to leading Torah scholars who were mussar adherents.

Two daughters married two of the great students of Volozhin, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein and Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer (the other two daughters married Rav Sheftel Kramer and Rav Boruch Horowitz). In 1894, Rav Moshe Mordechai and Rav Isser Zalman were hired by the Alter to assume the shared role of roshei yeshivah of Slabodka.

That arrangement didn’t last long. In 1897 the Alter responded to a request by Rav Yaakov Dovid Wilowsky, the Ridbaz, by dispatching 14 of his prized students to open a yeshivah in Slutzk. (The group included future Torah leaders such as Rav Nosson Tzvi’s son Rav Eliezer Yehuda, Rav Reuven Katz, Rav Alter Shmuelevitz, Rav Pesach Pruskin, Rav Moshe Yom Tov Wachtfogel, and Rav Yosef Konvitz, to name just a few.) The group came to be known as the “Yad Hachazakah,” and it was headed by Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, leaving his brother-in-law Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein as the sole rosh yeshivah in Slabodka.

Rav Nosson Tzvi’s emphasis on mussar — so much as to include it in the yeshivah curriculum — was a novelty in the yeshivah world, and even within the mussar movement. Not everyone agreed with this innovation, and in its early years, his yeshivah suffered the cost.

Both Rav Itzele Ponevezher and Rav Burstein departed as a result of their opposition to the emphasis on mussar study. They had not come from the ranks of the mussar movement and couldn’t come to terms with the elevation of mussar study to the same level of importance as Talmud study. Their departure signaled that Rav Nosson Tzvi’s new paradigm wouldn’t take root without a significant struggle.

But struggle and opposition often serve to strengthen nascent movements, and that was the case here as well. Several developments combined to form a steady buildup of opposition to Rav Nosson Tzvi’s new endeavor, until it would reach a critical moment.

The first element: In the winter of 1892 the great Volozhin yeshivah closed its doors, and its hundreds of students scattered. Some arrived in Slabodka, and were not very receptive to the mussar approach of the Alter. Whereas at Volozhin there was little supervision, in Slabodka the yeshivah monitored all aspects of the student’s life. This caused tension in the yeshivah and led many students to rebel.

It began with silent protests, but soon devolved into outright revolution. The students removed mussar seforim from the beis medrash and disrupted the Alter’s shmuessen by loudly studying Gemara as he spoke, moves that they claimed led their opponents to escalate the unrest.

Another contributing factor: In 1896 the great Kovno Rav, Rav Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor, passed away. Universally respected and beloved, he served as a great peacemaker as well, uniting factions across Russian Jewry who shared reverence for this Torah leader.

That same year, a new mussar yeshivah opened in Novardok. The approach of its founder, Rav Yosef Yozel Horowitz (the Alter of Novardok), was considered by mussar opponents even more radical than any previously existing models. His unconventional activities and ascetic lifestyle also became fodder for the press and, combined with the student revolt at Slabodka, drew disapproval and public protest.

The opposition soon escalated into an all-out battle against the mussar movement, known as the “Pulmos Hamussar — The Mussar Controversy.” Primarily played out in 1897 in the pages of the newspaper Hamelitz, the battle was conducted by rabbanim from across Lithuania who voiced their opinions for and against the mussar movement’s ideals and educational platform.

To some, it seemed that the very existence of the Slabodka Yeshivah — and perhaps the mussar movement as a whole — was teetering on the brink. How could a fledgling institution withstand such a forceful, prolonged attack?

But the Alter was not one to stand down. He was sure of his approach. Instead, he took a bold step that would alter the course of history.

A young Rav Aharon Kotler was one of the Knesess Yisrael students who regularly would attend shiurim from Rav Boruch Ber in the “rival” Knesses Bais Yitzchak. Once, when they locked the doors before shiur time, the young “Aharon Sislovicher” climbed in through the window to listen to Rav Boruch Ber

Not one to engage in polemics, the Alter simply picked himself up, left the yeshivah he had founded, and began his life’s work yet again in the Butchers’ Shul in Slabodka. Out of 300 Slabodka talmidim in the yeshivah at the time, perhaps a few dozen accompanied him. This small kernel he renamed “Knesses Yisrael,” in honor of Rav Yisrael Salanter.

The majority remained in the old location, and Rav Yitzchak Elchanan’s son, the new Kovno rav, Rav Tzvi Hirsh Rabinowitz, stepped into the vacuum to lead them along with the rav of Slabodka, Rav Moshe Danishevsky. They named the “non-mussar” yeshivah “Knesses Bais Yitzchak,” in honor of Rav Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor.

Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein and the mashgiach Rav Dov Tzvi Heller departed along with the Alter, even though the new heads of the yeshivah had offered the former a higher salary to remain there. Preferring to leave, Rav Moshe Mordechai stated that he opted “to go with the truth, and the truth is with the Alter.”

It was an anticlimactic finale to a pitched battle. Although some tensions remained between the two yeshivos, relations were largely cordial. Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman and other talmidim of the Alter would often refer to this yeshivah as “the other” yeshivah in Slabodka. Later, Rav Boruch Ber Lebowitz became Rosh Yeshivah in Knesses Bais Yitzchak, and students from Knesses Yisrael would regularly attend his shiurim.

In The Life and Times of Rav Boruch Ber, author Rabbi Chaim Shlomo Rosenthal details the “working relationship” between the two yeshivos:

With the knowledge and encouragement of Rav Boruch Ber, many bochurim of Knesses Beis Yitzchak would regularly go to Knesses Yisrael to hear the Alter’s mussar schmuessen. One such bochur was Rav Yitzchak Turetz, who later married Rav Boruch Ber’s daughter.

Rav Boruch Ber had tremendous regard for the leaders of the mussar movement as well as for all who learned mussar. He would say that when his rebbi Rav Chaim (Soloveitchik) would mention Rav Yisrael Salanter, father of the mussar movement, his whole body would tremble.

Initially, however, Rav Boruch Ber did not advocate fixed times for learning mussar during a yeshivah’s daily learning schedule, for that was Rav Chaim’s opinion. As for independent mussar study, outside of the yeshivah’s regular sedorim — Rav Boruch Ber had no issue.

Initial support for the Alter’s new endeavor came from a surprising source. The Chofetz Chaim (who wasn’t a student of the mussar movement) sent 300 rubles to help kickstart the new yeshivah. It wasn’t long before the Alter rewarded the Chofetz Chaim’s “investment” when he sent his student and fellow Kelm mussarite Rav Naftali Trop to Radin to assume the position of rosh yeshivah, propelling the Chofetz Chaim’s yeshivah to even greater heights.

(In one of the more tragic episodes suffered by the Alter during his lifetime, his daughter Miriam suddenly passed away after her engagement to Rav Naftali, whom the Alter greatly cherished. When the Alter suggested his next daughter as a possible shidduch, Rav Naftali refused, stating that perhaps the tragedy was a Divine message that he was not worthy of being the son-in-law of his exalted teacher.)

Support for the Alter’s educational approach came with time as well. The Chazon Ish, who was said to be a critic of the mussar movement, once attended one of the Alter’s shmuessen in Minsk during World War I. Afterward the Alter asked him, “To what do we owe this honor? It is said that you are an opponent of mussar.” The Chazon Ish replied, “True, but I oppose its opponents even more.”

And the institution of a mashgiach, a staff member exclusively tasked to monitor the students’ character development, became such an integral part of the yeshivah structure that no less than Rav Chaim Ozer pronounced that a yeshivah without a mashgiach is like a “bor b’rishus harabim.”

But it took time for Rav Nosson Tzvi’s approach to gain respect among the fiery, opinionated yeshivah students of the era. The Russian Empire was at the time a volatile place for Jews, especially observant Jews. Revolutionary ideas, socialism, nationalism, a deadly wave of pogroms including the infamous Kishinev pogrom in 1903, the Russo-Japanese War and its political fallout — all contributed to an environment of instability. Revolutionary fervor was in the air and this infiltrated all the yeshivos; Slabodka was no exception. The Chofetz Chaim described the rampant secularization of this era citing the pasuk in Parshas Bo: “For there was no house without its dead.”

The instability and splintering that the yeshivah had endured, along with the general tendency of the era’s youth to question authority and accepted norms in favor of sweeping new movements of change, made for some tense years in Slabodka. Rav Nosson Tzvi was aware of his detractors, but for the most part exercised a policy of restraint. His supporters were surprised and disappointed that he didn’t denounce or criticize the rebellious faction. But the Alter believed that ultimately his softer approach would douse the flames and restore peace.

He went to great lengths to show his lack of animosity for the rebels. In 1903, one of the ringleaders of the rebellious faction was drafted into the Czar’s military. Rav Nosson Tzvi hurried to assist this bochur, utilizing his connections with local authorities, canvassing for funds to bribe local officials, and even using hundreds of rubles of the yeshivah’s own funds for this purpose.

Following his release, this fellow continued his position at the helm of the splinter group. The Alter wasn’t fazed. From his perspective, it was mission accomplished: A yeshivah bochur had been saved from the draft and was back in the beis medrash. The fact that he disagreed with his savior’s educational approach was irrelevant.

Following the brutal suppression of the 1905 Russian Revolution, the Jewish street quieted down as well. Revolutionary political activity went underground, and Slabodka emerged from the saga with a stronger mussar identity and with the Alter’s leadership position solidified. Following three decades of struggle, Slabodka was at the cusp of its greatest achievements and glory.

The three greats from Minsk, (L-R) Rav Reuven Grozovsky, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, and Rav Aharon Kotler

Chapter II

Slabodka’s Golden Era

The decade leading up to World War I was Slabodka’s “golden era.” It was during this period that the yeshivah drew many students who would later become Torah leaders. One of the feeder institutions that sent talmidim to the Alter was the yeshivah of Rav Shlomo Goloventzitz in Minsk, and another was a kibbutz of older talmidim at the Katzovisheh (Butchers’) Shul in that same city.

Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky and Rav Aharon Kotler were among the younger talmidim who were recruited to Slabodka with the help of Rav Reuven Grozovsky. The young Aharon Pinnes (Kotler) was an orphan when he arrived in Slabodka. His brilliant and active mind was already under the influence of his older sister Malka, who had strayed from traditional Judaism and was now attempting to pressure her brother to leave his Torah studies and pursue higher education.

Sensing the detrimental effect a steady correspondence with his sister might have on the young prodigy, the Alter of Slabodka took the dramatic step of tasking Rav Reuven Grozovsky to censor Rav Aharon’s mail. (The Alter did this from time to time, when he felt it imperative to counteract subversive influences on his talmidim’s spiritual welfare. It seems that he had commenced this custom back in Grubin, under the employ of the Alter of Kelm.)

The censoring operation continued unabated for a period of two years. By the time Rav Aharon was 17 and had matured, the Alter felt that it was no longer necessary. But when Rav Aharon discovered that his mail had been censored, he was extremely displeased. Deciding that Slabodka wasn’t for him if they freely invaded his privacy and deprived him of his correspondence with family members, he headed to the Kovno railway station and prepared to leave.

Rav Nosson Tzvi was notified and rushed to the station. He persuaded Rav Aharon to return to Slabodka, and thus another future Torah leader was preserved by the Alter’s unique brand of chinuch.

At a memorial gathering held for Rav Reuven Grozovsky many years later, Rav Aharon Kotler rose to speak. He choked up and remained crying at the podium for ten minutes without saying a word. Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky then rose and declared, “I will explain why the Kletzk Rosh Yeshivah feels the way he does.”

He then proceeded to share their Slabodka experiences with the audience, detailing how Rav Reuven played a crucial role in their transfer from Minsk to Slabodka, and how he looked after their welfare following their arrival there. Rav Aharon himself once stated, “Rav Reuven pulled me out of many blottehs (mires).”

In 1910, the yeshivah found itself in its own “blotteh.” The philanthropist Ovadiah Lachmann, who had been the yeshivah’s primary supporter, passed away in Berlin. According to one version of the story (conveyed by Rav Yechiel Perr), the bachelor Lachmann willed a significant sum of money to the yeshivah, but when his siblings heard, they contested the will, claiming that their brother was deranged and no such school in Lithuania existed.

The German court then contacted the Kovno municipality to investigate whether said institution did in fact exist. Inasmuch as the yeshivah was not legally registered as a place of learning (it was technically only a synagogue), the chief of police who came there to make the inquiry was given a bribe by Rav Moshe Mordechai and told, “If anyone asks about a yeshivah in Slabodka, deny its existence.” That is precisely what he did — in this case hurting the yeshivah’s chances to collect the funds. The German court accepted the word of the Kovno police and nullified Lachman’s will.

Rav Moshe Mordechai then traveled to Berlin to try and collect the funding, but as we know from the memoirs of Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, it was to no avail:

“The tzaddik Reb Ovadiah Lachman, the central support of the yeshivah, passed away and bequeathed the yeshivah nothing but the living memory of his distinguished name and the feelings of gratitude and blessing for his admirable charitable acts, which will never be forgotten.”

The Alter felt that every person, being a tzelem Elokim, was worthy of respect. This was especially true of those who spent their day learning Torah. The Alter employed the term “yeshivah mahn” to signify the importance and value of each student.

The Alter insisted that the students in Slabodka appear neat and well-dressed at all times. When Rav Moshe Gurwitz was studying in Slabodka, he once came into the beis medrash with a button missing from his jacket and was admonished by the Alter, “Do me a favor, don’t come back to yeshivah until you get your jacket fixed.”

He would say, “A hole in the sleeve is a hole in the head; a creased and tattered hat signifies a confused mind.” In the early days of the yeshivah, he even had a tailor on the premises to mend garments.

A young student who unbuttoned his shirt and took out his tzitzis to kiss during Shema was reprimanded after davening by the Alter, who said, “We don’t do that here, it’s not nice to undo one’s shirt in public.”

When the Alter’s son Rav Leizer Yudel married the daughter of Rav Elya Boruch Kamai and became assistant rosh yeshivah in Mir Yeshiva, he brought along many of his father’s mussar traditions to the nearly century-old institution. The Mir Yeshiva would eventually adopt the mussar approach, including an orderly outward appearance, with tzitzis tucked inside.

When Rav Meir Shapiro visited Mir, as part of a broader trip to see the great Lithuanian Torah centers prior to building his landmark yeshivah in Lublin, he grew curious when he noticed that the Mir Yeshiva students did not appear to be wearing tzitzis. When he questioned one of them regarding the oddity, the bochur answered in jest based on the mishnah in Taanis 26, “In order not to embarrass those who are lacking them.”

A short time later, a package arrived at Mir Yeshiva addressed to “the students who don’t have them,” courtesy of Rav Meir Shapiro.

When word of its arrival reached the mashgiach Rav Yerucham, he admonished the students, explaining another mussar principle: that one may joke with someone who will understand the witticism, but not with a stranger who will take it seriously.

While the Alter emphasized a dignified appearance and his students were known to dress in fine style, his true focus was inward. He abhorred those who wore their frumkeit on their sleeves and not in their hearts. He would say, “A galech (priest) is frum, he’s outwardly devout; a Jew has to be ehrlich — be honest, be good. That is what a Jew is.”

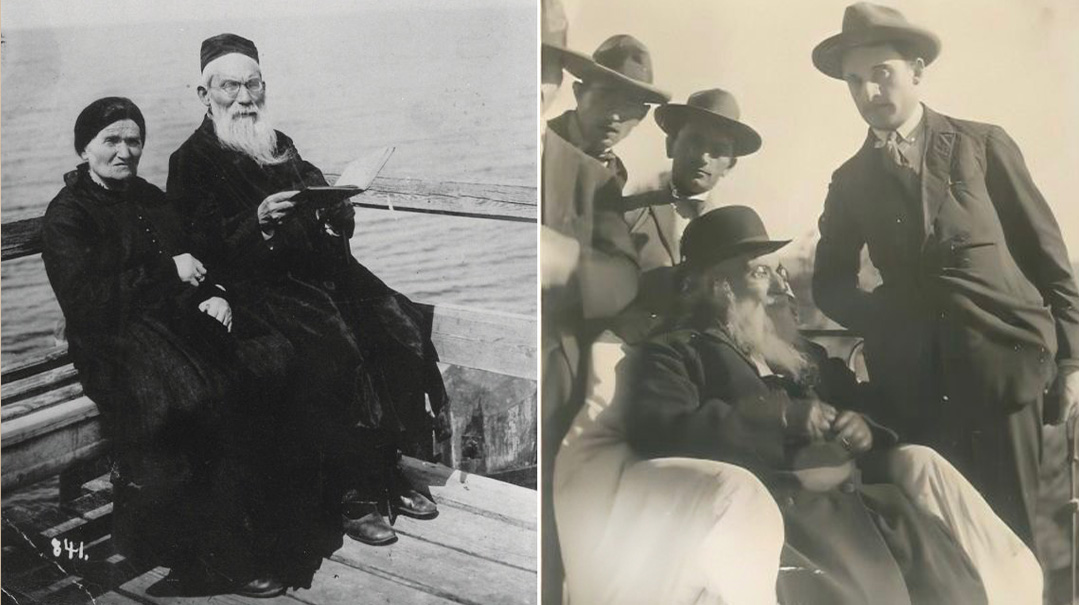

A recently discovered photo of two talmidim of the Alter, (R-L) Rav Yehuda Heschel Levenberg and Rav Moshe Don Scheinkopf who (with the Alter’s encouragement) founded America’s first “mussar yeshivah” in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1923.Some of those who studied there included Rav Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg, Rav Baruch Kaplan, and Rav Sender Linchner

The Alter did not hold an official position in his yeshivah, but he effectively served as administrator — hiring staff and managing the budget — while molding the institution and its individual students to his spiritual standards. His talmidim, however, emphasized his great Torah scholarship as well.

The Alter would go to such great lengths to conceal his Torah knowledge that some assumed that his erudition was limited to Tanach and the mussar topics he quoted in his shmuessen. Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky would get upset when such assumptions were made. He testified that the Alter knew Shas with Rashi and possibly Tosafos verbatim. Rav Yaakov’s brother-in-law and one of the closest students of the Alter, Rav Avraham Grodzinski, added, “Our rebbi was fluent in Tur and Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim, together with the Rambam, the nosei keilim, and all of the achronei acharonim by heart!”

Yet Rav Nosson Tzvi hid both his knowledge and even his studying. He would often utilize the summer months to study undisturbed, away from prying eyes. During the summer he’d review large sections of Shas, and by some accounts he also engaged in the study of Kabbalah during that time.

Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman and Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky both related that they never witnessed Rav Nosson Tzvi learning from a sefer. Yet Rav Naftali Trop did merit to speak to the Alter in learning and experience firsthand his vast Talmudic prowess. Rav Meir Chodosh (later the Mashgiach in Chevron-Slabdoka) used to have a regular session studying Tur with his rebbi. The Alter’s longtime talmid and confidante Rav Yisrael Zissel Dvoretz related that as a young bochur and yungerman, Rav Nosson Tzvi had already gained a reputation as a budding talmid chacham.

But he was renowned most for his control of his character.

In the summer just before the First World War, Rav Moshe Mordechai and Rav Nosson Tzvi decided to appoint Rav Moshe Finkel, who was the Alter’s son and Rav Moshe Mordechai’s son-in-law, as rosh yeshivah.

Rav Moshe was surely fit for the job. A leading student of Torah giants like Rav Elya Baruch Kamai, Rav Eliezer Gordon and Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, Rav Moshe was described by Rav Yitzchak Hutner as also being very advanced in Kabbalah, which he studied in secret sessions with Rav Shlomo Elyashiv (the Leshem).

His greatness in Torah can be illustrated by this episode. Once Rav Meir Simcha of Dvinsk, the Ohr Somayach, spent his vacation in a village close to Slabodka, and Rav Moshe Finkel, Rav Aharon Kotler and Rav Yisrael Zissel Dvoretz went to visit him. When they entered his house, they found Rav Meir Simcha lying on the couch, resting. They introduced themselves and began discussing Torah with him. All four of them enjoyed the discussion so much that it went on for quite some time.

After they left, Rav Meir Simcha told his confidants and members of his family that Rav Aharon Kotler was going to become the “Rav Akiva Eiger of the generation,” whereas Rav Moshe Finkel would be the “Ketzos Hachoshen of the generation.”

Rav Elazar Menachem Shach, who was a talmid in Slabodka at the time, recalled the momentous wedding of Rav Moshe, who delivered a spellbinding shiur on the difficult concept of Harchakas Nezikin in the presence of numerous gedolei Yisrael. He said that after Rav Moshe finished his vort, the great illui, Rav Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan, repeated the whole discourse in grammen (rhyming).

Yet some of the older students resented the decision to appoint 30-year-old Rav Moshe as rosh yeshivah. They saw it as nepotism, and freely voiced their opinions.

Rav Moshe’s first shiur was attended by his father and father-in law, in a sign of ironclad support for his position. The opposition was not deterred, and they organized a shtender avalanche to disrupt the class. The rest of the yeshivah was shocked, and all looked to the Alter to see how he would react.

He remained silent. The volume of that silence was overwhelming.

“I do not know what the Alter did behind the scenes,” Rav Shach later recounted, “but the fact is that the next day the protests were over.”

While some yeshivos are known for a trademark character of trajectory prevalent among their students, the Alter was not interested in a uniform Slabodka “type.” Because of his ability to understand and perfect the varied strengths and skills of his students, he drew a diverse group of disciples who succeeded in a range of roles based on their individual subjective characteristics.

He helped mold great roshei yeshivah such as Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, Rav Reuven Grozovsky and Rav Yechiel Mordechai Gordon, who in addition to their Torah prowess possessed leadership abilities that later positioned them at the helm of organizations such as Vaad Hatzalah and Chinuch Atzmai. He honed dominant mussar figures to shape the next generation in Rav Yerucham Levovitz, Rav Avraham Grodzinsky, Rav Meir Chodosh and Rav Leib Chasman. He developed the inborn abilities of Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, Rav Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan and Rabbi Yosef Zev Lipovitz, all of whom strengthened Torah life in Western Europe. Many communal rabbis and activists in Israel were among his talmidim, such as Rav Yisrael Zissel Dvoretz, Rav Zevulun Graz, Rav Dov Katz, Rav Dov Mayani and others. He produced many of the highest-caliber rabbis that America saw during the interwar years. And the list can go on. No other figure comes close to his incredible impact in attracting and developing future leaders and influencers of Torah learning and life.

Asked the difference between him and the Alter, the Chofetz Chaim reportedly said with his trademark humility, “I write books, he creates menschen.”

The Alter succeeded in “creating menschen” because he possessed a masterful understanding of human nature. Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky would say he had a greater insight into the psychology of man than Sigmund Freud. He had razor-sharp insight into every student; he knew what made them tick, and how to elicit the best qualities from each one.

In the classic biography of Rav Yaakov (ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications), Yonoson Rosenblum shares a powerful story (based on the research of Rabbi Nosson Kamenetsky):

The stress on individuality inherent in the Alter’s vision of gadlus ha’adam permeated Slabodka. Rav Yerucham Levovitz, mashgiach of Mirrer Yeshivah and the dominant figure of the mussar movement’s fourth generation, once visited the Alter. On the first day of his visit, the Alter reproved him so vehemently that the whole yeshivah could hear the shouts from behind closed doors. (Rabbi Ruderman said later that if he had ever talked to a boy in Ner Israel as the Alter did to Rav Yerucham he would not have had a single student left.) This reproof continued day after day for nearly a week.

What had upset the Alter? He felt that Rav Yerucham was so charismatic that he was turning the Mirrer bochurim into his “Cossacks,” each one in Reb Yerucham’s image, rather than allowing each to develop his own unique expression.

A gifted student arrived in Slabodka, and the Alter basically ignored him. Along with him arrived a friend who was more of an average student — not particularly conscientious or serious. The Alter smothered the second one with an inordinate amount of attention, inviting him to his home for meals and having late-night conversations with him. The first grew to resent this treatment.

Years later the first student was sitting shivah for his father, and when the Alter came to visit, he took the opportunity to pour out his heart to the Alter for the years he had received no notice while weaker and less serious students were lavished with attention. He mustered up his courage and said, “You never gave me the time of day, so why are you visiting me now?”

Common sense would have it that the Alter made the simple calculation that his time was limited, and thus he used his precious time on those who “needed him.” But that’s not what he said.

“Your whole world is Torah, your world is yiras Hashem, avodas Hashem. When you desired that I should give you attention, it was the product of your yetzer hara. You wanted to hear praise and compliments to feed your ego. That I was unwilling to do. There’s no value to that and it could even harm you!

“But your friend’s entire identity stemmed from his friends, his social life, and not necessarily what you find in the beis medrash. So when I brought him into my home or when he came to see me, he came to feed his yetzer hatov. He needed excess attention so he’d be open to hearing some Torah, some mussar, so I could try to develop his spiritual side.

“You wanted me for your yetzer hara so I didn’t give it to you. But he wanted me for his yetzer hatov, and that’s why I had to give it to him.”

It’s worth noting that this talmid who was rejected became a rosh yeshivah, while the other became a communal rabbi. The Alter knew how to elicit greatness in each one.

While the Alter emphasized a dignified appearance and his students were known to dress in fine style, his true focus was inward. He abhorred those who wore their frumkeit on their sleeves and not in their hearts. (R-L) Yisroel Bergstein, Eliezer Goldschmidt, Aharon Bergstein, Ephraim Hecht and Moshe Tikochinsky

IN today’s day and age, educators are enjoined to build up students by highlighting their successes. At the time of the Alter, criticism was normal and expected. Still, his brand of criticism conveyed the message that “you are so much more than that.” It enforced a certain vision of latent greatness that could surely be realized, with the proper investment and effort.

During a heart-to-heart conversation with the Alter, a young Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, the future author of the Seridei Aish, admitted that he occasionally forgot to daven Minchah when engrossed in his learning. The Alter recommended that he discuss the matter with Rav Naftali Amsterdam.

So he went to confide in Rav Naftali, explaining that he needed guidance because he sometimes forgot to daven Minchah. Rav Naftali was astonished, and with a horrified look on his face said, “You mean you forget to daven entirely?”

In that moment of fear, Rav Yechiel Yaakov lost control of his words and said, “No, I mean that I forget to daven with a minyan.”

When the Seridei Aish returned to the Alter and shared his misdeed, the Alter cried, “How could you have lied to that gadol?” He then instructed Rav Yechiel Yaakov to return to Rav Naftali and apologize for lying to him and tell him the truth. The Alter even told him, “Do not set foot in my home again until you apologize to Rav Naftali!”

With no choice, Rav Yechiel Yaakov left, and he set out for Rav Naftali’s lodging. Before he got to the door, a fellow talmid grabbed him and said, “The Alter told me to call you — he wants to speak to you before you go in to Rav Naftali.”

Upon his return the Alter said, “I don’t want to cause you more shame; you don’t have to talk to Rav Naftali. I only wanted to cleanse you of the filth of lying, and that was done by your walking to Rav Naftali, trembling at the thought that you had to admit to him that you lied. You are surely cleansed now, and you don’t have to go.”

Beyond the obvious takeaway, there is another lesson to learn from the story. The Seridei Aish had appealed to the Alter for help. Why did the Alter refer him to Rav Naftali rather than provide his own counsel? Because the Alter knew how Rav Naftali would respond, and he could envision the look of horror on Rav Naftali’s face — You don’t daven Minchah? He knew that look of horror would be enough to set Rav Weinberg straight, to cure his defect. That willingness to tap the most effective educational method — even if comes from someone else — is how to produce great people.

One of the methods the Alter used to uplift or send a message to talmidim was the distribution of aliyos. A talmid recalled in an interview with Rav Nosson Kamenetsky:

One Shabbos I was called to the Torah for Chamishi (considered one of the “less prestigious” aliyos) while the important aliyos (such as shlishi) were given to more less important talmidim, so I knew that I was being censured by the Alter. But for what?

After davening, I went up to the Alter and asked what I had done. The Alter responded, “You expect honor? Someone who seeks to be honored by shaming his friend begs recognition for himself?!”

When I replied that I did not know what action of mine he was referring to, he reminded me that ten years earlier, a preoccupied Reuven Minsker [Grozovsky] had walked into the beis medrash one Shabbos morning. He took the jacket sleeve off his left arm in order to don tefillin. The Alter made a quick motion to me to hurry over to Rav Reuven and call his attention to what day of the week it was [Shabbos, when no tefillin are donned]. I did just that — but with a slight sneer that did not pass by the Alter unnoticed. It was for that smirk that the Alter punished me a decade later.

When Rav Simcha Wasserman met the Alter, the latter inquired after his father Rav Elchanan’s welfare, to which he replied, “Not bad.” The Alter asked incredulously, “Is this the way one speaks about a father?! Did I ask you about the condition of the horse in the barn, or the goat in the yard?”

Rav Simcha replied, “This is the very reason I came to Slabodka. People say that here one learns how to speak.” Always one to appreciate a smart retort, the Alter smiled in satisfaction.

The Alter once traveled to Vienna with his son-in-law Rav Isaac Sher. They had to walk along a street where some young men and women were behaving immodestly, and Rav Isaac emphatically expressed his disgust. The Alter’s ears were fine-tuned to pick up even a fraction of insincerity in a person’s reactions. A talmid recalled Rav Isaac’s description of the Alter’s reaction:

My father-in-law shot me a look and said, “Isaac! Are you sure you’re not jealous? Are you quite sure?!”

I was so embarrassed, I felt wounded to the core… but I calmed down and thought to myself — well, he’s probably more correct than I imagined.

On Shavuos, after studying through the night, the Slabodka talmidim were served coffee and cake, and they sang and danced. “Perhaps your real motive in learning all night,” announced the Alter, “was to enjoy the refreshments and the festivities that followed it.”

Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer expressed surprise at these words. In response, Rav Nosson Zvi cited the Gemara’s account of Mar Ukva, who wanted to mourn as an aveil for his brother-in-law, only to be told by Rav Huna, “Your intention is to eat the meal given to mourners” (Moed Katan 20). “If Mar Ukva can be suspected of such motives,” said Rav Nosson Tzvi, “how much more so can we suspect ourselves of them!”

Rav Shach would regularly speak of the Alter’s wisdom and ability to lift up his students in order to develop them into future leaders. When he was studying in Slabodka (1913-1914), the Alter asked him to learn with a fellow talmid who needed a boost.

“I did so,” said Rav Shach, “and the Alter would regularly ask about his progress. One time I answered that the boy hadn’t come to learn with me that day. Immediately, the Alter went to the boy’s lodging and had a long, heart-to-heart talk with him, and soon afterward the student arrived in the beis medrash, ready to resume his learning.”

But the Alter didn’t want him to get discouraged again. He later approached Rav Shach’s study partner with a request. Would the boy do him a favor, he asked, and escort him to the yeshivah every morning, due to his “old age”? The student gladly complied, and of course this greatly augmented his attendance and punctuality.

Beginning in the mid-1920s, the yeshivah embarked upon a massive capital campaign with the hopes of constructing a large, modern building. One of the ways they funded the campaign was by selling “shares” to donors in America. Sadly, the building was only completed at the beginning of World War II and was never used by the yeshivah

Rav Shach would become emotional when describing the Alter’s mussar shmuessen, which were generally delivered on Friday night or the following day before the departure of Shabbos. He described how the Alter would stand on the podium waving his handkerchief about, and speak as one man to another. The audience would crowd around him, and when every seat and even the standing room was filled, people would squeeze onto the benches or stand on shtenders. On a day when a note was hung on the bulletin board warning the students that “it is not permitted to stand on a shtender” because of the danger, everyone knew that a special mussar shmuess would take place that day.

In addition to his regular mussar shmuessen, the Alter gave separate talks to a select group of senior elite students. Among the elite group was the future Chevron mashgiach Rav Meir Chodosh.

Around 1920, a young boy of 14 from Warsaw named Yitzchok Hutner arrived in the yeshivah. A short time after his arrival, the new student was granted permission to join the group of older boys attending the Alter’s talks. Several of the veteran attendees — who had spent years earning their place in the elite group — were astonished and resentful. How could this be? The new boy was so young!

Rav Meir, as one of the closest students of the Alter, asked him the reason behind this seemingly uncharacteristic move. The Alter replied, “Don’t you see that he is a prince, with the regal air of royalty?” And he added, “Tell the others that they have nothing to worry about. They won’t lose out from his presence at our talks.” The Alter was able to discern the makings of a gadol b’Yisrael.

For Younger Students Too

In 1922 the administration of Slabodka opened a feeder yeshivah for younger students. This was divided into three grades, according to age and ability. The yeshivah ketanah was called Ohr Yisrael. Upon the completion of three years, the students were admitted to Knesses Yisrael.

The curriculum of Ohr Yisrael was similar to that of Knesses Yisrael, in that both Gemara and mussar were the primary subjects taught in both yeshivos, but on different levels. Each yeshivah maintained a separate rosh yeshivah and mashgiach. The Roshei Yeshivah included Rav Yitzchak Isaac Hirschowitz, who later became rav of Virbalis, Lithuania, Rav Yechezkel Burstein, famed author of the sefer Divrei Yechezkel, and Rav Yosef Farber, a talmid of the Alter and a grandson via marriage who later became rosh yeshivah in Heichal HaTalmud in Tel Aviv.

Slabodka also had a Talmud Torah that fed into the yeshivah ketanah. Among those who attended the various preparatory yeshivos in Slabodka are Rav Henoch Leibowitz, Rav Elya Svei and yblch”t Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky.

Chapter III

For Generations to Come

IN 1914, the eastern front of World War I brought a sudden transformation of Jewish life in the western areas of the Pale of Settlement. Due to the fact that their homes had turned into battlefields and because of the Czarist government’s suspicions of the Jewish inhabitants as a “fifth column,” many went into exile in the Russian interior. The Slabodka Yeshiva packed its bags and wound up in Minsk for a year.

During this challenging period, the rosh yeshivah Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein’s leadership role came to the fore, and he took responsibility to finance the yeshivah with its 150 students.

The Uvdos v’Hanhagos l’Beis Brisk relates that when Rav Chaim Soloveitchik was residing in Minsk as a refugee during that time, one of his family members fell ill. He immediately sent someone to beg Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein to daven on behalf of the ailing relative. Some found the request puzzling. Weren’t there many more senior and well-known gedolim residing in Minsk at the time? Why Rav Moshe Mordechai? Rav Chaim Brisker explained simply: “Rav Moshe Mordechai learns Torah lishmah.”

The Alter was in Germany when the war broke out, and as a Russian subject, he was taken prisoner. Rav Dov Katz relates the Hashgachah that unfolded during the Alter’s imprisonment. He was later sent with other Russian citizens by sealed train to the other side of the border and eventually rejoined the yeshivah. At the end of the war, a German soldier who had looked after him during his imprisonment in Germany and ensured that he was provided with all his needs met the Alter once again. He revealed his Jewish identity to him and eventually enrolled in Slabodka. (He later joked that prior to the Alter becoming his mashgiach, he was mashgiach over the Alter.)

The yeshivah’s wanderings led it to the heart of Ukraine, in the town of Kremenchug on the banks of the Dnieper River, where it remained for six years. This spanned the balance of World War I, the Russian Revolution, civil war and accompanying pogroms in Ukraine.

The yeshivah was assisted in Kremenchug by local Jews, mainly hardworking Chabad chassidim who were employed in the wealthy Gourary family’s enterprises. Rav Meir Chodosh described the locals as “materially poor, but rich in brotherhood and dedication with a most praiseworthy love of Torah.”

While they were initially stunned to see yeshivah students who were clean-shaven and dressed in short, stylish jackets, the new arrivals quickly proved themselves with their dedication to learning amid the difficult conditions.

Conversely, for some Slabodka students, this was one of their first encounters with chassidim. Rav Meir Shapiro, father of Rav Moshe Shapiro, studied in both Telz and Slabodka and recalled how he seldom encountered chassidim where he grew up:

Throughout the Zamut region [northwestern Lithuania] few chassidim lived. One day word went around Shkudvil (adjacent to Kelm) that a chassiddishe rebbe would be passing through. Many flocked to get their first glimpse of a rebbe. As we watched him eat, a child’s voice was heard exclaiming, “Tatte, dos est! Father, it’s eating!”

Even after the war came to an end, the fighting continued in Ukraine. One thing uniting many of the warring factions was a hatred for Jews, who often became targets. Rav Meir Chodosh recalled one particular frightening incident:

One of the Slabodka students was captured by a gang of Cossacks, who threatened to kill him unless he gave them a huge amount of money as ransom. Pressed to the wall, he directed them to the home of his rosh yeshivah, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein. Those present in the house attempted to collect the desired sum, penny by penny, but the total was far beyond their ability to obtain.

The thugs left the house, dragging the hapless bochur along with them. They were going, they said, to take him out and kill him.

The Rosh Yeshivah acted quickly. Running after the marauders, he shouted at the top of his lungs, “Gevald! Help!”

People came swarming out of every home, joining the Rosh Yeshivah in a kind of bizarre parade, all of them screaming at the top of their voices. The Cossacks became frightened that the Bolsheviks would hear and come out in aid of the victims. Leaving their “prey” behind, they ran for their lives.

Rav Moshe Mordechai had saved the life of one of the great builders of Torah in the decades to come, Rav Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman, founder of Ner Israel in Baltimore.

It was also during that time that 15-year-old Rav Ruderman’s father died. The Alter intercepted the letter with the sad news and kept young Yaakov Yitzchok in the dark. The budding prodigy was working toward completing all of Nashim and Nezikin between Succos and Pesach, and the Alter feared that the tragic news would affect his talmid’s ability to accomplish this goal.

It was told that the Alter explained his rationale by citing the Remah that the reason one informs a son of his father’s passing is in order for the orphan to recite Kaddish. “Rav Ruderman, however, recites Kaddish 24 hours a day! His whole day is a manifestation of kiddush Shem Shamayim of the highest degree. This is the ultimate purpose of reciting Kaddish.” Anything that would take him away from his constant avodas Hashem was therefore counterproductive.

Following Rav Ruderman’s completion of Shas, the Alter called him into his office. The Alter prefaced the sad tidings with a story about Rav Chaim Volozhiner. Rav Chaim had withheld letters from Rav Yossele Slutzker’s family, which requested that young Yossele leave the yeshivah after their store burned down and their father had passed away. Years later, Rav Chaim showed the letters to Rav Yossele, and exclaimed, “Der yetzer hara hut geharget ah mensch — The yetzer hara killed a man, just to take you away from learning — and I didn’t let him!”

With that introduction, the Alter informed him of his father’s passing.

[Authors’ note: This story has been told with Rav Reuven Grozovsky as the protagonist. Our research has shown that it was Rav Ruderman.]

Germany Opens a Yeshivah

AS a result of the turbulence of World War I, the Slabodka Yeshiva was relocated to Ukraine and the original quarters were left abandoned as Kovno and its surroundings were occupied by the German army. The Germans appointed a mayor named Hazah to govern the area while German Army Chaplain Rabbi Dr. Yosef Tzvi Carlebach (who assisted many yeshivos over the ensuing years) was given the mandate over spiritual affairs.

Rabbi Carlebach explained to the mayor that there once had been a great rabbinical seminary in the city, whose students the Russians forced out. Hazah promised to clean, fix and ready the yeshivah building, and to obtain permits for the establishment of a yeshivah there.

And thus, in one of the more bizarre sagas of the First World War, the German Army opened a yeshivah in Slabodka, possibly the only yeshivah in history opened by a non-Jewish military. In 1916 the gates of the new Slabodka Yeshiva were opened, this time by Rav Baruch Horowitz (rav of the Kovno suburb of Aleksot and brother-in-law of Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein) along with Slabodka’s dayan Rav Nisan Yablonsky (later the first rosh yeshivah at the Hebrew Theological College in Chicago).

Rav Carlebach’s brother-in-law Rabbi Dr. Leopold Rosenak obtained funding from German Jews in Frankfurt, and this provided the financial basis for the annual budget for the reopened Slabodka. In 1918 Rav Yerucham Levovitz arrived in Slabodka, where he commenced serving as mashgiach.

On the day the yeshivah re-opened, the remaining Jewish population celebrated by donning festive clothing. Additionally, contributors and Rabbi Drs. Carlebach and Rosenak attended the celebration. A lengthy article published in the German newspaper Berliner Tageblatt emphasized the importance of the opening of this rabbinical seminary of Slabodka.

Decades later, in 1947, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel traveled to America to raise funds in order to reestablish the Mir in Yerushalayim. In New York, he paid a visit to Rav Reuven Grozovsky. One of the individuals who accompanied Rav Eliezer Yehuda was Rav Shlomo Carlebach, later author of the Maskil L’Shlomo and a son of Rav Yosef Tzvi Carlebach.

When the young Rav Shlomo was introduced to Rav Reuven, Rav Reuven became excited and turned to Rav Leizer Yudel, exclaiming, “I can bear witness that if not for the intervention of this young man’s father, the Slabodka Yeshiva would have ceased to exist. Not only Slabodka, but all of the great yeshivos would have ceased to exist without his intervention and efforts to provide sustenance.”

When the winds of war finally quieted and the yeshivah returned to Kovno, it grew both in size and stature, attracting new students from the world over. The Alter founded an kollel alongside the yeshivah, which he called Kollel Beis Yisrael. It was led by the Alter’s son-in-law Rav Isaac Sher, who was also appointed as a rosh yeshivah. Rav Avraham Grodzinski, a prime student of the Alter, began to serve as mashgiach.

Rav Avraham and Rav Isaac would eventually publish the collected mussar shmuessen of the Alter into a compendium entitled Ohr Hatzafun, after his passing. The Alter used to sign his letters with an abbreviated version of his name, “Hatzafun” (the hidden one) as it was his lifelong passion to remain hidden and unseen. It was also the initials of his name Nosson Tzvi Finkel. Fittingly, that hidden light was shared with the world by his two prime disciples.

This duo remained alone at the helm of the yeshivah when, in the mid-1920s, the Alter and Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein made an astonishing announcement: they had decided to move to Eretz Yisrael, where they would open a new branch of the yeshivah in the holy city of Chevron. The Lithuanian government had passed legislation affecting the deferment status of yeshivah students. In order to avoid the draft, Slabodka was prepared to transfer the yeshivah out of the country entirely (eventually the law was rescinded but the yeshivah still went ahead with the move, albeit with just a portion of the students).The Alter transplanted Knesses Yisrael to Chevron in 1925. (For more on the Slabodka Yeshiva in Chevron, see the September 2020 Mishpacha Magazine article entitled “A Bond Sealed in Blood” by Dovi Safier.) In a pioneering operation spearheaded by Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein and his son-in-law Rav Yechezkel Sarna, it became the first Lithuanian-style yeshivah to strike roots in the Holy Land.

The Alter’s impact on the emerging Torah society being constructed in the new Yishuv became apparent shortly afterward. The Lomza Yeshiva soon opened a branch in Petach Tikvah, and it was headed by talmidim of the Alter, Rav Yechiel Mordechai Gordon and the rav of Petach Tikva Rav Reuven Katz. As it turned out, the Lomza branch that remained in Poland was under the leadership of yet another talmid of the Alter, Rav Yehoshua Zelig Roch.

These two pioneering yeshivos wielded an outsized impact on the emerging Torah society of the Yishuv. Following the Chevron massacre of 1929, the Chevron Yeshiva reopened in Yerushalayim, and together with its many offshoots formed a significant component of the contemporary yeshivah world.

Another branch of Slabodka was opened in Tel Aviv under the banner of Heichal Hatalmud. It served as one of the primary yeshivos in the new Yishuv for decades. And it was Rav Elazar Menachem Shach, who considered the Alter to be one of his main influences, who emerged as one of the leaders of the Torah world in the Ponevezh Yeshiva and beyond.

Eventually, the Alter’s son-in-law Rav Isaac Sher would open a Slabodka yeshivah in Bnei Brak, where his own son-in-law Rav Mordechai Shulman, himself a close talmid of the Alter, became the rosh yeshivah.

In Europe as well, even after the Alter’s departure, his impact continued to shape the yeshivah world. The Mir Yeshiva was led in Europe by a talmid of the Alter Rav Yerucham Levovitz, and in Poland as well as in Eretz Yisrael by the Alter’s son Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel.

In the United States, talmidim of the Alter filled various leadership positions in Beth Medrash Govoha (Rav Aharon Kotler), Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim/RSA (Rav Dovid Leibowitz), Yeshivas Ner Israel (Rav Ruderman), Torah Vodaath (Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky), Chaim Berlin (Rav Yitzchak Hutner), Mirrer Yeshivah-Brooklyn (Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz), Bais Medrash Elyon (Rav Reuven Grozovsky), RIETS (Rav Moshe Shatzkes, Rav Yaakov Moshe Lessin, Rav Avigdor Cyperstein), Hebrew Theological College (Rav Nisan Yablonsky and Rav Chaim Regensberg), Yeshivah of New Haven (Rav Yehuda Levenberg and Rav Sheftel Kramer) and other yeshivos. His impact seems to be felt everywhere.

The postwar rebuilding of the Torah world on new continents far from Slabodka can be easily traced almost entirely to one man: Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, the Alter of Slabodka. As astounding as it may sound, the man whose approach was questioned and initially opposed succeeded in nurturing latent leadership skills within a wide spectrum of students who would go on to carry the torch of gadlus ha’adam, illuminating so many cities and institutions with its glow.

On 29 Shevat, 1927 Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel passed away in Yerushalayim. He was buried on Har Hazeisim, next to his beloved son Rav Moshe, who had predeceased him. Though he had passed on to the World of Truth, the groundwork he laid continued to flourish, as the talmidim he had so painstakingly molded were carrying his exalted legacy to further horizons.

Seventy years after he left Slabodka, Rav Shach attended the funeral of his mechutan Rabbi Moshe Bergman, on Har Hazeisim. As they approached the grave, Rav Shach suddenly asked his attendant, “Who is buried in this section?” His escort began naming many great rabbanim who are interred there, but when he mentioned the Alter of Slabodka, a tremor went through Rav Shach, and he requested, “Bring me to the Alter. Ich darf hubben zein zechus — I need his merit!”

The Alter (L) relaxing on a Tel Aviv beach during the final years of his life. Rav Avraham Yaakov Neimark is on the far right

Even after piecing together the facts and chronology of his life, the true essence of the Alter will always remain inscrutable. The challenge is perhaps best captured by one of today’s great biographers of mussar figures, Rabbi Hillel Goldberg:

“A small town has no change for large bills,” said the Alter of Slabodka. This World is a small town. Only Eternity can fully appreciate large deeds — deeds of devotion, of mesiras nefesh. Only Hashem can adequately recognize mitzvos of truly great magnitude.

This World was a small town for the Alter of Slobodka. His eyes were fastened elsewhere. He lived for Eternity. He was above kavod. He was above honors and glory. He was above material satisfaction. He had Hashem’s work to do; he had great disciples to create. He had the future of Klal Yisrael to ensure.

We describe his deeds. As amply, as fully, as we do, we do so inadequately. The Alter traded only in large bills. We, of this world, cannot properly appraise them. We leave the Alter as we began: a mystery. Only Hashem can add up his deeds.

(Right) For more than 25 years, the Alter lived as a parush in Slabodka while his wife Gittel supported the family with the store she ran in Kelm. When he returned twice a year for the Yamim Tovim, he would ask her mechilah for the difficulties she faced as a result of them living apart.

(Left) Toward the end of his life at the Warshawsky Hotel in Jerusalem with talmidim

From early on, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel was referred to as “the Alter.” He was the older mashgiach, experienced, wise and revered. In his quiet and often mysterious fashion the Alter molded individuals, creating a cadre of leaders who would leave an impact on countless lives in prewar eastern Europe and postwar Israel and the United States.

His single-minded focus on developing the individual potential of each of his prized talmidim instilled within them the confidence to continue building the edifice of Slabodka through their own subsequent institutions and talmidim. The wooden ramshackle building in a Kovno suburb has grown into a worldwide network of yeshivos. And the spark of gadlus ha’adam that he ignited continues to shine through generations of his spiritual heirs.

This article would not have been possible if not for the extensive and groundbreaking research of Rav Nosson Kamenetsky z”l, to whose memory the writers dedicate it.

The research and knowledge of the following distinguished individuals was utilized in the preparation of this article: Rav Asher Bergman, Moshe Benoliel, Rabbi Dov Cohen z”l, Prof. Larry Domnitch, Dr. Lester Eckman z”l, Rabbi Dov Eliach, Rebbetzin Shulamit Ezrachi, Yehudit Golan, Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg, Rabbi Reuven Grossman z”l, Mrs. Chaya Sarah Herman, Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky, Rabbi Dov Katz z”l, Rabbi Nachman Klein, Dr. Ben-Zion Klibansky, Rabbi Moshe Kushner z”l, Prof. Samuel Mirsky, Rav Ephraim Oshry z”l, Rav Yechiel Perr, Rabbi Steven Pruzansky, Rabbi Chaim Shlomo Rosenthal, Yonoson Rosenblum, Simcha Schecter, Feivel Schneider, Rabbi Gavriel Schuster, Professor Shaul Stampfer, Dr. Shlomo Tikochinsky, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg z”l, Rabbi Dr. Simcha Willig, Rav Chaim Zaitchik z”l, Nochum Shmaryahu Zajac.

The authors would also like to thank Rav Aaron Lopiansky for taking the time to review this article and provide several key insights.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 907)

Oops! We could not locate your form.