Brisk: The Mastery & the Mystery

With its own lexicon, its own unspoken rules, and its uncompromising value system, what is the secret of Brisk — and how has it managed to capture the hearts and minds of a nation?

Photos: Mishpacha Archives

One hundred years after the passing of its founder, the pull of Brisk is strong as ever, drawing the most valiant soldiers of the Torah world to a dimension where little has changed. With its own lexicon, its own unspoken rules, and its uncompromising value system, what is the secret of this dynasty — and how has it managed to capture the hearts and minds of a nation?

Asher Soloveitchik was in my dirah!

Not as a rent-paying member of the dirah, but l’maiseh, he was inside.

A son of Rav Dovid Soloveitchik, a grandson of the Brisker Rav, was sitting inside our dirah, on a bed covered with blue plaid linens bought in Marshall’s, near a small cubby with Pringles and an ArtScroll siddur, schmoozing with us.

Our little group of bochurim was heady with a sense of accomplishment, of having finally arrived. Months after we joined the yeshivah of Rav Dovid, determinedly filing away every little bit of Brisker lore, eagerly lapping up scraps of history, and of course, reveling in its Torah — how many times did we learn that first Brisker Rav on Lishmah, even before booking airline tickets? — we’d become entrenched enough in this world of Brisk that our rosh yeshivah’s son had come in to chat.

At the time, he was still a bochur: Asher of the clear, Brisker eyes, nuanced smile, and disciplined walk.

We knew that it was strange that he’d veered from the precise, usual path from the yeshivah on Rechov Pri Chadash to his home on Rechov Amos, and come in to our one-room dirah on Rechov Malachi, (which, alas, is no longer a dirah, or even the real-estate tivuch it became after that; it’s been swallowed up into a colorless extension onto somebody’s porch.)

We knew this was a one-time occurrence; tomorrow it would be a buzz in yeshivah and it would never happen again. (It didn’t.)

We were like a group of fresh political interns suddenly come face to face with the vice president in the hallway. We’d taught ourselves to roll our reishes, when we said “the Rav” we were no longer referring to the shul rabbi of our youth, we’d learned to be wary about hechsherim not called Badatz Eidah Chareidis, and we dreamed of marrying girls who would walk the chickens and oversalt the meat and all the other kitchen terms we’d heard of, but never seen.

Now one of the royal family was among us, close enough to touch.

We racked our 19-year-old brains for the perfect question to suit the occasion, scrambling. The genie was out of the bottle and we couldn’t think of a single wish.

Someone finally asked a question that was vague, but at least it worked, given our choppy, neophyte Yiddish.

“Voss is Brisk?”

Asher looked up, intrigued by the question.

It wasn’t a new one.

The traditional answer is that Brisk is marked by the rigorous, systematic, precise, analytical approach to a Gemara, the splitting of ideas into “two dinim,” differentiating between the Talmudic concepts of gavra and cheftza. That thought process doesn’t just answer questions and contradictions, but rather, it exposes any inherent flaws.

Brisk, to others, means a laser-sharp focus on truth, with no distractions — not in halachah, not in hashkafah, not in life. It’s a fearless, agenda-free perspective.

But over the years, it had become a way of life, a community of its own — so what did it mean, to be a Brisker?

The question sat there, Asher contemplating, the rest of us predicting where he would go with it.

We knew that cerebral agility had something to do with it. So many of the legendary Brisk stories revolved around the lightning-quick grasp and sharpness of the protagonists.

And that ability goes right back to the root, to Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, who is considered the patriarch of the Brisker dynasty. When Rav Chaim was a child, he learned along with a friend. An older scholar asked the friend which of the two talmidim was more gifted. Who was learning better?

The friend confidently replied, “If I say he understands better than I, I would be lying. And if I say that I understand better, I will appear a baal gaavah.”

It seemed a brilliant answer, the final word.

Little Chaim Soloveitchik didn’t hesitate. “Now you’ve managed to be both a baal gaavah and a liar.”

In a shiur, his grandson Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik of Boston maintained that all the astuteness of Brisk, the intelligence and keen insight, were tools used towards the chesed of Brisk, the compassion and kindness of its leaders: They fused that insight with their soft hearts, and this way, they were able to help the downtrodden.

That was the endgame.

In Brisk, he recalled, the rav’s home was public property. People would eat and sleep all over, using the home as their own. Some would famously post signs on its walls, as in a public space, announcing services or seeking lost objects.

Once someone described the scene in that home in front of the Brisker Rav (known as Reb Velvel), Rav Chaim’s son.

“The whole house was a reshus harabbim, people considered it public property,” the person commented.

“No,” Reb Velvel quickly replied, “that isn’t accurate, because even reshus harabbim has dinim, laws governing behavior there. A person may not lie down to sleep there, for example, because pedestrians have a zechus of passage there; my father’s house was more like ‘reshus hayachid for Klal Yisrael’ where every single individual had rights!”

Among the features of life in the rav’s home was the occasional appearance of a new baby. These were children of parents who couldn’t or wouldn’t care for them, so they became the rav’s charges. Rav Chaim and his rebbetzin assumed responsibility for these children, and they hired wet nurses to feed the helpless infants.

One week, a nurse was late in being paid and she burst angrily into Rav Chaim’s room, shouting that she would not feed the frantic baby until she got paid. Rav Chaim rose and immediately apologized for the misunderstanding, calmly assuring her that he would get her money right away. He returned a few moments later with the money, and the woman thanked him.

As she headed to the door, Rav Chaim stopped her. “Can I ask you a favor? You were justified in your anger, but I would nevertheless ask that you wait a few minutes before feeding the baby. You see, as long as you feel anger, that hysteria will be transferred to the baby. Why should the baby suffer because of my mistake?”

That too, is an answer to what defines Brisk: intelligence that goes beyond the beis medrash, the brilliant rationale used to calm a crying baby.

Reb Velvel’s son Rav Meir Soloveitchik had his own definition for what Brisk is all about. The weekly Shalosh Seudos at his home, Chazonovitch 3, was known as a central time for transmitting Toras Brisk.

Behind the humble door of his apartment, Brisk was preserved in its original form — starting with the chesed. The poor, lonely, and destitute, the down-and-out and emotionally disturbed: All found their way to the home where Rav Meir and his family adopted them.

Shalosh Seudos was a special time. His brother Rav Dovid and his nephew Rav Avrohom Yehoshua delivered their Chumash shiurim on Friday night or Motzaei Shabbos, but Shalosh Seudos was the time when Rav Meir, with the radiant face and large eyes, he who so resembled his father, would speak.

What is Brisk?

He once remarked that while people tend to marvel at the kishronos, the cerebral dexterity of Rav Chaim, they miss the fact that Rav Chaim’s greatness wasn’t a product of his intellect. Rather, Rav Meir said, Rav Chaim became Rav Chaim because of two ingredients: real ameilus b’Torah and real aniyus.

Toil and poverty.

And Rav Meir shared a family tale.

Reb Leibe’le Kovner, a progenitor of the house of Brisk, was a poor man — so poor that he had no money for cholent on Shabbos. His wife shared her embarrassment with him: The women of the town would bring their cholent to the communal oven every Friday, and they noticed her absence. Poverty in privacy was one thing, but did the whole town have to know?

Reb Leibe’le suggested that she fill a pot with water every Erev Shabbos. Then, she would cover the pot and affix a cloth to mark it as her own, so she too could bring a pot to the communal oven. “The derech of people is not to open a covered pot,” he told her.

Rav Meir concluded the story. “Reb Leibele and his rebbetzin only had hot water for the Shabbos seudah — and from that came a Reb Chaim, all the Torah of Brisk! Brisk is about toil, about not looking to make things easy!”

And that toil was a conscious decision.

When Rav Chaim was ready for marriage, his father, the Beis HaLevi, deliberated between two shidduchim. Both girls were of exceptional character, but one came from a wealthy home and the other came from a home heavy in scholarship, but without much money.

(When one of the other sons of the Bais HaLevi got engaged to a wealthy girl, the new father-in-law gave him a large sum of money. The Bais HaLevi worried about his son becoming arrogant as a result of the generous dowry. “It’s not because you’re such a big lamdan or talmid chacham,” the Bais HaLevi told his son, “it’s only because of your yichus, your impressive lineage.”

“If it would be because of the Tatteh,” the chassan immediately replied, “then I would have gotten much more.”

The Bais HaLevi smiled. “It’s because of your yichus, and you takeh should have gotten much more: but you came in the middle and made kalya!”)

The Bais HaLevi asked his own rebbi which shidduch option was better suited to Rav Chaim. His rebbi advised him to choose the wealthy girl, and thus enable his son to learn in serenity. Rav Chaim’s mother thought differently. The poor girl was a daughter of Rav Refoel Shapiro, a son-in-law of the Netziv. “And if Chaim’ke sits behind the oven in the Volozhiner Yeshivah and speaks in learning with the bochurim,” she said, “he’ll feel warm in This World and the Next.”

Rav Chaim would join the faculty of Volozhin after his marriage to Reb Refoel’s daughter, but every so often, he would go sit behind the oven and speak in learning with the bochurim — to give pleasure to his mother.

So what is Brisk?

Toil, poverty, brilliance, kindness—

But on that spring day over 20 years ago, Asher Soloveitchik had a different answer.

“Brisk,” he said in a sing-song voice, “Brisk meint…”

He waited a heartbeat.

“Brisk meint shveiggen.”

Brisk means keeping silent. Knowing what not to say. Respecting each word.

(One of the stories passed around yeshivah: On Chol Hamoed, Rav Yankel Schiff, son-in-law of the Brisker Rav, took his sons on Yom Tov visits to the uncles. They sat by Rav Dovid, but no one spoke. After several minutes of complete silence, one of the Schiff boys turned to his father. “Tatte, genug geshviggen bei Feter Reb Dovid, lommir gein shveiggen bei Feter Reb Meir, Father, we’ve been quiet by Rav Dovid for quite a while, now let us go be quiet by Rav Meir….”)

And then Asher smiled, because he hadn’t only answered the question, he’d done it in a way that gave us pause — made us think that maybe he was begging off answering at all.

Sharp move.

But by that time, he’d slipped out, safely back on Rechov Amos…

The silence of Brisk isn’t just a holy practice, it’s a source of Torah itself.

Representatives of the Brisker Chevra Kaddisha came to the home of the Brisker Rav one day together with another man.

They wanted the Rav to adjudicate their respective claims. A person had died, and shortly after that, a second person had passed away. Rather than follow the time-honored “first-come-first-served” policy mandated by halachah, they buried the second niftar first. Now, a relative of the first niftar was there, and he wanted an apology from the chevra kaddisha for this violation.

The Rav heard the story, and he removed a Rambam from the shelf. After looking inside for a moment, he informed this relative that while the chevra kaddisha was certainly wrong, they didn’t owe him an apology. The Rav promised to discuss their actions with them, but made it clear that the man had no claim to an apology.

When the gentleman left, the Rav explained his decision to Rav Chatzkel Abramsky.

There is a general rule that one should not pass up a mitzvah, and that obligated the chevra kaddisha to bury the first niftar before the second. One who violates this principle hasn’t wronged his fellow man; his offense is bein adam l’Makom. But perhaps, the Rav continued, there is a special din of ein ma’avirin al hamitzvos when it comes to a niftar, due to kavod hameis? That’s why he’d looked in the Rambam, because if that would have been the case, then the claimant — as a relative of the first niftar — certainly deserved an apology. Not finding a hint of this din in the Rambam, the Rav ruled that no apology was necessary.

Later Rav Abramsky would repeat the story, and remark that others know how to deduce halachos from what the Rambam says — but the Brisker Rav learned halachos from what the Rambam did not say!

The holiness of words… and the holiness of silence.

Rav Moshe Mordechai Shulsinger was orphaned as a bochur. He was learning well, but some well-meaning relatives insisted that he leave yeshivah and start working in order to help support his mother. Devastated by the thought of leaving yeshivah, he went to ask the Brisker Rav for advice.

The Rav heard the question, and then ruled. “Di Eibeshter veht helfen.”

The bochur appreciated the brachah, but he needed practical guidance. Should he listen to his relatives or to his soul?

The Rav explained his answer. “To say that a bochur should leave the beis medrash… I can’t say that. To say that a son shouldn’t help his widowed mother, an almanah… I can’t say that. So if I can’t say this way or that way, then it’s muchrach, inevitable, that HaKadosh Baruch Hu will help.”

There is the tefillah of Brisk.

When Rav Dovid Soloveitchik was raising funds for the “neiye binyan,” his yeshivah’s current home in Gush Shemonim after many years of being housed in the Kerem Avraham shul in Mekor Baruch, the rosh yeshivah looked around at the yungeleit after shiur one day.

“It’s your fault that the binyan isn’t up already,” he said.

It was a surprising comment, for who like the rosh yeshivah knew that they were all struggling to make it through the month? He preached mesirus nefesh and lived mesirus nefesh and they strived to emulate him. Who had money to help?

“Nisht mit gelt,” he clarified, “not with money. But why aren’t you davening for me?”

Money is just money, Rav Dovid was saying, but tefillah is reality: that’s how buildings get erected and paid for.

His brother Rav Meir Soloveitchik would speak about a revelation he’d experienced. When the family, the Bais HaRav, arrived in Eretz Yisrael in 1941, they saw a different sort of tefillah.

In Brisk, he would say, we also saw Yidden daven — but in Yerushalayim we saw Yidden who understood that there was no other way.

Rav Meir told talmidim that in the Yerushalayim of those years, there was a constant water shortage — not only at summer’s end, but throughout the spring as well. “By Shavuos, finding clean water to drink was already a challenge, and the only solution for thirsty people was tefillah. So Yerushalayimer Yidden got used to davening as a means of survival. It was as natural as turning a faucet is today; tefillah brings water, and they understood it. Since then, they have it in their blood.”

This too is part of the family legacy: Go to Kever Rachel and often, you will see a child of Brisk, a young boy in a dark cap, peyos hanging down in front of his ears, or maybe his straight-backed father, reading words from Tehillim clearly, precisely. Perhaps you will even see Rav Dovid himself, weak, frail, seeming to find new strength from the open Tehillim before him.

t’s hard to point to an “heir,” any definitive successor to Rav Chaim and his path. There are so many prominent rabbanim, roshei yeshivah, and maggidei shiur who carry the name or the aura of Brisk. Along with the Brisk Yeshivos in Geula and Gush Shemonim, there is one in the Old City. Rav Chaim Feinstein, a grandson of the Brisker Rav, is rosh yeshivah of the Ateres Shlomo network, and Rav Moshe Meiselman, whose mother was a daughter of Rav Moshe Soloveichik of RIETS, heads Yeshivas Toras Moshe, and Rav Boruch Soloveitchik — son of Rav Moshe of Zurich — is rosh yeshivah of Toras Zev in Yerushalayim. There is a Brisker Yeshivah in Chicago, and its founder Rav Ahron Soloveichik’s son, Rav Eliyahu, is a rosh yeshivah at Beis Medrash L’Talmud/Touro’s Lander College for Men, and his brother Rav Chaim is a rav of Ohr Shalom in Ramat Beit Shemesh. Rav Yitzchok Lichtenstein — son of Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, rosh yeshivah in Har Etzion and grandson of Rav Yoshe Ber of Boston — is rosh yeshivah of Brooklyn’s Yeshiva Torah Vodaath, while his brother Rav Moshe stands at the helm of Yeshivat Har Etzion. Rav Tzvi Kaplan, a son-in-law of Rav Michel Feinstein, (son-in-law of the Brisker Rav), draws hundreds of the finest talmidim in America and Europe to his yeshivah in Yerushalayim. Rav Meir Twersky, a grandson of Rav Yoshe Ber of Boston, is a rosh yeshivah at Yeshiva University and rav of a shul in Riverdale, while Rav Meir Soloveichik, grandson of Rav Ahron, is rabbi of Shearith Israel in Manhattan, the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States.

So many paths leading back to the open Rambam on Rav Chaim’s table in Brisk…

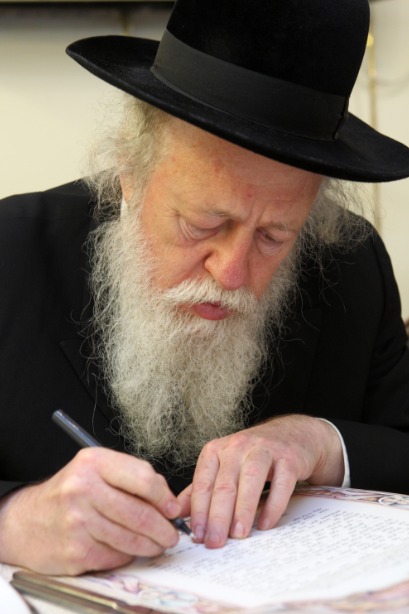

If Brisk were a chassidus, the headquarters would likely be located on Rechov Press, in Jerusalem, in the building erected over what was the Brisker Rav’s apartment. The room in which the Rav said his shiur remains intact, and it’s there that his grandson Rav Avraham Yehoshua, eldest son of his eldest son, says shiur as well.

If a picture of the Brisker Rav would suddenly come to life and walk the narrow road between Rechov Press and Zichron Moshe shtiblach, it would look like Rav Avraham Yehoshua: the sharp features, the piercing eyes, the square shoulders, the purposeful stride.

Rav Avraham Yehoshua was relatively young when his father passed away, just 33 years old. For a scion of Brisk, that loss was enough to turn the world upside down.

Di Tatte. In Brisk, those words are uttered with reverence, because only a father can instruct, can teach, can truly know — for only he knows what was. Practice and custom are decided only by viewing and absorbing what the Tatte did.

Until today, look as any child of Brisk walks down the Geula side streets: See the father surrounded by his sons, who walk straight as soldiers, speaking only when the father addresses them. The sons might be adults, accompanied by sons of their own — it makes no difference. There is a Tatte, and conversation starts and stops with him. He decides where to go, when to go, when to leave, and they move along with him, as if connected by invisible strings.

One of the American talmidim of 1960’s Brisk needed medical attention and went to an old Polish doctor. When the doctor learned that the patient studied at Brisk, he reacted with anger. “I have only felt intense dislike for three people in my life: Lenin, Stalin, and the rabbi of Brisk,” the old man said.

He explained that he’d once seen the Brisker Rav walking, accompanied by his sons. “And when I saw the fear they had of him, I reasoned that he must be a terrifying figure. I’m opposed to anyone who asserts authority through fear, and clearly that’s what the rabbi did.”

The bochur was quiet, knowing that there was no way he could make the old doctor understand the fear borne of genuine love, the awe created by exaltation, the trepidation resulting from the din, the words in the Torah that say, “Honor thy father and mother.”

When Rav Avraham Yehoshua was left without his own Tatte, he inherited a yeshivah. The yeshivah itself wasn’t so much an institution as a shiur. That group of his father’s senior talmidim continued to learn together, and until today, this shiur forms a small chaburah in the Achva Shul, just behind Zichron Moshe, supported by Rav Avraham Yehoshua. In the high-ceilinged shul with the creaky benches, they not only keep the Torah of Brisk alive, they also speak the language known only to insiders, talk of ibber-maasering (taking maaser off of produce for a second time), the achtel (the Brisker zeman for Motzaei Shabbos, one eighth of the day after shkiah), and the stencils (Torah from Rav Chaim and the Brisker Rav that wasn’t included in their seforim, but passed down by their talmidim).

In addition to the shiur in the Achva Shul, there was a group of younger talmidim to whom Rav Berel had given shiur in his home on Yosef ben Mattisyahu Street. Upon Rav Berel’s passing, Rav Avraham Yehoshua started to deliver that shiur. But something shifted in the small orbit of the yeshivah. Rav Avraham Yehoshua took the helm in 1983 and within a few short years, masses of American yeshivah bochurim were suddenly choosing to come learn in Yerushalayim — and many of them wanted to come to his yeshivah.

They wanted the mesorah, access to the zealously guarded “Torah shebe’al peh” of Brisk handed down from his zeide. (Even today, in 2019, when governments are toppled and relationships destroyed by leaked audio and video, where the safest rooms on earth have been exposed as vulnerable, you will have a hard time obtaining audio of a leaked shiur from Rav Avraham Yehoshua.)

They wanted to hear him, for he is a gifted maggid shiur, capable of articulating complex ideas in a clear fashion, taking lomdus, as one talmid expressed it, “and making you realize that it isn’t outside you, but inside you.”

Even after moving to the new building on Rechov Press, there was still no space. His father had a few minyanim in his shiur, and his zeide had less, but Rav Avraham Yehoshua’s yeshivah kept expanding.

A Closed Zeman

The term is enough to send spirits plummeting, leaving hundreds of American bochurim — and the roshei yeshivah advocating for them — trying to come up with a Plan B. It means that Rav Avraham Yehoshua has decided not to accept any new bochurim in his yeshivah for the coming zeman. What to do?

Over the years, some of the more aggressive fathers started to fly to Eretz Yisrael simply to petition the rosh yeshivah to find room for their sons. In doing so, they encountered another of Rav Avraham Yehoshua’s unique features: He abhors flattery and doesn’t extend extra courtesies to the wealthy. In Brisk, they learned, offering money was the surest way to buy rejection.

One innovative father found a way to penetrate the wall, using not money, but wit. He walked up the well-trodden steps of Gesher Hachaim 14, Kenissah Daled, and when Rav Avraham Yehoshua opened the door, the visitor stood there for an extra moment, a prayerful expression on his face.

“I feel like this one of the holiest sites in the city, a makom tefillah,” he told the rosh yeshivah.

“Farvoss?” asked Rav Avraham Yehoshua.

“So many fathers have stood here davening over the years, so many pure Yiddishe tears were shed right here by parents wanting the best for their children… how can it not be heilig?”

Rav Avraham Yehoshua smiled, appreciating the quip, and accepted the young man.

For this too is currency, a clever remark able to open doors.

In Brisk, there is no dormitory, but rather, the bochurim are given chalukah, a monthly stipend meant to cover their own needs. (It doesn’t come close, but it’s a nice opportunity for talmidim to speak with the rosh yeshivah alone once a month.)

In Brisk, there is also no formal mussar seder, as Rav Chaim was opposed to learning mussar. In all the main yeshivos, under Rav Meir and yibadel l’chayim tovim Rav Dovid and Rav Avraham Yehoshua, the mussar is included in the weekly Chumash shiur, at which hashkafah and direction is shared along with the lomdus.

Once, near the end of the Chumash shiur, Rav Avraham Yehoshua started to recount a maiseh, a story. He is a brilliant storyteller, and the talmidim were enraptured. Then he realized the time, and decided to say one more vort instead, leaving the bochurim frustrated.

“In Medrash shteit,” he began, “The Medrash says…”

A quick-witted European talmid spoke up. “Lo hamedrash ha’ikar, ela hamaiseh,” he burst out, using an axiom of Chazal in a clever twist.

There was silence for a moment, and then the rosh yeshivah laughed, his face alive with pleasure as he went back and finished the story.

The paradox of Rav Avraham Yehoshua is that while America is a frequent target of his Chumash shiur — he disdains the extravagance, the lack of depth, the double standard — he might be among the influential figures in the American Torah world, for most of the continent’s younger roshei yeshivah are his talmidim, and he is fully up-to-date on the realities and inner workings of their lives. He has a way of using words to their maximum effect, and one line in a Chumash shiur is likely to reverberate across the Torah world.

Brisk, to most people, still means that yeshivah, the one led by the oldest son of the oldest son of the oldest son of the Brisker Rav: Within it, a current oldest son, Rav Yankele Soloveitchik, says a popular shiur, the Brisker Rav’s Torah — the voice, the inflection, the coughs and “nu-nus” and “gezogt hut ehr gezogt” — still echoing off the walls that heard the Rav’s voice at a different time.

On a gray, humid summer morning, I drive to the Young Israel of Queens Valley, just off Main Street in Kew Gardens Hills.

The rav, Rabbi Shmuel Marcus, maggid shiur at Beis Medrash L’Talmud/Touro’s Lander College for Men, welcomes me to his second-floor office. Thoughtful and intelligent, the young rabbi chooses his words carefully.

Raised in Toronto, his fondest childhood memories involve summertime trips to Chicago to visit his grandparents, Rav Ahron and Rebbetzin Ella Soloveichik. Rav Ahron was a son of Rav Moshe Soloveichik, rosh yeshivah in RIETS, and the grandson of Rav Chaim.

Hidden within Rabbi Marcus’s nostalgia and longing is fire.

Along with sweet reminiscences about the house and community, Rabbi Marcus is essentially telling the tale of the Shulchan Aruch come to life, as if an engaging rebbi tried taking halachos and teaching them storybook style.

He speaks of his grandfather’s determination to fight his way back to health after a stroke. For 18 years following the episode, Rav Soloveichik — partially paralyzed and wheelchair bound — stood at the helm of a yeshivah and kehillah. From 1986 and on, he also traveled to New York each week, saying shiur at Yeshiva University.

“I would pick him up at the airport and marvel at his single-mindedness, his determination to walk by himself, to push a bit harder. I remember him climbing the stairs in his Chicago home, gripping the railing and counting stairs, pushing his right foot, then his left foot.”

Learning to walk again had become the “din,” and thus, it was holy.

One morning, Rabbi Marcus tells me, his grandfather was learning in the yeshivah before Shacharis. This was during the 1960s, before Rav Ahron had moved to Chicago, and he was a maggid shiur at Yeshiva University. A boy, a student at the nearby elementary school, came into the beis medrash carrying his school bag and, seeing as he had some time before Shacharis, he wanted to go play ball. He innocently asked the older man to keep an eye on his bag while he was playing.

Rav Ahron gently asked whether the boy meant to appoint him a shomer chinam or a shomer sachar. The boy was perplexed, unfamiliar with the terms, so Rav Ahron offered a brief shiur on the different categories of watchmen — the four types of shomrim and the relevant halachos.

The conversation took a few minutes and the boy lost his chance to play.

The next morning, the same youngster came with his knapsack and deposited it near the swaying scholar. “Please be my shomer chinam,” he said, before heading off to play.

Rav Ahron Soloveitchik had taken on a new identity.

When he returned home to prepare himself for Shacharis, he did so carrying the knapsack gingerly on his shoulders, as if the soccer ball, sweatshirt and snacks inside were valuable merchandise — because he’d become a shomer!

The holy shomer of the Gemara, the halachos, the Rambam, the nosei keilim: He was fully engaged.

“My zeide saw the sugya in a flash,” Rabbi Marcus says. “Practical problems and day-to-day issues were viewed through his command of the Gemara, Rishonim, and poskim on the topic. He didn’t hesitate, as a rule, because he saw things clearly.”

The emes of Brisk, Rabbi Marcus points out, was an outgrowth of Torah mastery. To know what’s true, one has to know the Truth first.

In the basement of the shul building, I see a group of elderly people sitting together, their conversation a babble of Polish and Russian. I comment to one of the shul personnel that the shul reflects its Brisker affiliation in terms of culture too, the languages of the Brest-Litovsk of old heard right here, in a Young Israel basement.

The answer gives me pause. “Oh, it’s a weekly thing, they gather to play games and chat, they look forward to it all week.”

It’s this, the kindness, that is the legacy of Brisk.

But is kindness its own virtue? Is the chesed of Brisk not just a byproduct of the Torah?

It’s a question facing Reb Shimon Yosef Meller during these weeks, as he puts the finishing touches on the second volume of his biography of Rav Chaim, called Rabban Shel Kol Bnei Hagolah.

While the first volume, released two years ago, focused on Rav Chaim’s development in learning — the Brisker derech, his own influences, his emergence as a maggid shiur in Volozhin, and transmission of his approach — this new volume starts from when Rav Chaim became rav in Brisk.

As the author started to assemble his stories for the book, he realized that there was a preponderance of stories about chesed, hundreds of accounts describing how the young rav in Brisk gave his time, his energy, and his heart for others.

Rabbi Meller felt that he could fill a separate volume with these stories, but feared it might be wrong to create a special volume focusing on Rav Chaim’s chesed when the subject is known for creating new fronts in Torah, in understanding Torah, in toiling in Torah, in teaching Torah. Would someone reading only the second volume get the wrong idea?

Rabbi Meller posed the question to Rav Chaim Kanievsky, who looked the author in the eye and said, “You’re doing this for parnassah, you should release the book in a way that’s best for sales.”

Rav Dovid Soloveitchik thought differently. He felt that each and every story should be shared, even if it meant creating a separate book. “Ah shud yeder ma’aseh,” the rosh yeshivah said, a shame for every story that would not get printed.

Ultimately, Rabbi Meller’s new book incorporates the chapter on chesed within the context of the larger story, but it’s by far the longest chapter.

But to ensure that the reader understands what motivated Rav Chaim, what was the fuel that ignited — and ignites — the house of Brisk, until this day, Rabbi Meller made sure to include a story in the second volume that leaves no room for error.

At one of the founding meetings of Agudas Yisrael, the rav of Brisk was asked to speak. He’d been worried about the idea of this organization, and had issued several conditions before agreeing to participate in the conference. Founding members Moreinu Yaakov Rosenheim and Rav Shlomo Zalman Breuer (son-in-law of Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch) offered opening remarks, and then all eyes turned to Rav Chaim.

There was a moment of perfect silence, in which Rav Chaim could be heard whispering, “der Rambam iz gerecht,” clearly in another dimension. Then he started to address the gathered rabbanim.

He told a story, as they will so often do in Brisk, to make a point. After his parents moved to the city of Slutzk, his mother went to shop in the marketplace. She noticed that the vegetables in the stall were packaged in an interesting way, little groups of different sizes wrapped together, with apparently no thought given to weight or quality. Some packets had two large vegetables, while others had four small ones.

She asked the storeowner how much a little packet of carrots cost. With great difficulty, he told her that the cost was drei ruble, three rubles. Then she took one of the oddly packaged bags of potatoes and asked their price, and again, the proprietor struggled and said that the cost was drei ruble.

The onions were similarly drei ruble, as was every single little packet on the shelf.

She wondered about the pricing system in the strange little store and asked a fellow shopper to explain it.

“Oh, of course,” the second woman replied, “the owner of this store cannot speak more than a few words, and even those are hard for him. The only number he can say is ‘drei,’ so he packages all his produce in ways that will have each one sell for the very same price, drei ruble.”

Rav Chaim completed the story and looked around at his fellow rabbanim.

“The storeowner only knew one number, drei, so everything in his store reflected that. I only know of one reality: Torah, Torah, and again Torah. That’s why the world was created and that’s why we’re alive and that is the only actual metzius. Anything in the world that is good for the Torah is also Torah, and anything that works against it doesn’t exist. There cannot be an organization called Agudah that has its own identity and goal, for there is only Torah.

“Now, if the organization is just a means of helping the Torah, then it too will exist — but that’s all there is. Nothing else.”

Rabbi Meller understood that this story provided direction for his dilemma.

Rav Chaim’s chesed, his activism, his tefillah, his middos, his leadership — they all revolved around his essence.

Long ago, on a gray late-winter afternoon, we asked Asher Soloveitchik a question….

And through time, through space, floats a tale of Brisk, a story from long ago as relevant in its implications now as it was then, words from a man of courage and kindness and holiness, so many threads wrapped around a single pole, a pillar that still stands firm.

Torah.

And so it endures.

How it endures!

Many Branches, One Root

The descendants of Rav Chaim Volozhiner — prime talmid of the Vilna Gaon and father of the modern-day yeshivah — refer to their family as Beis HaRav.

Seeds of the famed Brisker analytical method of learning can be found in the works of the Beis HaLevi, Rav Yosef Dov HaLevi Soloveitchik, the rav in Brisk. But it would be his son, Rav Chaim — born in 1853 — who would develop and sharpen the technique and use it in his shiurim.

After his marriage to a granddaughter of Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, rosh yeshivah of Volozhin, Rav Chaim joined the faculty of the legendary yeshivah and started delivering the formal shiurim that would illuminate the sky over the wider yeshivah world.

His sefer, Chidushei Rabbeinu Chaim HaLevi, based on the Rambam, changed the way people approach a sugya. Among his prime talmidim were Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, Rav Shimon Shkop, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, Rav Elchonon Wasserman, and his own sons, Rav Yisroel Gershon, Rav Yitzchok Zev, and Rav Moshe.

After Rav Chaim passed away in 1918, he was succeeded as rav in Brisk by Rav Yitzchok Zev, who was known by three additional names: the acronym “the Gri’z,” Reb Velvel, and also simply as the Brisker Rav. The Gri’z established a shiur in his home that drew bochurim from the great yeshivos. Many would eventually lead the next generation as roshei yeshivah. Rav Moshe served as rav in Raseyn, and then Khistavichi, before emigrating to America and being appointed rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon. Rav Yisroel Gershon lost his life in World War II, but his son, Rav Moshe, would emerge as a central figure in postwar Swiss Jewry, and much later, would be among the first gedolei Torah to rebuild yeshivos in Russia after the fall of Communism.

The Brisker Rav and most of his children escaped war-torn Europe and ascended to Eretz Yisrael in 1940, but his wife and remaining three children never made it out of the Brisk ghetto, where they met the same sad fate as most of European Jewry.

After the passing of the Brisker Rav, his eldest son, Rav Yosef Dov (Berel) assumed the leadership of the Brisk Yeshivah in Geula, and with his passing in 1981, he was succeeded by his eldest son, Rav Avraham Yehoshua, who leads the yeshivah today with great distinction.

The rav’s other sons, Rav Meshulam Dovid and Rav Meir, established yeshivos of their own, both of which are flourishing. After Rav Meir’s passing, his sons assumed leadership of the yeshivah.

After the passing of Rav Moshe in 1941, his son Rav Yosef Dov (also known as Rav Yoshe Ber) of Boston succeeded him as rosh yeshivah at RIETS and emerged as a dominant figure in postwar American Jewish life. Rav Moshe’s son Rav Ahron established Yeshivas Brisk of Chicago.

Many of the Soloveitchik grandchildren and great-grandchildren lead yeshivos of their own; in each, the distinctive Brisker approach is celebrated.

“This Is Your Triumph”

The great men of Brisk didn’t trust outsiders to protect their legacy of authenticity. The smoothest of talkers and most eloquent activists would find themselves unable to penetrate the wall formed by Brisker wariness. People would come to Reb Velvel’s house on Rechov Press and pitch ideas or suggestions: The Brisker Rav would sit there, expressionless, well aware that virtually any word could be used as a haskamah.

Nu, he might say, but nothing more.

His sons and grandsons are no different, the caution as hereditary as the aristocratic nose and piercing eyes.

Yet, Rabbi Shimon Yosef Meller earned the most precious commodity of all — trust. He is able to walk in to their homes and not just speak, but also hear.

It’s because he comes bearing a commodity that they treasure — the stories, the history, the details, that form so much of Torah shebe’al peh of Brisk. As a researcher, an interviewer, and a writer, he’s made it his mission to follow every lead related to Brisk, to turn over every stone possibly concealing a story, minhag, or comment made by their father or grandfather.

The stories of Brisk are part of the canon, used to answer questions in Chumash shiur, to explain a position, to solve a chinuch issue.

In a shiur on the mitzvah of sippur yetzias Mitzrayim, Rav Boruch Mordechai Ezrachi spoke about what it means to “relive” a story.

“When the Brisker Rav would tell a story involving the train from Bialystok to Kovno, he would tell you how many kilometers the route was, he would describe the scenery, the old wooden bridge. Why? Because,” concluded Rav Boruch Mordechai, “in Brisk, they don’t share stories that are history. If they tell the maiseh, it’s because there are nafka minos, real-world implications. The Brisker Rav was on that train when he told the story, because if the story was relevant, then it was alive and he was there.”

Rabbi Meller started his venture by authoring a series of seforim of Brisker Torah called Shai L’Torah, and then ventured even deeper into the world of Brisker lore, authoring a compendium of Uvdos V’Hanhagos (Facts and Customs) MiBeis Brisk. After breaking new ground with a four-volume biography of the Brisker Rav, he felt ready to go another generation back in time, and present his Rabban Shel Kol Bnei Hagolah — a full-length, definitive biography of Rav Chaim, published one hundred years after his passing. The first volume was well-received, and now he’s on the cusp on releasing the second.

Despite the fact that he’s been engaged in this sugya for close to two decades, he keeps finding fresh insights and streams of information. Six months ago, as the manuscript of Rav Chaim was completed, another door opened for Rabbi Meller.

One day he received a phone call from Rav Chaim Rabinowitz, the Chabad shaliach to Brest, Belarus (Brisk). The municipality had erected a sports stadium over the old Jewish cemetery many years ago, but now there was a friendly mayor and a chance to save what was left. The hope was that the remainder of the Jewish cemetery, including the gravesite of the Beis HaLevi, could be salvaged. Would Rabbi Meller want to join the effort?

Rabbi Meller booked a flight to Belarus, but first, he went to speak with Rav Dovid Soloveitchik, asking the rosh yeshivah if he remembered where the kever of the Beis HaLevi was located.

Seventy-six years after leaving Brisk for the last time, the rosh yeshivah looked up and offered precise instructions, as if he had been at the kever of his great-grandfather a week earlier.

“There are two entrances to the cemetery in Brisk,” he said, “one from the train station and one from the other side. Go in from the other side. You will see big ballates, huge stone tiles, and walk 15 steps into the beis hakevaros. Near the taharah shtibel is where the elter-zaide is buried.”

Once in Brest, Rabbi Meller followed the rosh yeshivah’s precise instructions, and as he approached the site, he saw the remains of what had clearly been the small structure, the taharah shtibel.

Just as Rav Dovid, who’d last been there as an 18-year-old, had said.

Just meters from the massive stadium, giants rest — not just the Bais HaLevi, but other rabbanim of Brisk as well: Maharam Padua, Rav Aryeh Leib Katzenelenbogen, the Imrei Moshe. There were the kevarim of Rav Chaim’s wife, Rebbetzin Lifsha, and even two of Rav Dovid’s siblings — the oldest daughter of the Brisker Rav, who’d passed away at 14, and another daughter who’d lost her life as an infant.

Rabbi Meller stood there in silent reflection, contemplating the Bais HaLevi, what he’d planted, what he’s created, and pledged to do whatever he could to honor the site.

He thought about the last day of the Bais HaLevi’s life, remembering a story he’d heard from Rav Dovid. There was a Jew in Brisk, a Kohein, who would attend to the Bais HaLevi and as a 90-year old man, he’d shared the story with Rav Dovid.

One Shabbos, this Kohein and his friend passed by to say gut Shabbos to the Rav. The Bais HaLevi looked at the friend and said, “Tomorrow you will be by me.”

The Kohein was deeply hurt. This was the first time the Rav was asking for one without the other. What errand did the Rav have in mind for his friend, in which he could not take part?

That night, the Bais HaLevi was niftar, and the next day was the levayah. The Kohein could not participate, of course, while his friend was there, “by the Bais HaLevi.”

The story isn’t about the mofsim, the prophetic vision of the Bais HaLevi, but about precision in speech, about how the Torah of this man endures.

Rabbi Meller understood that the brief flash of friendliness on the part of the local government was an opportunity to be seized, and he and Rabbi Rabinowitz headed directly to City Hall to formally “claim” the rest of the cemetery.

The official who received them and signed on the contract accepted their good wishes and thank you, and then offered a few words of his own. “The fact that you succeeded in building a new world in Israel that looks just like the one that was destroyed in Brisk before the war… that is your triumph!” he said.

One-hundred-and-twenty-seven years after the Bais HaLevi’s passing, the land was claimed, a sign erected, plans for a matzeivah drafted.

Rabbi Meller walked through the streets of the town, standing on the banks of the Mukhavets River and remembering Rav Dovid’s recollection of a summertime Erev Shabbos.

On Friday, Erev Shabbos Ki Savo, Rav Dovid related, he and his friends — the lions of Mir, who’d come to learn under his father, including Rav Leib Gurwitz, Rav Simcha Scheps, Rav Ephraim Mordechai Ginzberg, Rav Leib Malin, and Rav Michel Feinstein — had gone to the river to wash up before Shabbos.

Then the sky darkened and a strange noise filled the air. The bochurim looked up to see airplanes overhead — German planes, there to intimidate and, if necessary, overpower.

The young men fled. Rav Dovid himself hurried to one of his secret hideouts, a small shul called Chevra Levaya Beis Medrash, where he sat and recited the whole Tehillim, weeping throughout.

“Such a Tehillim-zoggen, with such dveikus and emotion, I have never experienced again,” Rav Dovid told Rabbi Meller.

Two weeks later, Germany occupied the town, and Rav Dovid left, never to return.

And six months ago, looking at the clear blue waters, gentle waves that promised serenity yet had seen such upheaval, Rabbi Meller had a thought.

The official at city hall had spoken with admiration of the fact that what had once been in Brisk, still thrived in Jerusalem.

“You don’t even know the half of it,” Rabbi Meller said aloud, speaking to no one and to everyone. “You have no idea how deep it goes.”

In Brisk, many questions are resolved by drawing a distinction between the gavra and cheftza, the individual and the action, as it affects an object.

The gavra that the town had known — the personas of its giants the Bais HaLevi, Rav Chaim, the Brisker Rav — is no more. But others have come, offering that same Torah, reading from yellowed notebooks and applying that thinking to new ideas as they remain faithful to the source.

In every beis medrash, wherever a Jew sits at a shtender, a gemara and a Rambam opened nearby, the cheftza of Brisk roars, a call for clarity and depth and truth.

The gavra, the cheftza, the Torah — they are all one, and they live.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 781)

Oops! We could not locate your form.