Builder of Dreams

| October 18, 2022Had he known a book would be written about his life, Reb Yehudah (Yudke) Paley would surely have told the author not to waste his time

Photos: Family archives

IT was just two hours before Yom Kippur. The levayah took seven minutes, and then only a sliver of shivah and a flash of shloshim before the Festival of Joy. But that was just the way Reb Yehudah “Yudke” Paley would have wanted it. No fuss, no eulogies, no memorials — just getting on with the music, the simchah of life.

Reb Yudke Paley, who was my own grandfather, was one of those larger-than-life personalities who helped chisel the current face of Jerusalem and practically every other city that established a frum presence over the last half-century, from Kfar Saba to Zichron Yaakov, from Kfar Chassidim to Petach Tikvah and Ashdod, from Teveria to Haifa. He was one of the prime movers of the Israeli yeshivah world as we know it, a bulwark of chesed and a single-handed social services department. A builder of neighborhoods for bnei Torah, and even — as an alternative to secular media — of the very magazine you’re now reading.

Reb Yudke, who was 74 when he passed away, was the son of Rav Hillel Paley, one of the great baalei chesed of the Old Yishuv and the right-hand man of Israeli chief rabbi Rav Yitzchak Isaac Herzog. (In fact, Rav Hillel wasn’t even in the country when Yudke was born — he’d been sent on a mission by Rav Herzog to fundraise for the impoverished Jews of Jerusalem and only managed to return to the Holy Land when his son was three years old.)

Yudke, one of six children, seemed to have his father’s chesed in his genes from childhood. He’d give away his sandwiches to children who were even poorer, and one day as a teenager, he came home from yeshivah with an empty suitcase. He’d given one impoverished bochur a pair of socks, another a shirt… until he had nothing left.

Reb Yudke, known for his sharp business acumen, extensive communal activities, and his vast influence as a primary real estate developer, was actually a seforim publisher before moving on to building development. But really, Reb Yudke’s life was dedicated to the gedolei Yisrael, who knew he was a reliable agent capable of carrying out the most complicated missions during the decades when pressure to secularize was nearly insurmountable. He spent 15 years accompanying Rav Yitzchak David Grossman of Migdal Ha’emek on various missions to save Jewish youth on the fringe, and he became the address for hundreds of bochurim who felt disenfranchised long before the term OTD existed. He’d even take boys home from juvenile court. When he moved to Har Nof, the apartment below his on Rechov Shaulzon 2 became a designated haven for these boys.

Reb Yudke with Rav Shach. The gedolim all knew they could count on him

After the Old City was liberated in the Six Day War, the government had an interest in populating it with secular families, and Reb Yudke knew he’d have to work hard to ensure that the neighborhood return to its traditional roots. He moved there with his own family, was instrumental in securing the Rothschild House for the famed Zilberman cheder (which meant contending with the courts for over a decade until they finally issued a long-term permit), and from the day Yeshivas Aish HaTorah settled in the Old City until it obtained its current building, Reb Yudke conducted all the negotiations on the yeshivah’s behalf.

Over 40 years ago, Reb Yudke Paley became one of the most well-known developers in Jerusalem, out to ensure affordable housing for bnei Torah. He’s perhaps best-known as the builder of Har Nof, whose land was originally slated for secular housing. But he had a vision of a Torah community there, and so he signed contracts with builders, committed to the purchase of hundreds of apartments, and made sure that the neighborhood would be populated by young chareidim desperate for housing solutions.

Reb Yudke was incensed that longtime Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek deliberately took various actions in order to make sure that frum people would not purchase apartments in the new neighborhood. In response, Reb Yudke hired a bus full of Toldos Aharon chassidim and had them wander around the neighborhood, giving secular buyers the impression that they were looking to buy apartments there.

He signed bank guarantees, convinced young frum couples to move in, and did whatever it took to make sure Har Nof would be a religious neighborhood.

I heard from one long-time resident that Reb Yudke offered him a deal he couldn’t refuse. “I’m building a neighborhood, and I want to have a bnei Torah community there,” Reb Yudke told him. “Do you want to buy an apartment there?”

“I have no money for an apartment,” the avreich told him.

“No problem,” he said. “Just pay what you can, and if you have more funds later on, we’ll work it out. The main thing is that you come to live here.”

More than a few bnei Torah got their apartments practically for free.

And places like Yeshivas Beer Yaakov owe their very existence to Reb Yudke, who saved more than a few yeshivos from financial collapse. He had a building in Har Nof that he was planning on selling for a nice profit, but when he heard that Beer Yaakov was in desperate need of a building, he gave it to them.

When one of his buildings collapsed (there were, baruch Hashem, no injuries), it became clear that the responsibility lay with the structural engineer. Meanwhile, the residents were moved into rental apartments at Reb Yudke’s expense, on top of the immense cost of reinforcing the building. But that didn’t stop Reb Yudke from paying the engineer a visit a few weeks later, holding out an envelope with a wad of cash. “I know you’ve just lost your license, and you probably can’t afford groceries. Here’s a bit to tide you over until you manage to work something out.”

If Reb Yudke had become a millionaire, it probably wouldn’t have lasted more than a day.

“There is a man who works hard to make one pair of shoes, and there is another man who sets up a factory that sells a thousand shoes,” said Rav Avigdor Nebenzahl in his short eulogy. “Reb Yudke was not satisfied with selling one shoe — he needed to build an entire factory.”

Reb Yudke was at every intersection between the Torah community and the fledgling state. Helping acclimate recent Bukharian immigrants in the new town of Ashdod

A Different Kind of Biography

Various types of biographies abound. Some contain enlightening anecdotes about the great people in our communities, others are about little-known events and connections from which we can derive inspiration.

Any talented writer who knew my grandfather could probably write both — and that’s what Yitzchak Horowitz has set out to do in his upcoming biography.

But of course, Reb Yudke would be the last person to agree to such a project.

“A book?” he would laugh. “Is that what you’re missing?”

Because why write a book, if you can actually do something? And why write a book about me?

The soon-to-be-published work, therefore, isn’t exactly a personal biography in the classic sense. It is, to a large extent, also the story of the challenges of the Orthodox public over the last seven decades in Eretz Yisrael, seen through the eyes of someone who was there at every juncture and who made a lot of it happen.

The following is the first chapter of the upcoming book. We hope you, too, will find something to learn from it.

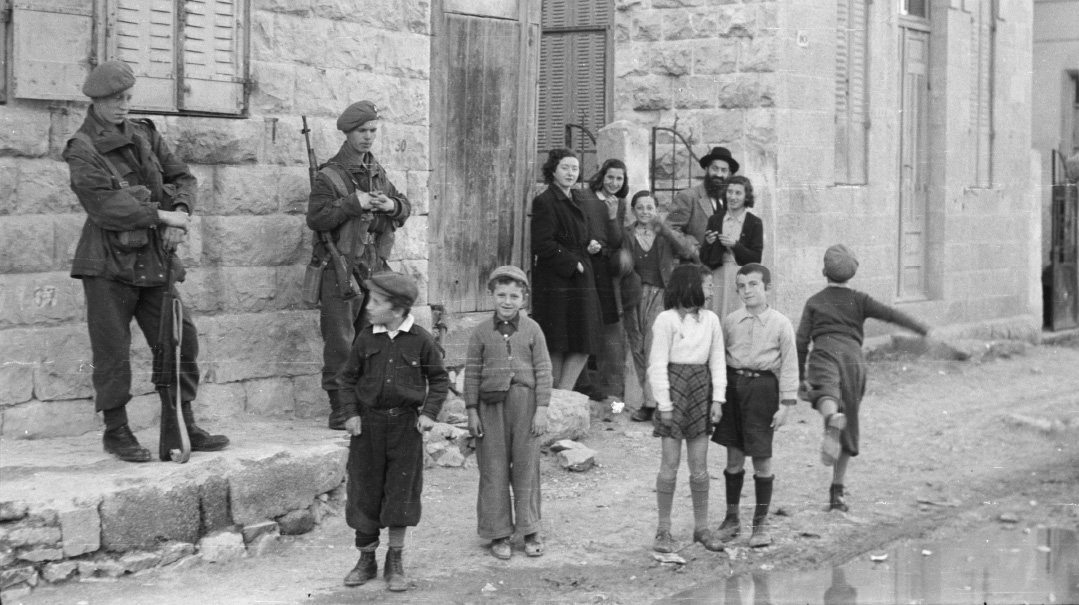

Little Yudke (right) would bury the dead under the noses of the snipers, and never let himself be humiliated by a British soldier

The Boy from Rechov Yonah

Jerusalem, 5708

“Gei tzu di levayah! — Go to the levayah!”

Unnerving explosions. Distant gunfire. Empty streets. The eternal capital of Eretz Yisrael might be its heart, but now it was a frontier by any measure: distant, isolated — and cut off. It was under partial siege, enduring incessant assaults by Jordan Legion forces, the Egyptian army, and the fighters of commander, Fawzi al-Qawuqji. The residents of the city were under constant sniper fire, mortar shelling, and attacks from explosive vehicles detonated in Jewish areas.

And all these problems were compounded by the siege: Even in normal days, Jerusalem was a city ravaged by poverty and lack. When a child’s shoe no longer fit, his mother would cut off the back in order to ease the pressure on his toes. When that wasn’t enough, she’d cut off the front, effectively creating a sandal. Only after that would she consider buying a new pair.

In the best of times, most of the residents relied on charity for their basic foodstuffs, but now, the city was cut off from the oxygen that connected it to the outside world. The Jewish defense force was only partially successful in the battle for Jerusalem. Although it was able to breach the siege and create a contiguous string of neighborhoods in the west of the city, it failed in the east, south and north, losing control of Gush Etzion, Neve Yaakov, and the Old City.

During the bombardments, the residents of Jerusalem took cover in cellars and bomb shelters. The danger in the border neighborhoods was constant — going out into the street meant risking being shot dead by Jordanian sniper fire.

Clearing the dead was very risky, and so was bringing them to burial. Instead, the bier of a deceased person was often abandoned in the street as the pallbearers fled for cover from the bombardments.

That’s why it was so surreal when a group of youngsters gathered around the mittah of one of the victims of the most recent shelling, which had been dropped in the street and abandoned during the levayah — the original carriers had fled every which way.

The Jordanian mortars didn’t deter these children. Neither did the fact that a deceased person is literally dead weight. They were determined to fulfill the mitzvah to the end. With everyone huddled in bomb shelters, they had a plan — they would defy the snipers, take the mittah to a safe place, and then continue the levayah.

And so, these quick, agile children, evading the bullets, lugged the niftar to safety.

“Geit tzu di levayah; geit tzu di levayah!” the children were shouting. They were being led with confidence by a ten-year-old energetic, indefatigable redhead. His name was Yehudah Paley, but everyone knew him as Yudke.

Yudke’s group had a mission: to clear away the bodies that were mounting near the border, which was today’s Shmuel Hanavi street, and transfer them to the taharah room of the Sanhedria funeral home, which was then at the bottom of a demilitarized no-man’s land zone that ran between the Jordanians and the Jews.

But that wasn’t all. These unfortunate niftarim were also the victims of looting, as the Jordanians would pounce on the bodies and strip them of any valuables: money, jewelry or watches. Ten-year-old Yudke and his little group organized patrols to deter the criminals and preserve the dignity of the dead.

Yudke learned about mesirus nefesh from his father, Rav Hillel Paley, a kindhearted Yid and alumnus of the Slabodka yeshivah who came to Chevron and moved to Jerusalem after the riots there. He served as secretary of Chief Rabbi Yitzchak Eizik Herzog, working tirelessly to save refugees from Europe, pressuring the Mandatory government to issue more entry visas to Eretz Yisrael.

One day, when his father was in a discussion with Rav Herzog about saving Jewish refugees, Yudke made a suggestion: “Abba, maybe we should sell our house? This way, we’ll have money to save Jews.”

“And where will we live?” his father asked.

“We can live in a tent,” six-year-old Yudke answered. “We’ll take a tent and put it on Rechov Shivtei Yisrael.” At the time, Shivtei Yisrael was an empty lot where homeless people dwelled.

Reb Hillel had no idea where Yudke was when he was out rescuing niftarim, as mortars whistled overhead and Jordanian fire raked the streets of Jerusalem. Why was he not in the bomb shelter with everyone else? But it was impossible to pin Yudke down. One second he was next to you, the next second elsewhere.

“Where were you?” Reb Hillel would ask him.

“Don’t worry, Abba. We were doing mitzvos. Hashem is watching over us.”

Yudke as a teenager in one of the early classes in Yeshivas Ohr Yisrael, standing behind his rebbeim, Rav Yaakov Naiman and Rav Yosef Rozovsky

Everyone’s Best Friend

Reb Hillel had six children: two sons and four daughters, all living together in a small, two-room apartment on Rechov Yonah, near the Chevron yeshivah building. Yudke was the fourth. The older brother, Avremke, was considered an illui as a child. A short time after his bar mitzvah he was tested on four hundred daf Gemara. But Yudke never felt like he was in his brother’s shadow. Everyone knew Yudke, the cheerful, clever, witty child with green eyes that always sparkled with humor had his own talents. He was gifted with a warm heart, a mature sense of justice, and an uncanny ability to step up to help anyone in need.

“Everyone loved Yudke,” related his friend from those days, Rav Moshe Chodosh ztz”l, rosh yeshivah of Ohr Elchanan. “It wasn’t possible to fight with Yudke. I remember how, already as a young boy, he was very sensitive about respecting others. He would come to the aid of any underdog, but for himself, he always had such a simple demeanor and didn’t care. But those weren’t easy days, especially for children. It was wartime — there was austerity, and kids just fought. But not Yudke. He always knew how to smooth things over, a trait that characterized him throughout his life. He was always busy helping someone with something, and everyone loved him and admired him. Everyone was sure that he was their best friend.”

Attorney Menachem Yanovsky lived on Rechov Hoshea, the next street over. “We would meet and play together, either with pebbles or other things we turned into toys. Everyone was very poor, and the games needed some improvisation. We didn’t have a ball, so we used rags and orange peels.”

The acute poverty made it necessary to find creative solutions not only for children’s toys, but also for more basic things, like food. Yudke and his friends had solutions for this as well: They would go to the shul in the Bucharim neighborhood, where one of the children would say Kaddish, in the hope that people would assume he was an orphan and give him a bit of money to buy a portion of falafel.

But the real creativity the economic situation brought out in Yudke was in the many opportunities it presented for doing genuine chesed.

“In Jerusalem there was grinding poverty,” one of his acquaintances from those days recalls. “We lived so minimally. But there were those who didn’t even have that little bit. They couldn’t even bring a slice of bread to cheder. Yudke was the one who gave them his own piece of bread, even if they didn’t ask him.”

Yudke attended the Yavneh Talmud Torah, founded by Chevron rosh yeshivah, Rav Yechezkel Sarna. One day, Yudke returned home from cheder, his clothes stained with jam. When his mother asked him what had happened, he said that he had gotten dirty while eating his sandwich. Later it emerged that indeed he got dirty from the bread, but not because he ate it. A few of his classmates had come that day without food, and so Yudke divided his bread into small pieces, wiping his little hands on his shirt.

But it was only because Yudke had nothing to eat that day that he felt compelled to keep his chesed a secret. His parents encouraged him to bring home friends and he’d often ask his father for a bit of money for them. Reb Hillel would accede, encouraging his son to continue with his acts of chesed and giving.

“He was just a kid, but already he was working for the klal,” Yanovsky relates. “Any boy who needed help knew the address: Just reach out to Yudke.”

With plans for Har Nof. Reb Yudke was so incensed that mayor Teddy Kollek was trying to prevent frum people from moving in that he took matters into his own hands

Over Spilled Milk

“At the time, in Geulah, there were families who did not observe mitzvos, and lots of fights broke out between them and us,” remembers one friend from those days. “At one point, the secular children started taunting us, calling us ‘bank-kvetchers,’ idle bench-sitters who did nothing and had no strength. But Yudke didn’t get drawn into the fight. Instead of arguing, he suggested that we play ball against them. We played, and won, but in the end that didn’t really help us either. They found other faults in us, claiming that we won because we weren’t learning enough. But they still gained respect for Yudke, even though he was just a little kid at the time.”

That little kid knew how to deal not only with playground fights, but also with British soldiers in uniforms. Once, his mother sent him to get milk. Yudke got distracted, and by the time he got back, the curfew had already taken effect. A soldier saw him on the street, gave him a kick, and Yudke fell, spilling the milk.

But Yudke didn’t cry over his spilled milk. Instead, he took his revenge: He waited in a hiding place for the British patrol to pass and then took the ultimate weapon — a little rock — and aimed it directly at the window of the vehicle.

The vehicle screeched to a halt. The stunned soldiers emerged, red-faced and breathless, to hunt down the little saboteur. But Yudke wasn’t there anymore.

It didn’t bring back the milk, but he wasn’t going to let a British soldier get away with humiliating him.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 932)

Oops! We could not locate your form.