Breaking the Sound Barrier

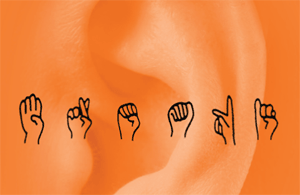

| December 14, 2011 “When I was growing up it was very rare to put a child with hearing loss in a mainstream class. I felt like I was the only deaf person in the world” recalls Rebbetzin Libbi Kakon who was raised in Williamsburg and Flatbush.

“When I was growing up it was very rare to put a child with hearing loss in a mainstream class. I felt like I was the only deaf person in the world” recalls Rebbetzin Libbi Kakon who was raised in Williamsburg and Flatbush.

Instead of using sign language Rebbetzin Kakon was taught from a young age how to lip-read and speak. Despite her hearing limitations she is now able to use a phone provided that the person on the other end of the line enunciates every word clearly.

Although Rebbetzin Kakon was always aware that she was different she was completely integrated into mainstream frum society. She only discovered later that most hard-of-hearing Jews aren’t so fortunate: “Over the years especially after I got married I found out through my husband (who is also hearing impaired) that there’s a whole deaf Jewish community out there that’s removed from the frum community. It’s devastating.”

Even when deaf people are active members of a shul they can still feel like outsiders. “I think my parents saw themselves more as part of the larger Jewish deaf community than as part of the local Orthodox community. They never really had close friends in the frum community since the communication barrier prevented them from forming deep relationships” says Ephraim K. the son of two deaf parents who grew up in the New York area. For social activities and support his parents always turned to their deaf friends. “The Jewish deaf community is very close-knit. They show up to every simchah and every event.”

This lack of integration is something that Yael Zelinger sees a lot in her line of work. As coordinator for the Baltimore-based Jewish Advocates for Deaf Education (JADE) Yael notes that many deaf Jews go outside the Jewish world into the greater deaf community for social interaction. “In shul they’ll maybe eke out a ‘Hi how are you?’ from fellow members. They feel very isolated ” she says.

Deafness by its very nature is isolating. But when that sense of separation is felt around fellow Jews it can lead to a separation from Yiddishkeit itself. “There’s always a danger of kids going off the derech but there’s a higher risk when a kid is dealing with the additional challenge of hearing loss ” says Rebbetzin Kakon.

Since the deaf Jewish population is a small minority there’s been little effort over the years to integrate them into our community. Indeed until recently there was very little opportunity for a deaf child to receive a Jewish education. This and a general lack of emotional support has led to an unknown but significant percentage of frum children leaving Yiddishkeit asserts Rebbetzin Kakon.

For those who stay committed there’s still a dearth of programs that cater to the hearing impaired. Consequently if a deaf person cannot access shiurim or join community events she ends up viewing religion as a bunch of restrictions — without the inspiration or depth. Going to shul can also be a meaningless experience for deaf people. If they can’t hear the davening all they’re left with is empty motions: stand sit and bow.

Beyond the religious world there are a lot of Jews in the secular deaf community who have never been exposed to Yiddishkeit. This group sadly is often skipped over by mainstream kiruv organizations.

“It’s much harder to be mekarev a hard-of-hearing Jew because even if you’re successful in bringing him back where are you bringing him back to? There’s no easy way to mainstream him into the hearing frum community” says Rebbetzin Kakon.

This may in part explain why the intermarriage rate among deaf Jews is very high. “They’re much more limited in their choices” says Batya Jacob program director for Our Way the Orthodox Union’s program for the deaf and hard of hearing. “And when they’re choosing a spouse they tend to worry about their communication requirements before Jewish requirements.”

At the heart of this issue is a sense of self-identity: Does an individual identify more as a deaf person — or as a Jew? This is an especially loaded question in the deaf world where being hard-of-hearing is not viewed as a disability but rather as a unique and positive characteristic.

To read the rest of this story please buy this issue of Mishpacha or sign up for a weekly subscription.

Oops! We could not locate your form.