Borderline Change

One year later, converging circles of heart and hope

Photos: Aviad Partush, Yitzchak Yirmiyahu, AP Images

A year after the day of infamy that capped months of zero-sum struggle over Israel’s soul, a road trip through the devastated kibbutzim of the Gaza border reveals that there’s a unique, epochal moment for a fresh start — a new dialogue about faith and fate, what it means to be an Israeli and a Jew.

T

he hum of drones and drumbeat of gunfire is the only music you’ll hear around the Gaza border nowadays — but dissonance there’s aplenty. A year after the attack that shook the world, jarring discordance is everywhere. It’s in the sounds of birds twittering over depopulated kibbutzim. It’s in the verdant foliage next to the blackened homes. It’s there in the tractor tilling the rich soil where the killers sowed death.

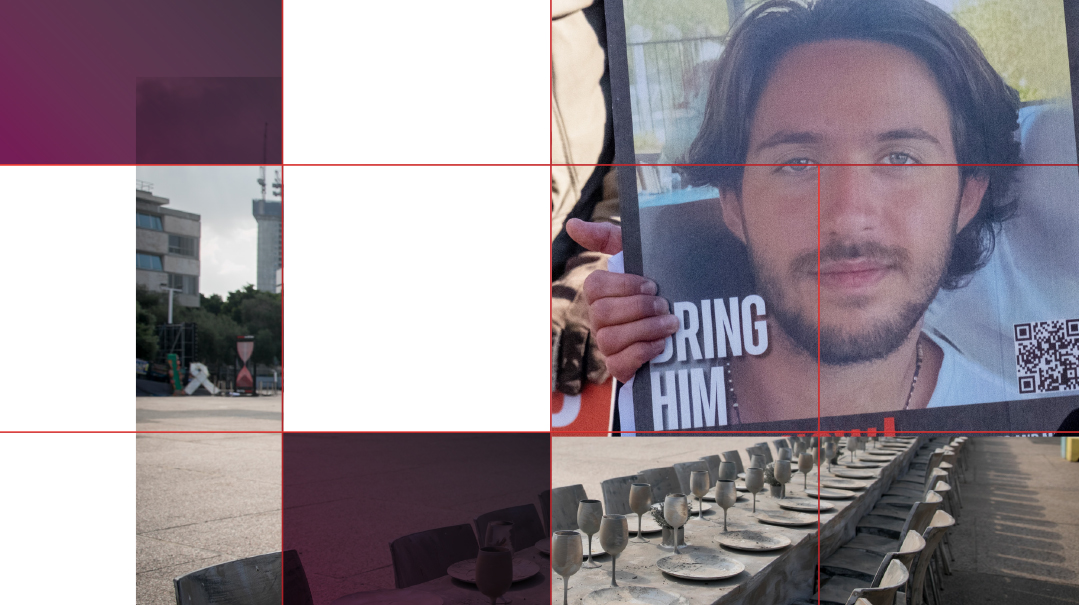

If there’s anywhere in the Gaza borderlands that dissonance reigns, though, it’s on Route 232, along which lie the graveyards that are Kibbutz Be’eri and Re’im. Ignore for a minute the hostage release placards that grow thickly by the wayside, and the road could be any main artery in rural Israel — complete with too few lanes and farm vehicles manned by Thai workers. But drive along the highway, and it’s all too easy to imagine the terrorists who spilled exultantly onto this axis that parallels the Gaza border.

That dissonance hits me one morning at the beginning of Elul, driving along the 232 on a mission to answer a question that has burned inside me since the Hamas attacks a year ago.

My copilot on this quest is Rabbi Shlomo Raanan, founder of the Ayelet Hashachar outreach organization and the man whose pioneering work building shuls in the kibbutzim across the country has made him familiar with nearly all the communities that dot the region. Over 25 years of painstaking effort to bring Jewish life to the many left-wing communities on the country’s borders, he’s developed a rare perspective on the hard, secular core of Israeli society.

In the apocalyptic aftermath of Simchas Torah, while secular soldiers donned tzitzis, hilltop youth hugged Tel Aviv techies, and chareidim fed the IDF massing on the Gaza border, anything seemed possible. So a few weeks after October 7, I picked up the phone to Rabbi Raanan with a question. “Are we on the cusp of a great change in Israeli society, a historic convergence of left and right, secular and religious, a new dawn for Jewish identity — possibly even a revivalist wave of teshuvah?”

His answer was prescient, recognizing the scale of what had happened, but cautioning against reading anything into the atmosphere of unity. “We’ve just undergone an earthquake,” he replied, “and it’s too early to see where the pieces will settle.”

Over the course of the ensuing year, Rabbi Raanan and I maintained an intermittent discussion — part hashkafah, part realism, part hope — about what was unfolding. It was a year in which the fleeting unity gave way once more to the old left-right and secular-religious rancor, where the fate of the hostages became politicized, and where chareidim once more became the lepers of Israeli society. By the year’s end, the impression from the media is that the seismic shocks of October 7 have left nothing but the same zero-sum struggle over Israel’s soul. But is that true?

Almost a year on, we’re heading to October 7’s Ground Zero to understand not only what went on that day, but to answer the same question that we’ve wrestled with for the past 12 months. Over the course of 12 stops and 20 hours of interviews, we talk with people from the left and the right, with foresters and politicians, farmers and engineers, people lining up for pizza, and others talking in their workshops late at night. To each and every one we ask the same identical question — one whose answer will mark the Jewish future.

“Did Israel’s day of infamy really change nothing at all?”

Amid the devastated kibbutzim, in conversation with the residents trickling back after a year’s exile, we hear strange stories of deliverance that some acknowledge as miracles and others insist on calling blind chance. We meet some people clinging to old stereotypes, and others whose deeply held beliefs have been shaken to the core. Alongside those firmly in denial, we find many people prepared to think afresh about Jewish identity.

Down by Route 232, under the sunshine interrupted by palls of smoke and velvety skies lit by occasional flashes, post-October 7 Israel comes into focus.

Step away from the headlines that proclaim that nothing has changed; talk to the people and it’s clear that change is indeed afoot.

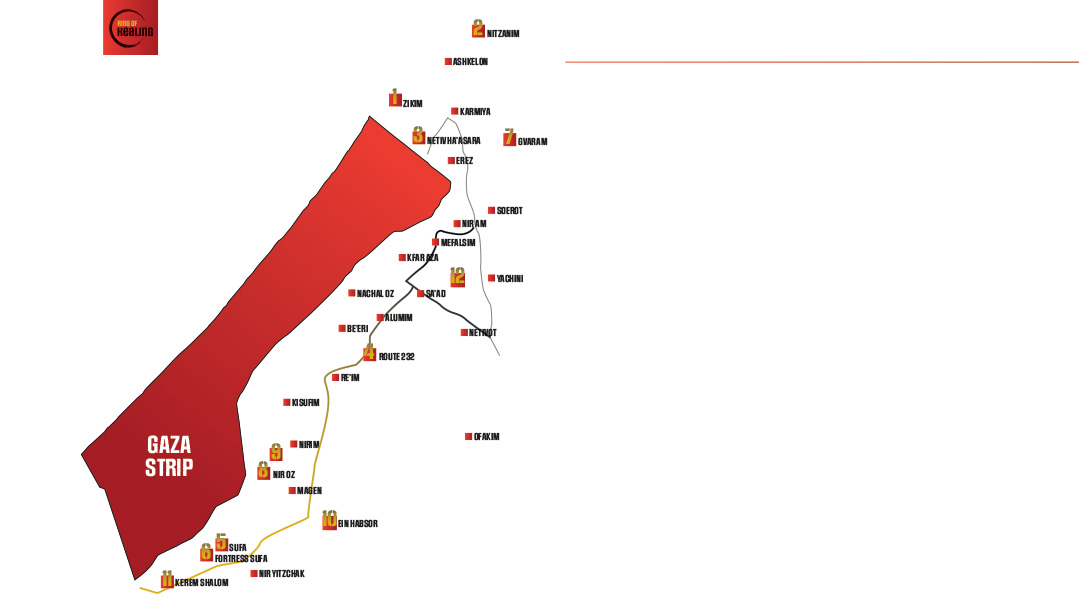

1: Kibbutz Zikim — Over the Beach

“This tiny shul saved us ”

The young socialist pioneers who founded Kibbutz Zikim south of Ashkelon in 1949 obviously had an eye for prime real estate. It’s an idyll. Azure waves and sandy beaches within hailing distance of the kibbutz houses — here at least, Karl Marx’s Workers Paradise lived up to its name.

Until last Simchas Torah, that is. On that fateful morning, Israel’s southernmost beach became the scene of a full-blown invasion. Security camera footage shows motorized dinghies speeding across the horizon, from Gaza to Israel. They’re packed with heavily armed Hamas frogmen, who’d trained for years for just this mission: to assault over the beach, destroy the army base adjacent, and then invade the kibbutz just a few hundred meters inland.

Israeli gunboats engage some of the force, firing at the dinghies and circling around individual frogmen in the water, as sailors lob grenades and fire heavy machine guns. But some of the terrorists — known in Arabic as “Nukhba,” or “elite” — evade the navy and make it ashore. They massacre 19 people camped out overnight on the beach, and then make their way to the army base.

That’s where the struggle for Kibbutz Zikim begins. From their homes a few hundred meters away, the kibbutznikim see everything. Nine terrorists get to the kibbutz fence, where four are killed by the defense squad, and five flee.

Beyond those bare statistics lies a story of survival — and as some locals see it, a miracle connected to a shul.

Yaacov Ohayon, a stocky man in his 50s, is a former policeman, current lawyer, and resident of Zikim’s “extension” — a modern area of spacious villas that lies between the original austere kibbutz and the sea.

A member of the kibbutz’s local defense squad, he was woken by the sirens and the volleys of missiles screaming overhead, and scrambled on his weapons and rushed to join the defense team.

A few minutes later, they were alerted that a Hamas force was at the kibbutz perimeter, directly behind Yaacov’s house. “We took positions behind these concrete blocks and saw a pickup truck full of Hamas fighters on the patrol road on the other side of the perimeter fence,” he recalls. “We opened fire straight away, emptying clip after clip.”

The terrorists came heavily armed; equipped with machine guns, rocket propelled grenades and even drones. It was clear, at least in retrospect, that they knew their way around the place. “Just two weeks before the attack, I saw one of the Arabs who was employed in construction here photographing my house with his phone. I thought he was taking a selfie, but now I know — it was all part of a mapping operation.”

It’s something that you hear everywhere in the region; residents remembering their own examples of the widespread intelligence gathering that was clearly part of Hamas’s master plan.

In one of the million acts of Providence that were everywhere on that grim day, Zikim’s local defense squad received unexpected backup in the shape of a squad of IDF Maglan special forces troops. Why were they there? A local resident who’s an officer in Maglan had punished five of his subordinates for driving in an army jeep without seat belts. Their punishment: detention on the adjacent army base for the Simchas Torah weekend.

Bolstered by the extra firepower, the defenders of Zikim managed to drive off the attackers who retreated to the nearby road commanding the approach to the army base. The terrorists were taking up positions when the Maglan squad infiltrated behind some sand dunes and killed them.

Best Defense

That storyline was widely reported in the media as the Battle for Zikim. But standing on the patrol road between his house and where the Hamas killers tried to enter, Yaacov Ohayon points out something that others have missed.

“The Nukhbas were outside the fence for a few minutes before we arrived,” he says. “It would have taken just a pair of wire cutters or a small explosive device like they used everywhere else to break in here, and then the results would have been the dreadful slaughter that we saw elsewhere. What were they waiting for — why didn’t they enter?”

For answer, Yaacov shows us to the parking space in front of his house, a few meters away from the spot where the terrorists tried to enter. Parked there is a little caravan containing what has to be one of the world’s smallest shuls.

It’s Yaacov’s pride and joy. As well as serving on the defense squad, he’s the gabbai of this midget shul. “Look inside here,” the gabbai says, turning on the air-conditioning. “We have everything here — an Aron Hakodesh, bimah, seats, siddurim.” It’s indeed a miniature wonder: five dinky mahogany pews with upholstered seats, a little wall-mounted Aron Hakodesh, and a movable amud.

The story of this place is the tale of the baby steps that some in the region are taking towards Jewish observance. With a Sephardic background, Yaacov is one of a cohort of more tradition-minded people who’ve moved to the old secular kibbutzim of the region.

Yaacov connected with Rabbi Raanan a number of years ago, when the latter held a hachnassas sefer Torah in a neighboring kibbutz. That meeting led the shul builder to set the ball rolling on a shul in Zikim.

When Ohayon applied to the kibbutz leadership for a permit, they refused. That wasn’t, perhaps, surprising: like many kibbutzim in the area, Zikim was founded after the War of Independence drew Israel’s then-Gaza border with Egypt. Of the various sub-ideologies encompassed by the kibbutz movement, the Hashomer Hatzair (“Young Guard”) movement that founded Zikim was the furthest left, a byword for secularism.

The no from the kibbutz leadership led Rabbi Raanan and Yaacov to pursue an unusual option: a shul small enough to fit into a parking space that would require no permit whatsoever.

Parked in front of Yaacov’s villa on the very edge of the kibbutz, it acts as the first beachhead of Torah life in this very secular place. Last Simchas Torah morning, it played a part in a very different type of beachhead, when Hamas attacked.

That’s why Yaacov Ohayon points Heavenward as he speaks about the rescue of Kibbutz Zikim. “I only have one explanation. Look where this happened: next to the shul. We were saved because of this shul.”

2: Lost Youth — Nitzan Regional School

“We’re a country living in fear”

I

sabel Sharon, a neighbor of Yaacov’s who serves as principal of a secular regional elementary school, had a very different experience. At 6:30 a.m., when the shooting started, she thought that it was another one of the occasional infiltrations that were a hazard of life in the region long before October 7.

“I sat on the grass outside my house watching the missiles. I felt okay — I was sure that the army would deal with things and that there was nothing to worry about,” she says.

Our interview takes place in the sprawling elementary school that she runs in Kibbutz Nitzanim, which lies halfway between Ashdod and Ashkelon. The most immediately noticeable thing about the place is its generous grounds. In a country in which space is at a premium, this is unusual — more American than Israeli. The reason is the location. Here at the borderlands of Israel, where few want to settle given the proximity to bandit country, there’s space. As we walk into the secular school, two chareidi visitors plus a videographer, we make an unusual sight, and the kids gather round. “Will we be on the news?” “Interview me! Interview me!” They jostle around us in their still-innocent way.

That impression of innocence owes more to their youth than any reality. These kids have survived a war, and some have lost their homes, neighbors and even family members.

As the principal of a school which serves many different communities across the region, Isabel has seen the sharp end of the trauma that the children have undergone. In her experience, it’s the parents who show most signs of being affected. The school operates a no-phones policy, which until October 7 wasn’t a problem. But in the last year, she’s had to deal with constant pressure from parents worried about not being able to reach their children at all times. “We’re a country living in fear,” she says. “I’ve personally become fragile. I was always strong, not a person who cries. Now I find myself easily doing that.”

In her cheerful office, complete with a large, colorful zebra and huge mural of a nearby vineyard, there’s evidence of Isabel Sharon’s burgeoning interest in Judaism. Alongside various works on education, there’s a large set of volumes on Jewish thought from a secular perspective, and next to that — a set of Zohar. It’s evidence of an intellectual journey that’s not unusual in Israel.

Isabel grew up in old-time Beit Shemesh, a heavily immigrant and Sephardic place populated with more than a hint of tradition. But she wasn’t by any means religious: marriage took her to a secular kibbutz, where she and her husband raised three daughters who have remained in the area, two in Sderot and one down the road in Kibbutz Mefalsim. One of her daughters became chareidi, a process that enriched her own spiritual growth and urged her to support the existence of Rabbi Raanan’s tiny shul. “My son-in-law won’t come to us for Shabbat if there’s no shul,” she explains.

Isabel finds herself in an unusual position, straddling the different worlds of growing tradition and avowed secularism in the Gaza border area. She’s able to inject little doses of tradition in the secular curriculum of the school because she’s clearly not an outsider bent on brainwashing the children.

That’s what Rabbi Raanan taps into by offering a gift as our meeting ends. Conjurer-style, he draws out of his jacket a new shofar and presents it to the principal. ‘This is for your office, and to show the children,” he says. “I’ll send a very straightforward video tutorial for how to blow which you can show the pupils.”

On that note of tradition, I ask Isabel Sharon, did October 7 move the needle at all in the direction of a stronger Jewish identity?

“It’s hard to measure these things, but I think that among the young people in Zikim there’s more openness to Jewish identity over the last year,” she says. “Our Beit Knesset had Selichot for the first time this year, and I see that among the 14 and 15-year-olds, they’ve started to come to shiurim by a rabbi who comes in from Ashkelon.”

3: Blind Fate — Netiv Ha’asara

“I’ve left politics behind ”

When news of the Hamas attack broke in London late last Shemini Atzeres, with bizarre reports of an invasion and hundreds kidnapped, I immediately thought of Netiv Ha’asara. To me, this village on the Gaza Strip’s northern border embodied the mortal peril of life on the front lines.

On a visit a few years ago, a local had shown me the remote-controlled gun emplacement atop the border wall — high-tech gadgetry that was infamously neutralized by drone-dropped grenades as the terrorists mockingly swept over the border.

Looming menacingly over the wall was a Hamas watchtower, a mere 30 meters from the first line of houses. Flying Hamas flags, it sported a large poster in Arabic and Hebrew with a clear declaration of intent: “Yamit — Netiv Ha’asara — out of Palestine soon,” it threatened, referring to the previous home of many of the local residents in the Sinai town of Yamit, which was dismantled by the Begin government when Israel withdrew from the area in 1979. “The destruction of the occupiers is approaching,” the sign warned.

Manned by plainclothes Hamas men carrying binoculars, the lookout post was an unmissable sign of the terror group’s warlike intentions. Locals used it as a barometer of the state of the conflict. “When we see the guard up there, we know it’s okay,” explained my guide. “It’s when the guard disappears that we worry, because it indicates that Hamas are up to something.”

Unless you actually saw it with your own eyes, it was impossible to fathom. The Israeli security establishment was so confident in their assessments that Hamas was deterred, that it was content to expose locals to living with terrorists literally peering into the kibbutzniks’ kitchen windows.

But for anyone living by the fence, it was obvious that Hamas weren’t about to sing kumbaya. Next to the kibbutz I saw a low-rise that acted as a lookout point. From the top, a regular “thump, thump” was audible — the sound of mortars firing inside the Gaza Strip.

“They’re always practicing,” the guide told me.

The blindness and hubris that reigned across the senior echelons of the IDF who were convinced that Hamas was more intent on governing Gaza than undertaking any military adventures was exposed to the world on October 7. And for the Israelis who relied on the IDF for their most basic safety, their failure has led to a disintegration of trust in the army as an institution.

“When the Red Alerts started and we heard the volleys of missiles, we felt safe,” says Nurit Avraham, one of the trickle of residents who’ve returned to the village after months in hotels and temporary homes. “We always trusted the army — not anymore.”

It’s a refrain that you hear well beyond the Gaza border. “Tzahal” draws fervent support when it means the rank and file. But in terms of the institution embodied by its senior officer echelon, the military’s reputation was left in tatters by the collapse of October 7.

That’s the reason that figures like Moshe Dotan — a middle-aged security officer patrolling the streets of Netiv Ha’asara — have become so important. Immediately after the Hamas invasion, more than 600 new kitot konenut — local defense teams — were established across the country as it became clear that the model of central defense had disastrously failed.

Sitting in their beautiful, newly built villa in Netiv Ha’asara, Nurit and her husband Dudu — a senior police detective — recount their story of escape.

“When the sirens went off, we got a message from my nephew Bar, who was in the Yamam counter-terror unit, that we should stay inside and close the shutters because there’d been an incursion,” Nurit recalls. “But part of Hamas’s plan to gain control of the area was to shut off the electricity. Suddenly, we realized that the shutters on our smart home made us vulnerable because without power we couldn’t operate them.”

Their three boys were down in the basement shelter, but the Avrahams were reassured by the messages from their nephew — who was killed later that day battling the marauders — that the situation was under control. So they remained above ground, working the phones and monitoring the village’s chat groups, which began to fill with reports of terrorists inside the moshav.

“Suddenly at 2:30 p.m. we looked out of the kitchen window and saw men in combat uniforms. They ran past our house without looking our way, over the construction site opposite and disappeared.”

United We Stand

What the couple had witnessed was part of the Hamas assault force that had managed to cross the fence. The attack began with the very Hamas lookout post that had menaced the residents for so long. Terrorists on top fired at the high-tech sensors and cameras astride the wall, effectively blinding the army to anything happening in the village.

Other terrorists used hang gliders to sail over the wall, and then began their murderous spree inside the moshav, butchering 21 residents and wounding many others.

Without electricity, the Avrahams sat in silence inside their bomb shelter, and waited in vain for the army to come. The trauma of that day is scored on their children’s minds.

“Now that we’re back in the moshav, my boys refuse to leave home on their own. They wake up at night with nightmares.”

Nurit herself has had another reaction to the attacks: she’s no longer interested in politics. Unlike the vast majority of the locals — both in Netiv Ha’asara and the surrounding region — who are left-wing, before October 7 both Nurit and husband Dudu were staunch supporters of the current government.

“I’m not afraid of saying what I think, so while my neighbors hung up anti-Bibi posters and went to demonstrate in Tel Aviv against the judicial reform last year, I hung up huge signs outside the house to support Netanyahu,” she says.

That’s all changed now. Nurit Avraham says that it’s time to move past the politics of left and right that brought disaster on the country. In the days after Simchas Torah, that feeling was universal. Many on both left and right recognized that things had gone too far. Mass demonstrations, reservists threatening not to serve, a culture war around mechitzos and a feeling of irreparable acrimony had fed into a sense that Israel was falling apart. To its enemies, the country looked like easy prey. On October 8, people were determined to abandon the tension and find strength in unity.

A year on, though, the rancor is back, and many are fearful that Israeli society will reach the same dangerous impasse as before. But talk to people like Nurit Avraham, and you get a sense that October 7 has indeed wrought a change — that they’re not prepared to descend into the same madness.

“They attacked because we were divided, so I can’t go back to the old politics,” she says.

4: Broad Front — Route 232

“ A geography of horror ”

ON

the drive south from Netiv Ha’asara along the length of the Gaza Strip, I understand two things about the geography of the Hamas assault. Firstly, how far inland the storm troopers got. The wave of motorcycle and truck-born killers were stopped at the Yad Mordechai junction, minutes from Ashkelon. Had it not been for Heavenly intervention in the guise of a few courageous soldiers who battled to repel the terrorists, Hamas could have rolled over Ashkelon like they did Sderot.

The 60-kilometer journey southward teaches something else: this was no mere raid. It was an invasion across a broad front. Initial reports talked of 2000 invaders, but it’s now known that 6000 Nukhba terrorists came. For the sake of comparison, that’s the equivalent of two US Army infantry brigades.

October 7 turned the once-commonplace Route 232 into a geography of horror. Be’eri, Nir Oz, Re’im — the names along this road are etched in blood on the pages of Jewish history. Over the last year, Rabbi Shlomo Raanan has traveled this route hundreds of times. It never fails to overwhelm him. “To think that over these very roads, just a year ago, the greatest slaughter of Jews since the Holocaust took place is hard to grasp,” he says as we pass the Nova festival ground.

Although Rabbi Raanan’s Ayelet Hashachar organization is active in secular cities across the country, the seeds of his career were sown 50 years ago, in this very area. He’s a talmid of Rav Yissochor Meir ztz”l, the legendary founder of Yeshivat Hanegev in Netivot, who created a Torah renaissance in Israel’s south, opening satellite yeshivahs in Ofakim and Sderot. After the Yom Kippur War, the Hamburg-born rosh yeshivah began to send bochurim to the kibbutzim of the Negev for Yom Kippur — a bold move, given the anti-religious hostility of many of the residents.

These were places where the concept of the chalutz as the New Jew reigned supreme, as expressed in a famous poem by Shaul Tchernichovsky, called “They Say There’s a Land.” The poem describes an imaginary meeting between a Zionist chalutz and Rabi Akiva, in which the pioneer asks: “Where are the holy ones, where is the Maccabee?” To which the sage replies “All of Israel are holy, and you are the Maccabee.”

Rav Yissochor Meir taught his talmidim that all Jews, however distant-looking, are deep-down open to connection. “He felt that part of the reason for the disconnect of secular people from Torah was because religious people didn’t initiate contact,” Rabbi Raanan remembers. “ ‘How can it be that a whole kehillah won’t daven on Yom Kippur?’ he would ask us.”

That early lesson in responsibility took Shlomo Raanan to the kibbutzim of the Negev, inaugurating his decades-long involvement with the region. Over the years he’s seen a softening of the founders’ militant atheism. “The makeup of the kibbutzim has undoubtedly changed in the last decades,” he says. “Many of the founders actually came from religious homes but developed an antipathy to religion. They were actively and consciously ‘anti.’ But the third and fourth generation is something else.”

The loosening of the secular stranglehold is evident in the creation of Zikim’s micro-shul, and in the small right-wing presence in Netiv Ha’asara. It’s part of a process of disenchantment with the old socialist pioneering ideas that began in the 1970s. And what’s happening in the kibbutzim of the region is a microcosm of the overall shifts in the country’s makeup. Israel is a tale of two countries, going in two opposite directions simultaneously. Like much of the Western world, its public space is growing more socially liberal. But there’s a parallel shift, just as marked: much of the country outside secular centers like Tel Aviv is becoming more religiously traditional.

The two processes began a half-century ago. The post-socialist Israeli left began aping the rising progressivism of Europe and America, and in tandem, the shock of the Yom Kippur War added fuel to the fire of the baal teshuvah movement. Fifty years after those processes began, is another surprise attack speeding up that transformation?

5: Miracles and Courage — Kibbutz Sufa

“Why were we saved?”

ON the anecdotal evidence of one riveting conversation, the answer is yes. It’s midafternoon, and we’re well behind schedule when we make it to Sufa, a kibbutz opposite Rafiach on the southern tip of the Gaza Strip. Given its proximity to the last active battlefront in Gaza, the kibbutz is a closed military zone and a virtual ghost town. Of its prewar population of about 230, only a few residents are back.

In one house, two kibbutznikim, Erez Dinar and Muli Cohen, sit and debate the only possible topic for people like them: what happened on October 7. Located just a few hundred meters from Gaza, Sufa came under massive attack on that dreadful day. When the army finally reestablished control of the area, some 300 bodies of Hamas terrorists were found in the orchard that flanks the kibbutz. More made it inside, where they killed three residents as the defenders fought back. Why they didn’t succeed in the mass slaughter that they perpetrated elsewhere is a topic that Erez and Muli have debated for a while.

“Why were we saved, why did we not have a slaughter like in Be’eri, Nir Oz?” muses Cohen as the pair sip water. “I don’t have an answer to that.”

Dinar, a baseball-cap wearing kibbutznik who since losing his son in a car crash six years ago has undertaken a religious journey, replies: “I have an answer, but you won’t accept it. For us secular people, it’s difficult to think beyond the material. But there is an explanation, which is that we were saved because that’s what G-d wanted.”

“I respect everything, and accept everything, and I don’t know what secular means,” responds Muli Cohen. “People say they don’t believe, but those are just words.”

It’s a fascinating response from someone so outwardly secular, revealing of the eye-opening nature of what he witnessed. Erez Dinar presses home the lesson.

“Listen to me, Muli,” he says. “You know what happened to Michal and Moshe? Their front door wasn’t even locked. She sat in her living room, frozen with fear, while the terrorists fired through the window and banged on the front door. The strange thing was that they didn’t even try to turn the handle of the door — they just hit the door.

“You know what else was strange? That these terrorists who’d trained for years how to get into the kibbutz spent an hour and a half searching for the entrance when it was just a few hundred meters beyond them. Or the fact that they dropped bags of weapons in front of one of the houses and then couldn’t find it again. What happened to them?”

As the pair of old neighbors sit there toying with their plastic cups of water, Erez Dinar shares his rock-solid conviction.

“There’s only one explanation — that HaKadosh Baruch Hu blinded them.”

Dogged by Failure

Erez and Orit Dinar’s own story of survival points the same way. Under the layer of dust that has built up over the last year, their house looks like a war zone. Books, kitchenware and clothes are piled everywhere, evidence of the hurry with which they fled. Where the living room window used to be, there’s a sheet of plywood. Small-diameter Kalashnikov bullets have punctured the bookshelves and shattered the flat-screen on the wall. At one point there’s a hole with a far larger diameter, where a whole volley was fired in perfect alignment, gouging out the deep score in the wall.

In this room on Simchas Torah morning, Erez — a retired policeman — witnessed one of many miracles that kept his family alive. A kibbutznik who cofounded Sufa’s shul with Rabbi Raanan, his involvement with the shul put him directly in the firing line.

“They knew exactly who they were looking for,” Erez says of the Hamas attackers. “They knew that I’m in charge of the shul. I used to give the Palestinian workers a drink, and when they broke into the kibbutz, they came looking for me.”

As everywhere in the Gaza area, life as they now know it began at 6:30 a.m. that morning. Erez was already awake, preparing to open the shul, when the rockets overhead told him that this was no regular Yom Tov morning. He stayed home, and a short while later the assault on his small, bungalow-style moshav house began.

Failing to gain easy entry, the Hamas killers began looking for the mamad — or bomb shelter room. But here something happened to slow the terrorists’ assault.

“They couldn’t find the mamad — it was blocked by our succah,” Erez points to the outside of his house. “That in itself is strange because all the houses in the moshav are identical, so it was a simple matter of comparison to find their way in. But having failed to find it, they went to the other side of the house to break in from there.”

Erez’s experience wasn’t the only case of the “succah that saved me” in the wider Gaza area, and he references a startlingly relevant passuk: “Ki yitzpeneini b’suco.”

It wasn’t the only inexplicable intervention that acted to delay the attack on the Dinar house. For the heavily armed Hamas assaulters, it should have been an easy break-in to the flimsy kibbutz house — yet it didn’t happen.

Out of nowhere, a dog bounded over and leaped at the stunned terrorists. It was no ordinary animal, but an attack dog recently retired from the army’s Oketz K9 unit and adopted by a resident on the other side of the kibbutz. No one knows how the dog got loose, or why it headed right across the kibbutz to the Dinar house, but it did its work.

“They had to shoot the dog,” says Erez. “See, it’s buried here outside my house. But that took more time, and in the meantime, the moshav’s defense team arrived.”

It’s only a couple minutes from his house until the shul that was Erez’s pride and joy, and we retrace the route that he would have taken had he left to shul that morning. Along the way, the emptiness of the kibbutz is oppressive. It’s the quietness of danger and things lurking.

Perhaps fittingly, the shul is a converted public bomb shelter. Its existence explains why in this very secular place — Erez Dinar calls it “atheist” — he’s convinced that what the kibbutz experienced was a miracle, and not, as some locals maintain, blind chance.

When the lights and air-conditioning go on in the subterranean shul, the dedication plaque is revealed: “Sha’agat Kfir” — the lion cub’s roar, it’s called, after the Dinar’s eldest, Kfir, who was killed in a car crash at 23 years old.

The loss of their eldest six years ago devastated the Dinars, and Erez decided to say Kaddish in his memory. He started to go to shul in the nearest place, a moshav called Pri Gan that lies to the south of Sufa.

On Shabbos, that meant a 12-kilometer walk each way, which Erez faithfully undertook whatever it cost him — scorching heat or torrential rain. Among kibbutznikim, many of whom see Jewish tradition as utterly foreign, Erez’s decision to say Kaddish stood out. But his openness to tradition was obviously latent.

“Before the crash, I had this superstitious kind of habit: before going on a car journey, I would say some words of prayer,” he says. “But when I drove on Shabbat I wouldn’t say it, because I felt it was hypocritical. How could I ask for help going on a journey that I wasn’t permitted to take?”

The strikingly confused yet honest reasoning showed the struggle at play in Erez Dinar’s soul. It took his son’s tragic death for that struggle to emerge to the forefront.

After months of walking back and forth every Shabbos, Erez decided to install a shul in his own moshav. The decision to commemorate his son by installing the village’s first shul met with a combination of official skepticism and general apathy. But his own personal example as homegrown spiritual leader won through. “You can’t bring a rabbi into a place like this, because he would be seen as imposing on us,” he says. “But I made my friends an offer — you come to my shul on Shabbat morning, and then afterward we’ll sit by the pool together.”

The inroads that Erez made in the secular kibbutz were evident after October 7, when the residents gathered to take stock of their escape in the Eilat hotel they’d been evacuated to. The gabbai advertised that they were going to say Hagomel and hundreds of people joined.

If the good burghers of Kibbutz Sufa act as a pulse-check, what do they tell us about the secular mindset post-October 7?

“There’s confusion,” Erez responds. “People understand that strange things happened to save them, and they’re scared to call it a miracle because of the implications for their lives. But there is an openness that wasn’t there before. People are willing to listen. The question is if we know how to speak to them in the right way.”

6: Sound of the Shofar — Fortress Sufa

“We headed home”

AS the sun dips towards the Mediterranean, we head over to a lookout point with a commanding view of the Sufa battlefield. Along the patrol road outside the kibbutz, army jeeps with tall communications wires honk their horns at us as they head to inspect the border. Their base is the Sufa strongpoint, a fortified outpost where a vicious battle raged on October 7. Across the road is the orchard where piles of Nukhba terrorists met their end, machine-gunned from the air by a pair of Apache helicopter gunships that appeared over the kibbutz as the defenders battled the odds. At the right angle where two lengths of chain fence meet is where the attackers vainly sought the entrance for so long, as Erez Dinar said.

Just a mile away, the lights of Rafiach wink cheerily, belying the evil of the people who live among them. Under the large town on the Gaza-Egypt border, Hamas archfiend Yahya Sinwar is known to be hiding, surrounded by his human shield of desperate Israeli hostages.

It’s clear even from our vantage point that the battle is still ongoing. Every so often there’s the buzz of an Israeli drone overhead; a few minutes later comes the telltale smoke of an Israeli airstrike.

As shkiah approaches, a makeshift minyan gathers. A few young soldiers from the nearby strongpoint pull up, and a member of the local defense team ambles over with his dog. There’s a special moment as Erez’s 13-year-old son Tomer puts on tallis and tefillin.

Tomer has his own story of survival involving this lookout point. “I was standing here at 4:30 a.m. the morning of October 7 with my friends,” he says. “After all-nighters, we often come out here to watch the sunrise, but this time one of my friends felt sick, so very uncharacteristically we headed home. If we’d been here when they attacked, we would have been shot.”

It’s a sobering thought for a young boy, but in today’s Israel, far from unique. Joining us in the minyan is Effie, an English-speaking soldier from a moshav near Beit Shemesh. The war has led him to rethink a lot about his life.

“I grew up religious, but left it behind because it felt like I was doing stuff on autopilot,” he says. “The war forced me to focus on my priorities in life, and today I’m on my way back. I think my generation is divided into two: those open to more Jewish tradition like me, and those who bury all thoughts about heavy stuff because it’s hard to engage with it.”

Mincha ends, and Rabbi Raanan takes another shofar out of the back of his car as a present for Effie, who has volunteered to be the baal tokeia in the Sufa strongpoint. The rabbi asks the assembled — some with scraps of cloth on their head in place of kippahs — to gather round.

“Somewhere under the buildings opposite are the hostages, and only Hashem has the power to release them,” he says. “May the shofar, which is a call for freedom, serve as an omen that they too will walk free.”

A murmur of “Amen” echoes from the motley minyan, a tekiah pierces the air, and the Gaza border is once more shrouded in bombed-out darkness.

7: Pipe Dreams — Kibbutz Gvaram

“We’re all just Arabs ”

A

few days later, I find myself once more on the road with Rabbi Raanan. The previous round ended near midnight with the kind of brain fog that accompanies most intensive reporting trips. There comes a stage where the adrenaline gives out, the brain turns to mush, and the stomach turns to food. The latter proved a problem because late at night in the mostly depopulated Gaza border area, there aren’t a whole lot of mehadrin food options.

So the patrons of Yossi’s pizza whom Rabbi Raanan kept asking our perennial question — “Has anything changed since October 7?” — did not receive the justice that they deserved. Barak, a right-wing forester disagreed on politics with the Tel Avivian army officer picking up a stack of pizza pies for her troops. But both agreed that it was back to the same old enmity. “I live where the anti-Bibi protests happen on Rechov Kaplan, and I can tell you that nothing has changed since the war began,” she said.

Perhaps it was the gloom of the late hour, but in Sdei Avraham — a moshav down the road from Sufa — a similar pessimism reigned. Dov Markovitch, a flower grower and member of the defense team, sat with his friend Reuven — originally from Argentina — and spoke of rebuilding over a cup of coffee. There were lots of smiles when Rabbi Raanan whisked a mezuzah out of his pocket to put up in Dov’s workshop, but a cloud hung over their conversations. “It feels like we live in multiple countries,” said Reuven of Israel’s fractured society.

But for Gili and Dana Tavor, who host the opening session of the new day, optimism was the dominant feeling as they went into the Shabbos of October 7.

Residents of Kibbutz Gvaram just north of the Gaza Strip, they had just returned from a holiday in the Sinai, where they’d been hosted by an interfaith couple. “She was Russian-Israeli, and he was a Muslim from Cairo,” says Dana. “We had a wonderful time, and I returned home thinking that if they could do it, maybe there was hope for us all. Maybe there’s hope for peace with the Muslim world.”

Like many in the region, Dana believed that her own efforts to befriend the Gazan workers — like donating coats for their children for winter — would bear fruit in terms of peace.

Against the background of her own family’s recent roots journey to Germany, Dana conveyed that optimism to a German TV crew who made a documentary of her story discussing her opinion of the ongoing anti-government demonstrations.

“On October 6, we’d done a wrap on the filming, where I told them that I believed things would be good in Israel, both internally and in terms of peace with the Palestinians.”

Early the next morning, that narrative was shattered forever in the wave of missile attacks that struck around the kibbutz. Located in an isolated area a few kilometers from the Hamas onslaught, Gvaram should have been easy pickings for the terrorist, but somehow the terrorists didn’t manage to penetrate the border fence. Rockets struck all around the kibbutz but didn’t make an impact inside either.

“Like every year, that Friday was celebrated as Children’s Day, when parents and children set up tents in the kibbutz center and camp overnight,” says Dana. “Had the terrorists broken into the kibbutz, or the rockets struck, we would have faced a slaughter like the Nova.”

Why indeed did that not happen? Dana herself is clearly pulled in two directions on whether the kibbutz’s survival owes itself to Providence or blind fate. She refers to “hashgachah” as playing a role, and then quickly adds “or mazal — whatever you call it.”

“Some people around here say that it was a repeat of what happened in 1948, when nearby kibbutzim were attacked but Kibbutz Gvaram escaped because of the remoteness,” she hedges.

Mugged by Reality

Dana is far less ambivalent when it comes to the utopian vision for peace she touted just a year ago. “I never thought I’d say this, but I can’t stand to talk about peace anymore. That’s all gone.”

It’s just six weeks since the family moved back from their yearlong exile. The house remains a museum to the pre-October 7 era, with the paper chains from a birthday party that took place a few days before the attack still hanging on the walls. 12-year-old Itamar is still getting used to going back to school in the area.

He sits down and agrees with his mother. “I don’t think that it’s possible to have peace with the Palestinians — they hate us too much,” he says. But joining the conversation as he blends a vegetable and protein shake, husband Gili — who works in high-tech — is of a different mind than his wife and son. “For sure we need to defend ourselves,” he says, “but that doesn’t change the fact that we can and need to make peace with our neighbors.”

As the discussion widens to the anti-Semitism that has set Jews apart on campuses and in workplaces all over the world, he doubles down on a secularist view of Jewish identity. “We’re just another, white-skinned type of Arab here in the Middle East,” he says. “We shouldn’t continue thinking of ourselves as so different.”

On the face of it, beliefs like these challenge the notion that anything has changed in terms of Jewish identity post-October 7. But as Gili heads off upstairs for a Zoom meeting, his wife has the last word: “He’s just saying the words he always said — but after the last year, he doesn’t really believe them anymore.”

8: Inquisition Pyres — Nir Oz

“An Eichah landcape”

Nothing prepares you for a visit to a place like Nir Oz. The hardest hit of all the Gaza-area kibbutzim, a quarter of its 400 residents were killed or taken hostage — a higher percentage than anywhere else. Here, Hamas were so successful in their bloodthirsty rampage that they cleaned the entire kibbutz out and then left before the rescuers came. When the army finally arrived, they found the smoking, despoiled corpse of a kibbutz.

Walking between the rows of its charred bungalows is hard to describe — like entering a death camp just a year after the Holocaust. The sheer savagery of the attackers is only too obvious. What did they have against the sweet old lady whose face — on a ubiquitous red and black hostage poster — is framed over her own doorway? What did they have against the family with the kiddie slide that still sits outside one torched house?

To walk around these people’s homes feels like an invasion of privacy. There are someone’s singed fridge magnets laid out carefully outside their front door as if they had been excavated from Pompeii. A cooler bag — strangely untouched — stands next to a rocking chair on someone’s porch, with a child’s booster seat mute witness that whole families were snatched. The molten remains of ovens — twisted in the fierce heat of the Inquisition-pyres — sit next to shards of pottery that now look like archaeological relics.

I walk around the utter stillness of this kibbutz with a feeling half-reverential — like someone in a beis olam — and half-pulsing anger. What manner of beasts could do this?

Strips of green grass and foliage run parallel with the rows of burnt bungalows — a juxtaposition of life and death that only serves to emphasize the destruction. In a place like this, one feels, nothing ought to grow.

Here in Nir Oz, the mind grasps for comparisons, some historical framework to make sense of its enormity. Parallels from the Jewish past are inevitable. Amid the stillness of disaster, it’s clear that this is another Eichah landscape.

9: Way Home — Nirlat Factory

S

itting amid the wreckage of the Nirlat paint factory in Nir Oz, Yelena Trufanov makes a strange contrast to the destruction around her. A Russian-born chemist who ran the plant’s quality control lab, she’s now on paid leave after Hamas destroyed the whole facility. The industrial machinery is burnt, with some of the large storage tanks toppled sideways. “I don’t have a lab,” she says matter-of-factly.

How this woman is cheerful defies belief. Captured along with her son Alex and his fiancée Sapir Cohen on October 7, she and her future daughter-in-law were held in captivity separately and then both released in November’s prisoner deal. Her son is still in captivity and she has no idea whether he’s alive.

Perhaps her equanimity comes from her own experience. Her group of captives were treated relatively humanely by the captors, not tortured and abused like others.

But perhaps it stems from her own faith — an entirely October 7 creature. Raised in Soviet Russia, she immigrated to Israel in 1999 and ended up in the left-wing kibbutz, with virtually no exposure to religion. But sitting in captivity, she concluded that there was only one logical explanation for the utter collapse of the IDF: Divine intervention.

“The captors said to us, ‘Where was your army? We never expected to take more than a few soldiers.’ And what’s the answer? It was because G-d wanted this to happen,” Yelena says. “I can’t fathom any other possibility to explain a disaster of this scale.”

That diagnosis has led her to an unusual conclusion. “I’m not angry at Hamas,” she says of her former captors. “They’re just a tool in the Hands of Hashem. Because we had no unity, G-d struck us, and if we don’t find unity now, we’ll get another blow until we get the message.”

To hear Yelena Trufanov’s monologue is to encounter an Avraham Avinu revelation. She quite simply revolutionized her life based on her own thoughts. She now keeps Shabbos and kashrus, and is learning all that she can about a life of mitzvos.

Yelena’s account highlights something beyond one person’s amazing metamorphosis: her discovery of the empathy of the religious world.

“When I was released, I visited the Kosel and a group of chareidi girls approached me and said, ‘Are you Yelena? We prayed so much for you!’

“Until that happened,” says the former hostage, “I had no idea that chareidim cared about us.”

To hear those words is to hear confirmation of Rav Yissochor Meir’s exhortations to his students half-a-century ago. How many Yelena Trufanovs are waiting in the wings after October 7, waiting to discover that we really care?

10: Reviving the Spirit? — Ein Habesor

“A melting pot ”

Having focused on the man in the street, my pilgrimage around the Gaza border has been blessedly slogan-free. But my one encounter with a politician provides an eye-opening tour of the new ideological landscape that has emerged over the last year.

It’s late afternoon when we pull up in Ein Habesor, a moshav about halfway down the Gaza Strip, to speak to Michal Uziyahu, who’s tipped to take over the Eshkol Regional Council, the local authority that abuts Gaza.

She and her husband Amir, who’s busy walking two enthusiastically slobbery hounds when we arrive, are a model of coexistence within marriage. “My husband is a ‘schmutznik,’ ” she declares fondly, using a derogatory name for a member of the far-left Hashomer Hatzair movement. “He won’t even touch a gun, and I lean right.”

As ever, the conversation begins around October 7 itself and the family’s experience. They were fortunate that Ein Habesor emerged unscathed. In another of the myriad seeming-coincidences that decided the fate of each individual kibbutz, the dozens of terrorists who attacked Ein Habesor met a large, well-trained defense force because a spate of robberies in 2022 had led to the expansion of the smaller initial team. The defenders were able to stop the marauders at the kibbutz gate.

As the family sheltered in the basement, Michal told her young teens, “You need to snap out of the fear — this is the end of your childhood.”

It’s clear to her that the country has moved right, including many of those in the region who were once notable doves. “Before October 7, we didn’t see the sadism and cruelty that lay on the other side of the fence,” she says.

Uziyahu also had her own encounter with the top brass’s self-delusions about Hamas intention leading up to the attack. After Rosh Hashanah last year, with Hamas staging daily provocations at the border fence in what was in hindsight an attempt to distract the IDF, she shared her concerns with General Yossi Bachar, the deputy head of the Southern Command who lived in Kibbutz Be’eri. “He told me that the army wasn’t worried about Hamas because they had no motivation to attack.”

Beyond a trust gap, Michal Uziyahu sees other signs of a shift in mentality as a result of the war, in an abandonment of the soft mindset of recent years in which people came to kibbutzim less as pioneers ready to sacrifice than in search of living space. “Most kibbutznikim will return,” she says “and I believe that there’ll be a revival in the pioneering spirit that built these areas. I know of two groups of Hashomer Hatzair who are waiting to come back and resettle Nir Oz.”

Although there is talk in the government of repopulating the desolate northern and southern borders with various inducements, it’s not clear that in modern, consumerist Israel a revival of the pioneering spirit will be so easy.

But there’s one area where the politician is clear that fears for Israel’s future are overblown. Despite the return of political acrimony over the fate of the hostages, she notes that there were always yawning gaps between different populations in Israel. “Remember the Altalena, when Ben Gurion’s Haganah men shelled Begin’s arms ship in 1948?” she asks rhetorically. “We’ve been fighting for thousands of years, and it’s going to be okay.”

And the fighting itself has led to a bridging of the gaps between left and right, secular and religious, she says. “Those thousands of reservists who met and fought side by side from all walks of life — that created a melting pot effect in Israeli society. We don’t yet know how that will play out long term.”

11: Coexistence Lab — Kerem Shalom

“Peace is possible”

IF the whole of the Gaza border area feels like a military zone, with observation blimps overhead, army jeeps throwing up dust everywhere, and checkpoints at every moshav, Kerem Shalom takes the hypervigilance to a whole new level. Located on the tri-border of Israel, Egypt, and Gaza, this kibbutz feels like a forward operating base.

The residents trickling back share their space with various infantry and rescue units. Here a unit gets kitted up to patrol the Philadelphi Route — the strategic road that separates Gaza from Egypt — and there a column of armored vehicles lies swathed in camouflage sheets.

As if to emphasize the fact that this is a front line, wild dogs roam free. They’ve crossed over from Gaza and have been adopted by the soldiers.

I’m here to meet the head of the local defense squad, Eliyah Ben Shimol. It feels like a closing of circles — early in the war, I spoke to him at length by phone about his heroic part in the battle for Kerem Shalom, which earned him the enduring respect of the kibbutz’s mostly secular residents.

“You’re looking a lot better than when I saw you last over video call — minus the bulletproof vest,” I greet the religious security officer.

“Baruch Hashem,” he smiles in response. “We’ve smashed Hamas and they can hardly fire at us at all.”

His HQ speaks worlds about the militarization of the border region. The sprawling former kindergarten with its faded cartoon murals is now a fortress. Ceramic vests, rifles, ammunition boxes and radios abound where toddlers’ sippy cups and toys would have been kept.

Pointing at a map in his room, Ben Shimol talks us through the day-long battle in which a handful of defense volunteers held off dozens of terrorists. Two members of the team died fighting to save the lives of the vast majority of their fellow residents.

But we’re not here to talk about the past. I’ve come because of the unique viewpoint possessed by this particular ravshatz, as the security officers are called.

A few years ago, the kibbutz leaders were forced to face the reality that the younger generation was leaving for a better life away from the shadow of Gaza. They needed radical new solutions to bring in a new generation of residents who were idealistic enough to live on Israel’s borders. That led to the unthinkable: Kerem Shalom — once a byword for the furthest left of left-wingery — became the new home of a group of families from the National Religious world. The group needed a shul, and they naturally ended up on Rabbi Raanan’s doorstep.

It was a multiyear experiment in coexistence that had the new residents navigating flashpoint issues with strategic delicacy. The secular residents thought that the newcomers would move to close the kibbutz swimming pool on Shabbos. But the newcomers sufficed, instead, with asking for separate swimming hours during the week. “We knew that a power struggle would achieve nothing,” says Ben Shimol. “We had to develop a model where all sides — religious and secular — felt that they achieved their core needs, and weren’t threatened by the other.”

That model of understanding meant that the intense strife of the year of protests against the Netanyahu government largely passed the kibbutz by — despite the fierce ideological nature of the newcomers.

As we sit once again over a meal of Yossi’s ubiquitous, extra-cheesy Gaza border pizza ordered from the same mehadrin joint as a few days before, Eliyah Ben Shimol ticks off the list of changes that the country has undergone since October 7. There are the familiar: the left that has moved right, the breakdown in trust of the army and central authority.

But there’s also a perspective born of this genuine right-wing, religious effort to coexist with the left, and not just to defeat it in a power struggle. Ben Shimol is of the Michal Uziyahu school of thought; he feels that the fabric of Israeli society is stronger than suspected, and has been strengthened by shared trials.

“Do I fear for the future, as we split into left and right once again? No, I’m not scared. I’m confident. Because we all saw that unity that came to the fore right at the beginning of the war, in a time of intense fear. It proved that we can come together, that deep down we’re still one.”

12: Showing Up — Yellow Gas Station

“Build it and they’ll come”

I

t’s perhaps fitting that a two-day shul-hopping, battlefield-touring, hashkafah-trading listening tour fueled with bad caloric choices should end with more junk food, one last shul, and a searing insight from the Meshech Chochmah.

Velvety night has once more fallen over the Gaza border region, and somewhere along a dark road we stop at a branch of “Yellow,” a gas station chain. We sit down on a picnic table outside with an unusual young couple who want to build a shul in another kibbutz. He’s a third-generation kibbutznik who’s obviously somewhere at the beginning of a religious journey, and she’s the daughter of Ethiopian immigrants.

Over a cup of instant ramen, the man tells a by-now familiar story. “The old ideology is gone, and people are open to new ideas — even Judaism,” he says. “I think people will come to a shul if I build it.”

He’s a construction worker and literally wants to build the shul with his hands, and Rabbi Raanan talks them through some initial steps. “Don’t fight the kibbutz leadership — work with them, not against,” he urges.

Have I witnessed the first baby steps in establishing a new kibbutz shul? By the looks of it, it’s doubtful. This man doesn’t project the charisma, grit, or take-charge attitude of the Yaacov Ohayons or Erez Dinars of the world — local chiefs who can take people with them.

But like Rome, shuls aren’t built in a day; the long, sure road to spreading Torah in some of Israel’s most secular climes means one meeting after another, one contact then another. It’s a question of direction, not how long it takes to get there.

And having spent two long days among the people hardest hit, the direction of travel for Israel seems clear. Startling examples of teshuvah are vanishingly rare, but there are many whose journey back to their roots began on October 7.

The baby steps in Jewish identity that are evident all over this region, says Rabbi Raanan, are a harbinger of a deeper process at work. “When a person returns to his people, he’ll certainly return to his G-d,” the Meshech Chochmah says in Parshas Nitzavim. Building an identity that finds strength in Jewishness on the rubble of secular universalism is painful work, but in many conversations it’s clear that that process is underway. For a generation that experienced the hammer blows of the Hamas assault, Rav Meir Simcha of Dvinsk’s words ring truer than ever.

The barely perceptible shifts that are evident when you talk to people about how October 7 changed them echo the almost-prophetic words of Rav Yitzchak Hutner in 1977, who spoke of a “teshuvah-readiness” as a stage before the full return of the Jewish people. More than ever, we are living that concept.

Amid the crumbling of old certainties about Israeli military prowess, Palestinian peace, and the Jew’s place in a world rife with anti-Semitism, a historic opportunity is unfolding: a rare window of openness on all sides of the left-right, secular-religious chasm. It’s a unique, epochal moment for a fresh start — a new dialogue about faith and fate, what it means to be an Israeli and a Jew.

“People are prepared to listen,” concludes Rabbi Raanan, as the causeway of death, Route 232, fades into the darkness of the Gaza border. “The question is, will we show up to talk?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1033)

Oops! We could not locate your form.