Blasts of Tradition

| May 26, 2015

Today, in Yerushalayim and other Israeli cities, the air raid siren takes the place of the traditional six shofar blasts at candlelighting time. In the Tunisian island of Djerba though, the ancient tradition has been preserved. Residents say that the shofar was abolished in other communities due to fear of provoking the non-Jews, but because they live in what is essentially an all-Jewish enclave they’ve continued to maintain this practice since ancient times. On our trip to visit Djerba’s Jews just two months ago, we were looking forward to experiencing it firsthand.

But as Shabbos approached in the Jewish community of Djerba, we found that they had another ways to herald its arrival: The kehillah hires someone to circulate in the Jewish Chara Kabira neighborhood to encourage shop owners to lock up, in addition to the original custom of blowing the shofar.

The Djerban community is proud of its adherence to the ancient rituals, tracing its 2,000-year sojourn on the island to a group of families of Kohanim exiled after the destruction of the Second Beis HaMikdash. While most of the hundreds of thousands of Tunisian and North African Jews have moved to Israel, France, and other countries over the last half century, the Jews of Djerba — all 1,300 of them shomrei Torah umitzvos — have stubbornly held onto their island community, secure in the government’s promise of protection and in the zechus of their unwavering commitment to halachah. Here the boys learn in yeshivah seven days a week until they secure a trade and marry, and chillul Shabbos is unheard of. Today the community — which makes up over half of Tunisian Jewry — is actually on the upswing, as many of the young families have chosen to stay.

And when Shabbos comes in, so does a feeling of old-world tranquility. Rav Chaim Biton, the community rav and official shofar blower, has been ushering in the holy day for the last 50 years. He was a teenager when the previous blower moved away, and has been blowing every Friday since. We arrived at the Rav’s house well before candlelighting: One of us took up a position in the “town square” from where the blowing can be heard, and the other accompanied Rav Biton and his shofar up to the roof. With the serious demeanor of a man who knows his community depends on him, he took his shofar, ascended to the roof, took up his position at one of the highest points in the town, and after frequently looking at his watch, at ten minutes to candle lighting proceeded to blow the first series of tekios. Having given it his all and looking a bit winded, he paced the roof for the next ten minutes and — having regathered his strength — then again took up his position and, as has been done for many hundreds of years, blew the shofar to let his community know that it was once again time to usher in the holy Shabbos.

But we weren’t prepared for what happened next. We quickly stowed away our cameras and rushed off to shul. And sat and waited in a near-empty room. Finally a young man came in and explained to us that most of the shuls wait an hour after candlelighting before davening Kabbalas Shabbos. In the interim though, he gave us a tour of most of the shuls of the Jewish quarter. In one shul there were about 20 young boys chanting Shir Hashirim. We passed by the Jewish school and heard singing, but our guide smiled shyly and explained that he couldn’t go inside. Looking through the window, we saw why: teenage madrichot were leading young girls in the Friday night davening.

No Compromises

Rav Biton fits the Rambam’s description (Hilchos Talmud Torah 1:9) that “among the great sages of Israel were woodcutters and water drawers.” He doesn’t earn a community salary, but supports his family with his small shop that supplies materials and equipment to the silversmiths. He sits there for hours learning and writing his teshuvos until somebody comes in with a question. We squeezed into the cramped shop after someone came in with a sh’eilah and saw he had a pile of ten seforim on his desk, all on issues of mourning. He was toiling over a notebook which, he explained with a touch of pride, contained his responses to various halachic questions.

We learned that before 1948 and the aliyah of the vast majority of North African Jewry, they used a sort of cursive Hebrew script, called “ktav chatzi kulmus” or Solitreo. At a quick glance, it looks like a form of Rashi script, but when you try to read it you realize it’s not the same. Rav Biton told us that he wrote all of his original teshuvos in that script and now he was copying them over into standard Hebrew in order to have them printed.

His painstaking mission to preserve halachah’s essence seemed an apt entrée to the community he serves. Four years into the “Arab Spring,” and just after a major terrorist attack in a Tunis museum, the steadfast, religiously insular Jewish community is a rare island of serenity, as uncompromising on halachah as ever.

It’s the only Jewish community in an Arab country whose numbers have increased in the last few years. There are a whopping 13 active shuls, but with only one Jewish doctor and one engineer, the occupational distribution differs from most other Jewish communities. Here, 90 percent are engaged in silversmithing and jewelry making. Having spent all of the formative years studying nothing but Torah, most young men don’t continue to higher secular education.

While it’s common legend that the community was originally comprised exclusively of Kohanim, today there are plenty of Yisraelim among the population. What is missing are Leviim. There is not one on the entire island of Djerba, which made Ari G., a Levi, somewhat of a celebrity. And because they only duchen on Shabbos and unmarried Kohanim — the bulk of our Shabbos minyan — do not duchen, here we were on the famed island of Kohanim and we didn’t even get a brachah.

Our host, Uziel Haddad, told us that when he was ready to get married, he spotted a fine young woman and asked his father if he could arrange for him to marry her. Within this tight-knit 1,300-member strong community, all the different families know each other, and the marriage to Rivkah was swiftly arranged. That was 20 years ago and things haven’t changed significantly. Both in school and on the street, Djerban boys and girls are completely separate. Once a shidduch is agreed upon, the young couple does not speak. The engagement period can be up to a year, during which the chassan (literally) builds a dwelling place for them to live in and establishes his livelihood. If one of the grandparents passes away, the wedding could be put off for yet another year until the parent finishes their aveilus, something that happened to two couples we met.

It’s in the Details

The Djerban Jewish community is an active, vibrant, religious community in every sense. There are several shochtim and mohelim, schools, a yeshivah, at least four kosher eateries, a commercial matzah bakery, and even their own pareve ice cream manufacturer. But it’s their attentiveness to the details of halachah that make the deepest impression. We met a man and two of his young kids leading a sheep toward their house on Erev Shabbos, and asked him, “Is the sheep for Pesach?” Aware of the halachah (see Shulchan Aruch Orach Chayim 469) that one should not designate an animal for “Pesach” lest one mistakenly think it is for the Korban Pesach, he responded pointedly, “It is for the Chag HaPesach.”

On Shabbos, Djerba’s Jews — like many others — maintain the ancient practice of mezigas hakos, adding a little water to the glass of wine. But for the Djerbans, it’s not just a ritual but an honor, as the father chooses one of his children to approach him and pour some water into the becher.

When we wanted to take home some matzah from the local factory, they almost jumped down our throats to make sure that we took nothing out of the plant before challah was separated.

Modesty is a critical component of the Djerban lifestyle, and many families have a kosher mikveh in their own houses, so no one has to be seen using the facility. In the courtyard of the community mikveh is their source of aravos. They looked like healthy and vibrant willows; which makes sense considering that every time they switch the mikveh water, the old water gets pumped out to water the aravah plants.

We’d heard about the Djerban Erev Shabbos minhag of putting cholent pots into the communal oven. But apparently it wasn’t as easy as it sounded: as we put a pot in and then moved aside in order to let the hired Arab finish shoving it all the way into the oven, we were instructed to push it further in. This was clearly because, despite the fact that a Jew lit the fire, they did not rely on the leniency of the Rema and required, as per the Shulchan Aruch (see Yoreh Dei’ah 113:7), that a Jew put the food far enough in so that it would fully cook if left there.

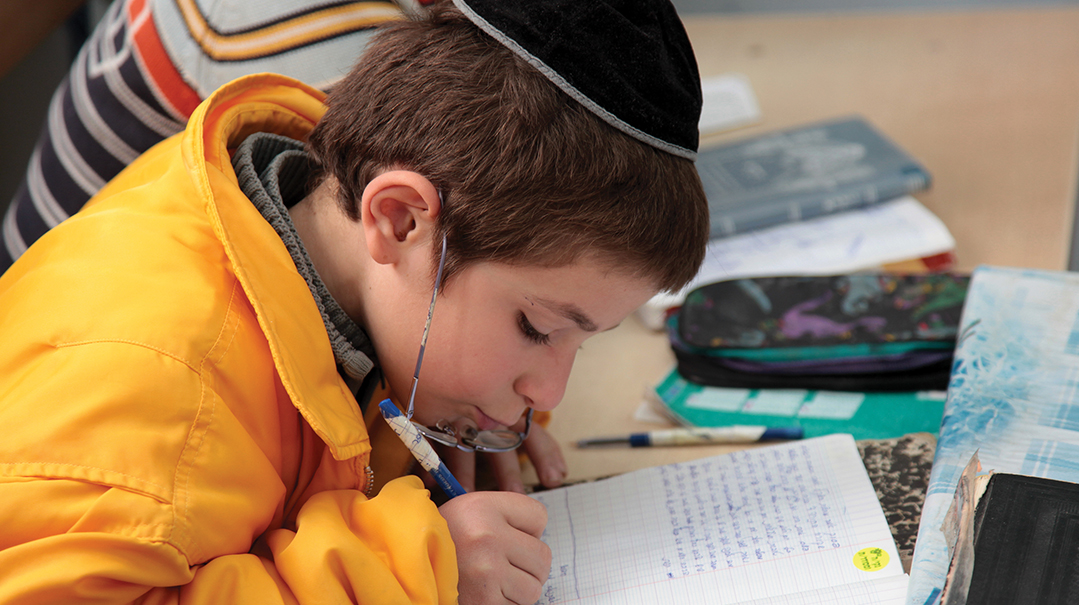

This halachic exactitude does not come from tradition alone. Every adult in Djerba speaks fluent Hebrew, and the chinuch is exceptional and truly impressive. We paid an extended visit to the yeshivah classroom of the 13 to 16 year olds, and were astonished by their knowledge, seriousness, and dedication to limud Torah. They proudly showed us a looseleaf with “teshuvos” that they had written on assorted topics.

Inside, Outside

Jews have lived among the Arab population of Djerba for centuries. They speak the language, look similar, and for the most part feel comfortable around the locals. But they are acutely aware that they are also outsiders. In 1948 the Jewish population of Tunisia was over 100,000. But following Tunisian independence in 1956, the government began a series of anti-Jewish actions, including abolishing the Jewish Community Council and destroying ancient shuls and cemeteries under the guise of “urban renewal.” During the 1967 Six Day War, rioters burned shuls and Jewish-owned stores, spurring many Jews to leave for France. Today, there are only 2,000 to 3,000 in all of Tunisia.

The overwhelming majority of the Jews today live in the Chara Kebira district. The island’s most famous shul, El Ghriba, is not there, but in the Chara Zrira area, whose Jewish population has dwindled to about five Jewish families. Nonetheless, one of the families there pays a few individuals from Chara Kebira to make the near-hour walk each Shabbos to ensure there is a minyan in the area.

Legend has it that a stone from the First Temple lies under the door to the El Ghriba sanctuary. Today El Ghriba has become a valuable tourist attraction, visited by Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike. In honor of Lag B’omer, hundreds come for the hilula — which turns the courtyard into a kind of carnival, with barbeques and singing.

We also had a good laugh on the taxi ride to El Ghriba. Ari G. was sitting in front and attempted to converse with the driver, searching for a common language. The cabbie knew no English and very limited French and Spanish, but then said that due to the large number of German tourists, his German was not bad. So, Ari G. shmoozed with this Muslim taxi driver in Tunisia in his broken Yiddish — which to the Arab driver sounded German enough.

The El Ghriba shul has seen its share of tragedy as well. On Simchas Torah in 1985, one of the Tunisian guards at the shul opened fire on the congregants, killing five people, including four Jews. On April 11, 2002, an Al Qaeda terrorist exploded a tanker filled with propane gas near the outer wall of the El Ghriba synagogue, killing 21 people — mostly German tourists. In November 2013, as Israel began Operation Pillar of Defense in Gaza, two shuls in the Tunisian town of Sfax were vandalized.

Follow-Up

Although they’re no longer the center of Jewish life, we wanted to see the area’s smaller shuls. In the mainland town of Zarzis, a 45 minute ride from the Jewish area on Djerba, the Mishkan Ya’akov shul, built around 1900, was seriously damaged in an arson attack by locals in 1982 following the Sabra and Shatila massacre of Muslim Palestinians by Christians in Lebanon. The structure and sifrei Torah were completely burnt, but the shul was eventually rebuilt and is today actively used by the town’s 100 Jews; there’s even an active cheder. Ben Zion, the rebbi for the older children, gave us a tour of the magnificent rebuilt shul. At one point, he surprised us by pointing out a secret exit hidden in the shul. In the event of an attack, the worshippers could climb through the door and sneak out through a hidden escape route.

Chaim, one of the leaders of the Zarzis community, told of how, during the anarchy of the 2011 Arab Spring revolution, the locals who live among and work with the Jews put up metal barricades to protect “their Jews” and their stores from the danger of marauding Muslims.

We discussed the security situation with many of the Jews we met. In Djerba the Jews recall the days of President Zine El Abidine Ben-Ali, the dictator who was the first casualty of the 2011 Arab revolution. While he was a dictator, he kept peace with a strong police force. The worst time for the Jews was during the transition when “the police disappeared.” The advent of democracy saw the return of police, but with the protocol that there would be no preventive arrests of provocateurs unless they actually committed a crime. Now after the current spate of terror attacks however, the government has restored to the police many of the preventive powers it had under Ben Ali, and the Jews have found this reassuring. While they profess to be perfectly safe and comfortable, there is still an undercurrent of fear that anything could happen.

Actually, we had another surprise in store when we discovered that there was quite an active police presence the entire time we were there, although your naïve humble writers were blissfully unaware of what was swirling around them. As we sat down for dinner on Friday night with our hosts, the teenage son asked us if we had been wandering the shuk earlier in the day. After we confirmed that we had, he asked us, “Do you realize that two plainclothes policemen were following you the entire time?” Embarrassed by our obliviousness, we asked him how he knew and he told us that he knows those two officers. It turns out that we had police watching us from the time we arrived. They did it for our protection.

Once aware of this, we saw police everywhere we looked for the next few days. At the entrance to the Jewish Quarter, there was a police van parked and officers with semiautomatic weapons standing guard. When we visited Zarzis, uniformed police quickly met us at the entrance to the shul, and again questioned us about our origins and intentions. The unnerving part was on our return to Djerba later that night, when the head of the community asked us with a smirk, “So, how was Zarzis?” When we asked how he knew where we’d been, he told us the Zarzis police had checked in with him regarding our presence. We could have felt like criminals, but instead we chose to feel protected.

Friends and Neighbors

The main street in Chara boasts several Jewish fast food places — but in Djerba, that term means a tiny one-room joint with a table or two. They usually serve brik, a delicious thin dough with a soft-boiled egg and potato in the center, either deep-fried or barbequed on coals out in the street. We saw numerous Muslim families in nice cars who drove in to the Jewish Quarter just to eat the food. No one here bats an eyelash when Muslims come from other parts of town to enjoy the delicacies in the brik store. But the trend is reciprocal. The old Jewish men go to the shuk nightly to play backgammon in a non-Jewish owned coffee shop. We too went out for coffee, in a segregated men’s coffee shop (the non-Jewish shops are often gender-separated). There we sat with about 100 Muslims packed into this kiosk, watching a soccer game on the big screen. We were speaking Hebrew and no one seemed to care — they’re used to the Jews and want them to feel safe. But we were in for a shock when we asked our friend Meir if the guys in the shop care about the 200,000 people killed in Syria. “Not at all,” he replied. What about the Palestinians killed by the Egyptians? “Nope,” he said. “But let Israel kill one terrorist and the entire climate becomes tense.”

Some things never change.

The Secret’s in the Dough

We’re always on the lookout for interesting or obscure Jewish rituals in far-flung communities, and one of our goals in traveling to Djerba, a resort island on the Tunisian coast, was to participate in the Jewish community’s “secret ceremony” on Rosh Chodesh Nissan. The details we’d heard of this “Bsisa” ritual were sketchy and we weren’t even sure we’d be granted entry, but we took our chances anyway.

The Bsisa always takes place on the evening of Rosh Chodesh Nissan and is usually celebrated with the extended family. Each family gathers together, usually in the home of the patriarch of the family, and locks the door so that no outsiders — even from within their own community — are welcome. We were fortunate that the nuclear family of Uziel Haddad agreed to separate from their extended family and include us for the ritual.

The evening begins with a large festive meal — this year it turned out to be the Friday night meal. After the seudah, the mother came out with a large bowl filled with ground grain and spices, whose aroma we were sure, like the incense of the Beis Hamikdash, was sensed all the way to Yericho. It was placed in front of the head of the household, and then the ritual began:

One by one, in age order, each family member stuck his pinky finger out over the bowl. The father liberally poured olive oil over the pinky such that it flowed into the flour mixture. Next, each participant lifted a key that was standing up in the mixture and stirred the mixture. When all of the family members were finished, Uziel looked at us as if waiting for us to take our turn. We joined in the fun and got our pinkies dirty and our hands covered with the batter as we picked up the key to give the final mixes. One more ingredient was then added: some gold jewelry that the father mixed in. Some families use designated gold coins. A short prayer was recited in Arabic and then each family member ate from the bowl. The texture and look reminded us of a brownie batter but the taste, well, we guess it must take some getting used to or a genetic predisposition to enjoy it. Some of the family seemed to really savor the flavor and they actually put aside some to keep eating the next morning and the rest of the week.

Few non-Tunisian Jews have ever participated in this ceremony, and we were left with two questions: What’s the meaning and origin of this practice? And wouldn’t the halachic prohibition of lishah (kneading) on Shabbos be of concern?

We felt awkward asking our host, but on Shabbos afternoon while strolling through the Jewish neighborhood we met up with the daughter of our friend and Djerban contact, a young married woman in her 20s. While men and women generally don’t converse in public, she told us that on Erev Shabbos the main topic of conversation among her friends was how to properly stir the bsisa so as not to violate the prohibition of “lishah”. It was concluded that the stirring should preferably be done in a crisscross rather than the usual circular manner, so as to introduce a shinui.

Later in the day, while talking to one of the local yeshivah teachers, we broached the topic and he told us that the subject had been discussed by a former chief rabbi of Djerba in his book of teshuvos, Zichrei Kahunah, (1965) in which he explained why it was permitted to stir the bsisa in a normal fashion on Friday nights. Indeed the rabbinic authorities of this ancient and learned community had dealt with the issue.

Regarding the first question, the source of the ritual is truly a mystery, although the key-dough combination initially reminded us of the shlissel challah traditionally made the Shabbos after Pesach. There are those who link it to the influx of Anusim to this ancient community 500 years ago. That would explain the secrecy of a ritual meant to announce the upcoming holiday of Pesach. Others explain that a similar type of ritual was performed whenever someone moved into a new house, and that this communal observance is in commemoration of the erection of the Mishkan on Rosh Chodesh Nissan. This would explain the use of the key and the Arabic prayer which includes a request for “He Who opens doors without keys” to grant us a good year and open doors for us. Yet others view it as a ceremony linked to the beginning of a new agricultural year, and the key, oil, and wheat are simanim meant to presage a year of prosperity.

There is another explanation that seems to fit this specific community. The Djerban kehillah was traditionally comprised entirely of Kohanim. The oil, the grain, and the pinky are all reminiscent of the kmitzah done on a korban minchah. Either way, we were thankful to the Haddad family for welcoming us — but it soon became clear that it was indeed a sacrifice on their part. Before we were fully out their door, they all scampered down the steps to the nearby grandparents’ house where they quickly joined their extended family of over 30 people.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 561)

Oops! We could not locate your form.