Behind the Iran Curtain

| June 24, 2025Fear, futility, and the high price of protest

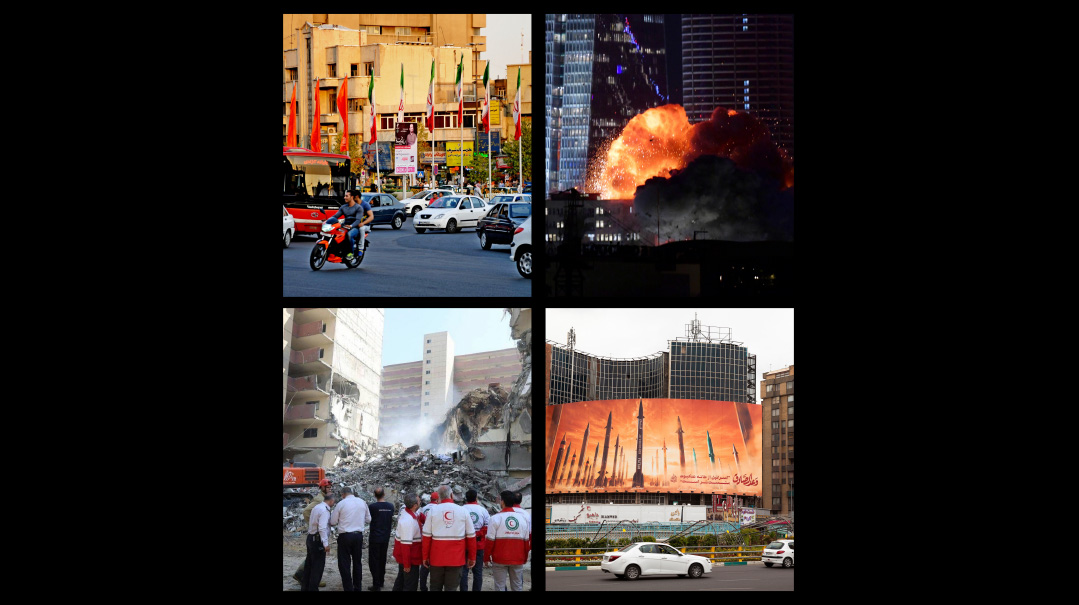

Photos: AP Images

The civilized world may finally be starting to catch on that the Islamic Republic of Iran is every bit as evil and oppressive as the other regimes that have come after the Jews down through the millennia.

But we are cautioned that, unlike Pharaoh, Titus, and Hitler did, the mullahs in Tehran do not enjoy the support of their populace in their obsession to destroy the State of Israel. If anything, we are told, the leaders are more frightened of their people than they are of the Jews. And the Iranian people, we are told, hate their rulers far more than they hate us.

Is that true? If so, where is the popular uprising to overthrow the ayatollahs? And if there were one, who would take over?

It is notoriously difficult to get accurate information out of the Shia dictatorship, and even more so in wartime. I made the rounds in Washington, D.C., of various Iranian expat organizations opposed to the mullahs to try to get a read on the situation. They can hardly be described as impartial observers — many of them, or their parents, had to flee Iran because they resisted the regime’s rule. Also, some of them have been out of immediate touch with local sentiment in Iran for years — even decades.

But they do bring an intimate understanding of the depths of cruelty exerted by the heirs of Ruhollah Khomeini, an understanding that can help shed light on our present predicament. It all amounts to a terror campaign conducted by the Islamic Republic against its own population: brutal internal security forces, communications blackouts, economic disruptions, and fingering scapegoats.

And the one name that keeps coming up, in discussions of a provisional government to replace the mullahs, has a familiar ring: Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, the son and heir apparent to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah ousted by the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Besieged by Basij

Reports out of Tehran right now describe a city on edge. During the periods between visits by the Israeli Air Force, the streets are eerily quiet — but not calm. Security forces roll in armored convoys. A government-imposed weeklong Internet blackout has slashed connectivity by over 97 percent since June 17. Behind locked windows, Iranians wait. Not in defiance, but in dread.

“We’re already hearing reports of mass presence of security forces on the streets of Tehran,” says Andrew Ghalili, a senior policy official at the National Union for Democracy in Iran, or NUFDI, a Washington-based nonprofit representing the Iranian-American community.

This isn’t the first time the regime appears vulnerable, and memories of the past remain seared into the Iranian psyche. In 1988, thousands vanished in secret executions. In 2009, protests over fraudulent election results triggered the “Green movement,” which seemed on the verge of toppling the regime — until security forces ruthlessly crushed it. In 2019, protests over fuel price increases spread like wildfire, triggering another regime response that killed nearly 1,500. In 2022, more than 550 perished in the Mahsa Amini protests, so named for a young woman arrested for not wearing a hijab who died in custody.

When the regime in Tehran feels cornered, it doesn’t hesitate to unleash one of its most loyal weapons.

The Basij — short for Basij-e Mostaz’afin, or “Mobilization of the Oppressed” — is anything but oppressed. Formed in 1979 at the behest of Ayatollah Khomeini, this volunteer militia answers directly to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and has become the regime’s go-to enforcers. Think of them as ideological foot soldiers, equal parts morality police and equal part protest suppressors.

Estimates of the size of Basij forces vary widely. The head of the Basij claims more than 23 million members, but other sources put the number of actual armed troops at something like 50,000. The forces are recruited from most heavily Shia sectors of the population. But when the people get especially restive, and the IRGC wants to respond with live fire, it supplements Basij units with imported terrorists — Hezbollah, Hamas, and extremists drawn from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, none of whom feel pangs of conscience when gunning down Iranians.

Over the years, they’ve built a reputation for showing up fast and hitting hard. Whether it’s breaking up student demonstrations or chasing down violators of their modesty laws, these militia march in on motorcycles to thump truncheons, blast bullets, and foment fear. The Basij don’t just maintain order, they enforce loyalty. And in moments of national crisis, they’re often the first to flood the streets. Not to protect the people, but to protect the regime from the people.

The Basij militia began appearing prominently in the streets more than a week ago, as Israel intensified airstrikes on regime targets. Internal security responded by mobilizing Basij units across urban areas as well as in provinces with heavy minority population centers, for widespread patrols, establishing checkpoints, and the rounding up of thousands of civilians who’ve garnered regime attention in the past.

Communications Blackout

And this is one possible reason why, despite shockwaves from Israeli airstrikes and skyrocketing dissatisfaction, popular protests remain limited. But another reason may be equally important: a communications blackout. Cutting off the Internet does more than just leave people in the dark; it also prevents any potential uprising organizers from connecting and coordinating. That’s exactly how the mullahs want it.

“We’re not getting pictures and videos of it because the Internet is out and people are scared to take pictures, but this is [the regime’s] playbook,” says NUFDI’s Andrew Ghalili. “They cut off the Internet, and if people start protesting, they kill them.”

One possible positive sign from the Internet blackout is that it shows how vulnerable the regime is currently feeling.

“The last time they did it,” says Khosro Isfahani, a senior analyst for NUFDI, “it was in 2019, and they killed 1,500 people. So, that means they’re desperate. A total Internet shutdown is their last move.”

Despite the regime’s attempts to wall off the country from the outside, there are always leaks. Arash Farhadi is a human rights investigator who managed to flee Iran in 2021. When he was working as a reporter for a local financial newspaper in Iran in 2019, he began covering the eruption of anti-regime protests. But he quickly discovered that no Iranian outlet was willing to publish honest reporting about what was happening on the streets. The government’s red lines weren’t just firm, they were fatal.

Shut out by domestic media, Farhadi began collaborating with international human rights groups. He soon connected with a London-based organization focused on freedom of expression, and over the next three years, he became a critical source for leaks from inside the Iranian regime.

“You’re gambling with your life,” Farhadi says. “And the leaks that I was getting involved a lot of personal sacrifice.”

One such leak came from deep inside a fortified IRGC base during a state-sponsored satellite launch:

“I was working the tech and industry beat, so I wiggled my way into covering the launch. It was in Semnan, a secure military site. I used someone else’s credentials, literally wiped their name off the press card with spit, and got in. I got out, reported on it, then passed more of the information to the right people.”

Farhadi’s work eventually helped expose regime propaganda, internal corruption, and censorship systems from within. But each story came with risk, and each leak, a cost. “One of the things that I did during that period was putting together a report for the ADL on how anti-Semitism is embedded into education system in Iran, I was gathering the school books for them and pointing out the fun parts.”

Saving Themselves

There are no fun parts for the Iranian people in their current troubles, however. The presence of the Basij and the communications blackout are only the beginning. The leaders are fighting a war against the State of Israel, but are taking action only to shelter and protect themselves, and no action whatsoever to shield their people from the collateral damage, or from the economic fallout.

“People are scared,” says Khosro Isfahani, “I mean, it’s terrifying. And we are dealing with a regime that has zero infrastructure for protecting the people, there is absolutely nothing there. There are no shelters, there is no warning when there a strike is happening.”

The economic disruptions that inevitably result only end up serving the short-term interests of the rulers.

“Food shortages are already hitting the country,” Isfahani says. “Prices of staples are skyrocketing. One example, the cost of a pack of cigarettes has not just doubled or tripled — it’s increased tenfold since yesterday. People are struggling to just get by.

“At the same time, fuel distribution has been disrupted. Banks are not giving people money. One bank was hit in a cyberattack yesterday. But the wider issue with banking is the incompetence of the regime. The ATMs are down because they cannot put cash back in the system.”

While a collapsing system may seem like a place ripe for a rebellion, try launching one on an empty stomach.

“You’re watching a whole system crumbling, and it’s not just because Israel is targeting military assets, it’s because the government in Iran is inherently corrupt and has zero care for human life,” Isfahani declares. “They have given up on governing the country and are only focused on saving their own lives, and mounting these attacks against Israel at the same time.”

Scapegoats Wanted, Apply Within

For a regime wanting to deflect blame for the disaster afflicting its people, Israel and the Jews provide a reliable scapegoat. But the usual suspects, Iran’s trapped, beleaguered Jewish community, is small – between 9,000 and 15,000 — and the rest of the population offers many other options. Ethnic Persians, interestingly, comprise only some 61% of the total; the rest are Azeri (16%), Kurdish (10%), and assorted other minorities.

In that last category, one group in particular stands out: the Balochi people, who reside in southeastern Iran. They have often clamored for greater autonomy, and have ethnic cousins on the other side of the border with Pakistan. This makes them a convenient regime target, says Arash Farhadi.

“We’re talking about millions of people in Balochistan with no drinking water,” he says. “During the summer, they gather water from shallow ponds, using plastic buckets. Every year, children drown in those ponds. It’s poverty, it’s neglect, and it’s systemic.”

And now, he warns, that same neglected population is being cast as the regime’s next scapegoat. “They have no power, no political agency. And that makes them easy targets.

“If this regime survives,” Farhadi cautions, “it’s going to be a bloodbath for any dissenting voices, with ethnic minorities being the primary target. After the Islamic Republic came to power, the first thing they did was shelling the Kurdish city of Sanandaj, because they were interested in a role in the future government. They wanted their voices to be heard, they wanted a level of autonomy, and the regime dispatched armed forces and shelled them.

Rahim Rashidi was born in the Kurdish region of Iran, in the town of Saqqaz, a year before the revolution that toppled the Shah. He became involved in anti-regime activities from a young age. At just 16 years old, he joined the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) and began working at their radio station, broadcasting anti-regime messages into Iran from Iraqi Kurdistan. His early work focused on journalism and activism, rather than direct combat, although he was deeply embedded in the Peshmerga resistance movement. His family had suffered under the Iranian regime, his father and brother were imprisoned “many times, for political reasons.” Mounting pressure forced him to flee Iran in 1996.

“Saqqaz had a large Jewish population before 1979,” Rashidi says. “In our culture, when someone is super smart, we call them ‘Jewish.’ When someone is super rich, we call them ‘Jewish.’ Being Jewish was seen as a positive thing.”

Rashidi says he talks to contacts in Iran every day, and he says people are upset that the US isn’t actively pushing for regime change. “The Kurds are ready, but it’s not enough. The Balochis are ready, but it’s not enough. If the protests started from the big cities — Tabriz, Tehran, Isfahan — we’d have a revolution. The regime would be forced to move troops from other parts of Iran to save capital city and then there would be space for us and for others to come out. But nothing happened and we paid a big price.”

Will the Enemy Within Please Rise?

Could the tables finally be turning against the mullahs? For decades, the Iranian regime has relied on a familiar script: Blame the United States and Israel (or the Balochis, or the Kurds) for everything. But a substantial segment of the Iranian population isn’t buying it. The question is how big, and for how much longer.

“A campaign was launched a couple of days ago, with people tweeting under the hashtag ‘Our enemy is here,’ ” says Khosro Isfahani of NUFDI. “They’re saying: Stop lying to us that the enemy is America or Israel. The enemy is the Islamic Republic.”

This sentiment isn’t coming from fringe groups or exiles, it’s being voiced by families who’ve suffered under the regime’s brutality. “People who lost loved ones during protests, who were arrested, tortured, killed, or maimed, are now speaking out,” Isfahani adds. “And they’re saying plainly: Israel is not our enemy.”

That message is resonating across demographics.

“One of these families that had been very vocal about Israel not being the Iranian people’s enemy, their home got raided by security forces, they broke the door, went in, and were trying to arrest the family in front of their young children,” says Isfahani. “Members of this family got themselves to the balcony, and they were shouting while security forces were in their home, ‘Israel is not our enemy, the Islamic Republic is.’ That was one of their lines, and the other one was, ‘Your time is up, the Islamic Republic has got to go.’ People are seeing this as an absolute frustration with the regime that has occupied the country for decades, suffocated.”

What happened to the family? I ask Khosro Isfahani.

“Apparently, they weren’t taken into custody, because a large crowd was gathering,” he replies. “But arrests are happening. People are being targeted and taken in for interrogation.”

Iranian public opinion, while not exactly pro-Israel, seems at least not inclined to be hostile.

“In general,” says Isfahani, “the sentiment in Iran, regardless of your politics, doesn’t see Israel as an enemy. Bibi Netanyahu even has a nickname, they call him ‘The Middle East Chef,’ because commanders who get killed are called ‘cutlets.’ So Bibi is the chef. We are not cheering the war. We are cheering the killing of those who butchered our children. That’s a general sentiment, from friends, family, people of all backgrounds. There’s jubilation when these people are taken out.”

Man of the People

But the regime is trying to smother that sentiment and rewrite the script. As the Islamic Republic scrambles to contain its latest legitimacy crisis, Iran’s Supreme Leader is suddenly speaking like a man of the people. Not to the people, but about them. Why, though?

“The way Khamenei has been talking for the last few days,” notes Andrew Ghalili, “he’s trying to create this nationalistic, rally-around-the-flag effect. Saying Israelis are killing the Iranian people. He’s never mentioned the Iranian people like this before in his life.”

The message? Blame the Jews. Wrap yourself in the flag. Hope nobody notices the regime is on life support. But behind the curtain, something bigger is brewing: the line of succession for Khamenei’s throne. And it’s not going well.

“Even before this war started, there was going to be a succession crisis,” Ghalili explains. “[Assassinated president Ebrahim] Raisi might have been the guy to take over before he died. There was a conspiracy that the regime killed him so that Khamenei could put his son Mojtaba in place. But if his son takes over, now you have the nepotism idea. They overthrew a monarchy for putting the son in charge, and now they’re doing the same thing.”

That’s not a smooth transition. That’s déjà vu with a turban.

And in that power vacuum, one name keeps surfacing. Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, the eldest son of the Shah, who was deposed in the 1979 revolution that brought the ayatollahs to power.

“What the Crown Prince has always said is, ‘I’m ready to take a leadership role of the transition,’ ” Ghalili explains. “He’s never, to my knowledge, suggested that he wants to be a king. What he’s always said is he wants to help create that environment where everyone is able to participate in the political sphere.

Not long before press time, Pahlavi announced at a press conference that he was creating a mechanism for security officials in the current regime to contact him and arrange to join his “revolution.”

“Israel is not going to overthrow the regime,” says Ghalili. “It’s going to be the Iranian people. That doesn’t happen without security forces, at least in some fashion, defecting. We at NUFDI have been pushing for a long time the need for the US, Israel and others, to encourage defections from within the security forces. That’s the only way.”

In other words, no regime change package can be brought in from the outside. No boots on the ground. No coronation ceremony. Just the people, a vision and hopefully a little help nudging key pieces off the board. But that doesn’t mean Israel shouldn’t tread carefully.

“As much as this is Ali Khamenei’s fault, this war,” he warns, “every Israeli strike that kills an Iranian civilian has the potential to hurt morale among Iranians. As few Iranians dying as possible is helpful.”

Because at some point, too much blood can poison even a righteous cause. And yet, the cause persists. Just ask Khosro Isfahani, a veteran dissident who’s fought the regime with facts, files and firewalls.

“For me, it has always been a single fight,” he says. “It’s a fight against the Islamic Republic. I don’t care who is willing to stand by my side in this fight, I don’t care about the format of the government, I don’t care who is going to be the transition leader. I’m a soldier in the trenches. Whoever gives me the ammunition to fight this regime, I would thank them and keep fighting.”

Still, even foot soldiers need a blueprint. And for that, Isfahani turns to the Jews.

“The same way the people of Israel had principles — the moment they were establishing their state—on who to get aid from and how to hold the ground… I’ve been telling everyone at this office to go and read A State at Any Cost, Ben Gurion’s story. We have a lot to learn from our Jewish brethren.”

Potential of the regime’s slow-motion implosion is fueling new conversations about Pahlavi’s role.

“What I’m hearing from many people who are not monarchists… many of them are seeing Shahzadeh Reza Pahlavi as a force that can lead the transition,” Isfahani says. “Even if Iran is going to become a monarchy again, they see him as a force for good.”

Does that mean a return to the crown?

“I’m assuming millions of people would want that system. A large portion of society have nostalgia for the Shah’s era, it was a better era in many senses. Iran was prospering, it was growing, it was moving forward.”

But beyond the nostalgia is a man with a clean record and a calm demeanor.

“He has been polite, kind, caring toward the nation,” Isfahani adds. “There’s not much dirt against him. He hasn’t done anything problematic that would make people hate him as a leader or sovereign.”

And though it’s been decades since Pahlavi last stepped foot in Iran, the connection hasn’t faded.

“He has deep connections, deep roots, in that culture,” Isfahani points out. “So I think a large portion of the Iranian people would rally around him the moment they have a chance.”

The Missing Link

America is taking steps to help a potential uprising gather steam. One of the regime’s most reliable weapons against protest is its kill switch on the Internet. In a country where online communication is often the only lifeline, that blackout can be suffocating.

Enter the Maximum Support Act, Washington’s boldest legislative attempt yet to pierce the regime’s digital iron curtain. Drafted by NUFDI with input from dissident groups and policy thinkers, the act does more than just talk tough on Tehran. It gets technical, it gets tactical, and most importantly, it gets above the cables.

“We introduced the Maximum Support Act a couple months ago that had a big section on Internet access,” explains Andrew Ghalili. “One of the things that we asked for was direct-to-cell Internet. Anyone with an iPhone 14, 15, or 16, or certain Galaxy and Samsung phones, as long as they can see the sky, you can connect satellite Internet and it allows you to send text messages.”

It’s called satellite-to-cell connectivity, meaning, your phone doesn’t need to talk to a cell tower. It talks to space. The plan is to make sure Iranian civilians can still get messages out and information in, even when the regime yanks the plug.

“The Internet blackout is severe,” says Andrew Ghalili. “We are hearing much less from the ground. Everyone is hearing much less from the ground. Inside Iran, people can’t reach their parents. We get moments of blackouts, and then someone can check in quickly, but this is what we’re facing now. And it’s why we’ve been pushing for so long for the US to create infrastructure to get VPNs and Starlink into Iran.”

That’s where Starlink comes in. Developed by SpaceX, the satellite-based system gained traction in 2022 during the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising, when Elon Musk offered to provide free access to Iranian dissidents. Unlike traditional networks, Starlink bypasses government-controlled infrastructure entirely. It connects users directly to satellites in orbit, no regime approval required.

“When Elon Musk sent the Starlink, I helped send 400, 500 devices, to people inside Iran,” said Kurdish journalist Rahim Rashidi. While 400 to 500 units might seem like a drop in the bucket for a country of over 88 million, Rahim said it “helped a lot but only for a small area.”

Each user needs a Starlink terminal, a small dish that comes with a router and power supply. Once set up, the dish automatically aligns with passing satellites overhead and beams data directly to them. These satellites then relay the signal to ground stations and back, enabling high-speed Internet access almost anywhere on Earth.

Even when devices are successfully delivered, they can’t always be used openly. Their GPS signals risk giving away user locations. That risk is often too great for civilians already under surveillance.

“There’s an effort now to actually like smuggle Starlink devices into Iran,” says Ghalili. “That gives people much more unfettered Internet access. The issue with that is twofold. One, smuggling it in is obviously difficult. Two, it’s traceable. The regime can track and figure out where that Starlink device is.”

In a country where surveillance is constant and retaliation is brutal, even a few minutes of online freedom can come at a steep cost. But for many, the risk is worth it.

In moments of national crisis, information is everything, especially under a regime that survives on secrecy and fear. Starlink showed Iranians a glimpse of what digital freedom could look like, but without scaled deployment and stronger protections, that light in the sky risks remaining just a flicker.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1067)

Oops! We could not locate your form.