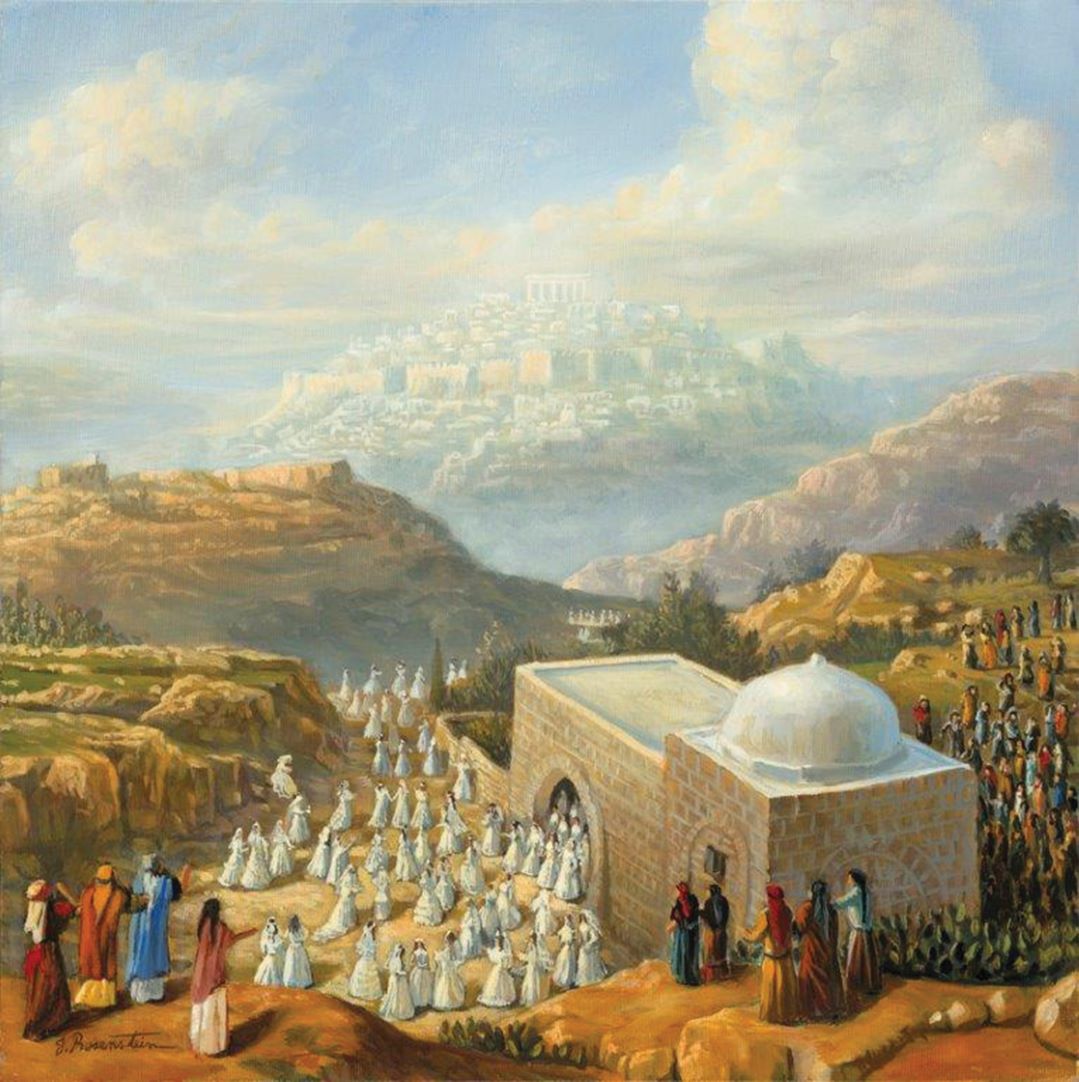

Yossi Rosensteins traveling exhibit transforms all the emotions and yearning associated with Kever Rochel into a visual showcase

CLICK ON THE GALLERY BELOW TO VIEW THE PAINTINGS OF KEVER ROCHEL

I

n Parashas Vayishlach, we read about the death and burial of Rochel Imeinu “on the way to Efrasa… And that is where Yaakov buried her and placed a headstone over the burial site” (Bereishis 35:19–20). Rashi there explains, “that is the headstone of Rochel’s burial site to this day,” as a marker for Jews going into exile and — may it happen speedily — “coming back to their borders.”

For artist Yossi Rosenstein, those words became a calling. His current traveling exhibit transforms all the emotions and yearning associated with Kever Rochel into a visual showcase.

Rosenstein was a promising young graduate of Ponevezh and Chevron yeshivahs when he considered entering what he thought would be the glitzy world of business — he had already been accepted as a member of the diamond bourse in London. But an inside voice told him that trajectory would kill the yearnings of his soul. Being honest, he realized he wanted to live a life of spirituality, not just to visit it once in a while. So he decided to abandon the promise of glitter and instead invest his energy into his G-d-given talent: creating a synthesis between what he calls the heichal haTorah and his special gift for art and creativity.

Jerusalem-born Rosenstein, 64, a ninth-generation Israeli descended from a prominent Slonimer chassidic family who today lives in Bnei Brak, taught himself to draw and paint when he was a bochur, and had his first exhibit when he was just 21 — in a Tel Aviv gallery whose proprietor was so captivated by his unusual style that he agreed to keep its doors closed on Shabbos.

Look at a painting in the unique genre Rosenstein developed and you’ll have to look again: What looks like a crowd of people is really a cluster of candles. What looks like a group of Jews davening is really an intertwined mass of tefillin. Rosenstein’s initial concept was to avoid drawing real people or giving specific personification to Torah characters — as dictated by some halachic authorities — and use stone, wood, and wax instead. But what emerged from that stricture is a unique style that draws in the viewer with such intensity that he feels he can connect to the innermost intentions of the Torah passages or mystical ideas represented.

Interpreting ancient truths to modern connoisseurs means combining modern symbolism with the techniques of classic art — an accomplishment that has become the benchmark of a “Rosenstein.” Rosenstein’s style became popular among budding artists within the Bais Yaakov system, and at the behest of rabbanim who wanted girls to learn art in a kosher environment, he created an art school that enabled them to learn popular techniques without having to stumble through foreign or impure art.

Until the Redemption

An artist’s life is never routine, and you can forget about pinning most of those talented folks down to predictability. But sometimes a project is so important the artist stays with it for months, or even years. For Yossi Rosenstein, the flagship Kever Rochel Project was one such an undertaking. Rosenstein created 22 intricate, multilayered works relating to the kever, its place in history, and the mystery and mystical energy surrounding it. Each painting bears his unique stamp — the candles, the interplay of light, the connection and interface between past, present, and future.

“I decided to create 22 paintings, the number of letters in the alef-beis, each one of which would reflect a different angle relating to Rochel Imeinu and her relationship to her children — to every Jew,” Rosenstein explains. “Until the final painting, which shows all of Am Yisrael united with Rochel Imeinu at the time of the Final Redemption.

“I chose Kever Rochel because it serves as a spiritual lighthouse in Israel. People from all over the world dream of coming there,” he relates. “It’s the only one of all the holy sites mentioned in the Torah, in the Navi and in the Midrash, as a place for tefillos and yeshuos. Throughout the generations, Arabs and Christians also visited the site, aware of the power of prayer there. I once read a document from a Christian pilgrim who visited Eretz Yisrael in the 15th century, relating that the local women would come to Kever Rochel and gather stones from around the structure to make amulets for an easy birth.”

Today’s road to Kever Rochel is surrounded by a security detail, but, says Rosenstein, the pilgrimage was never easy. In his research, he found original writings in which visitors described having prayed at the site more than a thousand years ago, and the many dangers that were present on the route to Beis Lechem. As he researched further, Rosenstein discovered that the site’s external appearance has changed over the years. Historical records alternately describe one headstone plus eleven stones, four pillars topped by a dome, and eleven stones joined together that became one large headstone, covered by a greenish paroches. Throughout the years, there’s been documentation of extensive destruction, perpetrated by residents of the surrounding Arab towns. But they would only destroy the structure, without desecrating the actual headstone, which they took care of and preserved.

In Rosenstein’s paintings, Kever Rochel transcends many different time periods — but none of them are for sale. Instead, they’ll be displayed in a wandering exhibit scheduled to appear at hundreds of Jewish centers around the world. Because, he says, “Rochel Imeinu is about all of us.”

CLICK ON THE GALLERY BELOW TO VIEW THE PAINTINGS OF KEVER ROCHEL

Click here to contact Yossi can via his website

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 537)