Behind the Wall

| October 25, 2022Their home felt warm, magnetic...menacing

IT begins with Duvy, of all people. The Krasner family had moved into their new house almost six months ago, a run-down house in a corner of Brooklyn, which had needed extensive renovating, and Duvy had decided that it was haunted.

Not that the Krasners really believe in haunting or ghosts, but there’s something undeniably odd about the house. A strange rattling in the sink drain had revealed an old necklace. A loose floorboard pried up by the three-year-old had exposed a photo beneath it. Under one radiator, Chavi had accidentally vacuumed up a small ring. The house still seems to carry the presence of a former owner, and eight-year-old Duvy feels they’ve never left.

It’s only natural, then, that when he notices spots appearing on the back of his closet, he doesn’t think anything of it. Strange things are always happening in the Krasner house, and this is just the ghost asserting itself. The spots begin to grow, and Duvy ignores them in the way that he ignores everything about his closet, except the pants that he’d knocked to the floor earlier that week and needs for school.

The spots become larger, meet and bloat, until Mrs. Krasner is putting away laundry one afternoon and parts the sea of grays and browns and greens in the closet. She shrieks, and everyone runs. “It’s the ghost!” Duvy announces, waving dramatically at the wall.

“Oh, it’s much worse than that,” Mrs. Krasner says mournfully. “It’s mold.”

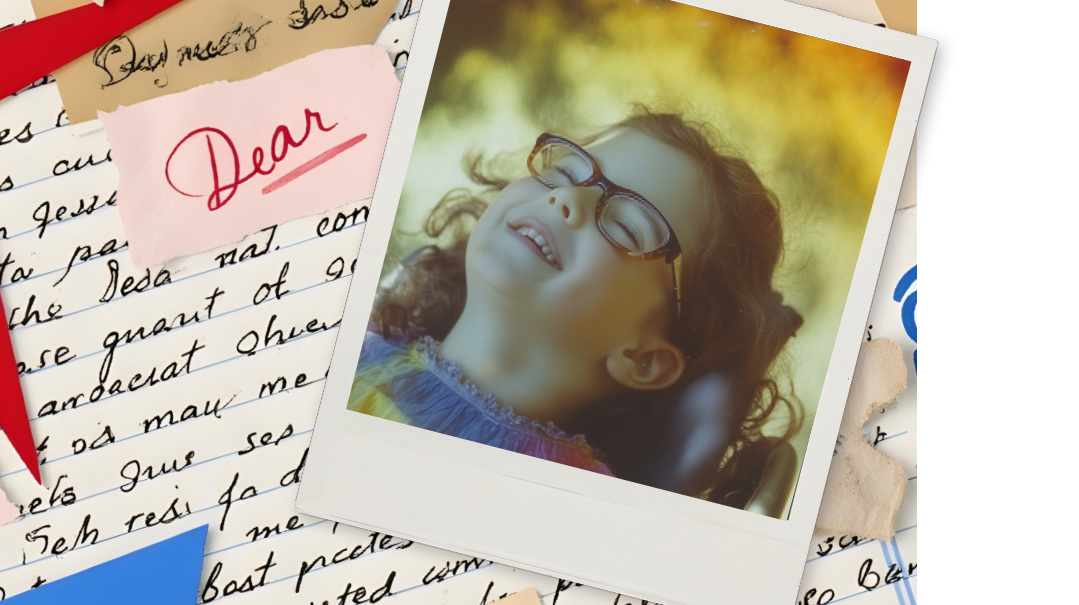

Ayesha Franklin is accustomed to being a fish out of water. She’s always been a little strange, a little too bright, and a little too caustic, but that, she feels, has proven an advantage. Maybe it’s why she’s always challenged herself, has always pushed to flout expectations and to take every obstacle as an invitation.

It might explain why she’s become the rare woman in the mold-removal business. Or why she’s come back to Brooklyn after 30 years away, seeking some thread that she’s never been able to weave into her life. Her grandmother had grown up here, somewhere in a little postwar enclave that Ayesha only vaguely remembers when the bus passes it, and her heart had cried out without knowing what it was seeking.

Her grandmother — “Bubbe,” she’d called herself, though her real name had been Fruma, and Ayesha had gotten strange looks in childhood when she’d referred to her — had lived in her house with an aide even when she’d been in her nineties and had refused to move to the nursing home where Ayesha’s mother had wanted to send her.

Ayesha and her mother had gone to visit her once a week, taking the Q train across the city to venture into that old, musty house. She remembers Bubbe with her light-skinned face and toothless smile just for Ayesha, the way she’d light up and wheel herself to the door when they’d arrive. Bubbe would pluck a candy from somewhere inside the couch and Ayesha would lay it on her tongue and let the sugar seep into her taste buds.

Bubbe would say, I used to love those in the alte heim, with a wistful sort of smile. She’d drop phrases like that sometimes; inevitably, they made Ayesha’s mother grimace. Bubbe liked to talk about the first ten years of her life, before the war, though she rarely discussed the years of the war. Only once that Ayesha can remember. There was nothing after they came. Not food, not clothes, not faith.

Six-year-old Ayesha hadn’t questioned that. Her grandfather, a staunch Protestant, had put up a Christmas tree, and her mother had followed suit. Ayesha had grown up without considering her roots, and it hadn’t been until her mother’s death a few years ago that she’d begun to second-guess it all. Is this what it is, two generations after trauma, to find yourself rootless? Is this all she is now, a woman descended from slavery and concentration camps, a girl with a history that has all but been erased?

Oops! We could not locate your form.