Border Lines

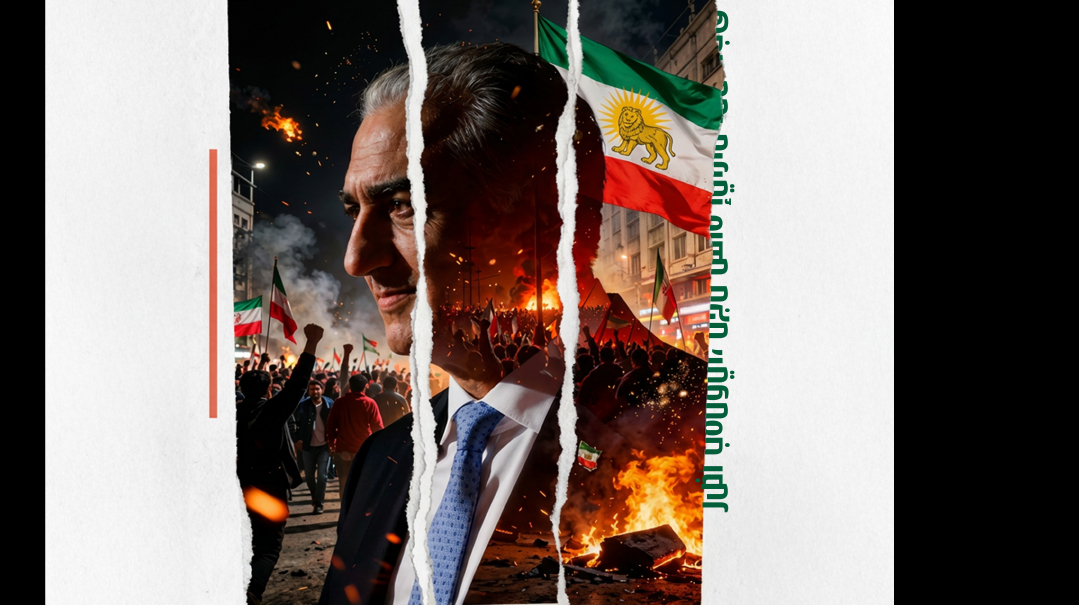

| July 22, 2025Will Israel’s defense of its loyal minority torpedo the White House plans for a new Middle East?

Photos: Flash90

The last thing Israel needs is to get bogged down in the Syrian quagmire, but what happens when over a thousand Israeli citizens — many of them experienced IDF combat soldiers — breach the border to protect their relatives being slaughtered by the new Syrian regime? Will the intervention on behalf of Israel’s loyal non-Jewish minority torpedo the White House’s big plans for a new Middle East?

Just minutes before midnight, the home of Sheikh Mowafaq Tarif, perched atop the Druze town of Julis in northern Israel, is bustling. In the spacious living room, middle-aged men pace with urgency, phones pressed to their ears, trading rapid updates.

It looks like a war room — because it is one.

Outside, two young men are exchanging and collecting names of the dead. The names keep coming in — from As-Suwayda, southern Syria. Nearly every family here has relatives there.

Just a week before my arrival, Bedouin militias — together with forces loyal to al-Julani’s so-called “Syrian Army” — stormed As-Suwayda, the capital of Syria’s Druze heartland. The result was swift and brutal: Hundreds were executed in the streets with unimaginable cruelty. Elderly men and sheikhs had their mustaches forcibly shaved in public as a form of humiliation. Homes were burned. What began as a local dispute —between a young Druze man and a group of Bedouin — rapidly escalated into a massacre that many residents say echoed the horrors of ISIS.

The cheers that rang out in December when Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad fell have now been replaced with desperate pleas for help. The Druze community in Syria had hoped the new regime would protect minorities. Instead, they found themselves under attack. Promises of inclusion were replaced by an attempt at forced Islamization.

Ahmed al-Sharaa, the new ruler who emerged from the ranks of Al-Qaeda’s jihadist networks, proved to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing. His pledges to protect minority rights vanished the moment the Druze refused to surrender their weapons and join his army. The response was calculated and cruel: a siege on the region, blocked access to food and medicine, and the deployment of forces alongside Bedouins in a vengeful campaign of terror.

The battles last week claimed the lives of hundreds of innocent civilians. Reports suggest over 300 were killed in the brutal clashes. The Druze — there are about half a million in the region — found themselves outnumbered, fighting for survival. Only Israel’s military intervention, including airstrikes in Damascus and southern Syria, secured a fragile ceasefire.

Julis is essentially the face of Israel’s newest — and most unexpected — battlefront, into which it has been sucked in without much choice. However, the reverberations of this latest conflict are likely to be far-reaching, both further afield in the region and all the way to the White House.

Sheikh Tarif, 71, the spiritual leader of Israel’s Druze community, has barely slept in a week. His living room has become a de facto crisis center, coordinating aid and updates from Syria. When I arrive, he is on the phone with officials in Washington while simultaneously receiving updates from As-Suwayda.

“We cannot stand by and watch our brothers be slaughtered,” he says, his voice shaking. “This isn’t just a connection of religion or ethnicity — it’s family.”

A Nation Divided, a People United

The Druze are one of the Middle East’s most unique communities. Their religion, which split from Ismaili Shi’a Islam in the 11th century, developed its own theology, traditions, and sacred texts, which are copied by hand and kept secret. Crucially, they are considered heretics by the various streams of Islam.

To make it easier to defend themselves, the Druze historically settled in mountainous regions: Lebanon’s Chouf mountains, the Galilee and Mount Hermon in Israel, and “Jabal al-Druze” in Syria’s south. This division was created as a result of waves of immigration and dispersal, but Druze communities remained closely connected —spiritually, culturally, and through family ties.

Over the years, the Druze split up over various countries, according to borders set by foreign powers. Today, there are about 150,000 Druze in Israel, 400,000 in Lebanon, and around 600,000 in Syria. Many families are still split across borders, but still maintain strong emotional ties with each other. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in the Golan Heights, where Druze families that grew up under Syrian rule until 1967 were divided after the war that year and still have relatives just across the fence.

The events of recent weeks have posed a moral and emotional dilemma for Israel’s Druze community. They are loyal Israeli citizens who serve in the army and participate fully in public life. But they are also watching their relatives being slaughtered on the other side of the border.

“How Could We Not Go?”

Outside Sheikh Tarif’s home, I meet Yousef — who insists I call him “Yossi,” as he was called in the army. He is 36, a father of four, and a former IDF combat soldier. Last weekend, he was among the hundreds who crossed into Syria to help his fellow Druze.

“You have to understand,” he says, “at that moment, we couldn’t see anything in front of us except our brothers.”

“Imagine on October 7, when people were being slaughtered in southern Israel, someone told you that you couldn’t go help. You hear the screams of children — you know they need you — and you’re told to stay back. Do you think a concrete barrier could stop you? No way. That’s what it felt like. We saw and heard our people being massacred, and it was October 7 all over again — for us. How could we not go?”

They gathered at the fence near Majdal Shams, at a spot known as “Shouting Hill,” where families separated by the 1967 war would once shout across the border to one another. “At first it was just talk in our groups about going in [to fight in Syria —K.B.], but we weren’t sure how to go about it. Then about 200 people gathered within a few minutes, spontaneously. By afternoon there were over a thousand of us, and eventually the soldiers couldn’t hold the line and they opened the gate.”

Once through, the crowd surged forward. “I was one of the first in. I was with my cousin and my son. We ran uphill toward Hadar. Locals came and picked us up, taking us into the village. Convoys followed, carrying hundreds inside.”

In Hadar’s main square, he describes a surreal scene. “Hundreds were there. Gunfire in celebration. Family members hugging after decades apart. I met relatives and we spoke, and then I went to my mother’s sister who lives there — I hadn’t seen her in over 30 years. It was the most emotional moment of my life. I wanted to continue to As-Suwayda, but my cousins insisted it was too dangerous. We sat and drank coffee, we chatted, hugged, and two hours later, they returned us to the border on motorcycles.”

At the fence, he says, the scene was even more moving. “Hundreds were there — both from Syria and Israel. Families from all over the Golan had come to see their loved ones. Brothers and sisters embracing for the first time, crying together. It was an unbelievable sight.”

We asked him to try calling his aunt, but she didn’t answer. Instead, we spoke to his cousin in Hadar. “We’re always in contact and we know what is going on there,” he says, in impressive Hebrew. “When they began to gather at the fence, there were some of our young people there on the other side who saw everything, and when they came across, they came to inform us right away.

“We hoped it would happen. We wanted it to happen in an organized fashion, and that the Israeli government should understand the need, but even this way — it was beautiful. Yousef and I had never sat together for coffee before. We knew each other, we were in touch — but always across the fence. It’s been dividing us since we were born. This was the first time we were truly together.”

“We Just Want to Live”

From there I continued to Majdal Shams. I’d been here months ago, the day Assad fell. Back then the streets had erupted in cheers and fireworks. Today, the atmosphere is somber and tense.

I walk across town toward the security fence separating Majdal Shams from the Syrian village of Hadar. As I approach, I spot a small group of young men talking casually with IDF soldiers. Just a few hours earlier, some of these young men had tried to cross the fence into Syria. Others had been drinking coffee in Hadar a few days ago.

One of them, Amir, 28, works for the local council. He points to a house across the fence. “See that? That’s my aunt’s home. She lives within shouting distance of us — but she can’t visit. She has four kids. Her youngest is three. My mother wants to see him, but she can’t.”

He pauses. “This week she called crying, saying they might have to flee Hadar. She’s terrified Julani’s forces will reach them next. But where can they go? Her entire life is there.”

“I know it wasn’t right, what we did — crossing the border,” he adds. “But look around. We can see their homes from ours. We hear their kids crying. We know who was killed. This isn’t some faraway country — it’s right there. If something were happening to your sister across the street, would you sit at home doing nothing?”

He connected me to his relative Hamed in As-Suwayda. During the call, we hear gunfire in the background.

“There’s still shooting sometimes,” he explains in Arabic as his cousin translates. “We don’t know if it’s intimidation or real fighting. We haven’t left our homes after dark in two weeks. The kids are terrified. Last week they [the security forces —K.B.] came and dragged people from their beds. My neighbor’s brother was taken and hasn’t come back. We don’t know where he is or what’s happened to him.”

“The massacre here was like ISIS,” he continues. “They came with Korans in hand, calling us heretics, saying they’d ‘return’ us to Islam. They shaved the mustaches of 80-year-old men — on the street, in public. Our situation is desperate. If Israel hadn’t intervened, we wouldn’t be alive today. And if Israel doesn’t keep helping us, they’ll come again. They said there’s a ceasefire, but they are still here and they won’t be quiet.

“They’ll finish us — and come for you next. We’re just a small speed bump on the road to Israel.”

When I ask how he sees the future, his voice softens. “We just want to live in peace. We don’t care about politics. We just want to raise our kids like human beings. But apparently, even that is too much to ask.”

The fragile ceasefire attained a few days ago is holding, but there is still sporadic gunfire. The Druze in As-Suwayda are under partial siege, and are running low on food and medications. The Bedouin tribes have largely retreated from the city, but some of them are still holding onto pockets of territory. Syrian government forces have remained outside the city, but they have erected roadblocks and are controlling all access routes.

The Druze community in As-Suwayda is trying to reorganize after the massacre. Dozens of families have left the city, fleeing to villages in the mountains. Others are barricaded into their homes, waiting to see what happens. The local leaders have tried to shore up their agreement with the government authorities, but some of the younger set are rejecting every compromise, and want to continue with the conflict.

Israel Drawn In

As the battles in Syria still rage, the Druze in Israel are tense. Many of them are still in Syria, some in Hadar, and others deeper in Syria. The IDF has tried to return them, but many of them refuse to leave their families. This situation has generated a harsh dilemma for the Israeli government, which on the one hand wants to defend its citizens, and on the other hand understands the deep emotional connection between the Druze and their brothers over the border.

Whatever happens, it is clear that the emotional map of the Druze community has experienced a paradigm shift. Borders that appeared impenetrable for decades turned out to be very fragile in the face of the pain of people who saw their families suffering. The Druze discovered that despite the political divide, they are still one nation, one community, one large family that cannot really be divided.

The question is what these feelings of brotherhood will cost Israel. The events of recent days present a new and unexpected image of Israel: drawn into deeper military involvement in Syria — driven not by strategic ambition, but by the deep emotional and familial ties of its Druze citizens to the victims just across the border.

Within a single week, Israel carried out dozens of airstrikes on Syrian targets, including direct hits on the Syrian defense ministry headquarters in Damascus and areas near the presidential palace. Military sources report that three additional IDF divisions are being readied for deployment to the Golan Heights — the largest military buildup in the area since the Yom Kippur War.

“We don’t want to get bogged down in the Syrian quagmire,” says a senior Israeli security official. “But when a thousand Israeli citizens breach the border and enter Syria — and many of them are experienced reserve combat soldiers — this is no longer a matter of choice, but of obligation. We could not stand idly by when we saw October 7 happening all over again within the community most loyal to us.”

The combination of an 83 percent IDF enlistment rate among Israeli Druze — the highest in the country — and their direct family ties to the Syrian victims compelled Israel to act. Nearly 2,000 Israeli Druze signed a petition stating their intent to join the fighting if attacks didn’t stop — including active reservists.

That reality forced Israel’s defense establishment to face a hard truth: The alternative to official intervention might be the unraveling of one of Israel’s strongest relationships with a non-Jewish minority.

In Jerusalem, a new security doctrine is taking shape: preserving the Druze community in southern Syria as a natural buffer zone — akin to Israel’s past alliance with the South Lebanon Army (SLA) until its withdrawal in 2000. But unlike the SLA, which Israel created and armed from scratch, the Druze of Syria are a 700,000-strong community with their own military tradition and existential motivation.

“They’re not the SLA,” says the official. “They have identity, structure, and they’re fighting for their homes — not for us.”

He notes that the Syrian Druze community has its own independent militias and weapons, and they have proven impressive fighting tactics despite being outnumbered by the government forces fighting against them.

The question remains: How far will Syrian Druze go in cooperating with Israel? For decades, they’ve imbibed anti-Israel propaganda. But that may be changing. A video recently showed Syrian Druze waving flags and cheering IDF vehicles passing nearby. One even flew an Israeli flag.

This poses a strategic dilemma. Supporting the Syrian Druze could create pressure to do the same for other minorities — like the Kurds in northern Syria, who face similar threats. But unlike the Druze, the Kurds are geographically distant and are more closely allied with the US than with Israel.

From Peace Talks to Missiles

Just a week ago, there was cautious optimism in Washington and Jerusalem. President Donald Trump had lifted sanctions on Syria, seen as a gesture toward normalization and the admittance of Al-Sharaa to the international community. Quiet back-channel talks were underway between Israel and Syria, led by senior figures like National Security Advisor Tzachi Hanegbi, Mossad director David Barnea, and Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar.

“There were a few weeks of real hope,” says a source close to the talks. “Al-Sharaa was showing openness, Trump wanted a deal, and Netanyahu saw a historic opportunity.”

But the events in As-Suwayda changed everything. Israeli strikes on Damascus, including the Ministry of Defense and near the presidential palace, triggered muted American concern. “We told them to stop and take a breath,” said one Trump administration official, “but they kept bombing.”

Now, normalization talks are frozen. US officials describe frustration with Netanyahu, with some close to Trump calling him “reckless.” The consequences could stretch beyond Syria — jeopardizing efforts to expand the Abraham Accords.

Israel’s intervention has also drawn criticism from Turkey and Saudi Arabia, both of which expressed concerns to Washington. The message: Israel is seen as disrupting broader US policy in the region.

At the same time, human rights groups and foreign governments are watching the new Syrian regime with alarm. The massacre of the Druze followed similar attacks on Alawites and Christians — raising fears that Al-Sharaa cannot control extremist factions within his ranks.

A Costly Commitment

For Israel, the strategic price of intervening on behalf of the Druze may be heavy. Not only have the chances of normalization with Syria been pushed away to the distant future, Israel may find itself committed to a long-term involvement in a region where the central government is weak and many militias compete for influence.

While Israel successfully defended the Druze in this round, the question is what happens next time — and what will be the price of a long-term entanglement for a community in the heart of hostile Syrian territory.

One thing is clear: This crisis has permanently redrawn the emotional map of the Druze people. Political borders may have separated them for decades — but in the face of mass killings, they have rediscovered what they always were: one people, one community, one extended family.

The question now is: What price will that rediscovery carry?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1071)

Oops! We could not locate your form.