Between the Pale and St. Petersburg

| November 7, 2023The generous Gunzburgs supported a wide array of Jewish institutions, religious, social, and educational organizations

Title: Between the Pale and St. Petersburg

Location: St. Petersburg, Imperial Russia

Document: The Jewish Chronicle

Time: 1858

Whenever Baron Horace Gunzburg would travel out of the country to [what he termed] “chutz l’Aretz,” and again upon his return, he customarily would notify Rabbeinu Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor, the Kovno Rav, of his travel plans. The baron would set up an appointment to meet the rav in Kovno as he was passing through. They then would meet and travel together for several hours discussing urgent matters of public interest facing Russian Jewry.

During one of these meetings with the Kovno Rav, Baron Gunzburg presented the challenges then currently facing the Russian Jewish community and sought Rav Yitzchok Elchonon’s advice on various issues. He mentioned his grievances with the inaction and lack of initiative demonstrated by some of his tycoon friends in St. Petersburg.

“There’s a well-known saying — ‘The world stands on three pillars, money, money and money.’ I can’t personally fund every project through my own means. Despite it being beneath my dignity to personally request funds from others, I’d gladly forgo my own honor in order to advance the cause. The issue, however, is one of caution and danger. My actions in St. Petersburg are under close surveillance, and any false move or careless remark by someone else has the potential to jeopardize the entire venture as well as endanger both myself and my people.

“But you, Rabbi, can perhaps take it upon yourself to fundraise among the general Jewish population across Russia. Your actions aren’t under the same governmental scrutiny as mine, and everyone looks up to you as our holy leader. It would therefore be possible for you to undertake this initiative. A mass fundraising project would generate more funds than a thousand Gunzburgs could provide. I can’t carry the entire financial burden of Russian Jewry on my own.”

—Zichron Yaakov, the memoirs of Rav Yaakov Lifshitz, secretary to Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor of Kovno

While the rest of European Jewry reaped the benefits of emancipation over the course of the 19th century, Russian Jewry spoke of “selective integration.” A demographic explosion brought the Jewish population to well over five million, making Czarist Russia home to by far the world’s largest Jewish community. Imperial decrees forced 94% of those Jews to reside in a restricted area in the empire’s western provinces known as the Pale of Settlement, but a privileged 6% were permitted to settle in the Russian interior.

That privileged few included prominent merchants and financiers, university graduates, military veterans, and certain craftsmen. A large, wealthy, and acculturated community soon emerged in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg. It was led by an elite group of individuals who had amassed huge fortunes in banking, finance, mining, railroads, as well as the sugar, lumber, tea, and shipping industries.

Though some took advantage of the selective integration governmental policy afforded them and assimilated into Russian culture, others maintained close connections to their brethren back in the Pale of Settlement and emerged as a new cadre of leaders of Russian Jewry. Their vast wealth and physical presence in the capital afforded them a certain measure of influence with czarist ministers and government officials.

Perhaps no other family personified both the perceived ideal of selective integration and the true ideals of communal leadership and responsibility than the Gunzburgs. The patriarch was Baron Joseph (Yozel) Gunzburg, who began building the family fortune as a tax agent and then as a financier during the Crimean War. Following his move to St. Petersburg, he opened one of the most successful banks in all of Russia, often financing the debt of the czarist government.

At the same time, he served as the leading spokesman on behalf of the larger Jewish community, entreating various ministries to lighten the draconian anti-Jewish legislation in the realms of commerce, education, communal activity, religion, and the military draft. It was directly due to his and later his son’s influence that many such measures were rescinded or amended.

Upon his passing in 1878 while visiting Paris, his son Baron Horace Gunzburg succeeded him in both his commercial enterprises and community leadership and served as the self-appointed spokesman of Russian Jewry until his own passing in 1909. From far away St. Petersburg, he’d refer to the masses of the Pale as “my Jews” when discussing their plight with czarist officials.

Though many in the Pale regarded the St. Petersburg moguls with an often-justified suspicion that they were not correctly representing their interests, the Gunzburgs were generally well regarded and enjoyed popular support. The relative improvement in conditions for Russian Jewry during Czar Alexander II’s “great reforms” can be directly attributed to the involvement of the Gunzburgs.

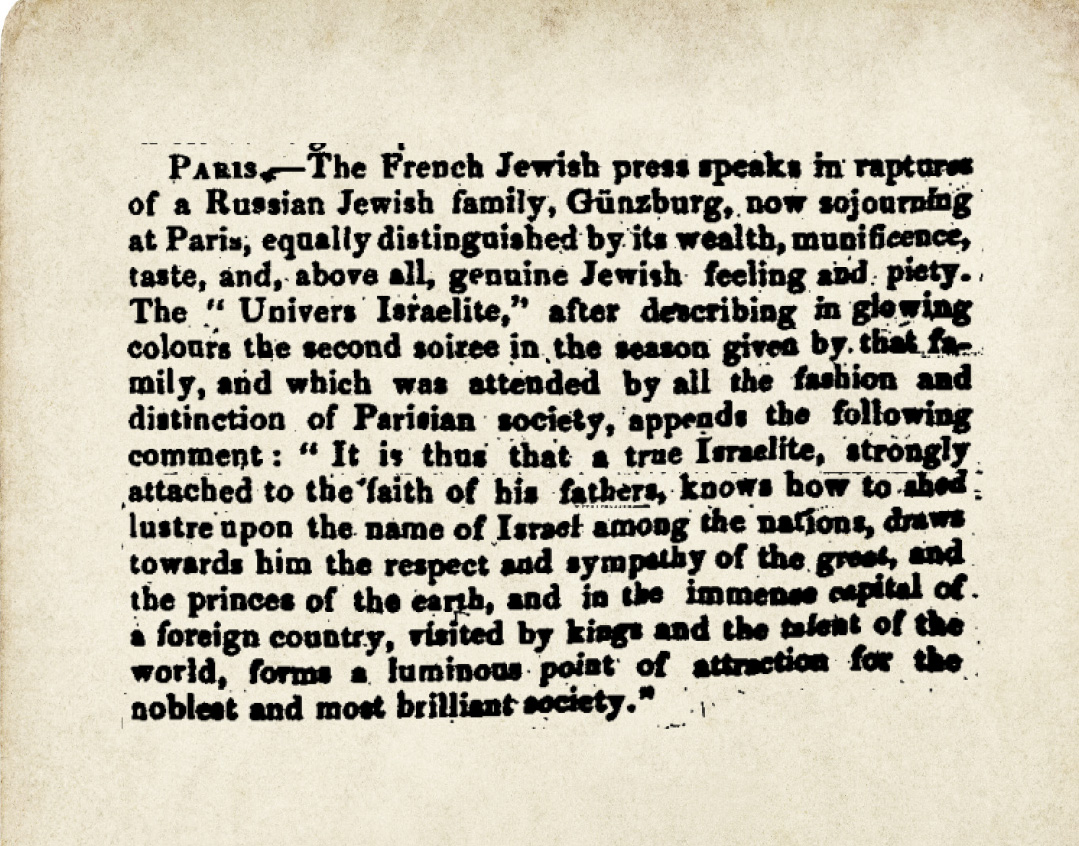

This was true in the realm of philanthropy as well. The generous Gunzburgs supported a wide array of Jewish institutions, religious, social, and educational organizations, with many endeavors across the Jewish spectrum benefiting from their largesse.

The Synagogue That Still Stands

In 1870, St. Petersburg still lacked a proper synagogue. This changed when Czar Alexander II approved the construction of the Grand Choral Synagogue in 1869, prompted by a request from Joseph Gunzburg. Joseph’s son Horace oversaw the construction during his tenure as leader of the Jewish community from 1869 to 1909.

The land for the synagogue was purchased in 1879, but the construction hinged on various conditions. These included distance requirements from churches and government roads, and a height restriction of 23 meters, the height of the czar’s Winter Palace. Exemptions were only given for bell towers and domes because they also served as observation towers for fire watch and other safety purposes. In a nod to his kinship with the Jewish community, the czar gave his approval for a building that topped out at 47 meters. The Choral Synagogue is still operational nearly a century and a half later.

Navigating the Storms of the Negev

With the outbreak of the pogroms of 1881 (known as the “storms of the Negev”), Baron Horace Gunzburg hosted a meeting of Jewish leadership from across Russia to confront the challenges of anti-Semitism and present a unified front to the czarist authorities. A primary guest was Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor of Kovno, accompanied by his son Rav Tzvi Hirsh. Gunzburg invited Rav Yitzchok Elchonon back for a follow-up meeting a year later that also touched on the new waves of emigration from Russia. Yaakov Lifshitz notes that the baron also included “additional great rabbis and communal activists, including Rav Elya Kretinger, Rav Zev Cohen of Vitebsk, Rav Beinush Katznellenbogen of Kiev, and other gedolei Yisrael.”

Tea and Sugar Tycoons

Kalman Wissotzky made his fortune in the tea industry. Though he managed his business interests in his Moscow residence, far from the Pale, he remained an observant Jew throughout his life. In his youth he studied in the Volozhin Yeshivah, and he was also a talmid of Rav Yisrael Salanter. The famed Brodsky Kollel for young married Torah scholars that was affiliated with the Volozhin Yeshivah was endowed and funded by the sugar magnates of Kiev, Yisrael, and later his son Lazar Brodsky.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 985)

Oops! We could not locate your form.